ADHD Presentation

advertisement

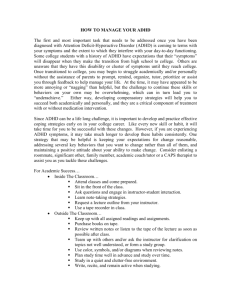

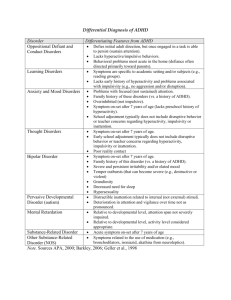

Attention Deficit/ Hyperactivity Disorder: a general overview and classroom strategies for teachers Reuben Pringle & Ryan Abraham General Overview • • • • • ADHD is a neurobiological disorder. As defined in the fourth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (American Psychiatric Association, 1994), there are three subtypes of ADHD: 1. Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder, Predominantly Inattentive Type. 2. Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder, Predominantly Hyperactive-Impulsive Type. 3. Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder, Combined Type. • Within the DSM IV manual there is no medical or scientific term called ADD. Diagnostic Criteria • Diagnostic criteria as mentioned in the New Zealand Guidelines for the Assessment and Treatment of Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (Ministry of Health, 2001): – – – – – • • • The relevant DSM-IV criteria must be present for a diagnosis of ADHD. Children receive a diagnosis if they have core symptoms of either attention problems or hyperactivity/impulsiveness, or both (See next slide for DSM criteria). Symptoms are present in more than one setting, such as home and school, or with more than one caregiver, such as parents and grandparents. Symptoms result in significant impairment. The core problems have been present for at least six months - though in the vast majority of instances they have been present since the first years of life. The problems have begun before the age of seven years of age. A behavioural rating scale that has good reliability and validity should be administered as part of a comprehensive assessment. It is essential to examine for and rule out other psychiatric disorders before a diagnosis of ADHD is made. DSM-IV lists certain conditions (For example, psychosis and Pervasive Developmental Disorders) that need to be excluded. A comprehensive assessment therefore requires routine screening for these conditions to rule out differential diagnoses. The Mental Health Commission has developed a specialist mental health assessment tool for children and young people. This tool is available to child and adolescent mental health services in New Zealand to assist with a comprehensive mental health assessment. DSM-IV Diagnostic Criteria for Attention-Deficit/ Hyperactivity Disorder (American Psychiatric Association, 1994): Criteria: One of the following two criteria must be met. • A1 Six (or more) symptoms of inattention (see below) have persisted for at least six months to a degree that is maladaptive and inconsistent with developmental level. • A2 Six (or more) symptoms of hyperactivity/impulsivity (see below) have persisted for at least six months to a degree that is maladaptive and inconsistent with developmental level. In addition to A1 or A2 above, the following criteria (B–E) must also be met. • B Some inattention or hyperactivity/impulsivity symptoms were present before age seven years. • C Some impairment from the symptoms is present in two or more settings (eg, at school (or work) or at home). • D There must be clear evidence of clinically significant impairment in social, academic or occupational functioning. • E The symptoms do not occur exclusively during the course of a pervasive development disorder, schizophrenia, or other psychotic disorder and are not better explained by another mental disorder, for example, mood disorder, anxiety disorder and dissociative disorder, or a personality disorder. DSM-IV Diagnostic Criteria for Attention-Deficit/ Hyperactivity Disorder (Continued): Inattention items: • Often fails to give close attention to details or makes careless mistakes in schoolwork, work or other activities. • Often has difficulty in sustaining attention in tasks or play activities. • Often does not seem to listen when spoken to directly. • Often does not follow through on instructions and fails to finish schoolwork, chores or duties in the workplace (not due to oppositional behaviour or failure to understand instructions). • Often has difficulty organising tasks or activities. • Often avoids, dislikes, or is reluctant to engage in tasks that require sustained mental effort (e.g. schoolwork or homework). • Often loses things necessary for tasks or activities (e.g. toys, school assignments, pencils, books or tools). • Often is easily distracted by extraneous stimuli. • Often is forgetful in daily activities. Hyperactivity items: • Often fidgets with hands or feet or squirms in seat. • Often leaves seat in classroom or in other situations where remaining seated is expected. • Often runs about or climbs excessively in situations where it is inappropriate (in adolescents or adults, may be limited to feelings of subjective restlessness). • Often has difficulty in playing or engaging in leisure activities quietly. • Often is ‘on the go’ or acts as ‘if driven by a motor’. • Often talks excessively. Impulsivity items: • Often blurts out answers before questions have been completed. • Often has difficulty awaiting turn. • Often interrupts or intrudes on others (e.g. butts into conversations or games). Comorbidity • When treatment and assessment of ADHD is being explored, the identification of any comorbid psychiatric disorders is extremely important as the management strategies can largely differ. Alternate diagnosis-specific guidelines need to be explored if any comorbid disorders are present. The American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry is a good example of this. Green et al (1999) shows in their review how common comorbidity is being: • • • • • Roughly one-third qualified for a diagnosis of oppositional defiant disorder. One-quarter qualified for a diagnosis of conduct disorder. Nearly one-fifth had a depressive disorder. Over one-quarter had an anxiety disorder. Nearly one-third had more than one comorbid condition. Prevalence • • • • • • ADHD is one of the most common behavioural disorders in children. It is 3-4 times more common in boys than in girls. 