PPP ZA - The British Chamber of Commerce in Zambia

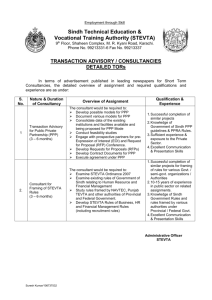

advertisement