rhetorical analysis

advertisement

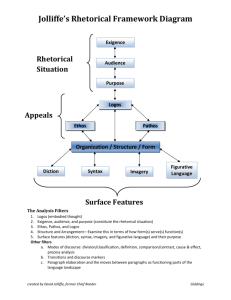

RHETORICAL ANALYSIS WHAT IS RHETORIC? • Rhetoric is: • The faculty (Aristotle calls it a dynamos—an improvable art) • of finding (not necessarily using, but certainly finding) • all the available means (everything a writer, speaker, or artist might do with language or images) • of persuasion (writers, speakers, and artists aim to shape people’s thoughts and actions) • in a particular case (rhetoric capitalizes on the particular) • to achieve meaning, purpose, and effect • In other words, Aristotle says that rhetoric is a teachable art and that people can get better at it. To Aristotle, rhetoric was dominated by invention, for which he used the Greek noun heuresis, or “a finding.” The English cognate noun, heuristic, means “a systematic process of finding and solving problems.” Since rhetors (writers and speakers) operate in specific situations, cases which embody exigence (requiring immediate attention; need), audience (people either immediate or mediated over time and place, capable of responding to this exigence), and intention or purpose (what the writer or speaker hopes the audience will do with the material presented: make meaning, realize its purpose, recognize its effect), rhetorical analysts ought to be able to determine, by drawing inferences, the exigence, the primary and secondary audiences, and the intention or purpose of any text they analyze. Logos, Pathos, Ethos • The “Artistic Proofs”: logos, ethos, pathos • logos: the logical appeal; the appeal to reason; the “embodied thought” of the text; central and subsidiary idea that the text develops (what we think) • ethos: appeal to good sense, good will, and good character of the reader and exhibits the good sense, good will and good character of the writer (how we act; morality; integrity) • pathos: appeal to the emotions or state of life of the readers (what we feel) • Rhetorical analysis reveals how the organization of the writing appeals to logos, ethos, and pathos and to the establishment of the tone of the writing. . ELEMENTS OF RHETORICAL ANALYSIS: • Effective analysis must consist of a careful exploration of three things beyond basic content: • purpose • context • audience TONE Tone is the unifying emotional content of a piece of writing. Tone refers to the author’s perception and presentation of the material and the audience. Tone is an author’s attitude toward his/her subject; it represents the relationship the author has toward the subject. The author’s attitude may be formal: uses diction & syntax that are academic, serious, and authoritative informal: is more conversational and engages the reader on an equal basis ADJECTIVES THAT DESCRIBE TONE • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • Bitter Sardonic Sarcastic Ironic Mocking Scornful Satiric Vituperative Scathing Confidential Factual Informal Facetious Critical Resigned Astonished Objective • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • Naïve Joyous Spiritual Wistful Nostalgic Humorous Pedantic Didactic Inspiring Remorseful Disdainful Laudatory Mystified Compassionate Reverent Lugubrious Elegiac • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • Macabre Reflective Maudlin Sentimental Patriotic Detached Angry Sad Playful Solemn Sincere Cynical Informative Scientific Educated Witty Tools to achieve tone • • • • • • • • Diction Syntax Imagery Facts Symbols Irony Foreshadowing Narration DICTION Diction is Word Choice: why does the author choose one word as opposed to another? Diction is an essential building block of composition. When analyzing diction, some features to look for are: general or specific words; formal or informal language; abstract or concrete nouns; Latinate (polysyllabic) or Anglo-Saxon (monosyllabic) words; jargon, slang, or colloquial words; and, of course, denotation and connotation. Elements of Diction • Denotation: the dictionary definition of a word; the most specific or direct meaning • Connotation: the associations or moods that accompany a word (determines the author’s tone and purpose) • Euphemism: substitution of a mild, inoffensive, indirect, or vague term for a harsh, blunt, or offensive one (passed away) • Onomatopoeia: the sound of a word imitates the thing or action associated with it (thud, bang, tinkle) • Pun: a play on words, usually humorous, that calls attention to a particular point SYNTAX Syntax is the arrangement of words. It is the study of the rules of grammar that define the formation of sentences. Many rhetorical devices are syntactic. Rhetorical analysis consists of analyzing the methods the author employs to convey his attitude, conviction, or opinion about a particular subject. You are not analyzing what the author is saying; you are analyzing how the argument is created. Elements of Syntax Elements of syntax are called schemes. While there are several categories of schemes, we