Wed pm Jenny and Matt - University College Cork

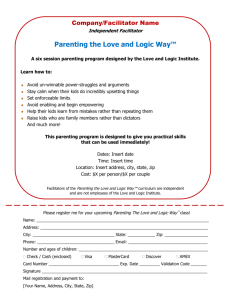

advertisement

Choosing measures and evaluation tools in social intervention Methodologies for a new era summer school School of Applied Social Studies, University College Cork Wednesday 22nd June 2011 Matthew Morton, Jennifer Burton Purposes of Measures Implementation Adherence, quality, responsiveness, exposure Outcome Changes (or baseline screening) in attitudes, behaviors, wellbeing From inputs/Outputs to Outcomes/Impacts Theory of change “Blueprint of the building blocks needed to achieve the long-term goals of a social change initiative.” Informed by… Existing evidence Psychosocial Theory Formative research Stakeholder input Standard results chain Main Components of a Theory of Change Component Description Inputs Resources that go into a project/program (e.g., funding, staffing, equipment, curriculum materials) Activities What we do. Outputs What we produce. Tangible and can be counted. (e.g., # trainings, attendance, partnerships created, quality processes) Outcomes Why we do it. Behavioral/attitudinal changes, result from outputs. (e.g., quit smoking, reduce depression, better parenting) Impacts Long-term changes that result from accumulation of outcomes. Strategic. (e.g., reduce infant mortality) Kusek & Rist 2004 ToC Assumptions • External: The program is feasible, addresses real problems/needs, built on accurate beliefs of human nature, and culturally/politically appropriate. • Internal: The program’s process and implementation will be implemented as intended by the TOC. • Evaluative: The data captures the intended indicators/outcomes and is accessible. The methodology credibly assesses the TOC. Exercise – 1. Topic clusters 1. Children 2. Disabled 3. Discrimination 4. Elderly 5. Environment 6. Health 7. Homelessness 8. Immigration 9. Youth Exercise – Outcomes Mapping 4 months 1 year 5 years Level I (e.g., child) Level II (e.g., family) Level III (e.g., neighborhood) Think: (a) changes, (b) specific, (c) realistic, (d) measureable Types of Measures Strengths Weaknesses Self-report (e.g., q’airre) Relatively easy to implement; helps with feelings/attitudes Self-report biases Third party (e.g., parent, teacher, psychologist) Avoids self-report biases; alternative perspective Limited perspectives; more complicated than self-report to implement Observational (e.g., observer, More objective; less subject to video) participant bias Difficult & costly; harder to standardize coding Institutional data (e.g., school or gov’t records) Can be limited; may not capture important “softer” psychosocial outcomes Often directly policy-relevant; objectivity; can avoid burden of surveys What Makes a Good Measure? • Matches Theory of Change • Appropriate for population (age, culture, language, etc.) • Well-tested • Reliability – The extent to which a test can discriminate between one subject and another • Validity - The extent to which a test measures what is is intended to measure Reliability INTERNAL CONSISTENCY INTER-RATER RELIABILITY TEST-RETEST RELIABILITY Measures level of agreement among individual test items Measures agreement between different raters Measures agreement between successive ratings over time Inter-rater Reliability For continuous variables The Intra-Class Correlation Coefficient (ICC) measures the extent to which overall test variance is attributable to variability between patients as opposed to random error variability (ie signal-tonoise ratio) Inter-rater Reliability For binary (dichotomous variable) Kappa measures the proportion of agreement above that by chance For ordered categorical data, weighted kappa quantifies degree of disagreement Values range 0-1 (1=perfect agreement) 0.4-0.6 = Moderate >0.80 = Very high Internal Consistency Measures the extent to which items of the same scale (or subscale) are inter-correlated Cronbach a increases as (a) average inter-item correlation rises or (b) number of items rises No formal test statistic for a >0.5 = moderate >0.8 = excellent Types of