Descriptive Research - Psychology 242, Research Methods in

advertisement

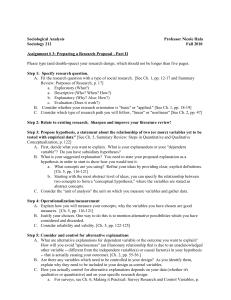

Foundations of Research 1 14. Descriptive Research This is a PowerPoint Show Open it as a show by going to “slide show”. Click through it by pressing any key. Focus & think about each point; do not just passively click. 60 % of participants 50 © Dr. David J. McKirnan, 2014 The University of Illinois Chicago McKirnanUIC@gmail.com Do not use or reproduce without permission 40 30 20 10 0 Any use Any freq. use Freq. Alch. Intox. Freq. Maj. Freq. 'Hard' drugs 0 - 1 Depresson symptom >2 Depression symptoms Chart: David J. McKirnan Foundations of Research What does Descriptive research do? Provides a basic overview of a behavior or status. “Who, what, where & when.” … In depth (qualitative) portrayal of a the behavior. Simple characterization of status groups… What % of adult men are unemployed… What is the divorce rate… Generate hypotheses Use qualitative or quantitative descriptions to begin asking “why?” or “how?” a behavior occurs. Develop hypotheses about how to change a behavior… 2 Foundations of Research Forms of descriptive research Qualitative or Observational Quantitative Describe an issue via valid & reliable numerical measures Study behavior “in nature” (high Simple: frequency Qualitative counts of key behavior ecological validity). “Blocking” by other variables Correlational research: “what relates to what” Complex modeling In-depth interviews Focus (or other) groups Textual analysis Qualitative quantitative Observational Direct Unobtrusive 3 Existing data Use existing data for new quantitative (or qualitative) analyses Accretion Study “remnants” of behavior Wholly non-reactive Archival Research Use existing data to test new hypothesis Typically nonreactive Foundations of Research Forms of descriptive research Qualitative or Observational Quantitative Describe an issue via valid & reliable numerical measures Simple: frequency counts of key behavior Correlational research: “what relates to what” Complex modeling Existing data Study behavior “in Use existing data for nature” (high new quantitative (or ecological qualitative) The mostvalidity). basic – and common – analyses form of description is simplyAccretion counting events. Qualitative “Blocking” by other variables 4 (We discussed Epidemiology and related studies in of In-depth interviews Study “remnants” Module 4). behavior Focus (or other) Typically frequency counts are groups Wholly non-reactive expressed as “rates”: Textual analysis Archival Research the percentage (or rate) of students Qualitative Use existing data to graduating in 4 years; quantitative test new hypothesis the divorce rate… Typically nonObservational Direct Unobtrusive reactive Foundations of Research 5 Forms of descriptive research Qualitative or Observational Quantitative Existing data Describe an issue via valid & reliable numerical measures Study behavior “in nature” (high Simple: frequency Qualitative Of course frequency Accretion counts are almost counts of key behavior ecological validity). “Blocking” by other variables Correlational research: “what relates to what” Complex modeling Use existing data for new quantitative (or qualitative) analyses In-depth interviews invariably “blocked” by other variables,of Study “remnants” behavior which(ormay include time period: Focus other) groups Wholly are 4 year graduation ratesnon-reactive similar for Textual analysis male and female students? Archival Research Qualitative is the divorce rategreater or lower Use existing data to quantitative test new hypothesis now than 20 years ago… Observational Direct Unobtrusive Typically nonreactive Foundations of Research 6 Forms of descriptive research Qualitative or Observational Quantitative Existing data Describe an issue via valid & reliable numerical measures Study behavior “in nature” (high Simple: frequency Qualitative Accretion We saw in the statistics section that counts of key behavior ecological validity). “Blocking” by other variables Correlational research: “what relates to what” Complex modeling Use existing data for new quantitative (or qualitative) analyses In-depth interviews correlations are basic measures of Study “remnants” of behavior association between variables. Focus (or other) groups Wholly non-reactive Rising divorce rates, for example, Textual analysis may be associatedArchival over timeResearch with Qualitative downturns, economic Use existing data to quantitative test new hypothesis As we have also seen, simply knowing Observational that two variables are associated often Typically nonreactive does not allow us to impute causality. Direct Unobtrusive Foundations of Research Quantitative Describe an issue via valid & reliable numerical measures Simple: frequency counts of key behavior “Blocking” by other variables Correlational research: “what relates to what” Complex modeling Click for a modeling overview. 