File - English Language

advertisement

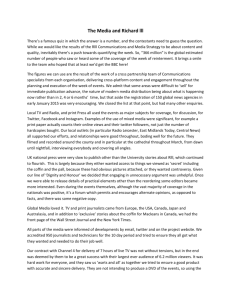

AS English Language Exam Questions and Wider Reading for Paper 2, Section A 1 Throughout this unit of work, you will use this booklet to access: wider reading additional resources exam questions mark schemes model answers. Contents Page 3/4 – ‘Twitter Is Not the Enemy of the English Language’ Page 5/6 – ‘Twitter users forming tribes…’ Page 7 – Tribes Data Page 8/9 – ‘How Social Media is Changing Language’ Page 10/11 –‘Teacher told to sound less Northern’ Page 12 – ‘Midlands school BANS children from using ‘damaging' Black Country dialect’ Page 13/20 – ‘Academic Degree Level Essay – Has the English language achieved global significance?’ Page 21 – ‘Jafaican may be cool, but it sounds ridiculous’ Page 22 – ‘Language Case Study – Shahnaz’ Page 23 – ‘Etiquette for Women’ Page 24 – ‘Exam Style Questions on Diversity and Change’ Page 25 – ‘Assessment Objectives’ ‘AS Component Two Sample Question’ Page 26 – ‘Sample Exam Question’ Page 27 - ‘AS Component Two Mark Scheme’ Page 28/29 – ‘AS Component Two Model Response’ 2 Twitter Is Not the Enemy of the English Language REBECCA GREENFIELD Contrary to all the LOLs, emoticons and hashtags happening in feeds across the Twittersphere, Twitter isn't destroying the English language, it's making it better. The medium only allows for 140 character musings, lending itself to abbreviations that don't exactly follow conventional spelling or grammar rules. Linguist Noam Chomsky finds the whole thing appalling, calling it "very shallow communication" in an interview with DC blog Brightest Young Things. "It requires a very brief, concise form of thought and so on that tends toward superficiality and draws people away from real serious communication … It is not a medium of a serious interchange," he told Jeff Jetton. But while a few language snobs are in Chomsky's camp, the rest of the linguistic community doesn't exactly agree. Twitter is all about slang and abbreviations, but it's just not eroding the English language. In fact, University of Pennsylvania linguistics professor Mark Liberman found the exact opposite: It's making it better. Some assume that Twitter using kids on the Interwebs are getting used to speaking in short bursts filled with non-sensical slang terms and therefore cannot communicate like the sophisticates of the olden days. "Our expressiveness and our ease with some words is being diluted so that the sentence with more than one clause is a problem for us, and the word of more than two syllables is a problem for us," explained actor Ralph Fiennes, noted The Telegraph. Liberman decided to look into this so called word shortening phenomenon that's happening and it turns out to be completely false. Liberman compared recent tweets from Penn newspaper The Daily Pennsylvanian's Twitter feed to text from Hamlet. "The mean word length in Hamlet (in modern spelling) was 3.99 characters; in P. G. Wodehouse’s Jeeves stories, the mean word length was 4.05 characters; in the DP‘s tweets, the mean word length was 4.80 characters," he found, writing on linguistic blog Language Log. And even if the type of communication doesn't live up to Chomsky's lofty English ideals, it might not matter much. It's a 21st century language tool and other linguists aren't about to ignore it. Feeds have become a research hub for others looking to study language and mood, as The New York Times's Ben Zimmer points out. "Social scientists can simply take advantage of Twitter’s stream to eavesdrop on a virtually limitless array of language in action," he writes. 3 And they have. Linguists have looked at phenomenons like Twitter moods and Arab revolutions. Beyond mood and revolutions though, linguists have started to study the actual changes to the English language via Twitter. Zimmer points to a study by Carnegie Mellon researches that mapped regional language use across the country. "Like the profusion of hella as a form of emphasis in Northern California, as in, 'It’s hella cold out there,'" explains Zimmer. The study garnered criticism, but this is the type of research linguists do and Twitter just makes it that much easier, continues Zimmer. "The amount of data available for analysis is many orders of magnitude bigger than what could be collected with traditional dialect surveys," he writes. Whether Chomsky approves or not, Twitter's happening and it's really not all that bad. Language evolves, Twitter's just making it easier to track what's happening. 4 Twitter users forming tribes with own language, tweet analysis shows Analysis of millions of tweets finds more precise use of social media which seems to contradict idea that Twitter users want to share everything with everyone. Twitter users are forming 'tribes', each with their own language, according to a scientific analysis of millions of tweets. The research on Twitter word usage throws up a pattern of behaviour that seems to contradict the commonly held belief that users simply want to share everything with everyone. In fact, the findings point to a more precise use of social media where users frequently include keywords in their tweets so that they engage more effectively with other members of their community or tribe. Just like our ancestors we try to join communities based on our political interests, ethnicity, work and hobbies. The largest group found in the analysis was made up of African Americans using the words 'Nigga', 'poppin' and 'chillin'. That community was one of the more close-knit, 5 sending around 90% of messages within the group. Members also tended to shorten the ends of their words, replacing 'ing' with 'in' or 'er' with 'a'. (See the on page 7 for a fuller tribal breakdown) Prof Vincent Jansen from the School of Biological Sciences at Royal Holloway, the institution which published the Word Usage Mirrors Community Structure in the Online Social Network Twitter report with Princeton University, explained: Interestingly, just as people have varying regional accents, we also found that communities would misspell words in different ways. The Justin Bieber fans have a habit of ending words in 'ee', as in 'pleasee'. To group these users into communities, the researchers turned to algorithms from physics and network science. The algorithms worked by looking at publicly sent messages between users. In the graphic above, the top word given for each tribe is the most significant one in that community. Circles represent communities, with the area of the circle proportional to the number of users. The widths of the lines between circles represent the numbers of messages between or within community. The colours of the loops represent the proportion of messages that are within users from that group - from yellow 0% to red 100% . Dr John Bryden, also at Royal Holloway, said that his team can now work out which tribes we belong to by analysing our tweets. Given enough data, Bryden said that this can be done "with up to 80% accuracy". The research team hopes the data gathered from the project, which has been running since 2009, could offer a more accurate insight into the changing language used by different communities on Twitter. By learning these languages researchers hope new ways will emerge of engaging with Twitter tribes – rather simply using conventional Twitter features such as hashtags. 