Frederick R.Tench - Virginia Commonwealth University

advertisement

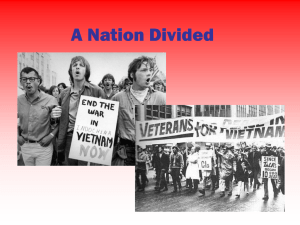

Running head: PRESIDENT JOHNSON AND VIETNAM President Johnson and the Challenge of the Vietnam War Frederick R.Tench Virginia Commonwealth University 1 PRESIDENT JOHNSON AND VIETNAM President Johnson and the Challenge of the Vietnam War Lyndon Baines Johnson became the 36th President of the United States on November 22, 1963 upon the tragic assassination of John F. Kennedy. He combined his consummate political skills and the mandate of a landslide presidential election victory in 1964 to implement longlasting and overdue domestic policies. His accomplishments included major civil rights legislation, successful anti-poverty programs, and enduring health initiatives (Bornet, 1983). However, Johnson’s record in foreign affairs has suffered in comparison. In particular, his policies and handling of the country’s involvement in the Vietnam War have been intensely criticized and labeled as failures in most aspects (Bornet, 1983). Three objectives dominated Johnson’s Vietnam decision making: he wanted to ensure the war did not hinder the passage of his domestic programs, he was committed to stopping the spread of Communism in Southeast Asia, and he longed to protect his historical reputation (Herring, 1994). To satisfy those goals, he relied on the same type of leadership style and political framing that served him throughout his political career. Yet, he was soon to learn that this approach did not work well for resolving his Vietnam War dilemma. Johnson’s knowledge of legislative procedures and political astuteness and larger-thanlife personality enabled him to shrewdly maneuver his proposed domestic programs through Congress (Dallek, 1998). He was the consummate political operator with a deep understanding about political power – how to get it, how to use, and how to keep it. According to Bolman and Deal (2008), all organizations have a political frame which views organizations as places of conflicting viewpoints, scare resources, and struggles for power. They contend that the central concepts of the political frame are power, conflict, competition, and organizational politics in which developing an agenda and a power base is a leader’s basic challenge (Bolman & Deal, 2 PRESIDENT JOHNSON AND VIETNAM 3 2008). Johnson’s combination of personal dominance and uncanny political skill enabled him to fully develop those precepts in the domestic arena. By comparison, the new and adaptive challenge of ensuring the success of his domestic programs while conducting the Vietnam War and protecting his historical legacy required a different type of leadership and political framing mindset from Johnson. An adaptive challenge by definition is a challenge confronting a community or organization for which it has no preexisting resources, remedies, tools, solutions, or even the means for accurately naming and describing the challenge (Drath, 2001). Johnson struggled with the uniqueness and complexity of the Vietnam War. His miscalculated political strategies, stringent hands-on management style, and rigid leadership principles doomed his Vietnam War effort (Berman & Routh, 2003). As a result, his historical legacy was tarnished. Several lessons for today’s leaders can be extracted from Johnson’s leadership principle and political framing. One is that leadership by personal dominance can be very restrictive in complicated situations. A second lesson is that open dialogue, inclusion, and trust are essential ingredients for overcoming an adaptive challenge (Drath, 2001). A final lesson is that leaders should be politically realistic, resilient and judicious (Bolman & Deal, 2008). They must avoid misusing their power, focus on building relationships, and be prepared to negotiate and compromise to accomplish their goals (Bolman & Deal, 2008). Domestic Affairs Legislative Accomplishments Johnson saw himself as a domestic leader first, and consequently, focused the earliest years of his Presidency on those issues (Bornet, 1983). According to Bornet (1983), Johnson was completely familiar with the machinery of the legislative process and was determined to use PRESIDENT JOHNSON AND VIETNAM 4 it fully. With the mandate of a landslide election in hand, he began his “Great Society” plan. The Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Voting Rights Act, Head Start, Medicaid, Medicare, and many less prominent but equally important acts were passed in rapid succession cementing his reputation among historians and political scientists as one of America’s greatest domestic presidents (Bornet, 1983). He also led the enactment of other important initiatives such as environmental protection laws, food stamps, public radio and television, and numerous consumer protection laws (Dallek, 1998). His highest Great Society priority was broadening educational opportunities and enriching the quality of school offerings (Dallek, 1998). Consequently, he substantially increased financial aid, and the passage of his Elementary and Secondary Act (ESEA) and Higher Education