7 Forms of descriptive research Qualitative or Observational Existing data Study behavior “in Use existing data for nature” (high new quantitative (or Correlational studies have the virtue of ecological validity). qualitative) analyses allowing researchers to consider many Qualitative Accretion variables at once. In-depth interviews Study “remnants” of As we have also seen, simply knowing behavior Focus (or other) that two variables are associated often groups Wholly non-reactive does not allow us to impute causality. Textual analysis Archival Research The model we Qualitative Use existing data to described in quantitative test new hypothesis Module 4 is an Observational Typically nonexample: reactive Direct We would test this model but running a Unobtrusive large(r) set of correlations. Foundations of Research Forms of descriptive research Qualitative or Observational Quantitative Describe an issue via valid & reliable numerical measures Study behavior “in nature” (high Simple: frequency Qualitative counts of key behavior ecological validity). “Blocking” by other variables Correlational research: “what relates to what” Complex modeling 8 In-depth interviews Focus (or other) groups Textual analysis Qualitative quantitative Observational Direct Unobtrusive Existing data Use existing data for Qualitative research: new quantitative (or qualitative) Addresses the analyses “lived experience” Accretion of behavior; Study “remnants” of behavior Analyses are from the inside out. Wholly non-reactive It is far less Archival Research concerned with Use existing data numerical or to test new hypothesis statistical analyses Typically nonthan rich reactive description. Foundations of Research Forms of descriptive research Qualitative or Observational Quantitative Describe an issue via valid & reliable numerical measures Observational studies: Simple: frequency counts A form of qualitative key research; behavior “Blocking” Directly observing by other behavior “in the variables wild” attempts to Correlational capture natural research: “what phenomena with relates to what” minimum alteration Complex or bias from modeling the researcher. 9 Study behavior “in nature” (high ecological validity). Qualitative In-depth interviews Focus (or other) groups Textual analysis Qualitative quantitative Observational Direct Unobtrusive Existing data Use existing data for new quantitative (or qualitative) analyses Accretion Study “remnants” of behavior Wholly non-reactive Archival Research Use existing data to test new hypothesis Typically nonreactive Foundations of Research 10 Forms of descriptive research Qualitative or Observational Quantitative Describe an issue via Study behavior “in “Accretion” research is a form of valid & reliable nature” (high observation, but of the remnants of ecological validity). numerical measures behavior. Qualitative Simple : frequency Many behavioral patterns leave counts of keythat can be counted In-depth interviews traces or behavior Focus (or other) described groups “Blocking” other Usingby such traces Textual analysis variables (e.g., counting pieces of drug Qualitative Correlational paraphernalia to determine where quantitative research: drug“what use is most common) Observational relatescan to what” provide relatively unbiased Direct Complex estimates modeling of behavior. Unobtrusive Existing data Use existing data for new quantitative (or qualitative) analyses Accretion Study “remnants” of behavior Wholly non-reactive Archival Research Use existing data to test new hypothesis Typically nonreactive Foundations of Research Quantitative 11 Forms of descriptive research Qualitative or Observational Describe an research issue viais increasingly Study behavior “in Archival valid & reliable important in a variety ofnature” fields. (high ecological validity). numerical measures Using data collected for another Simple : frequency purpose – such as Qualitative health records – counts of key In-depth interviews allows researchers to ask questions behavior that may be far tooexpensive as a Focus (or other) free-standing study. groups “Blocking” by other Textual analysis variables There are thousands of existing data Qualitative sources, from government data Correlational bases“what to dating webquantitative sites. research: Observational There is an increasing push for all relates to what” researchers to make their raw data Complex modeling Direct publicly available for archival Unobtrusive research. Existing data Use existing data for new quantitative (or qualitative) analyses Accretion Study “remnants” of behavior Wholly non-reactive Archival Research Use existing data to test new hypothesis Typically nonreactive Foundations of Research Forms of descriptive research Qualitative or Observational Quantitative Describe an issue via valid & reliable numerical measures Study behavior “in nature” (high Simple: frequency Qualitative counts of key behavior ecological validity). “Blocking” by other variables Correlational research: “what relates to what” Complex modeling 12 In-depth interviews Focus (or other) groups Textual analysis Qualitative quantitative Observational Direct Unobtrusive Existing data Use existing data for new quantitative (or qualitative) analyses Accretion Study “remnants” of behavior Wholly non-reactive Archival Research Use existing data to test new hypothesis Typically nonreactive Foundations of Research 13 Examples of descriptive data Simple description: how much alcohol and drugs do gay/bisexual men consume? 70 60 Very high rates of simple use Much lower rates of heavy use Drugs increasing, alcohol decreasing 1999 -> 2001 50 These simple frequency data provide a simple, “bird’s-eye view” of a key behavior. Assessing different levels of use allows us to provide a more nuanced description. 40 30 20 10 0 Ma Cra Alc C Me MD He Oth Da riju oca r yu t c oh M o h e k i r . A n sed ana ine ol i nto xic atio n Any, 6 mo. McKirnan, D., et al., 2001 community sample > 3 days / month Foundations of Research Examples of descriptive data; blocking variable More complex description: blocking alcohol & drug use by ethnicity. 40 35 % of participants 14 All ps <.01 except alcohol use. 30 25 20 Whites show more alcohol & drug use on most measures. Other ethnic differences vary by drug. 15 10 5 0 An ys ub s Al co tan ho l ce African-Am., n=430 Ma rij u Ot h an a er d ru g Latino, n = 130 Al -d ru g s s+ se “Blocking” the data by a demographic variable – here, ethnicity – tells a more subtle story. x White, n = 183 2001 Community data: Ethnic differences in frequent (> 3 days/month) drug & alcohol use. McKirnan, D., et al., 2001 community sample Foundations of Examples of descriptive data; Simple correlation of measured variables. Research Testing exploratory hypotheses in descriptive data: Drug use by Quasi - Depression Groups 60 Here the data are used to test the hypothesis that depression is associated with drug use. Participants are blocked (post-hoc) on a standard measure of depression: 0 or 1 symptom v. 3 or more symptoms. Men with more symptoms use all forms of drugs more often. All effects p<.005 50 % of participants 15 40 30 20 10 0 Any use Any freq. use Freq. Alch. Intox. 