Ad as persuasive language

advertisement

FIGURATIVE LANGUAGE USAGE IN

ADVERTISING

Pennarola, chapter VI, Leech 181-185

Rhetoric in advertising

Rhetorical figures

artful deviation from the norm. It occurs when an

expression deviates from expectation.

The two elements or domains are linked and the

nature of such link determines the type of rhetorical

figure.

By linking the two elements (or domains), the

characteristics of one are transferred to the other.

Advantages of rhetoric in advertising

Attracts attention; geting noticed

Complex rhetoric: involves comprehension, cognitive processing

and interpretation

Provides pleasure, self-contentment: pleasant feelings

Provides longer retention

(McQuarrie & Mick 2003) Visual and verbal rhetorical

tropes may sometimes create meaning incongruity =>

consumers use more cognitive effort to interpret the

advertisement.

If the effort is rewarded with relevant meanings, consumers

will appreciate the advertisement more.

Advantages of rhetoric in advertising

Advantages of rhetoric in advertising

Advantages of rhetoric in advertising

Ad as persuasive language

Persuasive language uses rhetorical tropes or figures

to reach its purposes of persuading people to buy or

use the advertised product/object/service

“A rhetorical figure occurs when an expression

deviates from expectation, the expression is not

rejected as nonsensical or faulty, the deviation occurs

at the level of form rather than content, and the

deviation conforms to a template that is invariant

across a variety of content and contexts.”

(McQuarrie / Mick 1996)

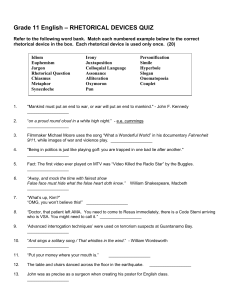

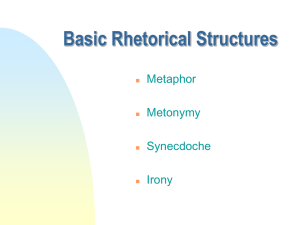

TROPES

There are four kinds of tropes mainly used in adverts:

Metaphor

(&simile)

Metonymy (& synecdoche)

Synaesthesia

Irony (& nonsense)

METAPHOR (1)

Two seemingly unrelated subjects are put in relationship (for ex.,

YOU ARE A ROSE).

-- when something is something else: the ladder of success (i.e,

success is a ladder).

"Carthage was a beehive of buzzing workers." Or, "This is your

brain on drugs."

The first object is described as being a second object.

In this way, the first object can be economically described

because implicit and explicit attributes from the second object

can be used to fill in the description of the first.

METAPHOR (2)

A metaphor consists of THREE parts:

the tenor, that is the subject to which attributes are ascribed;

the vehicle, that is the subject from which the attributes are

derived;

the ground, that is the part(s) of semantic field from which

the attributes are selected to create the relationship

between the tenor and the vehicle

(Halliday 1985)

METAPHOR (3)

Example :

All the world's a stage,

And all the men and women merely players

They have their exits and their entrances;

William Shakespeare,

As you like it 2/7

THE WORLD (TENOR)

THE STAGE (VEHICLE)

THE GROUND (SEMANTIC FIELD/ATTRIBUTES)

METAPHOR (7)

VISUAL METAPHOR

VERBAL METAPHOR

(Cook 1992: 108-109)

http://c.uglym.com/cms/show_article/333003.html

SIMILE

A simile is a figure of speech in which the subject is

compared to another subject.

Similes are marked by use of the words like or as (for

example, “He was as nervous as a long-tailed cat in

a room full of rocking chairs”).

SIMILE (2) - EXAMPLE

Visual simile: Life can be so simple (like having a cup of coffee and a cigarette)

SIMILE (2) - EXAMPLE

Visual simile: Comparing two things or ideas, usually by saying “like” or “as.” In this case,

Fiber-Castell is suggesting that the colors of its pencils are as natural as the color of a

purple eggplant.

METONYMY

Metonymy is an association created between meanings

which are contiguous rather than similar.

A rhetorical strategy of describing something indirectly by

referring to things around it.

-- using a vaguely suggestive, physical object to embody a

more general idea: CROWN for royalty; the PEN is

mightier than the SWORD.

We use metonymy in everyday speech when we refer to

the entire movie-making industry as a mere suburb of L.A.,

"Hollywood”.

Metonymy (2)

In metonymy, associations are contiguous because we

indicate:

1.

2.

3.