Validity CONTENT (FACE) To what extent do the items reflect the construct being assessed? CRITERION (CONCURRENT) How does the test perform against the ‘gold standard’? CRITERION (PREDICTIVE) Do results on the test predict future outcomes? (i.e., why it’s important) CONSTRUCT Do all the items (in a subscale) relate to the same concept? CONVERGENT Do the test results correlate with those of other theoretically related tests? DIVERGENT Is the correlation low between the test and others which should be unrelated? Benefits of community based parenting groups for hard-to-manage children: Findings from the Family Nurturing Network Trial Jenny Burton Frances Gardner University of Oxford Centre for Evidence Based Intervention Funded by the Esmee Fairbairn Foundation DEMOGRAPHIC INFORMATION Parent How old? Status? Married, living as married, single, divorced etc. Employed? Educational achievement? Child Gender? Age? Siblings? PRIMARY AIMS OF INTERVENTION Parents Help provide parents with necessary skills with which to deal with their hard to manage children Target Child Decrease child negative behaviour eg. Non-compliance, tantrums, yelling,destructive, aggressive behaviours. SECONDARY AIMS OF INTERVENTION Parent Improve sense of parenting competence Improve mood Improve their relationships Worst Sibling Decrease child negative behaviour in other siblings MEASURES USED TO ASSESS PARENT OUTCOME AT BASELINE AND POST INTERVENTION (I) Questionnaires Parenting Scale(Arnold, O’Leary et al, 1993) Beck Depression Inventory (Beck, 1972) Parent Sense of Competence (PSOC; Johnston & Mash, 1989) Dyadic Adjustment Scale (DAS; Spanier, 1976) MEASURES USED TO ASSESS CHILD OUTCOME AT BASELINE AND POST INTERVENTION (II) Parent-report questionnaires: Eyberg Child Behavior Inventory (ECBI; Robinson et al,1980) Parent interview: Semi-structured interview re conduct & hyperactivity: Parent Account of Child Symptoms (PACS; Taylor et al,1986) MEASURES USED TO ASSESS CHILD OUTCOME AT BASELINE AND POST INTERVENTION (III) Teacher Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ, Goodman et al, 1999) WHY USE DIRECT OBSERVATIONS? (I) Direct observations Planning interventions Evaluate outcomes Examine research questions about the mechanisms involved in parent-child interaction WHY USE DIRECT OBSERVATIONS? (II) Provide window on real processes and outcomes of interest, eg. parent skills and strategies and child problem behaviour in the home. Behaviours defined by researcher rather than parent (therefore less easily influenced by parent mood or expectations of intervention) Self-reported outcomes problematic as parents tend to overestimate change following intervention. WHY USE DIRECT OBSERVATIONS? (III) Bias due to expectancy effects less likely (distressed parents poor at manipulating their child into behaving well during home observation) Observational measures can be particularly sensitive to change in parent and child behaviour following intervention Observed behaviour a better predictor of long-term hard outcome measures such as arrest rates and incarceration. DIRECT OBSERVATIONS IN PRACTICE (I) Choose a visit protocol and coding system which address the questions which need answering: Do parents use more positive parenting strategies? Does negative child behaviour decrease? In there an increase in positive interaction between parent and child Do measures assess treatment change or group differences? DIRECT OBSERVATIONS IN PRACTICE (II) Different observational tasks designed to study parent-child interaction in home: Mildly stressful events eg: mealtimes Problem solving tasks and tidy up tasks Tasks where mother busy and child has nothing to do IMPLEMENTATION FIDELITY Exposure (eg. how many sessions) Adherence Quality Reponsiveness (Therapy Attitude Inventory) PARENTING INTERVENTION: THEORY OF CHANGE Inputs • Hire staff • Train staff to implement tested intervention Activities Outputs • Carry out 14 week parenting intervention •Ensure treatment integrity • Maximise parent Participation Outcomes (shortterm) • Decreased child