0 - 1 symptom Freq. Maj. Freq. 'Hard' drugs > 2 symptoms 0/1 symptoms n = 391, > 2 symptoms n = 289. “Frequent” > 3 days / month. Foundations of Research Forms of descriptive research Qualitative or Observational Quantitative Describe an issue via valid & reliable numerical measures Study behavior “in nature” (high Simple: frequency Qualitative counts of key behavior ecological validity). “Blocking” by other variables Correlational research: “what relates to what” Complex modeling 16 In-depth interviews Focus (or other) groups Textual analysis Qualitative quantitative Observational Direct Unobtrusive Existing data Use existing data for new quantitative (or qualitative) analyses Accretion Study “remnants” of behavior Wholly non-reactive Archival Research Use existing data to test new hypothesis Typically nonreactive Foundations of Naturally occurring events: Research 17 Correlational designs Testing hypotheses with simple correlations: Testing a neurocognitive basis for addiction: Correlational studies consistently show a strong association between “sensation seeking” and drug abuse Trauma theory of depression: Reports of childhood abuse correlate strongly with scores on a range of depression measures… Procedures: Correlational studies often rest on a careful selection of participants to reflect a target population (see: sampling). Reliable and Field studies with questionnaires or interviews pay considerable attention to developing measures that are: Valid. (see: surveys) Core virtues of correlational research: A more “Natural” look at how variables relate than is possible in an experiment. Since the researcher exerts less control over participants, there is (potentially) less reactivity than in experimental designs. Can model very complex phenomena Foundations of Research Does ice cream cause people to drown? Drownings This shows a simple correlation. How might you interpret these data? Ice cream consumption (scoops / day). 18 Foundations of Research 19 Correlation designs: Drawbacks & fixes Causality; a simple correlation may confuse cause & effect. Negative moods ? Marijuana consumption What causes what? Or are both causal arrows correct? Confounds!; an unmeasured 3rd variable may influence both observed measures. Levels of the neurotransmitter anandamide? ? Negative moods Marijuana consumption With any correlation a “variable you didn’t think of” [a Confound] may actually cause both of your observations. Dealing with confounds: Use complex measurements or samples to eliminate alternate hypotheses. Learn about anandamide. Foundations of Research Example of correlation design: Mothers’ earnings. Click for the Slate.com article. Does having a child earlier cause a woman to earn less? 20 Women who have a 1st child at age 24 v. 25 have 10% lower lifetime earnings: Lower base salary; Smaller raises x earning lifetime. What causes this? Main hypothesis: a simple correlation pattern Child at an earlier age Burden of earlier motherhood Poorer lifetime earning. Click for the original research report: “The Effects of Motherhood Timing on Career Path,” July 2011, Journal of Population Economics, 24(3): 1071–1100. Foundations of Testing causality in correlational data: Motherhood and income, 2. Research 21 Alternate 3rd variable hypothesis: Perhaps a woman who decides to begin a family earlier has less personal ambition or poorer job prospects. So, the age of 1st child may be less important than the mothers personality or values. Decision to have a child earlier. Woman’s personal characteristics (less ambition, poor job skills). Poorer economic performance. Test: Compare women who started at 24 to women who tried to start at 24, miscarried, started at 25. Hypothesis: Women who tried to start at 24 but failed should have ~ characteristics as those who successfully started at 24; With this specific comparison the 10% differential should go away. Data: Comparison still showed a 10% earnings decrement; the alternate hypothesis was not supported. Foundations of Testing causality in correlational data: Motherhood and income, 3. Research 22 Second 3rd variable hypothesis: Personal importance of motherhood: Women who get pregnant early may not value a career. Again, the burden the earlier childhood may be less important than the mother’s values. Earlier pregnancy Motherhood values Poorer economic performance. Test: women who had been trying to get pregnant since they were 23; some succeeded at 24; others at 25. Hypothesis: groups were ~ in “motherhood value”, time of pregnancy was random, 10% difference should be gone. Data: Comparison still showed a 10% difference; 3rd variable “value” hypothesis was not supported. Foundations of Research Testing causality in correlational data: Motherhood and income, 4. Bottom line: The simple correlation between age at 1st pregnancy & income suggests that having children earlier costs. Alternate 3rd variable hypotheses question whether the age of 1st pregnancy really caused lower economic performance. It could be women’s job skills or commitment …or the value she places on motherhood By testing & refuting alternate hypotheses the author supported her initial interpretation. 