- White Rose Etheses Online

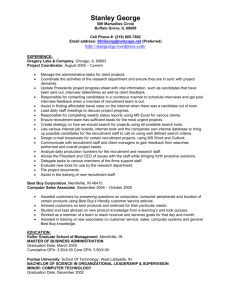

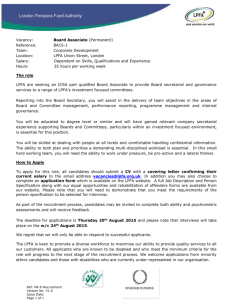

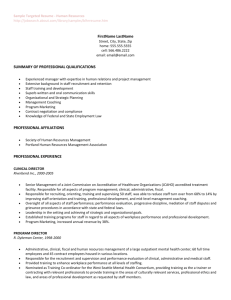

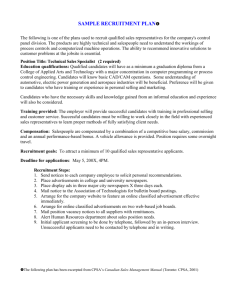

advertisement