Do Not Delete 9/28/2010 3:43 PM Do Not Delete 9/28/2010 3:43 PM

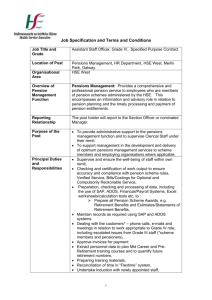

advertisement