23 Foundations of Research 24 Complex correlations Testing complex hypotheses using correlations in descriptive data: Does drug use lead to risky behavior equally for everyone? Perhaps drugs risk primarily for people who are depressed. high Drug use Risk Depression low Drug use X Risk Foundations of Research 25 Using Correlations in Descriptive Data Testing the Interaction of depression and drug use on sexual risk. Effect of drug use on sexual risk, by depression group Substance use during MSM sex Overall risk with men .17, n.s. Overall risk with women Overall risk with men Overall risk with women Substance use during MSW sex .17, n.s. .43, p<.000 .57, p<.000 Overall alcohol & drug use ns .10, n.s. 263 -.04, n.s. 71 .35, p<.000 200 .37, p<.000 95 26 Foundations of Complex correlation analyses of measured variables 2. Research Men who are not depressed show low (non-significant) correlations between drug use and risk. Men with more depression have substantial (statistically significant) correlations between drug use and risk. Effect of drug use on sexual risk, by depression group Substance use during MSM sex Overall risk with men .17, n.s. Overall risk with women Overall risk with men Overall risk with women Substance use during MSW sex .17, n.s. .43, p<.000 .57, p<.000 Descriptive Research. Overall alcohol & drug use ns .10, n.s. 263 -.04, n.s. 71 .35, p<.000 200 .37, p<.000 95 Foundations of Research Complex correlations We cannot run an experiment where we manipulate depression or drug use… Correlation patterns allow us to test hypotheses about depression, drugs and risk that we could not bring into the lab. 27 Foundations of Research Forms of descriptive research Qualitative or Observational Quantitative Describe an issue via valid & reliable numerical measures Study behavior “in nature” (high Simple: frequency Qualitative counts of key behavior ecological validity). “Blocking” by other variables Correlational research: “what relates to what” Complex modeling 28 In-depth interviews Focus (or other) groups Textual analysis Qualitative quantitative Observational Direct Unobtrusive Existing data Use existing data for new quantitative (or qualitative) analyses Accretion Study “remnants” of behavior Wholly non-reactive Archival Research Use existing data to test new hypothesis Typically nonreactive Foundations of Research Experimental v. Observational research Click for the Stats with Cats Blog, a good discussion of correlation and causality. 29 Foundations of Research Qualitative research Key feature: Data are unstructured or “natural”. Assess participants’ own thoughts or descriptions. …i.e., rather than having them react to stimuli or questions imposed by the investigator. Collect data in participants’ own environments, using observational of other field studies. Less influenced by researchers’ hypotheses or structured measures. Key uses: “Ground” research in the every-day reality of people. Describe the social or physical context of a behavior. Generate hypotheses. Provide a deeper understanding of lab or quantitative findings. 30 Foundations of Research Approaches to qualitative data Open-ended narratives Minimally structured interviews or writing samples: Typically face-to-face, but may also use written web-based narratives; Can range from relatively brief to very extensive; Centers on a general topic: …describe how things were with your family when you lived at home…, …and typically has a “look-back” or time line structure: …begin with your earliest memories, and take us to the present…. 31 Foundations of Research 32 Approaches to qualitative data Open-ended narratives Structured / guided description Qualitative or semi-structured interviews Face to face (doorstep) or telephone interviews Employs open-ended questions, often with some structured items as well. The interviewer conducts a guided analysis of behavior to “deconstruct” an event or behavioral pattern… Take me through the last time you drank any alcohol… What day was it? Time? Where were you?, what was the place like? Who were you with … family? Friends? Boy/girl friend? Strangers? What were you doing / what was going on… …etc. Foundations of Research 33 Approaches to qualitative data Open-ended narratives Structured / guided description Qualitative / semi-structured interviews Focus groups Often highly structured around a single theme or “focus”. Often combine open-ended discussion with more specific prompts that all participants respond to. Samples may be intentionally diverse, or relatively narrow (e.g., cancer survivors…). Click for a ‘how to’ for interviews & focus groups Foundations of Research 34 Approaches to qualitative data Open-ended narratives Structured / guided description Textual analysis Computer or expert raters analyze existing text; e.g., political writings, therapy transcripts, correspondence. Analyses of “found text”; e.g., diary entries, suicide notes. Foundations of Research 35 Approaches to qualitative data Open-ended narratives Structured / guided description Textual analysis Click for a concise list of 15 different types of qualitative analyses. Common denominators among qualitative methods: Discovery; Phenomenological perspective; Categorizing and clumping; Seeking associations. 36 Foundations of Research Approaches to qualitative data Open-ended narratives Structured / guided description Textual analysis Types of qualitative analyses. Common denominators among qualitative methods: Discovery; A core purpose is typically uncovering patterns of behavior or culture that we were unaware of, e.g., Goodall’s discovery of tool use in Chimps. This contrasts with much of experimental research, which hinges on a specific, theory-driven hypothesis. 