Part 2

advertisement

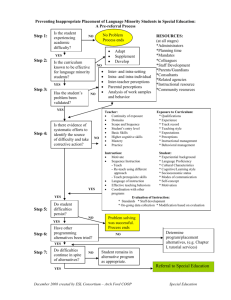

Part 2 The PIC Model: The Role of Counselors PIC provides a framework for a dynamic and interactive process which emphasizes career counselors’ role as decision counselors, whose aim is to facilitate an active decision-making process. The 3 Roles of Career Counselors Discover what stage of the career-decision making process the individual is in currently. Review the individual’s previous career decisionmaking stage(s), and, if needed, repeat one or more of them. Guide the clients through the remaining stages. -- Thus, the model’s components can be adapted according to the counselee’s style and needs, and the counselor’s judgment. All three stages of the PIC have the similar underlying structure of a dynamic counselor-client dialogue: First, the counselor presents the goal of the stage and the client’s expected role in it. Second, the client actively participates by providing answers to questions presented by the counselor. The counselor uses his or her expertise and impression of the client’s unique personality and abilities to monitor the adequacy of the client’s responses. Third, the counselor discusses with the client what occurred in the second phase and the outcomes. Before Beginning the Decision-Making Process: Assessing the Client’s Readiness 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Evaluating the client’s general level of career indecision (e.g., Career Decision Scale), Examining his or her specific difficulties in reaching a decision (e.g., the Career Decision-making Difficulties Questionnaire) Assessing career choice anxiety (e.g., Career Factors Inventory) Discovering dysfunctional thinking patterns in career problem-solving and decision-making (e.g., the Career Thoughts Inventory) Identifying dysfunctional beliefs (e.g., the Career Beliefs Inventory). Career Decision-Making Difficulties The first step in helping individuals is to locate the focuses of the difficulties they face in making career decisions Gati, Krausz, and Osipow (1996) proposed a taxonomy for describing the difficulties (see Figure 1) Figure 1: Locating Career Decision-making Difficulties based on the taxonomy of Gati, Krausz, & Osipow (1996) During the Process Prior to Engaging in the Process Lack of Readiness due to Lack of Indecimotivation siveness Lack of Information about Dysfunc- Cdm Self Occupations tional process beliefs Ways of obtaining info. Inconsistent Information due to Unreliable Internal Info. conflicts External conflicts The Career Decision-making Difficulties Questionnaire (CDDQ) The Career Decision-making Difficulties Questionnaire (CDDQ) was developed to test this taxonomy and serve as a means for assessing individuals’ career decisionmaking difficulties Cronbach Alpha internal consistency estimates: .70-.90 for the 3 major categories, .95 for the total CDDQ score Empirical Structure of the Difficulties (N= 10,000; 2004) Lack of motivations Indecisiveness Dysfunctional beliefs Lack of info about self Lack of info about process LoI about occupations LoI about addition sources of help Unreliable Information Internal conflicts External conflicts Computerized Assessment of Career Decision-Making Difficulties The CDDQ was incorporated into a careerrelated self-help-oriented free of charge Internet site (www.cddq.org). Research has shown that the Internet and the paper-and-pencil versions of the CDDQ are equivalent (Gati & Saka, 2001; Kleiman & Gati, 2004). The CDDQ was found suitable for different countries and cultures and has been translated into 18 languages. Increasing the Client’s Readiness Dealing with general indecisiveness. Indecisiveness is a generalized inability to make decisions. If the client’s degree of indecisiveness appears to require a more intense and longer intervention, the client should be referred to relevant clinical counseling. Dismantling dysfunctional beliefs and thoughts. Beliefs such as “There is a perfect occupation for me” or “The counselor will find me the right occupation” may impede the decision-making process and lead to less than optimal career-counseling outcomes. It is therefore important to elicit and locate the client’s dysfunctional beliefs and dismantle them as part of the preparation phase. Explaining the steps of the decision-making process to the client. This includes explaining the basic rationale behind the systematic procedure and its advantages over a haphazard choice, describing the three stages of the PIC model, and discussing each stage’s goal, process, and expected outcome. (1)Prescreening the Potential Alternatives (a) locating the career-related aspects that are most important to the client: Clients can construct a list of relevant aspects by themselves, based on their life experience and aspirations. The client’s more important aspects can be elicited using Kelly’s repertory grid or using Tyler’s Vocational Card Sort Counselors can facilitate this step also by presenting the client with a list of the potentially relevant aspects (1)Prescreening the Potential Alternatives (b) ranking the selected aspects by importance To help the client create a rank-order of aspects, the counselor might ask guiding questions, such as: “You said that ‘independence’ is the most important aspect for you. What aspect would you regard as second in importance?” (1)Prescreening the Potential Alternatives (c) defining the compromise range for each of the selected aspects The counselor is expected to encourage the client to locate and report his or her optimal preferences, yet also to consider compromising on within-aspect levels. For example: “You said that for the aspect ‘length of training’ your optimal level would be a 2-year college program. Would you be willing to compromise and regard a 4-year college program as acceptable as well?” (1)Prescreening the Potential Alternatives (d) Sequential Elimination: comparing the individual’s preferences with the alternatives’ characteristics Provide the client with feedback, including examples of the eliminated options in each aspect. For example: “With respect to the aspect ‘length of training’, the following occupations are incompatible with your preference for a 2-year or 4-year college program: medicine, psychology, law ...”