Act (HEA) improved the country’s educational system immeasurably (Dallek, 1998). Johnson not only designed unprecedented federal legislation but also developed several new agencies and cabinets. For example, he created the Office of Economic Opportunity which actively fought poverty through community action, the Job Corps, work training, work-study, and adult education (Dallek, 1998). He also established the Neighborhood Youth Corps, Volunteers in Service to America, and Aid to Families with Dependent Children (Dallek, 1998). In addition, he created the Department of Housing and Urban Development and the Department of Transportation (Bornet, 1983). Furthermore, he funded the National Endowments for the Arts and Humanities (Dallek, 1996). In short, Johnson’s unrelenting efforts on behalf of the public programs for which he hoped to be remembered translated into extraordinary accomplishments (Dallek, 1998). Political Skills PRESIDENT JOHNSON AND VIETNAM 5 Johnson was successful in the domestic political frame for a number of reasons. For one, he controlled the agenda. He had a well-conceived plan for passage of his Great Society program and followed it through. In addition, he mapped out his political terrain by identifying the principal agents of influence, by building coalitions, and by negotiating from a position of strength (Bolman & Deal, 2008). What Johnson did so successfully was first to develop a program of legislation, then forge the necessary coalitions to carry the bills, and finally to perfect the timing that would be crucial to pacing consistent achievement, using his enormous knowledge of the congressional mind to work out practical rewards and punishments (Bornet, 1983). Without a doubt, he had political power, knew how to use it, and was determined to do so. Vietnam War Goals and Challenges After these remarkable domestic achievements, President Johnson focused much of his attention on foreign affairs, specifically the growing United States’ presence in Vietnam. Since the 1950s, America had limited its involvement in Vietnam to funding, equipping, and advising the South Vietnamese government in its struggle against a Hanoi-directed insurgency (Logevall, 2004). However in 1965 Johnson entered the country into large-scale war in Vietnam after being advised by administrative insiders that Communist-led forces would take over in South Vietnam in a few months thereby putting all of Southeast Asia at risk (Herring, 1994). At that time Johnson had several stated goals: ensure that the communist aggression did not succeed; make it possible for South Vietnam to build their country and their future in their own way; and convince Hanoi that working out a peaceful settlement was to the advantage to all concerned (Bornet, 1983). After making the commitment to greater involvement, Johnson soon faced a variety of political and military issues. PRESIDENT JOHNSON AND VIETNAM 6 The significance of Johnson’s Vietnam War challenge involved three crucial considerations. First, Johnson was convinced that losing Vietnam would jeopardize major pieces of Great Society legislation and lead to the eventual undoing of his domestic accomplishments (Logevall, 2004). He was aware that the United States was not in the mood for a long and unpopular war. However he gambled on a short term strategy of escalation hoping to resolve the mounting foreign crisis long enough to hold onto public and congressional support for his domestic priorities (Logevall, 2004). Second, he was wary of a domino effect in Southeast Asia if Vietnam fell to the communists (Herring, 1994). Johnson was convinced that communist powers China and the Soviet Union would intervene not only in Vietnam but also in other Asian countries if the United States did not do something about Vietnam. Third, he wanted to protect his historical legacy and avoid being labeled as the first president to lose a war (Herring, 1994). Political Miscalculations Johnson’s initial approach to the war was cautious and calculating. He incorporated the major tenets of limited war theory at the beginning of the Vietnam entanglement war because it was much easier than waging a full-scale war (Herring, 1994). The tenets of limited war theory called for quiet, step-by-step expansion of military pressures in ways that minimized the risks of expanded conflict (Herring, 1994). However, the North Vietnamese did not respond as limited war theory said they should, presenting enormous management problems for Johnson (Herring, 1994). North Vietnamese troops engaged in guerilla warfare, mounted their own offensives, and aggressively resisted American and South Vietnamese attacks (Herring, 1994). More poor decisions by Johnson followed: overreliance on air power, ineffective ground offensives, and illconceived military campaigns (Berman & Routh, 2003). In time, the limited war escalated into a commitment of 525,000 troops, billions of dollars in expenditures, and a deeply divided PRESIDENT JOHNSON AND VIETNAM 7 American public (Berman & Routh, 2003). More tragically, 222,351 American service personnel were either