37 Foundations of Research Approaches to qualitative data Open-ended narratives Structured / guided description Textual analysis Types of qualitative analyses. Common denominators among qualitative methods: Discovery; Phenomenological perspective; A central virtue of qualitative analyses is that they allow us to explore the participants’ own perspectives on their behavior or social world. Qualitative methods try to unveil the meanings and important issues of the participants’ lives, rather than addressing topics or meanings developed by the researcher. E.g., what are the “meanings” of friendship status on Facebook? 38 Foundations of Research Approaches to qualitative data Open-ended narratives Structured / guided description Textual analysis Types of qualitative analyses. Common denominators among qualitative methods: Discovery; Phenomenological perspective; Categorizing and clumping; Typically the first step in analysis is to categorize the data into themes, common threads that recur across or within participants. Themes may be discovered in the data, by noting common phrases or images, …or may be tested by searching for topics initiated by the researcher. Once themes are articulated the data are organized around them to explore their meanings. 39 Foundations of Research Approaches to qualitative data Open-ended narratives Structured / guided description Textual analysis Types of qualitative analyses. Common denominators among qualitative methods: Discovery; Phenomenological perspective; Categorizing and clumping; Seeking associations; Software programs can discover (or test) associations among themes, to explore how psychological processes may be related. Of course in some data – i.e., video – associations are dependent on investigator’s subjective analysis, which introduces bias. E.g., how often are citation of “friendship” in Facebook content associated with social support, emotional support, sexuality… Foundations of Research 40 Approaches to qualitative data Open-ended narratives Structured / guided description Textual analysis Common denominators among qualitative methods: Discovery; Phenomenological perspective; Categorizing and clumping; Seeking associations; One use of qualitative methods is to facilitate (or interpret) quantitative research. Testing or exploring associations often yields quantitative results, e.g., simple frequency counts of links in the data. More systematic studies address that link directly… Foundations of Research 41 Example of qualitative - quantitative research: Rafael Diaz’s study of stimulant use among Latino gay/bisexual men. Empirical questions: What % of Latino gay men use stimulants? Methamphetamine Cocaine Other What does stimulant use “mean” for men? – what are their motives or understandings? How does the meaning of drug use differ for meth v. cocaine? How do these concepts and attitudes affect drug use? Sexual or other risks & harms? Amount of drugs? Foundations of Research Diaz’s larger project had three central steps: 1. 2-hour qualitative semi-structured interview with 70 drug-using Latino gay men: Detailed qualitative description of drug use & sexual activity behavior social contexts reasons for use perceived effects Narratives on specific episodes of drug use with and without sexual activity with and without condom use. 2. Used qualitative findings to develop and test a survey instrument Different dimensions of stimulant use Relationship between stimulant use and HIV risk. 3. Administered revised survey to random sample of Latino gay men (n=300) who reported stimulant use. Click for the complete report 42 Foundations of Research Diaz study: qualitative findings Positive reasons for using meth / speed: Energy We each did a line of crystal because I was feeling sleepy. I was yawning. It wasn’t that I didn’t want to go out, I think I was physically just exhausted from the week. It was just long, and so that kind of gave me a boost of energy. I feel like invincible, you have so much energy, you can do anything you want…you can have a h_ _ _-on that goes for six hours… Youthfulness, attractiveness [With crystal] I find that I am no longer pudgy and plump. I feel that I’m a little bit more physically attractive because I’m not overweight. When you have AIDS, you feel like you’re slowing down and you’re losing all your senses, ok? And speed brings them all back and it makes me feel like I’m 16, 17… When you’re 16 or 17 years old you feel like you are invincible. 43 Foundations of Research Sexuality Diaz study: qualitative findings, 2, Positive Reasons I felt like it rushed to my brain, I felt my skin get hot and I felt the desire to have sex with whomever was around… Sex is better, much better... I go for like nine hours. It’s more passionate... the intensity, it makes me feel incredibly well. Sexual disinhibition I become even more hardcore. Sexual risks and inhibitions are totally gone. I become empowered in feeling, like I can take on the world or anyone that f_ _ _ed with me. It can be an euphoric rush. Sexual risk With drugs you start degenerating and you no longer are satisfied with one person…you want another and you want more and you want them all at the same time. So I do see a relationship, drugs do lead to becoming infected with diseases 44 Foundations of Research Diaz study: qualitative findings Negative consequences of meth / speed: Paranoia That also makes me want to stop because I have been feeling this horror of someone who is following me, uh… who wants to kill me or that is hiding but is following me. Social isolation … I was in another world... where at times you lose all shame, you lose friends, family, you lose... everything. Sometimes I wouldn't even make a phone call, all I cared about was getting high and that was it. Physical depletion I feel so gross that I can’t wash it off anymore. It’s like you feel like this inside dirty, like because there’s no food in your stomach for the past days, you’ve been just like running on empty and like you’re really gaunt now because you’ve been in a constant workout. 