superannuation being used to expand union power and influence.

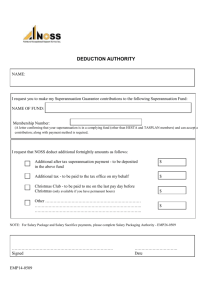

advertisement

”Superannuation’s Role in Advancing the Power and Economic Influence of the Union Movement” Speech to HR Nicholls Society Introduction It is a great pleasure to be here today to speak to this important conference of the HR Nicholls Society. I want to speak today about the role of superannuation in advancing the power and economic influence of the union movement. In the early nineties, when ACTU secretary Bill Kelty was agitating for the Hawke Keating government to legislate 6 per cent superannuation, and to double it again by the end of the decade, many were asking what he was doing about declining union membership.1 Since that time the share of the workforce who are union members has continued to fall: it now stands at a mere 18 per cent, and only 13 per cent amongst private sector employees.2 Yet through the sharp growth in the size and economic importance of two kinds of union-linked superannuation funds – industry funds and public sector funds – the union movement has gained a new source of power and influence. Thanks to decisions of the Hawke Keating Government – reinforced by more recent policies of the Rudd Gillard Rudd Government – the structure and governance of today’s superannuation system suits the interests of the union movement, and union officials, very nicely indeed. 1 Bill Kelty, Transcript of Speech to National Press Club, Wed 31 July 1991, Department of the Parliamentary Library. 2 ABS, 631 0 .0, Employee Earnings , Benefits And Trade Union Membership, August 2012 1 I want to emphasise that the Coalition supports superannuation, and our superannuation savings pool is a key national asset. Whether the current governance arrangements are the best ones for the task is a very different question. Nor does the Coalition prefer any one sector of the superannuation industry over any other sector. Our preference is for an efficient, competitive superannuation industry which serves Australians building up savings for their retirement in the most cost-effective way. As long as different fund types are competing on a level playing field – we say good luck to all of them. Today I want to start by looking at the large and growing share of the superannuation system held by public sector and industry superannuation funds. Next, I want to highlight the very close linkages between these two types of funds and the union movement. My third proposition this afternoon is that the Rudd Gillard Rudd Government has further tilted the playing field in favour of industry and public sector funds – while ignoring recommended governance changes that would increase competition and transparency and weaken the union linkage. Finally, I want to argue that the current arrangements raise serious policy problems which must be addressed – and touch on the Coalition’s agenda in this area. The Size and Growth of the Superannuation Sector Let me start by observing that the superannuation sector has grown very strongly since compulsory superannuation was introduced, and now makes up a substantial sector of the economy. Total superannuation funds under 2 management are now almost 1.6 trillion dollars, up from $164 billion in June 1992 when compulsory superannuation was first introduced.3 Industry regulator APRA divides superannuation up into several classes of funds, two of which are of particular interest to us because they are the ones with substantial numbers of union appointed directors: industry funds and public sector funds. APRA estimates that total assets of these two types of funds stood at almost $560 billion in March 2013 – representing over 35.4 per cent of the total superannuation pie.4 A particularly striking statistic about superannuation, in my view, is that annual contributions, in the year to June 2012, were around $91 billion. This is a massive amount of money – and of this amount, around $59 billion, or 65 per cent, went to industry and public sector funds.5 In other words, while industry and public sector funds together have a bit over one third of total assets in the superannuation sector today, they are winning almost two thirds of the contributions flow coming into the sector – so they are steadily increasing their market share. Extent of union control of industry & public sector funds Why are industry and public sector funds increasing their market share? In my view, one explanation is that they enjoy some distinctive advantages in the way the current system operates. These advantages arise because of the close relationship between industry and public sector funds on the one hand, and the union movement, on the other. 3 APRA, Quarterly Superannuation Performance, March 2013 (issued 23 May 2013); Parliamentary Library calculations based on ABS and APRA data 4 APRA, Quarterly Superannuation Performance, March 2013 (issued 23 May 2013) 5 APRA, Annual Superannuation Bulletin, June 2012 (issued 9 January 2013), Table 8, p 39 3 The relationship works through the appointment of directors to the trustee companies of these funds. Under the so-called ‘equal representation’ model, mandated by the Superannuation Industry Supervision Act, up to half of the directors of an industry fund are typically appointed by a union. 