4.

effect for cause ('Don't get hot under the collar!' for 'Don't get angry!');

object for user ('the stage' for the theatre and 'the press' for journalists);

substance for form ('plastic' for 'credit card', 'lead' for 'bullet');

place for:

5.

event: ('Chernobyl changed attitudes to nuclear power');

person ('No. 10' for the British prime minister);

institution ('Whitehall isn't saying anything');

institution for people ('The government is not backing down').

METONYMY - Example

An ad for pensions in a

women's magazine asked

the reader to arrange four

images in order of

importance:

each image was metonymic,

standing for related

activities (such as shopping

bags for material goods).

Metonymy

Metonymy

Metonymy

Metonymy

This Mercedes-Benz ad

is of both a frontal and

side view of a man’s

face merged. The text

reads “Look to the side

without looking to the

side”, which fits the

merging of the faces.

The image is a

metaphor for the text,

and a metonymy for the

technology that is being

advertised.

Metonymy

Neckties shaped like sushi is a great

advertising example.

Tokyo is in Japan, where sushi is well

known. The relationship between

image and text is solid. The image

and text compliment each other

completely. Metaphor and

metonymy play a role in this

advertisement because of the

connection between the image

and text.

The ties shaped like sushi are a

metaphor for Tokyo , sushi is a

metonymy for Tokyo.

SYNECDOCHE

Synecdoche is like metonymy but more ‘specific’.

Part to Represent Whole

For example:

The word “bread” can be used to represent food in

general or money (e.g. he is the breadwinner; music is my

bread and butter).

The word “sails” is often used to refer to a whole ship.

The phrase "hired hands" can be used to refer to workmen.

The word "wheels" refers to a vehicle.

SYNECDOCHE

Using the whole to refer to a part is also a common practice

in speech today. For example:

At the Olympics, you will hear that the United States won a

gold medal in an event. That actually means a team from

the United States, not the country as a whole.

If “the world” is not treating you well, that would not be

the entire world but just a part of it that you've

encountered.

SYNECDOCHE (2)

Synecdoche is used when (Lanham

1969: 97):

A part of something is used for

the whole (“hands” to refer to

workers);

The whole is used for a part

(“the police” for a handful of

officers);

The species is used for the

genus (“bread” for food,

“kleenex” for facial tissue)

SYNECDOCHE (3)

Visual Synecdoche:

Referring to a whole by its

part or a part by its whole.

In this case, Heinz uses

the pieces of a tomato to

imply what the tomato,

with all its other

components, will be

come: ketchup.

The slogan instead

introduces a simile

SYNECDOCHE (3)

In photographic and filmic media a close-up is a

simple synecdoche - a part representing the whole.

Indeed, the formal frame of any visual image functions

as a synecdoche in that it suggests that what is being

offered is a 'slice-of-life', and that the world outside the

frame is carrying on in the same manner as the world

depicted within it.

Synecdoche invites or expects the viewer to 'fill in the

gaps' and advertisements frequently employ this

trope.

Any attempt to represent reality can be seen as

involving synecdoche, since it can only involve

selection (and yet such selections serve to guide us in

envisaging larger frameworks).

SYNECDOCHE (3)

The Nissan ad shown here was

part of a campaign targetting a

new model of car primarily at

women drivers (the Micra). The

ad is synecdochic in several

ways:

• it is a close-up and we can

mentally expand the frame;

• it is a 'cover-up' and the

magazine's readers can use

their imaginations;

• it is also a frozen moment and

we can infer the preceding

events.

IRONY

In IRONY, the signifier of the ironic sign seems to

signify one thing but it actually signifies something

very different.

Where it means the opposite of what it says (as it

usually does) it is based on binary opposition.

IRONY

Irony reflects the opposite of:

the

'I

the

thoughts or feelings of the speaker or writer

love it' = I hate it

truth about external reality

'There's

a crowd here' = it's deserted

IRONY

Substitution can be based on dissimilarity

understatement)or disjunction (as in exaggeration)

dissimilarity

disjunction

(as

in

IRONY (2)

This ad from the same Nissan

campaign illustrated earlier

makes effective use of irony.

We notice two people: in soft

focus we see a man absorbed

in eating his food at a table; in

sharp focus close-up we see a

woman facing him, hiding

behind her back an open can.

As we read the label we

realize that she has fed him

dog-food (because he didn't

ask before borrowing her car).

