Internship Handbook 6th Edition - University of Illinois Springfield

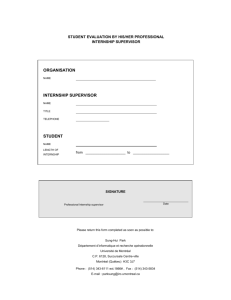

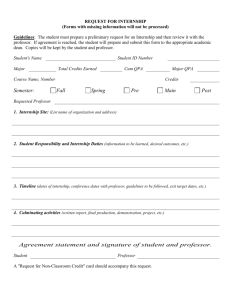

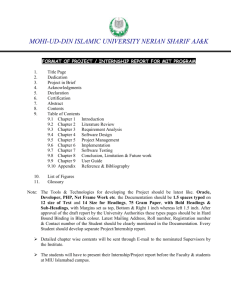

advertisement