6 For example, Australian Super, the largest industry superannuation fund, with $47 billion under management, has half of its directors appointed by the ACTU, and half appointed by the Australian Industry Group.7 While the equal representation provisions do not apply to public sector funds, Labor state and federal governments have taken care to entrench union appointments in the governing arrangements for public sector funds. I recently decided to examine the relationships between unions and industry and public sector funds. To do this, I started with the report issued by industry regulator APRA in January this year, Superannuation Fund-level Profiles and Financial Performance, which lists 301 individual funds and gives data for them as at 30 June 2012. Of these, there are 74 funds categorised as industry or public sector superannuation funds by APRA.8 I then went to the annual reports of each of these funds to identify their directors and their net assets. In total, these funds reported net assets of $383 billion.9 Superannuation Industry Supervision Act 1993 s 89. This requires that a so-called ‘employer-sponsored fund’ have half its directors as ‘member representatives’ and half as ‘employer representatives’, with ‘member representative’ defined as someone nominated by either the members of the fund or ‘a trade union, or other organisation, representing the interests of those members.’ There is also provision for one so-called independent director. 7 Australian Super, Annual Report 2012, p 42, p 54 8 APRA, Superannuation Fund-level Profiles and Financial Performance, June 2012, issued 9 Jan 2013, table 9 9 In most cases the annual report was for the year ended 30 June 2012. As a cross check on the figure of $383 bn derived from the annual reports, the total ‘cash flow adjusted net assets’ (column W) for industry and public sector funds in table 9 of the APRA report is $372.2 bn. This number is considerably less than the $558.6 bn reported by APRA for these two classes of funds as at March 2013. The difference appears to be due to three factors. First, Superannuation Fund-level Profiles and Financial Performance excludes some smaller funds and hence the totals it reports are smaller than system wide totals. Second, between June 2012 and March 2013 6 4 Most interesting for present purposes though is the total number of directors across these funds – and how many were appointed by unions. Across the 74 funds, it turns out when I totalled up the numbers across the annual reports, that there were 551 directors in total, and of these 171 were appointed by unions. In other words, the unions appointed 31 per cent of the directors.10 When you look at the total positions for so-called ‘members’ representatives’, the dominance of the unions was even greater. There were 41 independent directors or chairs across these funds. Of the 510 other positions, a 50:50 split would leave 255 positions as ‘member representatives.’ Of these, the unions therefore appointed over two thirds. If you just take the biggest funds, these are even more tightly linked into the union movement. The ten biggest funds, as at 30 June 2012, had total net assets of $250 billion. Across these funds, there were 112 directors in total, of which 8 were independent, and 48 union appointed directors. This means that the unions appointed 92 per cent of the 52 spots theoretically available for member representatives. To cite some examples, the biggest fund, with $47 billion, was Australian Super, with 6 of its 12 directors appointed by the unions; next was the Queensland State Public Sector Superannuation Scheme at $36 billion, with 6 of 12 directors appointed by unions; then the NSW First State Superannuation Scheme, at $33 billion, with 6 of 13 directors appointed by unions; the Retail Employees Superannuation Trust, at $22 billion, with 4 of 8 directors appointed there were significant contributions inflows, exceeding $40 billion for these two classes of funds. Thirdly, in this period equity markets were up strongly and hence asset values rose strongly. 10 The source for the figures in this paragraph and several following is the analysis I conducted as described earlier. 5 by unions; and Sunsuper at $20 billion with 3 of 6 directors appointed by unions. It is also interesting to look at the question from the other perspective: which unions are doing the appointing. Here what we see is a considerable concentration, with the largest and most powerful unions appointing directors to multiple different funds. The ACTU appoints 20 directors across seven different industry and public sector superannuation funds, which have under management in total over $100 billion. Unions NSW appoints nine directors to several different funds. The CFMEU appoints 15 directors across four funds. The Australian Workers' Union, has nine directors across seven funds. The Electrical Trades Union appoints 13 directors across six funds. As to the question of who the unions appoint, in the great majority of cases they choose to appoint union officials. Very few of them make any effort to appoint people with expertise in superannuation; or to appoint a representative selection of members of the superannuation fund – as opposed to members of the union. Consider for example TWU Super, a fund with $2.6 billion under management and 130,000 members, with four directors appointed by the Transport Workers Union. The four directors appointed are the TWU's federal secretary Tony Sheldon and three state secretaries: Wayne Forno, Wayne Mader and Jim McGiveron.11 Of course, appointments to the boards of super funds generally bring directors’ fees. At Australian Super the chair earned $160,984 in the 2012 financial year; at CBUS the chair earned $187,183 and board members earned nearly $18,000 a 11 TWU Super, 2012 Annual Report, pp 8 & 14 6 year plus a fee per meeting of $2,128; at HESTA the chair earned $76,000. 