Functional Basis of Intelligence

advertisement

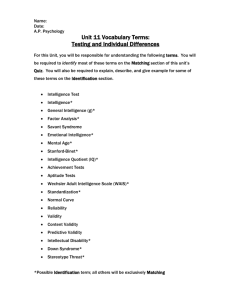

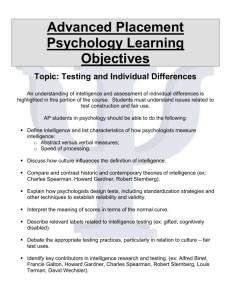

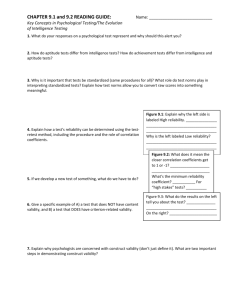

Functional Basis of Intelligence Intelligence • One enduring problem has been our definition of intelligence, which has undergone various changes. Today intelligence is commonly defined as the capacity to learn from experience and to adapt to new situations. This approach has the advantage of being applicable at various phylogenetic levels, but it does not show the complexity of our current views. • First, there is the question of measuring intelligence, a bold idea at its inception early in this century and still disputed today. Second, people with exceptional intelligence pose a special problem. A Three-Dimensional Model • The most comprehensive multifactor theory to dateconsiders intellectual ability in terms of three dimensions: how information is processed, which is called operations; what information is involved, which is called contents; and the results, which are called products. These dimensions are subdivided into five, four, and six parts, respectively, making a cubic model with 120 elements. These 120 potential intellectual abilities define the structure-of-intellect (SI) model. • The operations dimension has been discussed indirectly in the chapters on cognition and memory. More than the others, it concerns specific mental functions. One operation, for example, is memory, which involves the storage and retrieval of information. Another is convergent thinking, in which stored information is used in a search for one particular answer to a problem. Islands of genius: Savant syndrome • After a 30-minute helicopter ride and a visit to the top of a skyscraper, British savant artist Stephen Wiltshire began seven days of drawing that reproduced the Tokyo skyline. Nonintellectual Factors • Nonintellectual factors, such as persistence, goal awareness, and a concern with social values, have been stressed as well. Motivation and objectives may be considered part of one's intellectual functioning, together with the ability to perceive, memorize, think abstractly, and so forth. • Intelligence, according to this view, is not only rational and purposeful but also worthwhile. A value judgment is fundamentally involved, as it is in our definition of almost any abstract concept. This approach extends the concept of intelligence a great deal, perhaps beyond the point at which it continues to be useful. Intelligence and Creativity • Expertise, a well-developed base of knowledge, furnishes the ideas, images, and phrases we use as mental building blocks. • . Imaginative thinking skills provide the ability to see things in novel ways, to recognize patterns, and to make connections. Having mastered a problem’s basic elements, we redefine or explore it in a new way. • A venturesome personality seeks new experiences, tolerates ambiguity and risk, and perseveres in overcoming obstacles. • Intrinsic motivation is being driven more by interest, satisfaction, and challenge than by external pressures. • A creative environment sparks, supports, and refines creative ideas. Emotional Intelligence • Emotional intelligence is the ability to perceive, understand, manage, and use emotions. Those with higher emotional intelligence achieve greater personal and professional success. However, critics question whether we stretch the idea of intelligence too far when we apply it to emotions. • The social intelligence have called by John Mayer, Peter Salovey, and David Caruso as emotional intelligence. Spatial intelligence genius • In 1998, World Checkers Champion Ron “Suki” King of Barbados set a new record by simultaneously playing 385 players in 3 hours and 44 minutes. • Thus, while his opponents often had hours to plot their game moves, King could only devote about 35 seconds to each game. Yet he still managed to win all 385 games! Emotional intelligence components • perceive emotions (to recognize them in faces, music, and stories). • understand emotions (to predict them and how they change and blend). • manage emotions (to know how to express them in varied situations). • use emotions to enable adaptive or creative thinking. The Origins of Intelligence Testing • In France in 1904, Alfred Binet started the modern intelligencetesting movement by developing questions that helped predict children’s future progress in the Paris school system. Lewis Terman of Stanford University revised Binet’s work for use in the United States. Terman believed his Stanford-Binet could help guide people toward appropriate opportunities, but more than Binet, he believed intelligence is inherited. • During the early part of the twentieth century, intelligence tests were sometimes used to “document” scientists’ assumptions about the innate inferiority of certain ethnic and immigrant groups. Smart and rich? • Jay Zagorsky (2007) tracked 7403 participants in the U.S. National Longitudinal Survey of Youth across 25 years. • As shown in this scatterplot, their intelligence scores correlated +.30 with their later income. Alfred Binet: Predicting School Achievement • Binet personally leaned toward an environmental explanation. To raise the capacities of low-scoring children, he recommended “mental orthopedics” that would train them to develop their attention span and selfdiscipline. He believed his intelligence test did not measure inborn intelligence as a meter stick measures height. • Rather, it had a single practical purpose: to identify French schoolchildren needing special attention. Binet hoped his test would be used to improve children’s education, but he also feared it would be used to label children and limit their opportunities. Lewis Terman: The Innate IQ • From such tests, German psychologist William Stern derived the famous intelligence quotient, or IQ. The IQ was simply a person’s mental age divided by chronological age and multiplied by 100 to get rid of the decimal point: • IQ = (mental age/chronological age) x100 • Thus, an average child, whose mental and chronological ages are the same, has an IQ of 100. But an 8-year-old who answers questions as would a typical 10-year-old has an IQ of 125. Intelligence testing • Terman promoted the widespread use of intelligence testing. His motive was to “take account of the inequalities of children in original endowment” by assessing their “vocational fitness.” • In sympathy with eugenics—a much-criticized nineteenthcentury movement that proposed measuring human