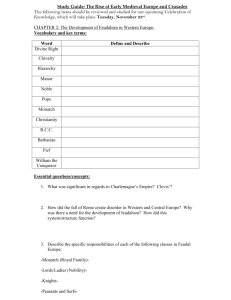

Obama and the Crusaders

advertisement

Obama and the Crusaders By Adam Gopnik February 13, 2015 The New Yorker “History simplifies,” wrote the great baseball analyst Bill James, thirty years ago. “But you never know in which way.” He was writing, as it happens, about the career of Dave Parker, the great Pittsburgh Pirates outfielder who seemed a lock for the Hall of Fame until the cocaine scandals of the early eighties got him by the throat, or, rather, by the nose. Would history recall the drugs and keep him at a distance, or would it forget them and see only his sterling record? The Hall of Fame hasn’t opened to him yet. But James’s rule is true of bigger histories, too: history does simplify—the trick, a hard one, is that restoring complexity doesn’t always make things clearer. This reflection is set off by something the President said recently, at the National Prayer Breakfast, apropos the horrors of ISIS’s murder of helpless captives. His comment was seemingly obvious and unobjectionable: that almost every religion (perhaps excepting certain strains of Buddhism, Jainism, or the like) has been implicated in horrors throughout its history, including his own Christian faith. “During the Crusades and the Inquisition, people committed terrible deeds in the name of Christ,” he said, stating a truth that one would think only the half crazy could dispute. Well, half crazy is not so hard to find in America, and Obama’s statement became a source of outrage among the predictable parties, with a lot of frantic Googling to find evidence that our record, though it may look bad, is nowhere near as bad as theirs. The Crusades were not that simple. They were reprisals for Muslim invasions. (This is the “Ma, he started it!” school of moral inquiry.) They weren’t even called the Crusades! (But then the Holocaust was never called the Holocaust while it was happening.) The Inquisition? Well, the Inquisition didn’t actually burn people alive; it told the state authorities that the heretics were hopeless, and they did the burning. (So that’s all right, then, said all the heretics burned alive.) And, anyway, everybody burned and massacred everybody back then. This leads, in turn, to a fixed line of apologetics, which the ideologically minded for some reason think particularly profound: it wasn’t the faith itself, just some misfits among the faithful, who did the killing. That the terrorists in Paris cried out “The Prophet is avenged!” doesn’t implicate their religion anymore than that the Catholic Church’s participation in those autos-da-fé implicates the Church. History does simplify, and even horrors have micro-histories of their own. This accounts, perhaps, for a primitive but common confusion between the forces that make history and the facts that history makes happen. The forces in history are always multiple, complex, and contingent, much more so than the fables make it seem. The forces in any particular historical event are always almost infinitely divisible into smaller and often contradictory parts, with a lot of fuzzy cases and leg room. The Crusades were a lot more complicated than an assault of murderous Christians on innocent Saracens. But the basic facts remain the same: huge numbers of helpless people, from Jews in Central Europe to Byzantine Greeks in Constantinople, got raped and tortured and murdered in the name of faith. You don’t have to be Jewish to enjoy Levy’s rye bread, the old ad used to say, and you don’t have to be Jewish to deplore the massacre at Worms. The Crusades were not an assault of evil Christians on innocent Muslims anymore than the Turks who took Byzantium were horrible savages engaged in a war with classical humanism. But what happened happened. We welcome complexity because it makes the moral points stand out more clearly against their background, just as we welcome linear perspective in paintings because it makes the acts of the foreground figures more fully articulate. We can understand the long pasts that make bad things happen and still put the blame on the bad people who did them. Ideologies are abstract; the acts they inspire are real. You can immunize any ideology, no matter how vile, if you insist that no one is responsible for what it actually creates. You can give any doctrine in history tenure if you insist that it’s responsible only for the good things that came of it and ascribe the rest to misunderstandings and mistakes. There are people who will say that Stalinists or the Khmer Rouge, not Marxists, staffed the Gulag or the killing fields; that rogue elements of the American army, not Americans, massacred the Vietnamese at My Lai; and so on. But no doctrine or national ideal exists pristinely, outside the practices of its believers. (Nazi apologetics has trafficked in exactly the same apologias—the Bolsheviks started it—but on the whole the memory of Nazi horrors is sufficient to get this line of argument shut down.) The job of the good historian is to balance understanding with indictment; it’s the polemicist who tries to use history only to plead innocent. The acts of the Crusades, like the facts of slavery, happened. Fanatics acting in the name of a faith murdered thousands of helpless people. That nobody else did better in the period of the Crusades is not the point; it is exactly the problem. It’s why we feel now that all the fanaticisms and ideologies at large in the period were equally horrible, and why we thank our stars, and our enlightened forefathers and foremothers, that we have (mostly) escaped from them. Bad acts may rise from good causes: faith may never be the enemy; fanaticism is always the enemy. But faith has always been the first seedbed of fanaticism. That’s why, when people commit acts of horrible cruelty for political purposes, we say that they’ve made a “religion” out of their politics, or have succumbed to a mad ideological dogma. Fanaticism is the belief that a single faith or ideology contains all the truth of the world, and that others should at best be tolerated. Liberalism is the belief that toleration is not enough, that an active, affirmative pluralism is essential to social sanity. Pluralism is the essence of liberalism—including the possibility of self-reproach for things that liberalism has done badly. America is not responsible for My Lai only to the degree that America renounces the self-righteous “exceptionalism” that put those murders in motion and then prevented those who caused them from being blamed. Excessive scruples—liberal guilt—are as sure a sign of sanity as excessive sanctimony is a sign of the opposite. It became clear, as the week went past, that one needn’t go so far back to find ISIS-style deeds committed by Jesus-styled people. (Ta-Nehisi Coates and Jamelle Bouie have pointed out that horrors precisely congruent to those carried out by ISIS were pursued by lynch mobs in the American South with implicit evangelical approval, and at times active endorsement, in our own recent history.) The President’s point turned out to be not just exactly right but profoundly right: no group holds the historical moral high ground, and no one ever will. But this is not because a moral high ground doesn’t exist. It’s because we’re all still climbing.