12 In some cases directors’ fees are retained by the individuals, in other cases they are paid to their appointing unions, but in either case the arrangements are quite satisfactory from the perspective of union officials and the union movement. Incidentally, I found only a few funds which disclose in their annual reports what their union-appointed directors do with the fees they receive. In most cases, fund members are none the wiser as to whether the fees are retained by those directors personally or are paid to the appointing union. There is certainly anecdotal evidence that some union officials appear to have navigated quite carefully to maximise their earning potential from union related superannuation activities. Consider for example Mr Bernie Riordan, a former secretary of the NSW Electrical Trades Union and a former president of the Australian Labor Party in NSW (before he was appointed last year by the Rudd Gillard Rudd Government to the Bench of the Fair Work Commission). Mr Riordan had previously been a director of Energy Industry Superannuation Scheme, a public sector superannuation fund for NSW energy sector workers, as well as a director of two companies which EISS part owned, FuturePlus Financial Services and Chifley Financial Services. The Sunday Telegraph reported in 2011 that Mr Riordan was at that point receiving directors’ fees from these three boards and one other totalling up to $264,625 a year.13 A statement of claim filed in the Federal Court in 2011 by Dean Mighell, secretary of the Victorian branch of the ETU, alleged that Mr Riordan had received over $1.8 million in fees since 1998 from sitting on the boards of the 12 Australian Super, 2012 Annual Report, p 51; CBUS, 2012 Annual Report, p 36; HESTA 2012 Annual Report, p 26 13 B Crawford, Bernie sued for copping mates rates, Sunday Telegraph, July 17, 2011. 7 Energy Industries Superannuation Scheme, Futureplus Financial Services, Chifley Financial Services Limited and Mert Limited.14 Another example is Mr Bob Henricks, who was the Queensland secretary of the ETU for a number of years. Until recently he was the chair of, or on the board of, three separate funds in Queensland: Electricity Supply Industry Superannuation Fund (Qld); The Allied Unions Superannuation Trust (Queensland) and SPEC Super. 15 Yet another example is Michael Williamson, the former Health Services Union boss in New South Wales, now facing a number of criminal charges. Williamson was reported last year in the Sydney Morning Herald to earn a $330,000 year salary, in addition to $150,000 from his various board positions such as First State Super.16 When you dig into the legal arrangements underpinning industry superannuation funds, you discover some interesting things. For example, LUCRF Super, described in its annual report as “Australia’s first industry fund”, has as its trustee a company called LUCRF Pty Ltd. The company has issued two ordinary shares; one is held by Mr Charles Donnelly, the General Secretary of the National Union of Workers, and one is held by Mr Timothy Kennedy, the General President of the National Union of Workers. This means that these two men have total control in appointing and removing the directors of the trustee company. In other words, this fund, with $2.9 billion under management, can be directed – on such matters as how it votes at the D Crowe, ‘Super Funds Forced to Come Clean’, The Australian, April 27, 2012 SPEC Super, Annual Report, 2011; Energy Super Annual Report 2011; AUST(Q) Superannuation Annual Report 2010–11. SPEC and Energy Super merged in 2011 and hence he is now on two boards. AUST(Q) Superannuation Annual Report 2009–10, p 16. 16 K McClymont, HSU bosses berated for 'obscene' salary levels, Sydney Morning Herald, April 14 2012 14 15 8 AGMs of companies in which it holds shares – by these two senior officials of the National Union of Workers. 17 Even more surprisingly, according to the company search these two men are the beneficial owners of the shares – that is, they own them for themselves rather than on trust for the union. At the very least that suggests that the ownership arrangements of LUCRF are rather loose. Union control has increased under Rudd Gillard Rudd Government Under the Rudd Gillard Rudd Government, the entrenched position of unions in the superannuation system has been systematically defended and extended. Until recently, the responsible Minister was Bill Shorten, who held the dual portfolios of Employment and Workplace Relations on the one hand, and Superannuation and Financial Services on the other. This combination makes perfect sense if you believe the union movement is seeking to leverage compulsory superannuation to advance its economic interests and political power. Shorten was ideally suited to advance this agenda, as a former director of a predecessor of Australian Super and a former secretary of the Australian Workers’ Union. He is one of three former directors of Australian Super who are presently federal Labor parliamentarians, along with Greg Combet and Doug Cameron. Labor’s candidate for the seat of Melbourne in 2010 and again in 2013, Cath Bowtell, is also a former director of Australian Super. For most of the current parliamentary term, she was warehoused in the role of Chief Executive of another industry fund, AGEST. 