6 Tribes Data Twitter tribe Nigga - used liberally by African Americans Sxsw - people attending the sxsw conference Graditude - social movement Rubbish - people from the UK Tbr - fans of comics and novels Pelosi - right-wing American community Tdd - software developers Foodies - users who share recipes Bieber - fans of Justin Bieber Avn- Twitter users sharing and discussing pornography Melb - Australian users Playoff - sports fans Pastors - Christian Twitter users Bhi - Indians who use a mix of english and hindi Pln- teachers often discussing online technology Anipals - animal welfare Blogtv - TV and youtube fans who blog Singtel - Twitter users from Singapore Kstew - fans of the twilight vampire movies Kradam - Adam Lambert was an American Idol Ddub - fans of the New Kids on the Block Jhb - South Africans Alterra - University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee community Number of tribe Tweets members sent How many more times words used in a community compared to that of regular twitter user 25953 33540192 nigga = 6.57; yall = 5.7 21799 16361985 sxsw = 3.8; presentation = 2.44 21181 20581951 gratitude = 4.28; teleseminar = 6.79 11001 9560134 rubbish = 8.84; bloke = 9.34 7235 6066777 tbr = 20; sdcc = 15.2 6858 4836 6631668 pelosi = 17.2; dems = 13.1 3895191 tdd = 21.3; devs = 10.4 4522 3928 3323157 foodbuzz = 29.5; braised = 14.4 5062956 bieber = 26.8; selena = 21.5 3390 2770 2765 2794983 avn = 24.5; brazzers = 40.5 2421979 melb = 42.3; telstra = 48.1 2141153 playoff = 11.2; offseason = 23.2 2256 1694308 pastors = 27.6; missional = 55.1 1487 1438492 bhi =106; nahi = 105 1354 1152 1115497 pln = 76.2; voicethread = 119 1441651 pawsome = 123; furever = 140 875 784286 blogtv = 46.4; sitnb = 199 875 757457 singtel = 142; starhub = 154 749 996690 kstew = 141; robsten = 143 566 677024 kradam = 283; glamberts = 264 545 513 278 1124209 ddub = 275; twug = 203 419075 jhb = 275; jozi = 266 264717 alterra = 357; uwm = 342 7 How social media is changing language From unfriend to selfie, social media is clearly having an impact on language. As someone who writes about social media I’m aware of not only how fast these online platforms change, but also of how they influence the language in which I write. The words that surround us every day influence the words we use. Since so much of the written language we see is now on the screens of our computers, tablets, and smartphones, language now evolves partly through our interaction with technology. And because the language we use to communicate with each other tends to be more malleable than formal writing, the combination of informal, personal communication and the mass audience afforded by social media is a recipe for rapid change. From the introduction of new words to new meanings for old words to changes in the way we communicate, social media is making its presence felt. New ways of communicating An alphabet soup of acronyms, abbreviations, and neologisms has grown up around technologically mediated communication to help us be understood. I’m old enough to have learned the acronyms we now think of as textspeak on the online forums and ‘internet relay chat’ (IRC) that pre-dated text messaging. On IRC, acronyms help speed up a real-time typed conversation. On mobile phones they minimize the inconvenience of typing with tiny keys. And on Twitter they help you make the most of your 140 characters. Emoticons such as ;-) and acronyms such as LOL (‘laughing out loud’ – which has just celebrated its 25th birthday) add useful elements of non-verbal communication – or annoy people with their overuse. This extends to playful asterisk-enclosed stage directions describing supposed physical actions or facial expressions (though use with caution: it turns out that *innocent face* is no defence in court). An important element of Twitter syntax is the hashtag – a clickable keyword used to categorize tweets. Hashtags have also spread to other social media platforms – and they’ve even reached everyday speech, but hopefully spoofs such as Jimmy Fallon and Justin Timberlake’s sketch on The Tonight Show will dissuade us from using them too frequently. But you will find hashtags all over popular culture, from greetings cards and t-shirts to the dialogue of sitcom characters. Syntax aside, social media has also prompted a more subtle revolution in the way we communicate. We share more personal information, but also communicate with larger audiences. Our communication styles consequently become more informal 8 and more open, and this seeps into other areas of life and culture. When writing on social media, we are also more succinct, get to the point quicker, operate within the creative constraints of 140 characters on Twitter, or aspire to brevity with blogs. New words and meanings Facebook has also done more than most platforms to offer up new meanings for common words such as friend, like, status, wall, page, and profile. Other new meanings which crop up on social media channels also reflect the dark side of social media: a troll is no longer just a character from Norse folklore, but someone who makes offensive or provocativecomments online; a sock puppet is no longer solely a puppet made from an old sock, but a self-serving fake online persona; and astroturfing is no longer simply laying a plastic lawn but also a fake online grass-roots movement. Social media is making it easier than ever to contribute to the evolution of language. You no longer have to be published through traditional avenues to bring word trends to the attention of the masses. While journalists have long provided the earliest known uses of topical terms – everything from 1794’s pew-rent in The Times to beatboxing in The Guardian (1987) – the net has been widened by the ‘net’. A case in point is Oxford Dictionaries 2013 Word of the Year, selfie: the earliest use of the word has been traced to an Australian internet forum. With forums, Twitter, Facebook, and other social media channels offering instant interaction with wide audiences, it’s never been easier to help a word gain traction from your armchair. Keeping current Some people may feel left behind by all this. If you’re a lawyer grappling with the new geek speak, you may need to use up court time to have terms such asRickrolling explained to you. And yes, some of us despair at how use of this informal medium can lead to an equally casual attitude to grammar. But the truth is that social media is great for word nerds. It provides a rich playground for experimenting with, developing, and subverting language. It can also be a great way keep up with these changes. Pay attention to discussions in your social networks and you can spot emerging new words, new uses of words – and maybe even coin one yourself. 