45 Diaz study: Quantitative analysis of qualitative findings Foundations of Research Develop conceptual categories by coders using the qualitative data. Then go back and have the computer search each interview for key words to count the % of men who mentioned each topic We can then use quantitative analyses to test hypotheses about differences between drugs… 46 Diaz study: Quantitative phase Foundations of Research 1. In the qualitative phase participants made many references to social facilitation or social integration. 2. This was one of the clear themes from the qualitative phase. 3. We quantify these themes by using phrases or references from the qualitative phase to create quantitative closed-ended survey items Diverse statements referring to social integration are coded into a larger category of “Social Connection”. Taking direct quotes, the researches turn this category into four “closedended” (numerical) rating scale items. Meth makes me feel… …not left out …more connected… Descriptive Research. 47 Foundations of Research 48 Diaz study: Quantitative phase Using the qualitative themes to create quantitative survey items: There were many references to emotional facilitation, stress reduction and the like in the interviews. These were all coded as “Coping with Stress”. Again, using key words from the interviews or representative text, the theme is turned into a set of closed-ended survey items Meth helps me… …forget my problems …take a break from a difficult situation… Descriptive Research. 49 Foundations of Research 1. Use repeated phrases or references from the qualitative phase to create quantitative closed-ended survey items 2. We then administer the quantitative survey to a much larger sample of men. Larger samples are typically more representative of the larger population than are the smaller samples we gather for qualitative interviews. Turning the themes participants described in Phase 1 into numerical survey items allows us to go beyond simple description toward hypothesis testing. Here n = 286 participants. Descriptive Research. Foundations of Diaz study: Qualitative findings, 2 Examining many categories of impacts weQuantitative can see that: Research Many stimulant users have important negative life effects, Significantly more so for meth. than for cocaine. 50 51 Foundations of Research 1. Use repeated phrases or references from the qualitative phase to create quantitative closed-ended survey items 2. Administer the quantitative survey to a much larger sample of men. 3. With quantitative data we can use statistical tests to: Ensure the items are reliable and internally valid; Test theory-driven hypotheses about drug use and personal harms. Here we use a correlational technique called Factor Analysis to test whether items that are supposed to represent the same concept actually cluster together. Descriptive Research. Foundations of Research Typically uses direct interviews, focus groups.. Structured: specific questions driven by research topic or hypothesis Semi-structured: general / probing questions guided by general topic Summary: Qualitative research Unstructured: “personal biography”; completely person centered. Important primary data source: Direct, in-depth measure of behavioral process Less biased by researcher’s hypothesis than a survey Important step in quantitative research: Generate hypothesis or theory of new phenomenon Produce externally [ecologically] valid qualitative assessments 52 Foundations of Research Forms of descriptive research Qualitative or Observational Quantitative Describe an issue via valid & reliable numerical measures Study behavior “in nature” (high Simple: frequency Qualitative counts of key behavior ecological validity). “Blocking” by other variables Correlational research: “what relates to what” Complex modeling 53 In-depth interviews Focus (or other) groups Textual analysis Qualitative quantitative Observational Direct Unobtrusive Existing data Use existing data for new quantitative (or qualitative) analyses Accretion Study “remnants” of behavior Wholly non-reactive Archival Research Use existing data to test new hypothesis Typically nonreactive Foundations of Research Observational Research 54 Assess behavior directly rather than by participants’ selfreports or recall: Typical data collection is highly reactive: participants know they are being studied, and react to that. Social desirability responding, for example, leads people to present themselves in a flattering – and perhaps inaccurate – light. Have you ever cheated on an exam? How often do you lie? “Stereotype threat” is a syndrome where peoples’ fear they may confirm a negative stereotype about their group leads them to perform more poorly. E.g., women and math… In interview or questionnaire studies participants may try to guess the hypothesis and support or refute it. Observational methods are often less (or non-) reactive. Click for a review of observational studies. Foundations of Research 55 Observational Research Assess behavior directly rather than by participants’ selfreports or recall. Directly observe the social & physical settings or environments of behavior: Observational research “grounds” the study in the actual physical and social settings where it naturally occurs. Key uses are similar to qualitative research: “Ground” a research approach in peoples’ everyday reality. Describe the social or physical context of a behavior. Generate hypotheses for further, more structured or even experimental research. Provide a deeper understanding of a set of lab or quantitative findings. Click to test your own observational ability Foundations of Research 56 Observational Research Assess behavior directly rather than by participants’ selfreports