17 ASIC Historical Extract, LUCRF Pty Ltd ACN 005 502 090 conducted 2 Dec 2011. 9 Shorten claimed that much of his policy agenda in superannuation was driven by the recent Cooper Review into superannuation. However he appeared not to read the chapter of the Cooper Review dealing with fund governance. This chapter concluded that the equal representation system “no longer seems to achieve its original stated objective”.18 It observed that directors are often not elected but rather are nominated by third party organisations, such as employer associations and trade unions –and in practice these organisations do not necessarily represent all employers or employees. It also pointed out that the system leaves significant groups ‘unrepresented’, including most obviously those who are retired and receiving benefits payments from the fund. Based upon these findings, the Cooper Review recommended that the equal representation model should no longer be mandated, and where it does apply at least one third of representatives of both members and employers should be non-associated.19 Bill Shorten simply ignored these recommendations. This was not the only area where Shorten stoutly defended the interests of the unions and union-linked superannuation funds against competitive pressure. He also blocked recommendations by the Productivity Commission for changes to the current arrangements which limit competition in the choice of default superannuation funds. Julia Gillard’s Fair Work Act 2009 established so-called ‘modern awards’ – and one of the matters these cover is the specification of a ‘default superannuation fund’. 18 19 Super System Review (Cooper Review), Final Report, Chapter 2, Trustee Governance, pp 53-54 Super System Review (Cooper Review), Final Report, Recommendations 2.6 and 2.7 10 Modern awards need the approval of the Fair Work Commission – an organisation stacked with ex-union officials. So it is not surprising that modern awards overwhelmingly specify industry and public sector funds as the default superannuation fund. An analysis conducted by the Institute of Public Affairs found that across 166 ‘modern awards’, there were a total of 566 superannuation funds specified. Of these, 513 were industry funds or public funds. 20 Following growing complaints, Labor was forced to include in its 2010 election policy a promise to introduce an open, transparent and competitive process to select default funds under modern awards. The Productivity Commission was given the job of designing such a process. In its draft report in June 2012, it found the default fund arrangements ‘could be improved to promote the best interests of members’, that the primary objective should be ‘the best interests of members’ and proposed that the selection of funds should be ‘merit based.’ 21 The clear implication was that the existing process did not meet this test. The Productivity Commission said that one option to improve the process would be to establish a new body, independent of Fair Work Australia, to ‘select and assess the funds to be listed in modern awards.’22 Bill Shorten, alert to the threat to the union-linked funds, soon announced that he wanted funds to be chosen by an expert panel within Fair Work Australia.23 Shorten’s model is now law: the expert panel will advise the Fair Work L Staley, ‘Keeping Super Safe: A Call for Greater Transparency from Superannuation Funds,’ Institute of Public Affairs, April 2010, p 11 21 Productivity Commission Draft Report: Default Superannuation Funds in Modern Awards, June 2012, p 2 22 Productivity Commission Draft Report: Default Superannuation Funds in Modern Awards, June 2012, p 2 23 Bill Shorten, Minister for Financial Services and Superannuation, Media Release No 052, 22/8/2012, ‘Government Supports Evidence Based and Expert Led Process for Default Funds.’ 20 11 Commission (the renamed Fair Work Australia) on selecting default funds, but the final decision will be made by the Full Bench of the FWC. This is likely to mean that existing default funds will stay on the list in existing modern awards; and given the conservative and legalistic nature of the process, new and innovative funds are likely to have a hard time making it through the two stage process. In other words, it is a very long way from the promised open, competitive and transparent process. As a case study in the way that the Rudd Gillard Rudd Government has consistently worked to protect the interests of union linked superannuation funds – even in the face of advice from an independent agency that the arrangements were not in the best interests of those the superannuation system is supposed to serve, namely members of funds – this episode is very telling. Current arrangements raise serious policy