********* 1 - IP

advertisement

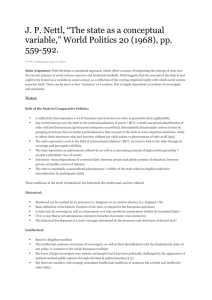

Governance and Crisis in the EU: Stateness trumps Europeanization? Kostas A. Lavdas Professor of Political Science and Director, KEPET, University of Crete lavdask@uoc.gr klavdas@alum.mit.edu GOSEM – 2 September 2013 – Draft I. In lieu of an Introduction Familiar approaches: neo-functionalism, federalism, liberal intergovernmentalism (IG), multilevel governance, new institutionalism, constructivism Taken for granted: some form of IG is crucial at junctures of EC/EU development Different sets of actors playing different roles during ‘routine politics’ and ‘emergency politics’ Today’s problem: ‘emergency politics’ extended over an unusually long period of time Neo-Functional- FEDERALISM ism Mechanisms Political features End state – telos? Spill-over / elite socialization / interest groups at EU level Security community/ political community Federalizing process / constitutionalism Separation of powers (e.g., Council of Ministers becomes Upper House…) Open-ended within A form of a a security federal-type union community framework MULTILEVEL LIB IG Mechanisms Policy-making in Logic of diversity/ networks at several main mechanism: tiers of authority/ two-level games multiple levels Political features Several tiers of authority / fluidity between tiers / authority becoming more dispersed Package deals / negotiating based on state preferences End state – telos? A form of multilevel governance Open-ended Three sets of challenges I. ‘emergency politics’ extended over an unusually long period of time II. the role of stateness in the EU III. the implications of the financial crisis for the institutional operation of the EU and the prevailing norms and rules of the game The remainder of this presentation will tackle these issues… II. Stateness as a conceptual variable Stateness involves a combination of the coercive capacity and infrastructural power of the state with a degree of identification on the part of the citizenry with the idea of the state that encompasses them territorially (Nettl) Scope/ extent, plus Strength/ power–effectiveness: I CAPACITIES Degree of collusion, Formation of policy goals: II AUTONOMIZATION Identification, rights/duties, expectations, efficacy / gaps: III POLIICAL OBLIGATION Table 3: Dimensions of stateness: capacities / autonomization Low capacities Developing capacities Collusion with actors / minimum institutionalization of state autonomy Asymmetrical development / partial – selective autonomy Variations on the patrimonial state model Exogenous (imported) institutions (GR 1) Historic forms of communist regimes Converging from paths of incomplete pluralism (GR 2) Converging from paths of bureaucratic authoritarianism Converging from paths of segmented pluralist Pursuit of societal goals / strategies through state policy Maximum capacities Historic forms of Scope + Strength authoritarian (Fukuyama) corporatism Maximum autonomy vis-à-vis interests/networks ? --- Approaches to the implications of EC/EU membership for stateness: I. ‘European rescue of the nation-state’ (Milward) II. Stateness in transformation through the ‘pooling of sovereignty’ (mainstream consensus) III. Asymmetrical transformations of stateness and an EU-embedded sovereignty (vide the diverse changes in the three dimensions of stateness: capacities, autonomy from interests, securing obligation by citizens) III. Europeanization and stateness before 2008 Europeanization is an interactive political, institutional and cultural process. A host of diverse processes which concern adaptation, adjustment, impact, interactions and feedback, beginning in anticipation of membership and expanding to more synchronized developments during later stages of full membership. A three- way process: (a) uploading preferences, (b) impact (of EU on national level) and ( c) interactions (between levels) and feedback Governments of member-states ‘upload’ their policies – whenever possible to reach agreements – to the European level, then use that level as a point of reference in order to minimize the costs in ‘downloading’ them at the domestic level. The ‘impact’ (of the EU on the national level) is conditioned by preferences AND capacities AND interests AND circumstances, irrespective of the source of such policies (even if ‘uploaded’ by same states) IV. A brief case study: Greece Since the 1980s, full membership in the EC/EU has offered Greece the possibility to form a new strategic sense of direction as well as burdening the country with testing challenges. As a result of rapid change, very real opportunities, and increasingly complex challenges, set against a background of inherited institutions and practices that were ill equipped to cope, Greece found itself at a prolonged juncture of stateness Successive Greek governments approached the EC / EU as a mechanism for extracting / securing resources in order to ( a) achieve domestic pacification (especially in the agricultural sector but also in troubled urban and semi-urban areas), ( b) serve the party-political