or recall. Directly observe the social & physical settings or environments of behavior. Investigate issues that could not practically or ethically be studied in an experiment: “Natural history” studies of disease progression; Complex social dynamics What are the status patterns in an elementary school classroom? Patterns of Illicit or illegal behavior; How does a “crack house” or “shooting gallery” actually work? What are the actual processes of gang initiation? Foundations of Research 57 Observational Research Observational methods differ in the amount of structure they impose; As with all research, there is a tradeoff of internal vs. external validity. More structured data are easier to interpret, yielding higher internal validity; That very structure may make such studies more “artificial”, potentially lessening external validity. More naturalistic data usually provide the most external validity. By not affecting or controlling participants’ behavior the results are less reactive. The interpretation of a large corpus of observational data – text, video, field notes – can be uncertain, and can be influenced by the researcher’s biases. Foundations of Research 58 Observational Research Observational methods differ in the amount of structure they impose; As with all research, there is a tradeoff of internal vs. external validity. Naturalistic observation; Controlled, unobtrusive observation; The researcher creates conditions to observe or shape behavior; Participants often do not know they are in an experiment. Clinical observation / case studies; The least structured, most “open” form of study. Of course case notes can be very reactive, although still informative More subtle variables – such as specific word choice, or posture – can illustrate basic processes with a minimum of reactivity. Participant observation; Here the researcher actually joins and participates in a social setting, and uses that experience to describe the process. Foundations of Research 59 Observational research: methods Naturalistic observation; visual observation & note taking or recording. Very direct data collection method Potentially strong reactive effects under some conditions. Charles Darwin’s observations of bird adaptations on the Galápagos Islands – which led to the theory of evolution – is an example of a groundbreaking, systematic observational study. Jane Goodall’s studies of Chimpanzees is perhaps the most famous – and groundbreaking – of such studies. She made critical discoveries, such as primate tool use. Her studies were criticized, however, because she fed and interacted – and even had emotional bonds – with her subjects. ShutterStock Click for an excellent National Geographic retrospective of Jane Goodall’s work. Foundations of Research 60 Example of naturalistic research A naturalistic observational study by researchers at Boston Medical Center in 2014 examined smartphone use by parents when eating with kids. Shutterstock.com Click for the ABC News report. Researchers visited 15 restaurants to surreptitiously observe parents’ behavior with their children. By the authors’ report Parents in 40 of 55 families were “absorbed in their mobile devices” during the meal. The operational definition of “absorbed” was not clear from the study. Many children were observed to display potentially disruptive behavior to get their parents’ attention. This study illustrates both virtues and problems of naturalistic research. The study was wholly non-reactive; had parents been given a questionnaire it is doubtful they would have reported their phone use accurately. Measurement and interpretation of key variables – such as “absorbed” – are ambiguous and subject to error or researchers’ biases. Foundations of Research 61 Observational research: methods Structured, Unobtrusive observation; Participants are unaware of data collection, but are responding to a structured situation or set of cues; In 1951 Solomon Asch showed that conformity pressure has a huge effect on behavior (See his experiment here). His participants’ knew they were in an experiment, but it has have been replicated many times using the “elevator paradigm” and others. ShutterStock The “lost letter” technique – initiated by Stanley Click image for a video of an elevator conformity experiment Milgram – is an easy, but unobtrusive way to gauge from Candid Camera. attitudes. o Researchers address stamped letters to different organizations, say, atheist vs. Christian groups. o They then “lose” them by dropping them randomly on different streets. o The outcome measure is how many letters are returned to each address Click for a YouTube clip (…letters addressed to Christian groups are returned muchdemonstrating more oftenthethan are use of an elevator to test conformity, those to atheists). Foundations of Research 62 Observational research: methods Structured, Unobtrusive observation; Participants are unaware of data collection, but are responding to a structured situation or set of cues; Walter Michel’s Marshmallow study is one of the most famous in all of Psychology. Michel hypothesized that people who could delay gratification as children – who had internal coping mechanisms – would do better as adults that would those who could not delay gratification as a child. How to test that? o Michel placed children alone in a room, and gave them a marshmallow. Click for a video of kids in the Marshmallow study o He instructed them that if they could keep from eating it for 15 minutes they would get an extra one. o As it turns out, those who could delay were doing a lot better after 20 years than those who were not able to delay. ShutterStock Foundations of Research 63 Observational research: methods Structured, Unobtrusive observation; Participants are unaware of data collection, but are