concerns I have spoken about the current structure of the superannuation market, the dominance of union officials, and the assiduous efforts of the Rudd Gillard Rudd Government to maintain and strengthen these arrangements. In the final part of my remarks I want to argue that this raises serious policy concerns – and touch on what the Coalition intends to do should we come to power. Conflict of interest and duty (failure of sole purpose test) The first problem is that union officials who are appointed to superannuation boards potentially face a conflict between their duty to members of the superannuation fund – and their interest in advancing the position of their union. There are plenty of examples which raise concerns about such conflicts. Recently, for example, we have seen pressure applied by the Victorian branch of the CFMEU to building industry superannuation fund CBUS, following 12 an industrial dispute between the CFMEU and the construction company Grocon. In January this year, the Victorian secretary of the CFMEU, Mr John Setka, said his members were angry that CBUS had awarded Grocon a $430 million project in Sydney. 'I reckon it's a slap in the face for the union, what CBUS has done,' Mr Setka was quoted as saying. 24 The CFMEU has subsequently sought expressions of interest from other superannuation funds to become the default fund for its members. This would appear to be an attempt by a union to use the economic resources of a large superannuation fund over which it has substantial influence, including the right to appoint three directors, to secure industrial or political outcomes, in this case to advance its industrial dispute with Grocon. What would such action mean for the interests of the 655,000 members of CBUS? CBUS is pursuing a property development with a view to generating an economic return on the funds it holds for the purpose of funding the retirement incomes of members. It presumably chose Grocon as the builder offering the best value for money on the job. Yet the CFMEU wants this consideration to come second to its industrial agenda. How will the three directors of CBUS appointed by the CFMEU deal with this? Earlier I mentioned TWUSuper, a superannuation fund which has four officials of the Transport Workers Union as its directors. In 2011 the TWU vigorously attacked changes proposed by the management of Qantas to the operation of that company, changes which management said would improve the company's financial performance. 24 M Skulley, ‘CFMEU stirs up anti-CBUS campaign’, AFR, 7 Jan 2013 13 Members of TWUSuper have a right to expect that the sole consideration exercising the minds of directors of the fund is how to maximise the financial returns generated by the fund. This raises an obvious question: how do directors of TWUSuper who are also union officials think about equity investments in Qantas or in other companies in the transport sector? In theory, the duty of a director of a superannuation fund in these circumstances is clear. That duty is to ensure that the fund is maintained solely for the benefit of each member of the fund. This is the sole purpose test, set out in section 62 of the Superannuation Industry (Supervision) Act. Considerations of union interest – or personal interest – should be disregarded. Whether that always happens is far from clear. Consider the Meat Industry Employees' Superannuation Fund, which according to reports in The Australian, made a $30 million investment in a building company, Austcorp. Almost all of that money was lost when Austcorp collapsed in 2009.25 According to the report, Mr Wally Curran, a long-term secretary of the meat workers union and a long-serving director on the board of the fund, was paid significant consultancy fees by Austcorp. At the very least, this raises a question about whether there was a conflict of interest facing Mr Curran. Another example is in the July 2012 failure of the proposed merger between Vision Super and Equip Super in Victoria. Vision Super has four directors appointed by the Australian Services Union. The merged entity was supposed to have elected directors. A member of the Equip Super fund—somebody who happened to be a senior manager at a power H Thomas, ‘Unionist Wally Curran took cash from developer amid $30m super investments’, The Australian, May 18, 2012 25 14 company and a former employer-appointed director of Equip Super—chose to seek election as a board member of the merged super fund. This made the ASU very cross. In an email to ASU members, ASU state secretary Brian Parkinson had this to say: As expected, employers are seeking election to workers' positions. Indeed, one such individual, John Azaris…has exploited his senior management role to frustrate the election chances of ASU candidates…Management will pull out all the stops to see one of their own elected at the expense of workers.26 Mr Parkinson is a director of Vision Super. He has duties to the members of that fund – and the transaction was conceived as being in the interests of those members. Yet this email would suggest that his highest priority is political advocacy as state secretary of the ASU. Interestingly, just last month Vision Super pulled out of another proposed merger with another fund. Risk of cross-infection from union corruption The recent governance scandal