. Using computerized systems such as CHOICES, DISCOVER, and MBCD (Making Better Career Decisions (http://mbcd.intocareers.org) can help provide such feedback. (1)Prescreening the Potential Alternatives (e) Testing the sensitivity of the results to possible changes in preferences Checking whether the reported preferences still seem acceptable: “Are you certain that you are not willing to consider graduate studies?” Understanding why certain alternatives, which were considered intuitively appealing by the client before the systematic search, were eliminated: “High-school teaching was eliminated from your list because it is incompatible with your preferences for a very high income, high flexibility in working hours, and short training.” Locating alternatives that are ‘almost promising’ – examining the validity of the information about the critical aspect and considering the possibility of compromising in that aspect: “Your wish to use only ‘high artistic ability’ at work led to the elimination of several occupations which are compatible with your preferences in all the other important aspects. Would you like to also consider occupations requiring moderate artistic ability, while expressing your artistic skills in avocational activities?” (1)Prescreening the Potential Alternatives Helping explicating preferences If at any point during the prescreening the client has difficulties in explicating his or her preferences, the counselor can help by directing the client to relevant past experiences and the client’s emotional reactions to those experiences For example, if the client is unsure whether “teamwork” is an important aspect for her, or how willing she is to compromise on this aspect, the counselor may help elicit memories of participation on school committees or in youth organizations, and the emotions associated with them. (2) In-depth Exploration of the Promising Alternatives Verify compatibility of the alternative with the client’s preferences in the most important aspects (e.g., a person who works in one of the considered occupations may mention that she is given much independence in choosing both “what to do” and “how to do it”) Consider the compatibility of the alternative with the client’s preferences in the less important aspects as well. The client may consider going through the prescreening process again, based on revised preferences See whether he or she is willing to meet the requirements specified by the core aspects Examine the probability of actualizing the alternative, explore possible ways of increasing the probability of actualizing certain promising alternatives with the counselor (3) Choosing the Most Suitable Alternative (a) Comparing and evaluating the suitable alternatives clients can make approximate, “local” comparisons of the various alternatives’ advantages by combining some characteristics of one alternative that are equivalent to some combination of characteristics of the other. For example, the advantage of alternative x over y in terms of expected higher income may be roughly equivalent to the advantage of alternative y in terms of better work environment and higher variety. (b) Selecting additional suitable alternatives (3) Choosing the Most Suitable Alternative (c) Reflecting on the decision-making process. The implementation of the decision is liable to be delayed or avoided if the client does not truly feel certain in the decision. Counselors can help clients locate the source of their lack of confidence and discrepancies between intuition and systematic processing, and then either confirm their decision or reach a different one. If the counselor feels that the systematic process has led to an optimal decision, but various emotional factors (e.g., fear of commitment, anxiety, low self-esteem, lack of motivation etc.) deter the client from following through with implementation, the client and counselor should engage collaboratively in cognitive restructuring, affective regulation and stress management. (4) Completing the Decision-Making Process: Implementing the steps that need to be carried out in order to actualize the client’s chosen alternative Identifying the Client’s Stage in the Process It is possible to start the PIC process from “the middle” – according to the client’s needs However, it is recommended to start the process from the beginning, in order to: Strengthen confidence in the occupational alternatives considered by the client Eliminate inadequate alternatives considered by the client Offer additional alternatives that were not considered by the client so far Teach decisions skills: aspect-based instead of occupation-based approach Concluding Remarks The PIC model is flexible and dynamic: it allows clients to move back and forth in the decisionmaking process The PIC model constitutes a framework for a decision-making process that allows clients to play not only an active role but a leading one Informal reports of career counselors suggest that they often, implicitly and intuitively, use a PIC-like, three-stage approach in relevant career counseling cases Still… Career decision-making requires collecting a vast amount of information Complex information-processing is needed But luckily, information and communication technologies are available More and more career counselors incorporate the use of one or more Computer-Assisted Career Guidance Systems, or an Internet version of such systems, into the face-to-face career counseling process The use of an Internet-based career-guidance system for the clinical implementation of the PIC model will be demonstrated in the next part of the workshop