and patronage-related needs of the political elites, and ( c) amplify Greece’s voice in foreign policy objectives and entanglements (Med, Turkey, Cyprus) No serious attempt to embark on a strategic effort to change the stateness paradigm through sustained purposeful action (modernize the bureaucracy, increase extracting capacities, introduce and implement new public management, etc) No serious attempt to embark on a strategic effort to modernize the political economy (apart from reactive moves - responses to the most direct and unavoidable challenges, e.g., to the banking sector) – no proactive approach Privatization represented a far-reaching change in the post-war statist policy paradigm. The choice for privatization resulted from stimuli and pressures associated with Europeanization. Privatization was most successful in the banking sector, with important broader implications for the entire economy. On balance, however, the limits of Europeanization before the sovereign debt crisis and its implications were considerable. In the years prior to the imposition of a new compliance regime by the EU – ECB – IMF, the Greek government’s ability to pursue its reform objectives was more constrained by entrenched interests at home than market pressures from the EU After 2002, with the euro, Greece enjoyed a boom based on cheap credit, because the bond markets no longer worried about high inflation or a devalued currency, which allowed it to finance large currentaccount deficits. Leading to a huge €350 billion public debt, half of it to foreign banks. There is a deeper, longer-term negative dimension: Both the transfers from the EU (since 1981) and the borrowed sums went mostly to finance consumption, not to saving, investment, infrastructure, modernization, or institutional development. Hence neither the domestic economy nor the prevalent form of stateness benefited from the transfer of funds. Today, Five years of unbroken recession, the end of rescue package coming in 2013: finance ministry says about €4.5bn will be needed in 2014 and another €5bn in 2015 – small compared to the package but will the EU shoulder the new loans? some form of debt relief will have to be discussed between the German elections (September, 22) and elections to the EP (May, 25) – but Greece will hold the presidency Social implications of the crisis: severe Military / defence implications: severe “Creative destruction”? Unclear yet, some positive signs: (a) exports on the increase, (b) forming a primary surplus. While Greece’s Europeanization has been an impressively persistent project, the extent to which future generations will approach it as a tenacious project or as an obstinate one (i.e., a project focused on a narrow-minded elite strategy bordering on self-deception) will depend on complex interactions between domestic and EU-level developments – a combination that’s difficult to predict. Even assuming the need for the rescue packages, the implementation was typical of Greece’s stateness characteristics: massive deflation but – initially at least – no structural reform, no effective tax reform, revenue collection lagging behind due to inability to tackle the shadow economy, extremely slow pace of privatizations Again, major shifts in the stateness paradigm did not occur as a result of strategic action In 2010, when the EU – ECB – IMF lending began, Greece’s stateness was still conceivable in terms of the embedded sovereignty exercised in the context of the EU, i.e., in the context of what the German Constitutional Court famously declared to be a ‘Staatenverbund’ (a compound of States, 1993 ruling on the Maastricht Treaty): ‘If a community of States assumes sovereign responsibilities and thereby exercises sovereign powers, the peoples of the Member States must legitimate this process through their national parliaments’ How to approach stateness in Greece, Portugal, Spain or Ireland since 2010-2011? In Portugal, Ireland, Italy, Spain and Greece from last year, the year-to-year reductions in the deficitto-GDP ratio have been unusually large and the resulting contractionary effects unusually severe, deepening the recession and increasing unemployment Despite the popular protests and frequent governmental crises, the recent and projected deficit-to-gross domestic product ratios of those countries continue, without exception, on their downward-sloping trajectories toward the target of 3 per cent. After five years to deep recession, Spanish conditions are ugly in some respects, somewhat encouraging in others (exports); yet austerity policies started a mass emigration last year and will continue to boost debt ever higher. Despite export performance, weak growth will contribute to lead to economic and political challenges. In Portugal, the recession will continue until 2014, and the unemployment rate will remain close to 20 percent. In July, the resignation of two ministers led to a new cabinet. There is talk of greater flexibility in austerity measures that would soften the contraction impact. In Greece, the contraction was 6.4 percent