at the Health Services Union raises an even more troubling possibility: the risk of a superannuation fund being crossinfected by corruption at a union because officials of that union are appointed to the board of the fund. Both the former national secretary of the HSU, Craig Thompson, and the former NSW President of the HSU Michael Williamson, are the subject of criminal charges relating to governance problems at the union. As is well known, Fair 26 A copy of the email was forwarded to me. 15 Work Australia found multiple breaches of union rules, including the misuse of union credit cards for personal expenditure including on prostitutes. Both men had previously been union appointed directors of superannuation funds. Craig Thompson is a former director of HESTA, a fund with $20 billion under management. Michael Williamson was until 2012 a director of First State Super, a fund with $33 billion under management for some 70,000 current and former NSW public servants. He had been appointed to that position by Unions NSW. Last year the chairman of First State Super complained that he had no power to remove Williamson as a trustee.27 The HSU scandal is powerful evidence that at least one union had a serious culture of corruption. In my view, it raises obvious questions about whether there is a systemic risk in a system in which union officials are extensively appointed as directors of superannuation funds. This is precisely the sort of risk, I would suggest, that the governance reforms recommended by the Cooper Review would help to address. Unfortunately, as I have mentioned, Bill Shorten ignored the recommendations. He did offer the comment, following the Fair Work Australia report into the HSU scandal, that he was “appalled.” I was reminded of Captain Reynaud in Casablanca who was ‘shocked’ to discover there was gambling going on – and promised to ‘round up the usual suspects.’ Long tail of small, sub-scale funds 27 S Patten, Super fund can’t sack HSU boss, Australian Financial Review, 11 April 2012 16 I spoke earlier about some of the very large industry funds like Australian Super. At the other end of the scale, there is a long tail of small superannuation funds. Let me mention for example: The Australian Meat Industry Superannuation Trust, with net assets of $1.03 billion as at 30 June 2012 The Health Industry Plan which had net assets of $621 million the Meat Industry Employees Superannuation Fund I mentioned earlier, with net assets of $547 million The Allied Unions Superannuation Trust (Queensland) which had net assets of $192 million The Transport Industry Superannuation Fund which had net assets of $86 million. In fact, there are at least twenty industry and public sector funds with net assets of less than a billion dollars. I make no criticism of the specific management of the funds I have mentioned - and it is clearly possible for small funds to deliver excellent performance. But if you were designing a system from scratch you probably would not do it this way – particularly if you were worried that small funds, closely linked to individual unions, may be more vulnerable to governance problems than larger funds. One reason for this long tail of small funds is the close relationship between the union movement and the superannuation sector. It suits key union officials for their union to have a closely linked superannuation fund over which they can exercise influence or control. 17 It is less clear that it best serves the interests of Australians who are saving for their retirement. Directors with little skill and experience who are there for the wrong reasons Another question about the present arrangements is the nature of the directors who are appointed by the unions. Most are union officials; they are generally not people with extensive skill and experience in large scale financial asset management. In too many cases, they are there because a position as a director of a superannuation fund is seen as reward for service to the union, or indeed as simply an additional part of the role of being a union official. In some of the troubling instances I have mentioned, it seems they are there because they have sniffed out an opportunity to pick up some additional fees – or even to improperly leverage the economic power of the superannuation fund to facilitate their own personal advantage. I think it is very problematic indeed that we have a system under which employees are forced, by law, to take a portion of their remuneration in the form of superannuation contributions, and yet we have not taken steps to derisk the governance of the vehicles into which that money is put. With the majority of people paying little attention to their superannuation, the default fund arrangements mean that money is being streamed into a range of funds – the size and governance quality of which is quite random from the point of view of the individual employee. Weakening of competition Another problem with the current arrangements is that they weaken competition. In my view this is a very serious issue. 