9 Teacher ‘told to sound less northern’ after southern Ofsted inspection A teacher has been told to tone down her northern accent as a result of criticism by school inspectors. The teacher, who is working in west Berkshire but hails from Cumbria, has been set this by her school as one of her "targets" to improve performance, her union said today. "You could write it off as humorous at first sight - but the more you think about it the more it should make your blood boil and should stagger you," said Paul Watkins, executive member of the National Association of Schoolmasters Union of Women Teachers for west Berkshire, said. "If you'd said it about a Welsh accent or ethnic minority group, you would be accused of being racist." He added: "Apparently, the beginning of this was Ofsted (the education standards watchdog), who made a comment about her accent. As a consequence of that comment, it was decided that would be a reasonable objective to impose upon the member. She was told she needed to make her northern Cumbrian accent sound more southern. "How do you assess whether her accent is more or less southern. It's the most ridiculous thing I've ever heard of." "I think she has taken the approach of it being unbelievable," said Mr Watkins. "I think that she - and credit to her - has seen the good humour in this in that she thinks it's so farcical and bizarre. You couldn't make it up." Mr Watkins, who declined to name the school on the grounds it would put an embarrassing spotlight on the teacher, said there were "a number of on-going issues at the school" - including its potential transformation into an academy. Not surprisingly, the incident has gone down like a lead balloon in Cumbria with Eric Robson, the chairman of the Cumbrian Society, saying: "That school should be put in special measures immediately. It's ridiculous." Louise Green, editor of the Lakeland Dialect Society, added that the Cumbrian accent was "the most wonderful thing" about the county. "To try and remove it is like trying to remove Beefeaters," she said. "We should be celebrating our different regional ways of speech and promoting and protecting them." 10 A spokesman for Ofsted said it would be happy to investigate the matter if it was given the name of the school. "Inspectors comment on the standard of teaching at schools," he added. "Negative comments about the suitability of regional accents are clearly inappropriate and should form no part of our assessment of a school's or a teacher's performance." The incident comes just a week after a school in the Black Country - Colley Lane, primary, Halesowen - gave its pupils a list of ten banned regional phrases which, it said, could damage their prospects. These included "ya cor" meaning "you can't" and "ay?" instead of "pardon". Headteacher John White said: "It is about getting them ready for job interviews." 11 Midlands school BANS children from using 'damaging' Black Country dialect Staff at the West Midlands primary have drawn up list offending phrases They include 'I cor do that' instead of 'I can't do that' and 'Ay?' Parents and local residents have branded the move as 'snobbish' But the school says it wants it children to have 'the best start possible' Children at a primary school in the West Midlands have been told to speak proper English instead of the Black Country dialect to halt a ‘decline in standards’. Those who say they ‘cor do that’ – ‘can’t do that’ – will not be punished, but they will be corrected every time they utter an outlawed phrase. Angry parents criticised the ban at Colley Lane Primary School in Halesowen, claiming it is ‘snobbish’ and ‘insulting’. A letter posted to parents last week said the school wanted pupils to have the ‘best start possible’. It added: ‘Recently we asked each class teacher to write a list of the top ten most damaging phrases used by children in the classroom. We are introducing a “zero tolerance” in the classroom to get children out of the habit of using the phrases on the list.’ The Black Country includes Dudley, Sandwell, Walsall, and southern parts of Wolverhampton. Other words and phrases on the prohibited list include ‘ay’, meaning ‘pardon’, and ‘I day’, meaning ‘I didn’t’. Alana Willetts, 30, whose nine-year-old son George goes to the school, said staff should be teaching pupils about the Black Country and its dialect. ‘Some of my friends have gone on to be doctors and lawyers and I’m an engineer – [the accent] doesn’t affect you as a person,’ she said. ‘I think it is patronising and insulting to say that people with a Black Country accent are disadvantaged. All the parents are outraged.’ Ann Mills, 62, who has two grandchildren at the school, added: ‘I was raised here and I’m proud of the way we speak.’ 'If they can't say it, it is likely they can't read it, and even less likely they can write it. 'We value the dialect but we want to encourage children to learn when to use and when not, like for a job interview. It is, of course, fine to use in other situations and we would celebrate that. 'We know it is a topic lots of people will be interested in, but I'm positive about it. If it starts to get people talking about the issue, that can only be a good thing. 'We will correct children if they get the words wrong.' The school was rated as either Good or Outstanding in a Ofsted inspection report in 2010. 12 Academic Degree Level Essay – Has the English language achieved global significance? The extent to which the English Language has achieved global significance is phenomenal, in that no other language has ever been able to achieve such a status of linguistic eminence. According to Crystal (1997) a language achieves global status when it develops a special role that is recognised, either culturally or politically, in every country, across every continent of the world. He also signifies that a global language is not affected by the quantity of those who speak the language, but much more concerning who those people are, in that ‘without a strong power base, whether political, military or economic, no language can make progress as an international medium of communication.’ (Crystal, D. 1997:5) Throughout history, an international language becomes so for one principal reason; that being ‘the political power of its people.’ (Crystal, D. 1997:7) It is important to look at the historical significance of English in its ascension to linguistic dominance and its current position as an international language. There are two primary facets in relation to this ascension, them being geographical-historical and socio-cultural aspects. The geographical-historical aspect determines how English reached its position of pre-eminence, whilst the socio-cultural aspect provides an explanation as to why the language remains in this position of power. Speakers of English throughout the world have come to be dependant on the language as a tool, in respect to politics, economy, communication, entertainment, the media and of course, education. (Crystal, D. 1997) The language therefore becomes a convenience for speakers, in which international domains can be accessed through the aforementioned lingua franca. Crystal (1997:25) states that the justification of having a lingua franca, that is; a common language, is that the language is able to ‘serve global human relations and needs.’ The fact that English is now represented in countries on every continent around the world, as either an official language or by having prestige within a county’s foreign language teaching system, provides reason for applying the term ‘global’ to the English language beyond doubt. The spread of English beyond Europe and the British Isles is accredited to four centuries of colonialism and British imperialism, which led to English being spoken by over three hundred million people. (Leith, D. 1997) The first significant stride in the advancement of English towards its pre-eminence as a world language occurred during the early trade in the Atlantic. Leith (1997:182) articulates that by the year 1600, England had gained trading contacts across three continents, which retrospectively provided a powerful platform on which the English language was to flourish and become the globally dominant medium of communication that it is at present. Trading companies such as the Newfoundland fur trade, the ivory and gold trade on the western coast of Africa and the East India Company brought speakers of English into economic contact throughout the world. (Leith, D. 1997:182) 13 English and the English-based pidgins created in parts of West Africa, acted as lingua francas of common communication during the colonial period. These pidgins during the slave trade were the only means of communicating with other Africans. Eventually, pidgins became the first languages of African slaves’ children and grandchildren. ‘To operate as first languages, the functions of pidgins had to be elaborated, their structures amplified: they became creoles.’ (Leith, D. 1997:184) This evolution and expansion of the English language plays a significant role in its cultural history, in that the archetypal English culture was becoming diversified; allowing other cultures the opportunity, if not consciously, to submerge their societal mores into the core of the language. Regarding the spread of the English language in relation to colonialism, the need for settlement in specific areas was analogous to the altering political, social and economic revolutionary. ‘English has become a world language because of its wide diffusion outside the British Isles, to all continents of the world, by trade, colonisation, and conquest.’ (Barber, C. 1993:234) The first permanent English colonisation settlement overseas dates from 1607, when colonists arrived in what was to be named Jamestown and Virginia, after James I and the ‘virgin Queen’ Elizabeth. (Crystal, D. 1997:26) In November 1620, the first group of Puritans, thirty-five members of the English Separatist Church, and sixty-seven other settlers arrived at Cape Cod Bay, and established settlement in what came to be named Plymouth, Massachusetts. The settlers were particularly diverse and dissimilar in age, with young infants to those in their fifties, with varied regional, social and work-related backgrounds. This diversity would have undoubtedly created a range of social attitudes and societal beliefs, as well as an array of regional accents and dialects within the settlement. With regards to the Puritan colonists, their movement occupied and encompassed both social and political constituents, which would therefore have had ecclesiastical influence on the English Language within the settlement. In looking back to the origins of Puritanism in the seventeenth century, the movement was a great contributor to the development of the English language. They showed preference to English rather than Latin and professed that English was a national language capable bringing together all English speakers. This is certainly the case in contemporary society, as English has become the global language, in effect: the lingua franca of communication that brings English speakers together. Furthermore, the language still maintains its association with religion and Catholicism to this day, which marks a cultural dynamic that has thus resisted change. English settlements continued in North America throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, with settlements in the West Indies drawing competition from the Spanish, French and Dutch colonisers. Yet by the early nineteenth century, Britain had power over many of the Caribbean islands, including Trinidad, Jamaica and Barbados. (Barber, C. 1993:235) Britain’s ascendancy as a governing political power continued to expand, with colonies in the Indian subcontinent dating from the latter half of the eighteenth century, and also settlement in Australia after the American War of Independence (1775-1783). The American Revolution not only formed a new nation; it also divided the English Language into ‘two streams,’ producing deviation in the spelling or the lexical construction of words with the same semantic loading, for 14 example, ‘theatre’ versus ‘theater.’ (Mencken, H, L. 1936) This deviation suggests that although America embraced the English Language, the need to be viewed as self-governing and independent is evident through language variation. It is credible that the English language established what was, during this period of significant cultural diversification and politic plight, ‘a medium which gave them access to common opportunity.’ (Crystal, D. 1997:31) Between the first American census in 1788 and 1950, the population had grown from 4 million to 150 million. According to Barber (1993), it is surely American political and economic power that accounts for the dominant position of English in the world today, in that America has ensured its global policy on English as a world language through both cultural and political history. America’s economic presence and military might during the twentieth century have both established and maintained the English language’s global prominence: the media, progress in science and industry and Hollywood, have all been contributors to its ascension. Hollywood has had an effect on the world and its thought processes, both politically and culturally, and simultaneously; both negatively and positively, due to substantial worldwide exposure which has undoubtedly had a significant effect on the spread of English. Negatively, Hollywood appears to promote a biased and markedly Americanised vision of the world as a whole, depicting an over-simplified view of international divergences, in which ‘stereotyped and negative images of Muslims, Russians, South Americans (…) are presented as the enemies of freedom and progress. (Web 4) With reference to history, it is suggested that Hollywood misrepresents authentic historical events, in ‘downplaying the contribution of other nations to allied victory,’ through mediums such as film and television. (Web 4) This representation further asserts American dominance and supremacy in relation to political and cultural means, which could account for the emergence of English as a global language. However, on the contradictory, Hollywood can also be viewed as far from ‘monolithically American,’ (Web 4) in that directors from diverse non-English language film cultures have introduced new cultural perspectives to Hollywood through both film and television effectively and successfully. This demonstrates that Hollywood is both accommodating of other cultures, as well as the transmission of those cultures through an English speaking medium, which would therefore create heightened exposure of the English language globally. Economically, Hollywood’s financial power and worldwide publicity allows domination and supremacy in globalised entertainment, whilst ensuring ‘cultural exports are classed as just another form of trade in international agreements, and to help it gain control over distribution networks abroad.’ (Web 4) This ‘control’ indisputably has an effect on English as a world language, as it in inevitable that non-speakers of English would want to gain knowledge of the language to thus enable themselves with the opportunity to experience the global phenomena that is Hollywood. In retrospect to the expansion of British influence and political power with regards to colonisation, it ‘continued at an even greater rate during the nineteenth century.’ (Barber, C. 1993:235) Early in the century, British rule countermanded the Dutch in South Africa, and also established colonies in Singapore, New Zealand and Hong Kong. The latter half of the nineteenth century saw the world’s colonial powers competing for the African continent, a dispute which saw colonies established by Britain in western, eastern 15 and southern Africa. English has been extremely influential in the aforementioned areas, producing many varieties of the language that is used for diverse purposes and in differing social contexts. Barber (1993) states that in colonies such as those in North America, Australia and New Zealand, settlers who had English as a native tongue outnumbered the original populace, and furthermore dominated them both economically and politically. The native languages therefore had infinitesimal influence on the settlers’ language, which allowed English to develop and expand in these colonies. As a contrast, in South Africa, the majority of the population speak a ‘Bantu language such as Zulu or Xhosa.’ (Barber, C. 1993:236) Speakers of Bantu languages outnumber English speakers on a ratio of one to three. (Barber, C. 1993:236) Notwithstanding this ratio, South African English has surprisingly resisted influence from Bantu languages and other languages of the country, and Barber assumes that the ‘long period of British domination and the consequent cultural prestige of English,’ (Barber, C. 1993: 237) are responsible for the opposition to change or influence. This demonstrates that even in areas where speakers of English were the minority, the language has the authoritative power to implement its position in society through both cultural and political history. English as a second language (wherein it is used together with other local languages for communicative purposes between different language-groups within the community) has become prominent in many previously colonised areas, such as Singapore. During the colonisation of Singapore under British rule, the country’s population expanded considerably. Many ethnic groups from other colonies such as India and Ceylon settled in Singapore, as well as settlers from bordering areas, the largest group of migrants being from Southern China. (Web 1) According to the Singapore Census of the year 2000 of ‘resident population and ethnic group,’ the Singaporean population now consists of approximately 77% Chinese, 14% Malay, and 8% Indian, which consequently shows great diversity in ethnic origin; this diversity creating the need for bilingualism. (Web 2) Bilingualism in Singapore shows the extent to which the English language has developed into a world language through cultural and political factors both historically and contemporary. English in Singapore is associated with economic and societal prestige; a lingua franca used as a common medium of communication in administrative and economic spheres. The languages spoken in Singapore are used in different social contexts, wherein, English is used in the educational and academic system as well as at home in familial setting. ‘At one time, Chinese was the principle medium of education, but, despite independence (1965), English-medium education has spread until it is now almost universal (…)’ (Barber, C. 1993:239) So as to not deny the speakers native cultural heritage, Mandarin, Malay and Tamil are also taught in schools, and are used alongside English at home. Furthermore, Cantonese would be used to communicate with the older generation if they are monolingual in the aforesaid language. Speakers of Singaporean English are conscious of the functions of the language as a lingua franca in relation to economical and political facets; they observe English as a unifying factor that connects the community via socio-economical and political dynamics. 16 In Hong Kong, English is used alongside Cantonese; them both obtaining official language status. However, their purposes in terms of socio-constructive aspects differ accordingly. English is the language used in the legal system, education, commerce and industry and the media, yet common daily communication within society is spoken in Cantonese; the use of English for this purpose being found objectionable. Therefore, English is observed as a ‘language of power’ whilst Cantonese is the ‘language of solidarity and an expression of ethnicity.’ (Barber, C. 1993:239) Moreover, the Chinese community are aware of the influence that the English language bears in terms of political and economic authority around the globe. Yet, unlike Singaporean speakers of English; they decline to use the language in familial setting, so as to maintain their own identity and cultural legacy, differentiating the official languages in terms of formal and interpersonal purpose. Crystal (1997) states that Cantonese is the mother tongue of over 98% of the population, however estimates in 1992 suggested that over 25% of the population now have some competence in the English language. He also articulates that ‘there is incredible uncertainty surrounding the future role of English, after the 1997 transfer of power,’ ending 156 years under British control. (Crystal, D. 1997:51) Conversely, he further states in his 2003 second edition, that ‘patterns of use so far have shown little change,’ which furthermore demonstrates the standing power of English as a global medium of communication. (Crystal, D. 2003:59) Crystal (1997), states that there is vast distinction in the motives for selecting a particular language as a preferred foreign language in any given country. These reasons incorporate historical conventions, political expediency, and the aspiration for commercial, cultural or technological contact. Early in the twentieth century, economic developments were operating on a global scale, ‘fostering the emergence of massive multinational organisations.’ (Crystal, D. 1997:8) As British political imperialism during the nineteenth century had allowed the English language to disperse globally, the growth and expansion of competitive industry and business, equalling international marketing and advertisement in the twentieth century, further elevated English into a position of secure governance. The development and expansion of English language as a global language has however caused controversy and an amalgamation of predicaments regarding whether ‘English should be retained as an official language,’ and whether the standard form of English or the local variety should be adopted in teaching. (Barber, C. 1993:241) A variety of factors have contributed to this reaction; them being ‘nationalist feeling, attachment to traditional culture, desire for advances in science and technology, and the conflicting needs for local and for international communication.’ (Barber, C. 1993:242) As an exemplar, Barber (1993) affirms that after India gained Independence in 1947; the inhabitants of the Northern regions of India were in favour of using Hindi as the official language of the country, whilst the Dravidian speaking Southern population favoured the preservation of English. Southerners were aware that ‘Hindi as the main language would give obvious economic and political advantages’ (Barber, C. 1993:242) to those in the North and sought to resist Hindi’s advancement as an official language for this reason. 17 In referring back to British colonisation, the impact of the East India Company in the early 1600’s, eventually produced a distinct variation of English: Indian English. In India, ‘English now has national and international functions that are both distinct and complementary. English has thus acquired a new power base and a new elitism.’(Kachru, B. 1986:12) Baldridge (2002) states that only 3% of India’s population speak English; those being the ‘individuals who lead India’s economic, industrial, professional, political, and societal life. ‘(Web 3) Within India, English serves as the language of the aforesaid domains of society, in which it carries an unyielding degree of prestige and stature, offering many linguistic advantages to those who speak the language. Linguist Braj Kachru has suggested that we view the spread of English to global dominance as ‘three concentric circles.’ (Crystal, D. 1997:53) These circles show the way in which English has been acquired and the way in which it is being used in currently. The inner circle, applies to the countries in which English is the primary language, such as the UK, USA, Canada, Ireland, Australia and New Zealand. The outer section encompasses the earlier stages of the expansion of English in non-native locations, wherein English has become an official language or has assumed a position of importance in second language acquisition in countries such as Singapore and India. The expanding circle ‘involves those nations which recognise the importance of English as an international language, though they do not have a history of colonisation by members of the inner circle, not have they given English any special administrative status.’ (Crystal, D. 1997:54) The expanding circle includes Japan, China, Greece, Poland and a progressively rising number of other countries in which English is taught as a foreign language. The significance of the concentric circles is that they illustrate the divisions of how English has come to be a world language, through both historical aspects of colonisation and the political and cultural facets of the economic revolution. Kachru (1986), states that assumptions regarding language and power arise from historical, political and economic facets; in that the power of a language is ultimately connected with societal control and supremacy. It is certainly exploitation and colonisation that has acted a vehicle in the principal expansion and spread of English, alongside cultural and political aspects that sustained its presence as a globally dominant medium of communication. As it stands, English is accountable for bringing together every continent of the world through the ideal of a lingua franca, governed by political factors. However, there are dangers that a global language can stimulate, consequently including the proposal of a monolingual class; indifferent in their approaches to other languages, the manipulation of a language at the expense of those who have no knowledge of it, and lastly, a global language could accelerate the eradication of minority languages by means of making them unnecessary. (Crystal, S. 1997:12) The English language has however, firmly secured its label as a ‘global’ language in contemporary society and in the foreseeable future. 18 REFERENCES Barber, C. (1993) The English Language: A Historical Introduction. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge. Crystal, D. (1997) English as a Global Language. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge. Crystal, D. (2003) English as a Global Language (2nd ed) Cambridge University Press: Cambridge. Kachru, B (1986) The Alchemy of English: The spread, functions, and models of nonNative Englishes. Pergamon Press Inc: New York Kachru, B. (1986c) ‘The Power and Politics of English.’ World Englishes, Vol. 5: No. 2-3: 121-140. Leith, D. (1997) A Social History of English (2nd ed) Routledge: London. Mencken, H, L. (1936) The American Language: An inquiry into the development of English in the United States. AA Knopf: University of Michigan. WEBLIOGRAPHY Web 1: http://www.une.edu.au/langnet/definitions/singlish.html#bkgd-SCE Title: Singapore Colloquial English (Singlish) Author: Jeff Siegel (University of New England) Last Modified: Not Known Date Assessed: 10/11/08 Web 2: http://www.singstat.gov.sg/stats/themes/people/indicators.pdf Title: Key Indicators of the Resident Population (2000 Census) Author: Singapore Government 19 Last Modified: 30th June 2007 Date Accessed: 10/11/08 Web 3: http://www.languageinindia.com/junjul2002/baldridgeindianenglish.html Title: Linguistic and Social Characteristics of Indian English (Language in India) Author: Jason Baldridge (M. S. Thirumalai, Ph.D. & B. Mallikarjun, Ph.D. eds) Last Modified: July 2002 Date Accessed: 11/11/08 Web 4: http://www.idebate.org/debatabase/topic_details.php?topicID=57 Title: Hollywood’s Influence: Does Hollywood have a negative impact on the world? Author: Alastair Endersby (UK) Last Modified: 01/11/00 Date Accessed: 11/11/08 20 I was surprised a few years ago to hear an acquaintance more Left-wing than me (admittedly that’s not saying much) saying he was moving out of London because he’d just had kids and “didn’t want them growing up talking like Ali G”. And Paul Weller said the same thing in an interview with the Telegraph a few years later, about his choice of school for his kids, although perhaps having mixed-race children made him feel bolder about facing any accusation of racism. And I don’t think an aversion to Jafaican (fake Jamaican), which according to the Sunday Times (£, obviously) will have completely replaced Cockney by 2030, is racial. The West Indian accent from which it came is fairly pleasant, nice enough for various drink makers to use it to flog us their products. However, its by-product is rather unpleasant, sinister, idiotic and absurd. Imagine that an Englishman were to start speaking in an inexplicable French or German accent – people would probably take the trouble to wind down their car windows to shout abuse at him. Yet enough people talk with an affected West Indian accent for it to become an accent, Jafaican, partly thanks to Radio One’s Tim Westwood, and despite the Sacha Baron-Cohen character, Ali G, mocking the phenomenon. It’s unusual for a small minority to actually change a city’s accent, in this case one that is supposed to date back to the time of Chaucer (although how similar a cokenay of that time would have sounded to modern-day cockneys is hard to know). The only previous British accent to have been significantly changed by immigration is Scouse, which took on a distinctive Irish sound in the late 19th-century, but the Irish made up well over of a third of the city. West Indians are barely 10 per cent of the London population. Multiculturalism probably played a part. Jafaican’s