of the GDP in 2012 and will remain at 5 percent in 2013. The country will be in recession well over the mid-2010s, despite additional funding by Brussels. Unemployment close to 26 percent. Europe needs a short-term fiscal stimulus. There are only two ways to provide that stimulus: by allowing the countries in deep and protracted contractions and depression-level unemployment to suspend for the time being their pursuit of the 3 per cent target; and by inducing the countries – like Germany – that now have deficits under 3 per cent of GDP to undertake a fiscal stimulus that will boost domestic demand If it doesn’t happen, the eurozone will remain trapped in perpetual economic stagnation, frequent recessions and double-digit unemployment. Risking the ‘failing state’ syndrome In political science, the concept has been used to denote a state which is unable to maintain internal security and a degree of political order. Some (Chauvet and Collier 2008) give the term an economic meaning: “a failing state is a low-income country in which economic policies, institutions and governance are so poor that growth is highly unlikely. The state is failing its citizens because even if there is peace they are stuck in poverty.” The concept has been used in IR literature and debates to denote collapsed and/or severely incompetent regimes that need to be “fixed” by way of external assistance and/or the formation of transitional, shared sovereignty (Krasner 2004). Differences between a ‘failed state’ and a ‘failing state’ Could an EU member state with protracted failures in economic management and political efficacy be considered a ‘failing state’? It will partly depend on the evolution of EU governance and the future of federal-type features (Michigan – today – or California – a few years ago – would not qualify as ‘failing states’) IV. The crisis: lessons & issues The obvious: a monetary union is a permanent mess absent a degree of economic governance and polity-like predictability. Beyond that, six (6) issues (see Lavdas, Litsas & Skiadas and bibliography therein): 1) New precedents have been set with regard to the management of debt crises in the Eurozone, entailing the provision of IMF and European financial assistance, in combination with austerity and structural reforms. The template includes also bondholders being asked to participate in debt restructuring proceedings, with the possibility of incurring losses to their investments. 2) The exposure of the European banking system to the countries in crisis (Greece, Portugal, Ireland, Spain) caused serious concerns: it was thought that the crisis would be transmitted to the European financial sector, thus necessitating the conduction of “stress tests”, examining the capacity of the banks to absorb losses on distressed Eurozone bonds. The results were encouraging but the stringency of the tests has been questioned. Next: Banking union? 3) The bilateral loans provided by some of the Eurozone members to other members, as well as their participation in establishing the EFSF/ESM mechanism, caused increased financial liabilities for these states, as they have to meet their own debt problems, leading to a more careful treatment for these states in the international capital markets. 4) The crisis in the eurozone demonstrated the constraints imposed on members of a single currency area (i.e., the lack of authority to devaluate currency in order to boost exports and support growth generating activities), while, at the same time, it helped highlighting the fact that the denomination of the debt burden in a “hard” single currency prevents the increase of the debt’s values, if the use of another, devaluated “national currency” was allowed. 5) The entire scheme of EU economic governance was re-examined with a view to improve the effectiveness of the Stability and Growth Pact in terms of enforcement, by introducing greater surveillance of national budgets by the European Commission, and establishing an early warning mechanism that would prevent or correct macroeconomic imbalances within and between member states. The IMF became the external ‘enforcer’, but in the future? 6) The crisis in the eurozone has highlighted the limits of the EU integration process, as it revealed the fundamental disagreements between member states about how much EU integration is desirable, as well as the fact that certain member states still place their national interests above the ‘common interest’ in the EU. These limits have been countered (?) by the increase of formal and substantive authority of the European Central Bank as well as the creation of a permanent European lending facility. V. Now what? The norms that foster EU governance as a longer-term project in the making In IR, notions of reciprocity (returning good behaviour for good behaviour and bad for bad) are considered crucial for stabilizing cooperation by making noncooperative behaviour unprofitable The issue of the temporal horizon of cooperation: if it’s there (due to a historic background) how to secure its prevalence? Two basic patterns