killed or wounded and 352,000 Vietnamese civilians lost their lives (Bornet, 1983). The consequences of escalation and eventual withdrawal without victory were devastating for Johnson. The War in Southeast Asia, America’s first defeat in a foreign war, destroyed the momentum for his Great Society agenda and his hopes of historical standing as a great president (Dallek, 1996). Even more perplexing for historians was why he failed to take the necessary political calculations necessary to protect his administration from a stalemate or even failure in Vietnam (Dallek, 1996). Johnson’s impulse to expand war in Vietnam without public discourse grew out of developments in twentieth century politics in which he paid a major part (Dallek, 1996). He was used to setting agendas, controlling discussion, building coalitions, bargaining, and negotiating on his own terms (Bolman & Deal). His urge to control everything exacerbated an already serious problem in Vietnam (Herring, 1994). He sought to run the war as he ran his government, with scrupulous attention to detail, intolerance of any dissent, and avoidance of much-needed debate on strategic issues (Herring, 1994). For a political situation and military operation the scale of Vietnam, this was not an effective leadership approach. According to Bolman and Deal (2008), political leaders recognize that power is essential to their effectiveness; they also know to use it judiciously. It’s clear that Johnson misused power and miscalculated the political landscape with far-ranging negative consequences. Johnson’s Adaptive Challenge Commander-in-Chief One reason Johnson failed in meeting his adaptive challenge was his poor management of the war. He was used to being in charge and perceived his role as commander-in-chief as another PRESIDENT JOHNSON AND VIETNAM 8 opportunity to personally dominate at the presidential level. Yet, the conduct of the Vietnam War and the decision making process called for nuanced and engaged dialogue among domestic, foreign, and military advisors. Johnson’s highly personalized hands-on style marked the conduct of the war; however, it resulted in a strategic vacuum and massive intrusion at the tactical level - micromanagement without real control (Herring, 1994). The most glaring deficiency in his war management was the lack of strategy (Herring, 1994). He was also ineffective in dealing with his military advisors and Joint Chiefs (Herring, 1994). Another problem was the lack of coordination of the numerous elements of what developed into a sprawling, multifarious war effort (Herring, 1994). In short, his political acumen and personal dominance style failed him in Vietnam. The way he ran his government with scrupulous attention to detail, his intolerance for any form of dissent, and his unwillingness for much needed debate doomed his ability to meet his adaptive challenge (Herring, 1994). Political Failures A second reason for Johnson’s inability to overcome his adaptive challenge was that his commitment to carrying out his domestic agenda clouded his judgment and decision-making. Bator (2008) contends there was nothing more that Johnson cared about in 1965 than carrying out his domestic program and protecting Great Society legislation despite the growing issue of Vietnam. This set the tone for his future Vietnam War decisions. He wanted some activity in Vietnam but not full escalation as he feared that would doom his domestic plans --- he did not want Congress or the American public to feel they had to choose between guns and butter (Bator, 2008). Accordingly, Johnson hesitated to ask for a full appropriation needed to cover the first year costs of the war fearing it would help the enemies of his domestic legislative program (Bator, 2008). Simply stated, he failed to adequately address the challenge of the growing PRESIDENT JOHNSON AND VIETNAM 9 Vietnam challenge. Instead he decided not to mobilize the military reserves, not to request a general tax increase for 1966, and not to publicize the anticipated manpower needs in order to accomplish the limited political objective (Berman & Routh, 2003). As the war rapidly escalated Johnson found that he could not wage a war against poverty at home and against the Viet Cong in Asia without public backing, and his actions soon created a credibility gap from which he never recovered (Berman & Routh, 2003). Lastly, his political skills failed him. His political career had been largely the product of back room discussion and private manipulations; moreover, it was not his personal political style to make policy by debate (Dallek, 1996). In contrast, he was an imperious character who made his way in politics by dominating everyone around him and dominating people by the sheer force of his personality (Dallek, 1996). His insularity and disregard of other perspectives eventually caused him to become defensive, secretive, and withdrawn. His failure of candor led to a widespread feeling that the president had lied and bamboozled the country into war (Bator, 2008). According to Berman and Routh (2003), analysis of public opinion suggests that