3-7% of school-aged children are affected by ADHD. ADHD accounts for 30-50% of childhood mental health referrals. There is a much higher prevalence of ADHD in school-aged children than in older age groups. Across the age groups, the prevalence of ADHD decreases as age increases. 50% of those identified with ADHD in childhood continue to display ADHD symptoms in adulthood. (Healey, 2012) • Some students do “grow out of it” i.e. no longer meet the criteria for impairment, but they usually will still show ADHD tendencies. • There is a developmental trend that as age increases hyperactivity aspects will decrease but inattention aspects will increase. (Healey, 2012) • • • • • • • • • Motor Hyperactivity Low Frustration Tolerance Impulsiveness Easily Distracted Inattentiveness Shifts Activities Easily Bored Impatient Restlessness Children Adults Difficulties in the Classroom • • ADHD is associated with difficulties in behavioural, cognitive, social and emotional functioning and for students diagnosed with the disorder this can result in a number of difficulties in the classroom. (Barkley, 1997) Behaviours that teachers might notice include: • • • • • Not listening/ paying attention. Not completing class work. Being irritable and argumentative. Sleeping in class due to lack of restful sleep at night. Academically for students this can result in: • • • • • Having difficulty comprehending what they read. Being unable to memorize isolated facts. Having trouble organizing their thoughts (problematic for writing). Having difficulty holding facts in their heads while working on a maths problem. Difficulty in quickly retrieving information from stored memory. • (Dendy 2000) Obvious and Not So Obvious Behaviours • Students diagnosed with ADHD will face a number of behavioural issues, some more obvious than others. The more obvious behaviours include: • Hyperactivity – – – – • Impulsivity – – – – – • Restless. Fidgets. Can’t sit still. Runs and climbs a lot. Lack of self-control. Difficulty waiting turn. Calls out. Talks back. Loses temper. Inattention – – – – – Disorganized. Doesn’t pay attention/ listen. Makes careless mistakes. Doesn’t do schoolwork. Distractible. (Dendy 2000) The Not So Obvious Behaviours • However with ADHD there are a large number of problems that are not really visible and therefore not as obvious. Such problems include: • Impaired Sense of Time – – • Coexisting Conditions – – • Impairment in the following: working memory and recall, complex problem solving, internalizing language, alertness and effort. Two – Four Year Developmental Delay – • Having difficulty getting to sleep at night can result in students falling asleep in class or being irritable. Weak Executive Functioning – • Students with ADHD may have difficulty controlling their emotions and lose their temper easily. This can also mean they have a hard time seeing things from someone else’s perspective. Sleep Distrubance – • 2/3 children with ADHD will have at least one other condition which among others could include: Anxiety, depression, bipolar, tourette’s disorder, obsessive compulsive disorder, oppositional conduct disorder. Low Frustration tolerance – • Difficulty planning for the future. Impatient. Developmentally, students with ADHD can be between 2 – 4 years behind other students of the same age. This can be seen as having lower levels of maturity and responsibility than their peers. Not Learning Easily From Rewards and Punishment – This in particular can create challenges for teachers as students with ADHD may be much more difficult to discipline as they often are less likely to follow rules, they often do not learn from their past behaviours and are therefore likely to repeat misbehaviours. It can be very difficult for students with ADHD to change their behaviour. (Dendy, 2000) Things to keep in mind • Not all students with ADHD are alike. • They will not necessarily suffer from all of the above behaviours and problems but the ones that they face may be mild, moderate, or severe and can often vary from day to day (Barkley, 1997). • Students with ADHD may or may not be seeking out or using various treatments (whether behavioural or medical), but this up to the parents and students themselves to decide. However as a teacher, there are various recommended strategies that you can use in the classroom that will help with having a student with ADHD in your class. (Dendy, 2000) Classroom Strategies • There are quite a number of fairly simple strategies that can be applied in the classroom which have the potential to make a significant difference for students with ADHD. • Proximity help draw in attention so standing close to a student while you are teaching is a good idea. • As the lesson is progressing, walk around the room and tap the place in the student’s book that is currently being read or discussed to help bring the student back to the task. • Help the student to get started on the task e.g. come up with the first sentence of a story • Increasing the novelty of lessons by using films, tapes, flash cards or small group work can help to maintain a student’s interest in the work. • It is also a good idea to incorporate the students’ interests into lesson plans. • It is important to encourage the use of planning by frequently using lists, charts, pictures etc in the classroom. This can help to break things up into more manageable pieces for the students. (Healey, 2012) Classroom Strategies • Anticipate difficult situations and think about how to avoid/ manage them. – Transitions between lessons can be especially difficult. It is important to give advance warning of an upcoming transition and the expectation for it. • Let students know how long they are to work on a task or assignment and make sure there is a clock visible somewhere in the room. • Instructions should be clear and concise and it is a good idea to have the student repeat the instructions back before starting the task. This can be quite important as many students with ADHD have working memory problems. • Problem-solving should be modelled