of reciprocity: *Specific reciprocity occurs when exchanges are seen as comparable in value and occur in strict sequence [in specific reciprocity, both actors in a relationship insist that the value of their concessions must be equivalent and that each must be made highly conditional on the other] * Diffuse reciprocity occurs when the actors consider both the value and timing of individual concessions to be irrelevant [main consideration: the long-term horizon of cooperation] BUT as Joseph Lepgold and others have suggested, there is evidence of stable, cooperative interaction in which exchanges fit neither of these patterns. Mixed patterns of reciprocal cooperation: we can identify four distinct patterns of reciprocity in terms of the two basic dimensions of social exchange on which it is based: contingency and equivalence. Contingency refers to the sequence and timing of an action taken by one actor in response to an action taken by another. A highly contingent action is one which is only taken in response to an action by another, and is taken fairly quickly thereafter Equivalence refers to a comparison of the perceived values of goods given and received. Theories of social exchange suggest that the value of any particular good is issue-, context-, and actor-specific and is not inherent to the good itself (rather than being a function of some objective value of the goods themselves, equivalence depends on how the exchange is subjectively evaluated) Patterns of reciprocity PATTERNS OF RECIPROCITY: Specific: Contingency / Equivalence: In strict sequence / Narrow equivalence Diffuse: Long-term / Broadly conceived equivalence Mixed: Mixed: In strict sequence / Broadly conceived equivalence Long term / Narrow equivalence Table 4. EU actors’ expectations in four strategic contexts (adapted from Lepgold and Shambaugh 2002). CONTINGENCY- IMMEDIATE LESS IMMEDIATE Precise Cell 1 Specific reciprocity: narrow exchange (perceived as equivalent in value) in strict sequence Cell 2 Mixed: narrow, longer-term exchange Imprecise Cell 4 Mixed: broad exchange in strict sequence Cell 3 Diffuse reciprocity: broad (perceived as non equivalent in value) and longer-term exchange Equivalence Cells 1 and 3 refer to the familiar cases of ‘specific’ vs. ‘diffuse’ reciprocity: Specific reciprocity occurs when exchanges are seen as comparable in value and occur in strict sequence. In other words, in specific reciprocity, both actors in a relationship insist that the value of their concessions must be equivalent and that each must be made highly conditional on the other. The polar opposite pattern (diffuse reciprocity) is one in which the actors consider both the value and timing of individual concessions to be irrelevant. Exchanges in this pattern are not expected to be strictly comparable in value or linked closely in time. Emphasis on the long-term horizon of cooperation. How do norms of intense cooperation form in today’s EU? And how does today’s EU (with its familiar projection of ‘soft power’ and ‘magnet quality’ capacities) influence international norms? In EU politics, at early points in cooperation, both actors demand strict contingency and precise equivalence from the other. As the horizon of cooperation expands, other modalities gain in weight, linked to diffuse and mixed models of reciprocity. The main hypothesis is that the concepts used (such as subsidiarity, codecision, and so on) depend on how actors interpret (and then respond to) others’ policy moves and policy concessions. Specific reciprocity (Robert Axelrod’s ‘tit-for-tat’ games) after the late 1940s can help explain the absence of violent conflict in European IR. Yet the institutionalization processes associated with the EC/EU can only be explained with reference to a combination of (a) strategic action aimed at expanding cooperation, (b) the prevalence of diffuse and mixed reciprocity games, and (c) an encouraging international environment. Not all games are linked to diffuse reciprocity; some correspond to the mixed types suggested by Lepgold and Shambaugh. Indeed, games linked to partially unbalanced relationships constitute much that is worthy of examination in today’s EU politics Theorizing reciprocity in regional contexts The types of reciprocity can help explain the different ways in which political theory establishes the relationship between the domestic and the international. In the Westphalian era, the clear distinction predominates, whereby the traditions of justice and the good life are considered to be relevant at the domestic level of analysis. The international level can at best accommodate specific reciprocity. Yet this is a process, uncertain and fragile, in which shifting modes of reciprocity may encourage or discourage further coexistence and cooperation. The stability or instability of reciprocity norms will decide the next steps. It is not accurate that all democracies refrain from fighting amongst themselves. It has been demonstrated that emerging democracies with unstable political institutions often associate themselves with both domestic