SYNAESTHESIA

It is a peculiar form of metaphor

In linguistics, it is the production from a senseimpression of one kind of an associated mental

image of a sense-impression of another kind

SYNAESTHESIA (2)

Synaethesia is amply used by copywriters because it

represents the hedonistic invitation to enjoy all the senses

Lips that scream with colour (Rimmel)

For colour at its softest (l’Oreal)

Synaesthesia

Other tropes

Hyperbole (= exaggeration; sometimes = irony)

An interior fit for an emperor (Peugeot)

To the moon and back four times a day (United Airlines)

Discover colours so pure it blushes with you. Introducing

Blushing Micronised Cheek Colour (Estée Lauder)

Other tropes

Antonomasia

Any single entity appearing in the advert text

becomes the representative of its category

The Make-Up of Make-Up Artists (Max Factor)

Nespresso. What else? (Nescafè)

Carte Noir. French for Coffee

Audemars Piguet. The master watchmaker

Other tropes

Tautology

Self referential quality of advertising discourse

It can be merely visual: the whole advert text consists of the

photo of the product simply accompanied by the brand name

as if the product did not require any introduction

It’s a Volvo. It’s a Volvo (we printed it twice in case you didn’t believe the

first time) (Volvo)

NEW, NEW, NEW, NEW, NEW, NEW, NEW, NEW, NEW, NEW, NEW, AND

NEW

New Bodyform Invisible – with 12 improvements

Other tropes

Anaphora

It is the repetition of one or more words within a

sentence.

It creates an effect of expectation, emphasis and

symmetry

it’s

where moths dance. it’s where laughter comes easily.

it’s where time meander. it’s where i’m always religthing

the candles. it’s where our friends come to Sunday lunch.

it’s where other don’t leave until Monday morning. It’s

where we live. it’s our habitat (Habitat)

Grice’s Cooperative Principle (1976)

The Co-operative Principle

"Make your contribution such as is required, at the

stage at which it occurs, by the accepted purpose or

direction of the exchange in which you are

engaged" (Grice 1976).

(1). A: What time is it?

B: It’s five o’clock

(2). A: It’s my birthday today.

B: Many happy returns. How old are you?

A: I’m five.

Grice’s Cooperative Principle (1976)

Conversational Maxims:

Quantity

Don’t say more than necessary

Make your contribution as informative as required

Quality

Do not say what you believe to be false

Do not say that for which you lack adequate evidence

Relevance

the contribution must be relevant, appropriate to the need.

(So, in a question, the relevant contribute will be the

answer)

Manner

be clear

avoid ambiguity

Conversational principles

One speaker may:

Violate the maxims.

Flout one or more maxims

Conversational principles

One speaker may:

Violate the maxims.

the speaker says something which is not true, and

knows that the hearer will not understand that the

utterance is not true. The speaker deliberately

tries to mislead the hearer.

A:

and you are… mmm… a doctor?

B: It is true that the addresser of the present utterance

is, at the time of speech, the legitimate holder of an

advanced degree in medicine and of a valid licence to

practice medicine in the jurisdiction in which this sentence

is being spoken.

Conversational principles

One speaker may:

Flout one or more maxims

an additional unstated meaning of an utterance has to be

assumed in order to understand an utterance

this creates the implicature

A: I am out of petrol

B: There is a garage around the corner

A: Well, how do I look?

B: Your shoes are nice.

Grice’s Cooperative Principle (1976)

It might seem that advertising would be a poor

example of “co-operation”, as that word is usually

understood: the advertiser is trying to tell you

something

you

don’t want to know

at a time when you aren’t interested

to make you do something that you wouldn’t otherwise

do.

Yet the interpretation of ads depends on “cooperation” as Grice defines it.

Grice’s Cooperative Principle (1976)

Quantity

Don’t say more

than necessary

Grice’s Cooperative Principle (1976)

Quantity

Make your

contribution as

informative as

required

Grice’s Cooperative Principle (1976)

Quality

Do not say what you belied to be

false

http://www.lavazza.com/corporate/en/avantgarde/creativelab/products/espesso.html

Grice’s Cooperative Principle (1976)

Quality

Do not say that for which you lack adequate evidence

http://www.adsneeze.com/health/ads-aquafresh-whitening-toothpaste

Grice’s Cooperative Principle (1976)

Relevance

the contribution must be relevant, appropriate to the need. So, in a

question, the relevant contribute will be the answer

http://www.adsneeze.com/health/ads-aquafresh-whitening-toothpaste

Grice’s Cooperative Principle (1976)

Manner

Be Clear

http://www.creativereview.co.uk/cr-blog/2010/january/diesel-says-be-stupid

Grice’s Cooperative Principle (1976)

Manner

Avoid ambiguity

http://www.brainstorming.ba/?p=99

http://streetstylista-guy.blogspot.com/2010/09/think-less-stupid-more.html

http://melodysnook.wordpress.com/2009/05/

Grice’s Cooperative Principle (1975)

advertising = no “co-operation”

YET

the

interpretation of ads depends

operation”.

on

“co-

We always assume that, however obscure the ad, it

is directed at us, and it can be understood in terms

of:

the

purpose of the advertiser

the direction of the communicative exchange

Grice’s Cooperative Principle (1975)

Copywriters flout at least one maxim.