18 It is well known that consumers do not always get good value for money from their funds managers. The problem is compounded in a system where the funds under management are rising strongly every year. Given the economies of scale in funds management, a management expense ratio that may be reasonable when a fund has $5 billion under management could be completely excessive when it has ten times that amount. So if we are forcing people by law to put a portion of their remuneration into superannuation funds, we should pay particular care to ensuring strong competition – as the best way to keeping fees under control. Unfortunately, today’s arrangements protect large sectors of the industry from competitive pressure. The Productivity Commission’s report into default funds presents an amusing series of arguments from industry funds and unions – including the SDU, United Voice, CBUS, LG Super and the ACTU –explaining why competition and contestability is a bad thing. 28 I felt like I was back in my Optus days, reading submissions from Telstra. The Productivity Commission gave their arguments short thrift, concluding: … enhancing contestability and providing incentives for funds to deliver improved products are essential in ensuring that the interests of employees who derive their default superannuation product in accordance with modern awards are best served. 29 Exercise of raw economic power The final issue I want to discuss is the way that the union movement has used the compulsory superannuation system to amass raw economic power. 28 Productivity Commission Final Report: Default Superannuation Funds in Modern Awards, October 2012, p 149-152 29 Productivity Commission Final Report: Default Superannuation Funds in Modern Awards, October 2012, p 153 19 Let me give some anecdotal examples. The chief executive of a major transport company told me that when his company sits down to negotiate with the union, one of the first demands is always that the union’s superannuation fund is specified as the default fund in the award. With many issues to resolve, and limited time, that is one demand which invariably gets conceded. The chief executive of a large financial services company told me about the power exercised by industry funds which award wholesale funds management mandates to companies like his. Amongst other things, they are frequently very specific in directing how the shares owned by the fund are to be voted at annual general meetings. It is not hard to see why unions might like to be able to influence and control investment decisions affecting listed companies – and to use this power to advance the industrial agenda of the union. Now it might be said that this would never happen because it would breach the sole purpose test. In my view such a statement would be naïve – and would fly in the face of the accumulated evidence. What the Coalition is going to do about it Let me close by touching briefly on what the Coalition intends to do in this area. We intend to implement some of key recommendations of the Cooper Review ignored by the government: disclosure of conflicts of interests should be mandatory directors should disclose their remuneration in line with the provisions that apply for publicly listed companies the equal representation model should no longer be compulsory where equal representation does apply, there should be at least one third of directors on the board who are independent; and 20 directors who want to sit on multiple boards must demonstrate to APRA that they don’t have any foreseeable conflicts of interest. We will also work to ensure that Australians in default superannuation funds can benefit from genuine choice and competition by ensuring any MySuper product can compete freely in the default superannuation market. Conclusion I have argued today that when the compulsory superannuation system was established by the Hawke Keating Labor Government and by the ACTU in the early nineties, one of the key objectives was to increase the power and influence of the union movement. Upon coming to power in 2007, the Rudd Gillard Rudd Government began working enthusiastically to further that agenda. The evidence is clear in the number of union officials who are on the boards of superannuation funds; the concentration of union control in the biggest funds; the substantial number of directors appointed by the large unions and union peak bodies; and the growing market share enjoyed by the industry and public sector funds, with their share of contributions running well ahead of their share of existing assets. The current arrangements raise a serious policy question. The question is not whether it makes sense to have a system of retirement savings with an element of compulsion – that is settled policy and the Coalition is clear in our support of superannuation. The question is whether key features of the present system are there because they suit the union movement – even when they may not best serve the interests of Australians saving for their retirement, the very people that the superannuation system is supposedly designed to serve. 21 I have argued today that the Rudd Gillard Rudd Government has failed to address this issue - because key decision makers come from the union movement and are personally committed to the agenda of using the superannuation system to maximise the power and influence of the union movement. It is about time that superannuation policy was determined in the interests of Australians saving for their retirement – and if the Coalition wins government that will be our priority. 22