and international violence and conflict. VI. Transition towards what? Recent evidence from the Eurobarometer indicates that we may be going through a transitory phase. The outcome may depend on a combination of particular policy choices in hard times and the prevalence of a longer-term horizon of cooperation as a priority Perversely, the EU’s demographic trends (an ageing population) may be considered helpful in this respect, absent a conscious, deliberative reinforcement of the idea of European integration being grounded on the quest for peace. Eurobarometer data indicate that the public in member-states that benefited from transfers (structural funds etc) tended to express its trust to the EU with percentages well above the ones for the national government – a feature that dropped only after 2010 (see analysis in Lavdas & Mendrinou 2012). This decline, as the EU average demonstrates, is indicative of a more widespread tendency that appears in the data of ‘contributing’ member states as well. It is in fact even more marked as a tendency in the old and older member states, such as France, Germany, but also Portugal, Greece, and Spain. These findings suggest less a tendency towards political cynicism than an increase in skepticism among the EU publics. The importance of this distinction cannot be overestimated: the emergence of skepticism is closely linked to questions of trust and accountability, not apathy and alienation. While cynicism tends to imply alienation vis-à-vis the institutions and/or arrangements concerned, skepticism tends to reflect various forms of criticism on the part of public vis-à-vis the institutions and/or arrangements, and may also involve issues of accountability which may relate to criticism of a pattern or, in some cases, the experience of failed expectations. The increase in skepticism indicates also the questioning of particular practices, the lack of swift and decisive response by EU institutions, and the prevalence of features that may prove transitory, Depending of further policies and on the existence of a strategic coherence that may help interpret these policies for EU citizens VIII. Stateness and EU Governance: three scenarios The first scenario (a rather depressing one): the good old ‘Italian model’ (extensive fragmentation of the party system, prevalence of a multitude of particularistic linkages, balkanization of the state, limited capacity to institutionalize politics and a resulting anomic division of political labour) may be coming back with a vengeance. At EU level, this means a prolonged period of stalled ‘transition’ while ‘multilevel governance’ survives as a framework for the interplay of the most powerful networks with minimal accountability. The second scenario: a federal-type system emerging in the EU, coupled with an evolving system of federal economic governance. An EU Consensus, gradually replacing the Washington Consensus? Requires an emerging European polity, albeit a composite one. Securing the long-term horizon of interactions appears to be the decisive way for the continuing and expanding predominance of games of mixed and diffuse reciprocity. It will have to come about as a result of a greater synchronicity of national and EU-level developments. The third scenario represents the retreat to the state. It signifies a particular type of a juncture of stateness leading to the reinvigoration of a host of inherited state attributes and modified capacities. At present, an emerging pattern of asymmetric developments suggest that stateness undergoes changes in different ways within the EU; it undergoes changes depending on inherited national structures and capacities, fiscal and financial situation, and political imbalances at EU level. In states like Greece, regression to direct national political control of monetary policy may result in a financial, fiscal and economic meltdown. IX. In conclusion, When discussing European governance after the financial crisis of 2008, it appears that stateness does indeed trump Europeanization in a dual sense – in terms of real-world politics and as a concept: The features of stateness appear to be resilient and may even instrumentalize Europeanization to reproduce themselves; while the transformations of stateness within the EU system are asymmetric, i.e., stateness in Germany, France, Portugal, Greece, or Italy undergoes change in different and – absent a fiscal and political union – not necessarily converging ways. An analytic emphasis on stateness is necessary in order to follow developments in the EU system, especially since – in a period of prolonged ‘emergency politics’ – the institutionally defined processes and rules are applied in selective and asymmetric ways and forms of intergovernmental negotiation have become dominant. Bibliographical references Aalberts, T. E. (2004), ‘The Future of Sovereignty in Multilevel Governance Europe – A Constructivist Reading’, Journal of Common Market Studies, 42. 