Why? Because advertisers have to compete for

attention. They have to counter our resistance to direct

selling.

Grice’s Cooperative Principle (1975)

In Britain, at least, violations are typically indirect.

(1)They leave the actual sales pitch to us, as something we (cleverly)

find by noticing the flouted maxim and arriving at the right

implicatures.

(2)We test our interpretation back against what we take to be their

purpose: we reject interpretations that don’t tell us something

favourable about the brand.

Perusasion & Rhetorical tropes

When persuasion is the overriding goal, as in

advert language, the manner in which a statement is

(visually or verbally) expressed is more important

than its content

With rhetorical figures, copywriters look for the

most effective form of expression in swaying the

audience

Rhetorical tropes

Rhetorical tropes are DEVIATION from the expected

norm

When we speak, communication sets up

expectations which function as conventions or

constraints (Grice’s maxims)

Rhetorical tropes

Listeners/viewers are aware of them: indeed words

and images are used to convey one of the main

meanings given in dictionaries

Rhetorical tropes flout these conventions

Rhetorical tropes

Listeners/viewers exactly know what to do when a speaker

flouts a convention: they create an implicature

This means that listeners/viewers search for a context that will

render the flouting intelligible

If context permits an inference, then the consumer will achieve

an understanding of the advertiser’s (visual or verbal)

statement

Rhetorical tropes

Consumers therefore have conventions available to deals with

floutings of convention

When a search for context successfully restores understanding,

the consumer assumes a figurative use and responds accordingly

Because there is a deviation, consumers are invited to translate

the text with one additional meaning

Rhetorical tropes

Consumers are under no compulsion to start reading

a headline or watching a pict, or finish reading it or

continue on to read the rest of the ad.

Therefore, an important function of rhetorical figures

is to motivate the potential consumer.

References

Barthes, Roland. 1977. Image-Music-Text. London: Fontana.

Callow, Michael A. / Schiffman, Leon. 2002. Implicit Meaning in Visual Print Advertisements: A Cross-Cultural Examination of the Contextual Communication

Effect. International Journal of Advertising, 21: 259-277.

Cook, Guy. 1992. The Discourse of Advertising. London: Routledge.

Edens, Kellah M. / McCormick, Chistine B. 2000. How Do Adolescents Process Advertisements? The Influence of Ad Characteristics, Processing Objective, and

Gender. Contemporary Educational Psychology 25: 450-463.

Grice 1976

Goddard, Angela.1998. The Language of Advertising. London: Routledge.

Halliday. M.A.K. 1985. An Introduction to Functional Grammar. Edward Arnold, London.

Kövecses, Zoltan. 2005. Metaphor in Culture. Universality and Variation. Cambridge. Cambridge University Press.

Lakoff, George / Johnson, Michalel. 1980. Metaphor we live by. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Lanham, Richard A. 1969. A Handlist of Rhetorical Terms. Berkeley: University of California Press .

Leech, Geoffrey. 1966. English in Advertising, London: Longman.

McQuarrie, Edward / Mick, David G. 2003. Visual and Verbal Rhetorical Figures under Directed Processing versus Incidental Exposure to Advertising.

Journal of Consumer Research: 579-587.

McQuarrie, Edward / Mick, David G. 1996. Figures of Rhetoric in Advertising Language. Available at http://lsb.scu.edu/~emcquarrie/rhetjcr.htm. Retrieved

on Nov. 18, 2010.

Myers, Greg. 1994. Words in Ads. London: Arnold.

Myers, Greg. 1998. Ad Worlds. London: Arnold.

McQuarrie, Edward F / Mick, David G. 1992. On Resonance: A Critical Pluralistic Inquiry into Advertising Rhetoric. Journal of Consumer Research 19: 180-97.

Pennarola, Cristina. 2009. Nonsense. Deviascion in advertising. Napoli: Liguori