Johnson was both unresponsive to public opinion toward American involvement in Vietnam and ineffective in trying to lead and direct that public opinion. He was also defensive to the charge that he did not consult the public and Congress and enraged by talk of a credibility gap (Dallek, 1996). The master of the parliamentary art had proven not to be a master of the executive art (Bornet, 1983). Why did Johnson’s political framing fail him in Vietnam? In contrast to his domestic legislative actions, Johnson could not dictate the direction of the Vietnam War. The political power he wielded so forcefully to get his domestic agenda passed was diluted in Vietnam War negotiations. Logevall (2004) argues that Johnson knew that formidable players in Congress and PRESIDENT JOHNSON AND VIETNAM 10 elsewhere opposed Americanizing the war, and he was not at all certain that his side would win the debate. Since he had no bargaining power, he decided instead that there would be no national debate and the United States would go to war on the sly (Logevall, 2004). This proved to be a costly political miscalculation --- one that ultimately led to the end of his Presidency. In short, he failed to read the political landscape correctly and did not adequately develop an effective political network of supporters for his Vietnam policy. There is no doubt that he was unsurpassed in his knowledge of the workings of official Washington, in his ability to get contentious legislation through Congress, in his skill at arm twisting; it is far less clear that he understood the broader political forces in the country at large (Logevall, 2004). Conclusion and Lessons Learned When Johnson assumed the presidency, he was committed to continuing Kennedy’s domestic legacy which he adroitly accomplished with legislative skill and political will. Many of Johnson’s programs have become bedrocks of American life. Evidence clearly shows that Johnson’s presidency was a force for change in its efforts to guarantee civil rights, to wage war on poverty, to provide medical care for the needy, and to educate the nation’s youth (Bornet, 1983). However, scholars have long debated his handling of the Vietnam War and concede that Johnson’s escalation of the war in Vietnam overshadowed his remarkable domestic triumphs. His strong personal dominance principle worked well for setting direction, creating commitment, and facing adaptive challenges domestically. He was in control and totally committed to his domestic programs. However, his personal dominance leadership style failed him in Vietnam. He had difficulty setting a war direction and was not open to either differences of opinion or to sharing decision-making responsibilities. Moreover, he was not truly committed to the war effort until it was too late. PRESIDENT JOHNSON AND VIETNAM 11 Johnson thrived when he was able to operate within a controlled and familiar political frame. When he could set agendas, work a room, and make bargains as he did when passing Great Society reforms and programs - he was at his best. In contrast, when he left his comfort zone and had to operate within a different political landscape that involved change, lack of control, and inclusion - he blundered terribly. To overcome his Vietnam War challenge, Johnson needed more than political skill, intimidation, and power. Rather, his challenge called for open dialogue, inclusion, and trust - all difficult tasks for Johnson. The essential leadership lesson from Johnson’s Vietnam failure is that there are significant limits to personal dominance leadership when applied to complex and multilayered situations. Equally important as a take-away is that a leader with a personal dominance style must be willing to reframe as necessary, to embrace diversity, and to seek collaboration. A final lesson is that leaders should understand that appropriate and flexible coalition building, networking, and political mapping are essential for effective political framing. PRESIDENT JOHNSON AND VIETNAM 12 References Bator, F. M. (2008, June). No good choices: LBJ and the Vietnam/Great Society connection. Diplomatic History, 32(3), 309-340. Berman, L. A., & Routh, S. R. (2003). Why the United States fought in Vietnam. Annual Review of Political Science, 6(1), 181-204. Bolman, L. G., & Deal, T. (2008). Reframing organizations: Artistry, choice, and leadership (4th ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. Bornet, V. D. (1893). The Presidency of Lyndon B. Johnson. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas. Dallek, R. (1996). Lyndon Johnson and Vietnam: The making of a tragedy. Diplomatic History, 20(2), 147-162. Dallek, R. (1998). Flawed giant: Lyndon Johnson and his times, 1961-1973. New York: Oxford University Press. Drath, W. (2001). The deep blue sea: Rethinking the source of leadership. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. Herring, G. C. (1994). LBJ and Vietnam: A different kind of war. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press. Logevall, F. (2004). Lyndon Johnson and Vietnam. Presidential Studies Quarterly, 34(1), 100112.