negative behaviour • Increased parenting skills and strategies Outcomes (long-term) • Less delinquency • Less incarceration PARENTING INTERVENTION: THEORY OF CHANGE Inputs • Hire staff • Train staff to implement tested intervention Activities Outputs • Carry out 14 week parenting intervention •Ensure treatment integrity • Maximise parent Participation Outcomes (shortterm) • Decreased child negative behaviour • Increased parenting skills and strategies Outcomes (long-term) • Less delinquency • Less incarceration Exercise 2 - ToC • Construct a basic TOC of an intervention you’ve worked with/have interest in, and focus on key outcomes • Identify potential measures or types of measures for implementation and outcomes that match your ToC Example TOC template Youth Program Assessment Tools Implementation Guide to various instruments for Measuring Youth Program Quality by the Forum for Youth Investment http://forumfyi.org/content/measuring-youth-program-quality-guideassessment-tools-2nd-edition l E.g., Youth Program Quality Assessment (PQA) Outcomes CART: Compendium of various psychosocial measures (esp., for youth) http://cart.rmcdenver.com/index.cgi?screenid=seldomain&autoid=91867 CORC: http://www.corc.uk.net/index.php?contentkey=81 Select references Church, A. T. (2010). Measurement Issues in Cross-cultural Research. In G. Walford, E. Tucker & M. Viswanathan (Eds.), The Sage Handbook of Measurement (pp. 152-175). London: SAGE. (validity across cultures) Streiner, D. L. (2003). Starting at the Beginning: An Introduction to Coefficient Alpha and Internal Consistency. Journal of Personality Assessment, 80(1), 99103. Imas, L. G. M., & Rist, R. C. (2009). The Road to Results: Designing and Conducting Effective Development Evaluations. Washington, D.C.: The World Bank. (fesp. for Th of Chg) Weiss, C. H. (1995). Nothing as Practical as Good Theory: Exploring Theorybased Evaluation for Comprehensive Community Initiatives for Children and Families. In J. P. Connell, A. C. Kubisch, L. B. Schorr & C. H. Weiss (Eds.), New Approaches to Evaluating Community Initiatives: Concepts, Methods, and Contexts. Washington, DC: Aspen Institute. 4.2. Questscope Non-Formal Education Theory of Change INPUTS Participatory methodology • Flexible curriculum • Questscope training & support on empowerment Supportive adults • Trained professional facilitators ACTIVITIES OUTPUTS Social/ developmental • Facilitate participatory strengths-building activities (e.g., leadership games; sports, cultural, & vocational activities; camps and experiential trips) Exposure • 2+ days per week youth attendance, approx. 3 hours per day Physical center • Comfortable, changeable space designated for NFE Involve youth in decision-making processes Funding • Ministry of Education funding of space & facilitators • Questscope grants & donations for quality assurance and programming Learning • Facilitate dialoguebased participatory lessons in curriculum areas (e.g., math, Arabic, English, religion, science) ASSUMPTIONS Responsiveness • Youth feel empowered & engaged in program Prosocial environment • Safe, positive setting, including supportive social facilitator-youth & youth-youth interactions PROXIMAL OUTCOMES DISTAL OUTCOMES Increased... Increased... Developmental assets • Self-efficacy • Prosocial behavior • Social supports (friends, family, local adults) • Social skills Social inclusion • Integration into formal education, vocational training, and/or stable employment Literacy & academic ability Decreased... Behavioral difficulties • e.g., Conduct problems, peer problems Civic engagement • community & democratic participation Long-term impact • Contributions to improved family, community, and society level indicators (e.g., economic & health) 1. The policy and funding context is amenable to quality implementation. 2. Youth empowerment is culturally acceptable among key stakeholder groups. 3. Empowerment-based programming can attract, retain, and engage participants. 4. The program can change outcomes with a particularly marginalized population.