with each step explained. • Structure and routines are very important for students with ADHD so it is a good idea to have a written planned sequence of daily activities, but you need to keep these activities varied as well as consistent to stop them from becoming boring. • Don’t overload students with too much information at once. Vary the amount of work and be mindful of how much time they spend on task. (Healey, 2012) Classroom Strategies • Behavioural Priorities • There is often the case where students with ADHD always getting ‘told off’ more than other students. To help with this issue it is important to establish priorities over different behaviours. Many behaviours can actually just be ignored (e.g. humming) Other behaviours can actually be used as positive reinforcement after finishing a task (e.g. walking around). Creating opportunities for cooperative efforts with rewards for the whole group will encourage students to encourage each other. Focus more on using positive consequences for appropriate behaviours (e.g. being quiet, listening etc) than using negative consequences for problem behaviours. • • • • • Seating Strategies • When considering seating arrangements for the classroom you will need to think carefully about where you place a student with ADHD. They will benefit from being seated: – In a quiet area. – Near a good role model student. – Away from potentially distracting stimuli. • Workload • Students with ADHD will often require extra time to complete tasks and will struggle with tasks that require long periods of focused work. Shortening work periods and breaking tasks into smaller parts and making it so the end is in sight can really help make things more manageable for students with ADHD. (Healey, 2012) • Treatments • • • • • • • • Pharmacotherapy : (methylphenidate (Rubifen and Ritalin) or dexamphetamine (Dexedrine) 70 – 80% of children show improvement (such Pros: as reducing aggression and impulsive behaviour while improving attention span and compliance). Overall is considered more effective than Behavioural Treatment. Side effects can include appetite suppression (which can lead to nutritional deficiencies that could cause growth delays), sleep difficulties, nausea, and dehydration. If the child has underlying heart conditions, these can be aggravated. • Is easy to manage. (Ministry of Health, 2001) Cons: • • • • The long term use is less than 10% Good adherence to medication regimes tends to last less than 2 months Half of those who start using pharmacotherapy discontinue its use within a year. Can be difficult to consume for some children. (Healey, 2012) Behavioural Therapy: Pros: Children show improvement toward their symptoms of ADHD, but is not as efficient as pharmacotherapy (Ministry of Health, 2001). Parent stress has been shown to be reduced (Healey, 2012). In comparison to pharmacotherapy, it is much more expensive, and time consuming. Is much more labour intensive and those who are involved in the child's proximal environments also require training. • Cons: Is an alternative treatment (such as when parents do not wish to use pharmacotherapy, or when pharmacotherapy is ineffective) (Ministry of Health, 2001). • The treatment needs to be used continually in order to maintain improvements. (Ministry of Health, 2001) Current and Future Prospects Currently: Even when measures are taken for effective treatment, 32 – 64% of people still show noteworthy symptoms. Even after treatment, impairment remains for many, especially from a social context. There aren’t any long term benefits because the improvements cease once treatment stops. Future focus is exploring: Intervention involving neurocognitive areas of research within ADHD. Training involving attention as a primary focus. Training involving working memory as a primary focus. These areas are being explored because evidence has shown them to be effective. \ ENGAGE: (Enhancing Neurocognitive Growth with the Aid of Games and Exercise) • This is a new program currently in development. • 5 week program involving fun, hands-on activities and games • There are child and also parent sessions. • The games last for about 30 minutes in a day, first being taught to the parents. The parents then teach their kids the games. • Program covers: Executive skills, motor skills & exercise, affective skills, all while keeping it fun. Summary: (Of one study after a 5 week program) • Large reductions in hyperactivity scores from the children were found. • Children’s visuomotor and precision scores significantly increased. • The improvements shown continued for up to 12 months after the program had finished. • This program is still in the early stages of development but is showing promise. (Healey, 2012) References • • • • • • • • ADHD.org.nz. (2009). "The Diagnostic & Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders“. Retrieved from http://www.adhd.org.nz/DSM1.html American Psychiatric Association (1994). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental health disorders (4th ed). Washington DC: Author. Barkley, Russel A (1997) ADHD and the Nature of Self-Control. New York: The Guildford Press, 1997 Dendy, Chris A. Zeigler (2000) Teaching Teens with ADD and ADHD – A Quick Reference Guide for Teachers and Parents. Bethesda, Maryland, Woodbine House Inc. 2000 Frey, R. (2012). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Retrieved from http://www.minddisorders.com/Del-Fi/Diagnostic-and-Statistical-Manual-of-MentalDisorders.html Green M, Wong M, Atkins D et al. 1999. Diagnosis of Attention-Deficit/ Hyperactivity Disorder. Technical Review no. 3. (Prepared by Technical Resources International, Inc under contract no. 290–94–2024.) AHCPR Publication no. 99–0050. Rockville, MD: Agency for Health Care Policy and Research. Healey, D (2012) ADHD: Where Are We Going?[PowerPoint slides], Unpublished manuscript, University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand Ministry of Health. (2001). New Zealand Guidelines for the Assessment and Treatment of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Wellington, N.Z.: Author.