Acknowledgements - Department of Social Services

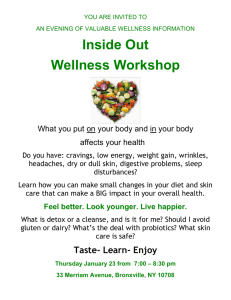

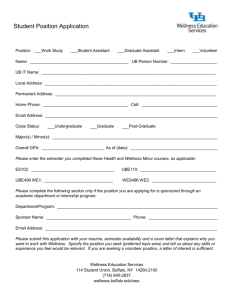

advertisement