about In-text Citations

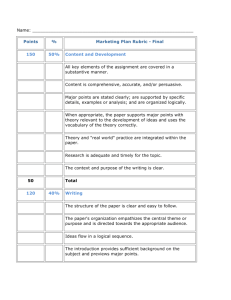

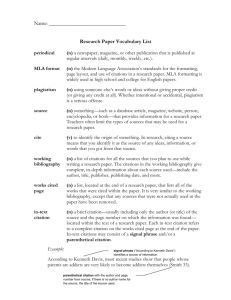

advertisement

I not only use all the brains that I have, but all that I can borrow. —Woodrow Wilson An Introduction to Documentation, In-text Citations, and Framing ENL 111, Dr. Vavra What IS “Documentation”? “Documentation” denotes various formats for indicating in your writing where your source materials (articles, books, interviews, web pages, etc.) come from. In other words, “documentation” enables readers of your writing to find your sources. The Purposes of Documentation Documentation has four primary purposes, one negative, and three positive: To avoid plagiarism, To give credit where it is due, To enable readers to find your sources, and To add to your own credibility. The Formats of Documentation We live in a free country. As a result, there is no one who can tell us the one right way to format documentation. As a result, there are several different formats for documenting sources. (Don’t complain. If we want freedom, we need to pay for it.) Formats for Documentation - 1 MLA (from the Modern Language Association) APA (from the American Psychological Association) Various formats in databases Formats for Documentation - 2 We will be using the MLA format. In some courses you will be expected to use APA, but the differences between the two are mainly questions of what information goes where in the format. (We may look at the differences in a later class.) The Three Parts of Documentation Works Cited (and/or) Bibliography In-text citations Framing Works Cited or Bibliography? A “Works Cited” is an alphabetical list of all the sources (works) that you cited (used) in your paper. A “Bibliography” usually includes everything in the Works Cited, but also includes other sources that the writer believes are relevant to the topic. Your “Works Cited” List For Major Paper 2, I have given you the citations for your MLA “Works Cited” list in the notes to each of the four essays. Two of those entries are: Perry, William G. “Examsmanship and the Liberal Arts.” Harvard University/Samuel Lipoff. n.d. Web. 23 June 2012. Twain, Mark. “Corn-pone Opinions.” Famous American Essays. Ed. John J. Public. New York: Classic Books, Inc., 1954. 154-157. Print. Your “Works Cited” List Note that a “Works Cited” list should be in alphabetical order. If a source has no author, use the first words in the entry (such as the title of the article). Do NOT use “Anonymous.” If an entry begins with “A,” “An,” or “The,” ignore these words and use the second word in the entry. The Parts of a Works Cited Citation We will be working on making “Works Cited” lists later in this course. For this paper, you already have what you need. Here we will concentrate on in-text citations and framing. In-text Citations Your Works Cited tells your readers what sources you used, but it does not tell them where specific information in your paper came from. To do that, you need to include citations in your text – they are called “in-text” citations. An In-text Citation Suppose that the following were in a paragraph in a paper: Jennifer Crocker, a professor of psychology at Michigan, suggested that “In some cases, having an incremental theory might actually lead to dysfunctional behavior.” (Glenn 7). In-text citations go in parentheses right after the end of the source material. An In-text Citation Jennifer Crocker, a professor of psychology at Michigan, suggested that “In some cases, having an incremental theory might actually lead to dysfunctional behavior.” (Glenn 7). In-text citations should include just enough information to find the source in your Works Cited list, plus the page number on which that information is located. [Memorize this!] Thus, this citation directs us to find the source by Glenn in the Works Cited list. It also tells us that once we find that source, the given information is on page seven. Page Numbers in In-text Citation The only cases in which you do not need a page number are those in which the source is entirely on one page. (That information will be on the Works Cited list.) For our purposes, if any other source does not have page numbers (such as web pages) number the pages of your print-out and use those page numbers. Source Markers in In-text Citations If it is not indicated by a voice marker (which we will get to), the in-text citation should include the first words of the “Works Cited” entry for that source, plus the page number on which that information is found. For example – (Perry 36). Source Markers in In-text Citations A “voice marker” is a word or phrase that indicates the source of the information. If you use one, you just need the page number. For example: According to William Perry, a “cow” is a person who just spits back facts. (36) This format means that there is a source in the “Works Cited” that starts with “Perry.” Thus “Perry” does not need to be repeated in the