1, 23-46. Alberg, M., L. Brock and D. Wolf (eds) (2000), Civilizing World Politics: Society and Community beyond the State, Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield. Alesina, A. and F. Giavazzi (2006), The Future of Europe: Reform or Decline, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Anderson, J. J. (2002). Europeanization and the Transformation of the Democratic Polity, 1945-2000. Journal of Common Market Studies, 40. 5, pp 793822. Börzel, T. A. (2002). Pace-setting, foot -ragging, and fence-sitting. Journal of Common Market Studies, 40. 2, pp 139-214. Bowman, J. (2006), ‘The European Union Democratic Deficit: Federalists, Skeptics, and Revisionists’, European Journal of Political Theory, 5 (2), 191-212. Chryssochoou, D., Tsinisizelis, M., Stavridis, S. & Ifantis, K. (2003). Theory and Reform in the EU, 2nd edition. Manchester: Manchester University Press. Cram, L. (2001). Governance ‘to Go’: Domestic Actors, Institutions and the Boundaries of the Possible. Journal of Common Market Studies, Vol. 39, No. 4, pp. 595–618. Fabbrini, S. (2007), Compound Democracies: Why the United States and Europe are Becoming Similar, Oxford: Oxford University Press. Featherstone, K. (2011). The Greek Sovereign Debt Crisis and EMU: A Failing State in a Skewed Regime. Journal of Common Market Studies, 49. 2., pp 193-217. Hooghe, L. and G. Marks (2008), ‘A Postfunctionalist Theory of European Integration: from Permissive Consensus to Constraining Dissensus’, British Journal of Political Science, 39 (1), 1-23. Krasner, S. D. (2004). Sharing Sovereignty: New Institutions for Collapsed and Failing States. International Security, Vol. 29, No. 2, pp 85-120. Lavdas, K. A. (1997). The Europeanization of Greece: Interest Politics and the Crises of Integration. London: Macmillan. Lavdas, K. A. (2005). Interest Groups in Disjointed Corporatism. West European Politics, Vol. 28, No. 2, pp 297 – 316. Lavdas, K. A. (2012). Theorizing Precommitment in European Integration: Mending the Constraints of Ulysses. European Quarterly of Political Attitudes and Mentalities, Volume1, No.1, pp. 10-25. Lavdas, K. A. and D. N. Chryssochoou (2011). A Republic of Europeans. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar. Lavdas, K. A., Litsas, S. & Skiadas, D. N. (2013). Stateness and Sovereign Debt: Greece in the European Conundrum. Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield. Lavdas, K. A. & Mendrinou, M. (2012). Contentious Europeanization and the Public Mind: Greece in Comparative Perspective. In P. Sklias et al., Greece’s Horizons. New York: Springer. Lepgold, J. and G. H. Shambaugh (2002), ‘Who Owes Whom, How Much, and When? Understanding Reciprocated Social Exchange in International Politics’, Review of International Studies, 28 (2), 229-52. Lütz, S. and M. Kranke (2010), The European Rescue of the Washington Consensus? EU and IMF Lending to Central and Eastern European Countries, LSE ‘Europe in Question’ Discussion Paper Series, 22/2010. Marks, G. et al. (1996), ‘European Integration from the 1980s: State-Centric v. Multi-level Governance’, Journal of Common Market Studies, 34 (3), 341-78. Marks, G. & Steenbergen, M. R. eds. (2004). European Integration and Political Conflict. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Nelson, R. M., Belkin, P., Mix, D. E. (2011). Greece’s Debt Crisis: Overview, Policy Responses, and Implications, Congressional Research Service - Report for Congress, R41167, 18 August 2011, p. 12-13. Nettl, J. P. 1968. “The State as a Conceptual Variable.” World Politics, 20: 559592. Pace, M. (2007), ‘The Construction of EU Normative Power’, Journal of Common Market Studies, 45 (5), 1041-64. Puchala, D. J. (2003), History and Theory in International Relations, London: Routledge. Rosamond, B. (2000), Theories of European Integration, Basingstoke: Macmillan. Scharpf, F. W. (1999), Governing in Europe: Effective and Democratic?, Oxford: Oxford University Press. Scheipers, S. and D. Sicurelli (2007), ‘Normative Power Europe: a Credible Utopia?’, Journal of Common Market Studies, 45 (2), 435-57. Schmitter, P. C. (1996), ‘Examining the Present Euro-Polity with the Help of Past Theories’, in G. Marks et al., Governance in the European Union, London: Sage, pp. 1-14. Schmitter, P. C. (2000), How to Democratize the European Union …and Why Bother?, Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield. Schmitter, P. C. (2010), ‘Citizenship in an Eventual Euro-Democracy’, Swiss Political Science Review, 4 (4), 141-68. Taylor, P. (2003). International Organization in the Age of Globalization, London: Continuum. Taylor, P. (2008). The End of European Integration: Anti-Europeanism Examined, London: Routledge. Weiler, J. H. H. (2003). In Defence of the Status Quo: Europe’s Constitutional Sonderweg. In J. H. H. Weiler and M. Wind (eds), European Constitutionalism beyond the State, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 723. Zalewski, M. (1996). All These Theories Yet the Bodies Keep Pilling Up: Theory, Theorists, Theorising. In S. Smith, K. Booth and M. Zalewski (eds), International Theory: Positivism and Beyond. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp.340-53.