rise may have been accelerated by the 1975 Bullock Report into education, "A Language for Life", which heralded the start of multiculturalism in the classroom. It recommended that “No child should be expected to cast off the language and culture of the home as he crosses the school threshold, and the curriculum should reflect those aspects of his life”, and recommended that teachers were expected to have an understanding of Creole dialect “and a positive and sympathetic attitude towards it”. Never mind that speaking Creole would not have been much of an advantage for a young black kid trying to get on in London; there seems to have been a general approach in teaching that accents were authentic and should not be ironed out. And the replacement of Cockney with Jafaican may reflect something more profound. Accents and fashions display underlying insecurities and cultural aspirations; the rise of Received Pronunciation reflected a desire by the lowermiddle class and provincials to embrace the values, lifestyles and habits of the British upper-middle class. In London the adoption of Jafaican, even among the privately educated, reflects both a lack of confidence in British cultural values and an aspiration towards some form of ghetto authenticity. Anyway, what are house prices in North Yorkshire like at the moment? 21 Language Case Study – Shahnaz Shahnaz is a black British woman in her early twenties. She was born and raised in South London, went to a state secondary school and then sixth form college, before studying for a BA at the University of Manchester. Here, she talks about some of the factors that affect her language use: Both of my parents were born in the UK, therefore I am second-generation Jamaican diaspora. I, personally, don't have a lot of contact with my family in Jamaica and I have never been there. My parents to not speak Patois unless they are with their Jamaican friends and family and it is usually used in a colloquial manner, usually in jest. My nan speaks with a Patois accent. However, her lexicon is English-based – when my nan was in Jamaica, her family was considered lower middle class, and more ‘British’ sounding words were encouraged. In formal situations I use Standard English; sometimes, I may even use a more Standard version of English, especially if I was speaking to upper-class people at University who I did not know. However, if I am familiar with someone (even if they are upper class) I will slip back into my vernacular, which I would class as ‘slight BBE’ (Black British English). When I was in Manchester, a lot of people said that I had a strong South London accent. I lived in a house with Londoners in my final year of University and was told that my accent was the strongest (relating to BBE). I think I spoke with a more Standard English variety in Manchester because I was reading a lot of articles and books, and we would often have debates relating to scholarly material. However, at home, we used to mimic African accents in jest, which ultimately became part of our vernacular. We would use words such as ‘chale’ (Ghanaian Twi word for ‘friend’) ‘sha’ (a West African expression similar to ‘hun’ or ‘honey’) and ‘kai’ (usually an expression of shock). We also used common Nigerian Pidgin English phrases like ‘you no de tell lies’ (‘you’re not lying’). With my Somalian friend, she was also Muslim, so at times we would use words like ‘walahi’ (similar to ‘swear down’ or ‘I swear it’s true’). I only usually speak Patois when I am imitating my nan or a person I know that has a strong Patois accent, or if I am using humour or reciting lyrics from Jamaican music. I only really have one close Jamaican friend as my close friends come from other backgrounds (Asian, other Caribbean Islands, Nigeria, Somalia, Syria, etc.) so at times, I may use a form of Nigerian Pidgin English with them, or variations of their languages and words I have picked up. 22 23 Exam Style Questions (Your teacher will also give you a small data set to analyse for each question. Use this in conjunction with your own supporting examples). Either 01: Discuss the idea that men and women use language differently. Or 02: Discuss the idea that the English language is changing and breaking up into many different Englishes. Either 01: Discuss the idea that speakers adapt their language to accommodate others. Or 02: Discuss the idea that representations of ethnicity in language are a concern. Either 01: Discuss the idea that certain accents and dialects carry prestige, whilst others do not. Or 02: Discuss the following statement: ‘political correctness is based on the idea that language doesn‘t just reflect social attitudes, but also helps to shape them.’ Either 01: Discuss the idea that only Standard English should be used in schools/the workplace, and any other varieties should be avoided. Or 02: Discuss Labov’s theory of language variation and change. Can it be applied to a modern speech community? Give examples to illustrate your points. 24 Assessment Objectives AO1: Apply appropriate methods of language analysis, using associated terminology and coherent written expression. AO2: Demonstrate critical understanding of concepts and issues relevant to language use. AO3: Analyse and evaluate how contextual factors and language features are associated with the construction of meaning. AO4: Explore connections across texts, informed by linguistic concepts and methods. AO5: Demonstrate expertise and creativity in the use of English to communicate in different ways. 25 AS Component Two Sample Question Discuss the idea that women and men use language differently. - In your answer you should discuss concepts and issues from language study. - You should use you own supporting examples and the data in Table 1, below. - Table 1 gives details of the turns, speaking time and interruptions at a staff meeting. (30 marks) Table 1 Speaker Average turns per meeting Average no. of seconds per turn Average ‘did interrupt’ per meeting Woman A Woman B Woman C Woman D Man E Man F Man G Man H Man I 5.5 5.8 8.0 20.5 11.3 32.2 32.6 30.2 17.0 7.8 10.0 3.0 8.5 16.5 17.1 13.2 10.7 15.8 0.5 0.0 1.0 2.0 2.0 8.0 6.6 4.3 4.5 Average ‘was interrupted’ per meeting 3.0 3.0 3.2 7.5 2.6 6.7 6.3 5.0 2.5 Source: B Dubois and I Crouch, ‘The question of tag questions in women’s speech: they don’t really use more of them, do they?’ ‘Language in Society, 4, 03, pp289-294. 