will deal with the most common schemes found in prose works. ALLITERATION • The repetition of a phonetic sound (usually a consonant) at the beginning of several words in a sentence • Effect: emphasis; to call attention to the words and fix them in the reader’s/listener’s mind • Peter Piper picked a peck of pickled peppers. • A moist young moon hung above the mist of a neighboring meadow. JUXTAPOSITION • Putting two contrasting ideas together • Effect: contrast; dramatic effect • “My goodness is often chastened by my sense of sin.” • The gasoline savings from a hybrid car as compared to a standard car seem excellent until one compares the asking price of the two vehicles. PARALLELISM • Similarity of structure in a pair or series of related words, phrases, or clauses • Effect: balance, rhythm, and clarity; equality between parts of sentences; coherence • “I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed…I have a dream that one day on the red hills of Georgia…I have a dream that the state of Mississippi…will be transformed…I have a dream that my four little children…I have a dream today.” • We will fight them on the beaches, and fight them in the hills, and fight them in the forests, and in the villages of the dell. From Clark Kerr, The Uses of the University. Copyright 1963. He [the president of a large, complex university] is expected to be a friend of the students, a colleague of the faculty, a good fellow with the alumni, a sound administrator with the trustees, a good speaker with the public, an astute bargainer with the foundations and the federal agencies, a politician with the state legislatures, a friend of industry, labor, and agriculture, a persuasive diplomat with donors, a champion of education generally, a supporter of the professions (particularly law and medicine), a spokesman to the press, a scholar in his own right, a public servant at the state and national levels, a devotee of opera and football equally, a decent human being, a good husband and father, an active member of the a church. How does this sentence carry meaning, both in the words, in its length, and in the grammatical structure? ISOCOLON • Parallel elements are similar not only in structure but in length (that is, the same number of words, even the same number of syllables) • Effect: rhythm • His purpose was to impress the ignorant, to perplex the dubious, and to confound the scrupulous. ANTITHESIS • The juxtaposition of contrasting ideas, often through parallel structure • Effect: contrast; emphasis • Though studious, he was popular; though argumentative, he was modest; though inflexible, he was candid; and though metaphysical, yet orthodox. Dr. Samuel Johnson on the character of the Reverend Zacariah Mudge, in the London Chronicle, May 2, 1769 • That’s one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind. Neil Armstrong, as he stepped on the moon, Sunday, July 20, 1969 ANASTROPHE • Inversion of the natural or usual word order • Effect: emphasis; focusing attention • Rich, famous, proud, a ruling despot Pope might be—but he was middle-class! V.S. Pritchett, from a review in the New York Review of Books, February 27, 1969 • Backward run the sentences, till reels the mind. (From a parody of the style of Time magazine) CHIASMUS • Reversal of grammatical structures in successive phrases or clauses (without repetition) • Effect: emphasis; balance; reinforces antithesis • Those gallant men will remain often in my thoughts and in my prayers always. • “. . .(without the arrogance of false humility and without the false humbleness of pride). . .” The Bear, William Faulkner, p. 296. ANTIMETABOLE • Repetition of words in successive clauses in reverse grammatical order • Effect: reinforce antithesis • “Let us never negotiate out of fear, but let us never fear to negotiate.” John F. Kennedy, Inaugural Address, January 20, 1961 • Ask not what your country can do for you, but what you can do for your country.” John F. Kennedy, Inaugural Address, January 20, 1961 ANAPHORA • Repetition of the same word or words at the beginning of successive phrases, clauses, or sentences • Effect: emphasis; rhythm; appeal to pathos • We shall fight on the beaches, we shall fight on the landinggrounds, we shall fight in the fields and in the streets, we shall fight in the hills. Winston Churchill, speech in the House of Commons, June 4, 1940 • It is 1969 already, and 1965 seems almost like a childhood memory. Then we were conquerors of the world. No one could stop us. We were going to end the war. We were going to wipe out racism. We were going to mobilize the poor. We were going to take over the universities. Jerry Rubin, from an article in the New York Review of Books, February 13, 1969 EPISTROPHE • Repetition of the same word or words at the end of successive phrases, clauses, or sentences • Effect: emotional emphasis; appeal to pathos • The government of the people, by the people, and