in-text citation. Paraphrasing vs. Quoting Note, by the way, that you need documentation for ideas, etc., not just for material that you quote. As far as documentation is concerned paraphrases and quotations are treated in the same way. Framing Sources You will be learning more about framing sources in the chapters that will be assigned from They Say / I Say. The following is a preview. It is called “framing” because it consists of putting two pieces of information before, and two after, any source materials that you use. Framing Sources Four things are involved in framing: 1. Voice Marker 2. Credibility Marker <source material (quoted or paraphrased)> 3. In-text Citation 4. Metacommentary Voice Markers - 1 We have already briefly discussed voice markers. Graff and Birkenstein give a number of good templates for them, and they also provide a nice list of verbs that can be used in place of “said.” Voice Markers - 2 Remember that the first time you name a source, use their first and last name. After that, use only their last name. The first time you mention him, use “Mark Twain.” After that, use “Twain.” (I do NOT want to see “Mark” unless you want a big hole in your gas tank.) Credibility Markers - 1 As their name suggests, credibility markers provide information about the credibility of the source. This may be biographical information, such as: The famous philosopher William James claims that . . . . Dr. Mark Noe, an English professor at Penn College, has written that . . . . Credibility Markers - 2 In other cases, you can use the place of publication as a credibility marker: In an article in the National Review online, Rich Lowry claims that . . . . “Dirty Laundry Reloaded into your washingmachine,” a feature story on the Greenpeace International web site, argues that . . . . Credibility Markers - 3 Later in the course, you may find that if you examine your sources, they will give you information about the author, either before or after the article itself. Credibility Markers - 4 For MP # 2, you can get two bonus point for including credibility markers for each of the three authors that you use, for a total of six points. Note that you only include the credibility marker in the frame the first time that you use the source. In-text Citations as Voice Markers In-text citations also serve the purpose of voice markers. They indicate the end of the “voice” of the source, thereby returning responsibility for the ideas to the writer (you). Metacommentary - 1 You will already have read and discussed all four essays before the Chapter Ten on metacommentary is assigned, but you might want to browse it sooner. (It’s eight pages, but very important.) Metacommentary - 2 Metacommentary comes after the in-text citation. As Graff and Birkenstein nicely explain, metacommentary can do many things. The most important thing that it does, however, is to show that you (the writer) are thinking. Metacommentary - 3 Metacommentary can, among other things: Explain what you think the source material means. Explain how it relates to your thesis. Explain why you agree, disagree, or both with the ideas expressed by the source. Metacommentary - 4 For MP # 2, you can get two bonus point for including metacommentary for each of the three authors that you use, for a total of six points. See Graff and Birkenstein for templates on how to introduce metacommentary. A Suggestion (1) Always make your Works Cited list before you begin to draft a paper. That way you will know exactly what you are going to cite. As you write your draft of a paper, include the in-text citations in the draft. A Suggestion (2) Far too many students do not do this. Then they can’t find the sources when they go back to “revise” the paper. The result is that they end up with a serious plagiarism problem. (Remember that part of my job is to check your citations against the copies of your sources that you will be giving me.) Quiz (You can use your notes.) 1. What are the four purposes of documentation? (10 each) 2. What are the two purposes of an in-text citation? (10 each) 3. In MLA format, what is the general rule for what goes in the in-text citations? (40) A noted psychiatrist was a guest at a National Organization for Women gathering, and his hostess naturally broached the subject in which the doctor was most at ease. "Would you mind telling me, Doctor," she asked, "how you detect whether or not an individual is mentally challenged who appears to be completely normal?" "Nothing is easier," he replied. "You ask them a simple question which everyone should answer with no trouble. If they hesitate, that puts you on the track." "What sort of question?" "Well, you might ask them, 'Captain Cook made three trips around the world and died during one of them. Which one?'" The woman thought a moment, then said with a nervous laugh, "You wouldn't happen to have another example, would you? I must confess I don't know much about history."