26 AS Mark Scheme Extract – A02 AO2: Demonstrate critical understanding of concepts and issues relevant to language use. Level/Marks Level 5 17-20 Level 4 13-16 PERFORMANCE CHARACTERISTICS Students will: - Demonstrate an individual overview of issues - Assess views, approaches, interpretations of linguistic issues Students will: - Identify different views, approaches and interpretations of linguistic issues 27 INDICATIVE CONTENT These are examples of the ways students’ work might exemplify the performance characteristics in the question. They indicate possible content and how it can be treated at different levels. Students are likely to: Explore heterogeneity of female/male speakers Explain gender similarities hypothesis Explore other kinds of language use than spoken interaction Assess dominance and difference approaches explicitly Students are likely to: Illustrate effect of situation and use Illustrate effect of other characteristics of speakers: age, class, ethnicity Explore different interpretations of male/female conversational behaviours: e.g. tags as showing uncertainty or wielding power Illustrate research on gender and other variables: e.g. effect of status by Woods. AS Example Response There is a debate in the linguistic field that spoken interactions between men and women are characterised by miscommunication. There are linguistics such as Lakoff and Tannen who claim that there is difference in how men and women use language. This leads to the argument that perhaps it is miscommunication that forms a major characteristic between men and women’s spoken interactions. There are others however, such as Cameron, who disagree and claim that differences are exaggerated and focused on too much, for reasons other than language. Robin Lakoff identifies characteristics that were predominantly found in women’s language/ Lakoff suggested that hedges and fillers along with tag questions were found in women’s spoken language more than in men’s. It could be considered by men that women’s use of hedges, fillers and tag questions mean women are needy, talk too much and are indecisive. However, according to Lakoff, women talk less than men. It could be argued that the language features used by women show that they have an inferior social status to men. This is known as the Deficit Model and could be a reason for a possible miscommunication between men and women. Men could see women’s use of tag questions as indecisive, whereas a woman would see then as trying to get the man’s view on a subject and understand how he was feeling or what he was thinking. It is language features such as this which could lead to miscommunication and confusion between men and women. However, research conducted by O’Barr and Atkins on American courtroom trials found that many of the features identified by Lakoff to be ‘female’ were found in both men and women who were of low social status. This suggests that the language features Lakoff identified as being female were in fact found within individuals who are feeling powerless and not just ‘women’ on the whole. Lakoff’s ideas of women’s language features cannot be applied to all women and therefore may not be a clear indication as to why there may be miscommunications between men and women in spoken language use, as men are using some of the language features that Lakoff has branded as being a feature of women’s spoken language. Another feature of spoken language that could provide miscommunication between men and women is the issue of dominance. Men have a desire in mixed sex conversations to be seen as the dominant participant and have control of the conversation, including when people speak, how long they speak for and the topic of conversation. Men could do this by not taking up a women’s suggested topic of conversation and instead, putting their own topic across by interrupting the women, as Zimmerman and West found in their 1975 study. Conversations between men and women were recorded by Zimmerman and West and they found that 96% of all interruptions were made by men. They argue that this was a reflection of male dominance in society – something that Lakoff’s research also suggests. There is a common misconception that women interrupt more and do this to potentially show support to the person or people who they are in a conversation with. Beattie follows this view point but criticises Zimmerman and West by saying that men may not be interrupting to show dominance alone, but may be attempting to show some form of support and that they are listening to the conversation by saying things like ‘yeah’ and ‘mhummm.’ Interruptions can often be mistaken for something else within a conversation. They can be seen as an attempt to gain control and dominance but could actually be intended for the complete opposite, as Beattie reported. 28 Tannen takes the approach of describing men and women’s conversational style as being different, which could lead to miscommunication. Tannen, like Zimmerman and West, claims that men are concerned with dominance in a conversation and interrupt a lot to gain status. Women are the opposite to this and, according to Tannen, are far more interested in forming bonds with who they are talking to and so they agree more and talk less than men do. Another feature Tannen found was that men are more inclined to give direct orders such as ‘give me that’ and are not attempting to get away from any conflict. Women on the other hand, use more polite and indirect orders such as ‘would you mind giving me that please’ in order to avoid conflict and maintain positive face with who they are talking to. Men have no problem with breaking face in order to communicate with another person and communicate exactly what they mean. Tannen also notes that women show understanding and offer support rather than solution, whereas men are the opposite and want factual information. Men are more concerned with finding solutions. Women may see men as being emotionally unattached when engaging in a conversation, when in fact, it is simply just the way in which men communicate. The nature of how men and women converse can provide a large source of what could be described as miscommunication. Cameron would disagree entirely with Tannen and claim that research is biased and there has been a huge focus on the differences between male and female language, which is rather small, and not enough focus on the similarities. Language is used in everyday life and it is easy to sometimes mishear what people say or take what they have said in the wrong way. This is something that can lead to miscommunication and on top of that, there is the added issue of how men and women communicate differently which leads to another level of miscommunication. People can use language in a vulgar way to express how they are feeling or in a more articulate way. This suggests that language is not only a source of miscommunication between men and women, but also between different social classes. Working classes tend to speak with shorter sentences and think that they person who they are talking to shares similar experiences to them. The middle class however, tend to talk with longer, more complex sentences and so not assume that the person they are talking to has undergone the same experiences. Of course this is, like Lakoff’s research, highly generalised but is a set of generalised statements that can be applied to society. This shows that gender is not the only factor that is causing miscommunication between men and women, but also social status and class. Spoken interactions between men and women can lead to miscommunication for a number of reasons such as interruptions occurring, dominance being asserted and conversation starters not being taken up. There are different theories as to why this happens, along with the idea that men and women simply communicate in a different way which inevitably leads too miscommunication between the two sexes. However, it may never be fully and definitely understood by leading linguists as to why there is, at times, such miscommunication in spoken interactions between men and women. Perhaps the topic in itself is just misunderstood. 29