for the people shall not perish from this earth. Abraham Lincoln, Gettysburg Address, November 19, 1863 • As long as the white man sent you to Korea, you bled. He sent you to Germany, you bled. He sent you to the South Pacific to fight the Japanese, you bled. Malcolm X EPANALEPSIS • Repetition of the beginning word of a clause or phrase at the end of the clause or phrase • Effect: emphasis; appeal to pathos • Common sense is not so common. • “Possessing what we were unpossessed by, Possessed by what we now no more possessed.” Robert Frost, “The Gift Outright” ANADIPLOSIS • Repetition of the last word of one clause at the beginning of the following clause • Effect: emphasis; a sense of logical progression; or, for the sake of beauty • Having power makes it [totalitarian leadership] isolated; isolation breeds insecurity; insecurity breeds suspicion and fear; suspicion and fear breed violence. Zbigniew K. Brzezinski, The Permanent Purge, Politics in Soviet Totalitarianism • Queeg: “Aboard my ship, excellent performance is standard. Standard performance is sub-standard. Substandard performance is not permitted to exist.” Herman Wouk, The Caine Mutiny CLIMAX • Arrangement of words, phrases, or clauses in an order of increasing importance • Effect: emphasis • I think we’ve reached a point of great decision, not just for our nation, not only for all humanity, but for life upon the earth. George Wald, “A Generation in Search of a Future,” speech delivered at MIT on March 4, 1969 ASYNDETON • The omission of conjunctions between a series of words, phrases, or clauses • Effect: hurried rhythm; strong climactic effect; synonymity; unpremeditated multiplicity • “…that we shall pay any price, bear any burden, meet any hardship, support any friend, oppose any foe to assure the survival and success of liberty.” John F. Kennedy • I came, I saw, I conquered. POLYSYNDETON • Deliberate use of conjunctions between each word, phrase, or clause • Effect: multiplicity; energetic enumeration; intensity and emphasis; flow and continuity; produces a solemn note; slows the rhythm • This semester I am taking English and history and biology and mathematics and sociology and physical education. METAPHOR • An implied comparison between two things of unlike nature that yet have something in common • Effect: clarity; beauty of language • Write your own example. • Allegory: an extended or continued metaphor • Parable: an anecdotal narrative designed to teach a moral lesson SIMILE • An explicit comparison between two things of unlike nature that yet have something in common • Effect: clarity • Write your own example SYNECDOCHE • A figure of speech in which the part stands for the whole, the whole for a part, or any portion, section or main quality for the whole or the thing itself • Genus substituted for species: weapon for sword, arms for rifles, vessel for ship • Species substituted for genus: bread for food • Part substituted for the whole: hands for helpers, roofs for homes • Matter for what is made from it: silver for money, waves for ocean METONYMY • A type of metaphor in which the name of one thing is substituted for another with which it is closely associated • Effect: definition; commentary • White House for the President; bottle for wine; City Hall for government (You can’t fight city hall.) PERSONIFICATION • Investing abstractions or inanimate objects with human characteristics • Effect: appeals to pathos • “A tree whose hungry mouth is prest Against the earth’s sweet-flowing breast.” Joyce Kilmer, “Trees” • The thunder grumbled all night as the rain slapped the windows. APOSTROPHE • Addressing an absent person or a personified abstraction • Effect: appeal to pathos • “O eloquent, just, and mighty Death! Whom none could advise, thou hast persuaded…” Sir Walter Raleigh, History of the World • “O Rose, thou art sick.” William Blake, “The Sick Rose” HYPERBOLE • Deliberate exaggeration • Effect: emphasis; heightened effect; bolsters an argument • I said ‘rare,’ not ‘raw.’ I’ve seen cows hurt worse than this get up and get well. • We walked along a road in Cumberland and stooped, because the sky hung so low. Thomas Wolfe, Look Homeward, Angel LITOTES • Deliberate use of understatement formed by denying the opposite • Effect: enhances and intensifies the expression; ironic sentiment • Heat waves are not rare in the summer. • It isn’t very serious. I have this tiny little tumor on the brain. J. D. Salinger, The Catcher in the Rye RHETORICAL QUESTION • Also called erotema • Asking a question whose answer is obvious or assumed • Effect: asserting or denying something obliquely; persuasion • If not now, when? • Is justice then to be considered merely a word? OXYMORON • Two words that together create a contradiction; a paradox reduced to two words • Effect: complexity, emphasis, or wit; produces a startling effect • “I must be cruel only to be kind.” Shakespeare, Hamlet • Jumbo shrimp • “Why then, O brawling love! O loving hate!... O heavy lightness, serious vanity!” Shakespeare, Romeo and Juliet PARADOX • An apparently contradictory statement that contains a measure of truth • Art is a form of lying in order to tell the truth. Pablo Picasso • “The child is father to the man.” William Wordsworth, “My Heart Leaps Up” ALLUSION • A short informal reference to a famous person, event, place, or literary work • Effect: to explain (by making a sort of analogy), clarify, or enhance; to introduce variety • “…just as the Apostle Paul left his village of Tarsus…so am I compelled to carry the gospel of freedom beyond my own home town.” Martin Luther King, Jr., Letter from Birmingham Jail • If you take his parking place, you can expect World War II all over again.” ANALOGY • A relational comparison of or similarity between two objects or ideas • Effect: clarity; explanation of a thought process; establishment of a pattern of reasoning • Knowledge always desires increase; it is like fire, which must first be kindled by some external agent, but which will afterwards propagate itself. Samuel Johnson • When I think of the final exam in English, I think of dungeons and chains and racks and primal screams. SYLLOGISM • A three-part argument construction in which two premises lead to a truth • Effect: appeal to logos; defense of a truth; conclusion • All human beings are mortal. Heather is a human being. Therefore, Heather is mortal. ZEUGMA • Two or more elements in a sentence are tied together by the same verb or noun; especially acute if the verb or noun does not have the exact same meaning in both parts of the sentence • Effect: economy (saves repetition); connects thoughts and shows relationships between ideas • She dashed his hopes and out of his life when she walked through the door. • A man could lose himself in Los Angeles as easily as a cufflink. -Benjamin Black, The Silver Swan, p. 228. • Copernicus’s book describing the revolutions of the sun and planets caused a revolutionary change in man’s perspective of himself in the universe. Style “Style is a thinking out into language.” Cardinal Newman The Greeks conceived of style as that part of rhetoric in which we take the thoughts collected by invention and put them into words for the speaking out in delivery. “Style, in its finest sense, is the last acquirement of the educated mind; it is also the most useful.” Alfred North Whitehead Style • “Style is this: to add to a given thought all the circumstances fitted to produce the whole effect which the thought is intended to produce.” Stendhal • Jonathan Swift defined style as “proper words in proper places.” • There cannot be such a thing as an absolute “best style.” A writer must be in command of a variety of styles in order to draw on the style most appropriate to the situation. Style How do writers acquire the variety of styles needed for the variety of subject matter, occasion, and audience that they are bound to confront? The classical rhetoricians taught that person acquired versatility of style three ways: 1. Through a study of precepts or principles 2. Through imitation of the practices of others 3. Through practice in writing ANALYZING STYLE Features you can look for when analyzing prose style: 1. Kind of diction 2. Length of sentences 3. Kinds of sentences 4. Variety of sentence patterns 5. Coherence devices 6. Figures of speech 7. Paragraphing (length, development, transitional devices) KINDS OF SENTENCES • Grammatical: simple, compound, complex, compound-complex • Rhetorical: loose (cumulative), periodic, balanced, antithetical • Functional: statement, question, command, exclamation RHETORICAL SENTENCES • Loose (cumulative): the independent clause comes first, followed by one or more dependent clauses • Periodic: a sentence with several dependent clauses that precede the independent clause The effect of a periodic sentence is that it saves the important part of the sentence until the end, creating eagerness on the part of the listener/reader. Example: After planning the menu, shopping for the ingredients, assembling the recipes. And preparing each dish, Marie finally sat down and ate dinner with her family. Some interesting observations can be made about a person’s style and habits of thought by studying the kinds of sentences used and the proportions in which the various kinds are used. W. K. Wimsatt, in his valuable study The Prose Style of Samuel Johnson, saw in Dr. Johnson’s persistent use of parallel and antithetical clauses a reflection on the bent of his mind: “Johnson’s prose style is a formal exaggeration—in places a caricature—of a certain pair of complementary drives, the drive to assimilate ideas, and the drive to distinguish them—to collect and to separate.” And so Dr. Johnson disposed his collection of ideas in parallel structures; he reinforced the distinctions in ideas by juxtaposing them in antithetical structure.