traits and using the results to encourage only smart and fit people to reproduce— Terman envisioned that the use of intelligence tests would “ultimately result in curtailing the reproduction of feeble-mindedness and in the elimination of an enormous amount of crime, pauperism, and industrial inefficiency”. Street smarts • This child selling candy on the streets of Manaus, Brazil, is developing practical intelligence at a very young age. Modern Tests of Mental Abilities • Psychologists classify such tests as either achievement tests, intended to reflect what you have learned, or aptitude tests, intended to predict your ability to learn a new skill. Exams covering what you have learned in this course are achievement tests. • A college entrance exam, which seeks to predict your ability to do college work, is an aptitude test—a “thinly disguised intelligence test,” says Howard Gardner. Aptitude tests • Aptitude tests aim to predict how well a test-taker will perform in a given situation. So they are necessarily “biased” in the sense that they are sensitive to performance differences caused by cultural experience. But bias can also mean what psychologists commonly mean by the term—that a test predicts less accurately for one group than for another. In this sense of the term, most experts consider the major aptitude tests unbiased. • Stereotype threat, a self-confirming concern that one will be evaluated based on a negative stereotype, affects performance on all kinds of tests. Psychologist David Wechsler • Psychologist David Wechsler created what is now the most widely used intelligence test, the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS), with a version for school-age children (the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children [WISC]), and another for preschool children. As illustrated in FIGURE 10.5, the WAIS consists of 11 subtests broken into verbal and performance areas. • It yields not only an overall intelligence score, as does the Stanford-Binet, but also separate scores for verbal comprehension, perceptual organization, working memory, and processing speed. Gray matter matters • A frontal view of the brain shows some of the areas where gray matter is concentrated in people with high intelligence scores, and where g may therefore be concentrated. Flexibility or versatility of adjustment • Intelligence is difficult to define, but most definitions generally refer to some aspect of flexibility or versatility of adjustment. Its measurement is often accomplished by individual intelligence tests: the StanfordBinet, from which the concept of mental age (MA) and the intelligence quotient (IQ) developed; and the Wechsler Scales, which feature a wide variety of subtests with both verbal and non-verbal items. Alfred Binet • “Some recent philosophers have given their moral approval to the deplorable verdict that an individual’s intelligence is a fixed quantity, one which cannot be augmented. We must protest and act against this brutal pessimism” Standardization • The number of questions you answer correctly on an intelligence test would tell us almost nothing. To evaluate your performance, we need a basis for comparing it with others’ performance. To enable meaningful comparisons, test-makers first give the test to a representative sample of people. • When you later take the test following the same procedures, your scores can be compared with the sample’s scores to determine your position relative to others. This process of defining meaningful scores relative to a pretested group is called standardization. Matching patterns • Block design puzzles test the ability to analyze patterns. • Wechsler’s individually administered intelligence test comes in forms suited for adults (WAIS) and children (WISC). Intelligence and Personal Factors • In cross-sectional investigations, different subjects are studied at different ages. In the longitudinal method, the same subjects are studied as they grow older. • Cultural change is an additional influence in both approaches, and when control procedures are used to correct for cultural improvements, it is found that mental growth continues into the fifth decade and later, providing that the individual is engaged in stimulating mental activities. The highest levels of performance for the different mental abilities are reached at different ages. Exceptional Intelligence • Mentally gifted persons comprise the upper 2 percent of the population in mental ability, and generally they are more physically fit, socially adept, and traditionally moral than the general population. Educational programs for the gifted are less structured and proceed more rapidiy than those for other children. • They also stress research skills and originality; these goals are achieved partly by permitting such students to work together on a multigrade basis. Close cousins: Aptitude and intelligence scores • A scatterplot shows the close correlation between intelligence scores and verbal and quantitative SAT scores. Origins of Intelligence • The nature-nurture controversy has a long history, extending through many studies of national and racial differences. The question of the genetic basis of group differences is impossible to answer for several reasons, chiefly the absence of satisfactory tests and the difficulty in establishing appropriate samples of subjects. • The most promising research on the origins of intelligence involves comparison of identical twins reared apart, but even these investigations afford diverse interpretations. The influences of heredity and environment are always present and they depend upon one another. The significant issue is to understand their interaction in the production of intelligence. Males and females average • Males and females average the same in overall intelligence. There are, however, some small but intriguing gender differences in specific abilities. Girls are better spellers, more verbally fluent, better at locating objects, better at detecting emotions, and more sensitive to touch, taste, and color. • Boys outperform girls at spatial ability and related mathematics, though girls outperform boys in math computation. Boys also outnumber girls at the low and high extremes of mental abilities. Psychologists debate evolutionary, brain-based, and cultural explanations of such gender differences. The normal curve • Scores on aptitude tests tend to form a normal, or bellshaped, curve around an average score. • For the Wechsler scale, for example, the average score is 100.