responding to a structured situation or set of cues; ShutterStock Walter Michel’s Marshmallow study is one of the most famous in all of Psychology. This ingenious study assessed a key psychological variable in a completely non-verbal fashion. It combined structured observation with a longitudinal design; by following participants for 20 years with measures of occupational and psychological status, Michel was able to clearly demonstrate the effects. There may be some other variables operating that Michel did not assess; o Children who are led to believe they are in a trustworthy environment wait some 4 times longer than do those in an unreliable environment. o This is always an issue with observational research; o The measures are less structured, so we can never ensure that there are not other key variables operating. Foundations of Research 64 Observational research: methods Structured, Unobtrusive observation; Participants are unaware of data collection, but are responding to a structured situation or set of cues; Unobtrusive studies can use strong experimental manipulations to test hypotheses. Click the image for a great example of structured field research. This tests the “bystander effect” – lower willingness to help people when in a group – using an actor in a natural context. ShutterStock The question is “under what conditions will people help someone in obvious distress”. This study shows the power of structured observation; o the researchers manipulated different conditions of the experiment, o All the while keeping the study unobtrusive. They combined that element with brief interviews after people had gone through the manipulation. Foundations of Research Observational research: methods Structured, Unobtrusive observation; Participants are unaware of data collection, but are responding to a structured situation or set of cues. Participants are aware that they are in a research study, but the measures are unobtrusive enough that reactivity is minimized. Focus groups, either observed and recorded directly or through unobtrusive devices or 1-way mirrors are very common. o These are used in market research, qualitative research, and the preliminary stages of more traditional research. Shutterstock.com Simply “staking out” an environment, such as observing drug transactions to characterize that trade. Therapy research using one-way mirrors. 65 Foundations of Research 66 Observational research: methods Participant observation; becoming part of social phenomenon to describe it. Highly immediate and compelling description High potential bias in reporting and description Potential ethical concerns; other participants are invariably deceived, and potentially compromised. In 1967 Hunter S. Thompson joined and rode with a chapter of the Hells Angels, to write a 1st person account of that culture. • • Click here for the original, 1967 New York Times review. Click here for an excellent observational study of bisexual AfricanAmerican men on the “Down Low”. Click for Amazon order page. Foundations of Research Forms of descriptive research Qualitative or Observational Quantitative Describe an issue via valid & reliable numerical measures Study behavior “in nature” (high Simple: frequency Qualitative counts of key behavior ecological validity). “Blocking” by other variables Correlational research: “what relates to what” Complex modeling 67 In-depth interviews Focus (or other) groups Textual analysis Qualitative quantitative Observational Direct Unobtrusive Existing data Use existing data for new quantitative (or qualitative) analyses Accretion Study “remnants” of behavior Wholly non-reactive Archival Research Use existing data to test new hypothesis Typically nonreactive Foundations of Research Existing data 68 Accretion; Study remnants of behavior Data wholly unobtrusive Campbell & Webb: Field Museum studies: determine popularity via linoleum flooring, nose-prints on glass… HIV prevention studies: # used condoms in “lovers lane” area after a public health media campaign. http://sti.bmj.com/content/79/1/78.1.short Indirect; may only partially map onto phenomenon. Archival; data collected for other purposes Often in highly reliable, large & rich data sets Provide unbiased correlations, but most be adapted to new purpose or hypothesis (may not “map on” fully..). Northern European health records; effectiveness of mammography in lowering breast cancer Correlation of suicide rate and publicity about prominent suicides to test modeling effects. 69 Foundations of Research Can a program to provide support to High School Freshman increase 4/5 year graduation rates? Chicago Public Schools introduced “Freshman On Track” in 2011. The figure shows archival, time series data on graduation rates, 2008-2014 These are Archival data: researchers used existing data on graduation rates. The data are Time Series, allowing them to test change over time. The key contrast is before v. after the introduction of the program in 2011 Click image for the report. Graduation rates clearly increase after 2011, suggesting success for the program. Foundations of Research Archival descriptive data; Chicago High School graduation rates 70 Testing the Freshman On-Track Program. The On-Track program was system-wide; every school received the program. As a consequence, there is no Control Group. Click image for the report. What possible confounds are there in this design? • How can we really be sure change was due to the program? It is most plausible that increasing rates are due to the intervention… …without a control group we can never be 100% certain. Click for a summary from US News & World Report Foundations of Research 71 Archival data sources… Beyond obvious archival data sources… Click for analyses of singles in America by Match.com Educational tracking.... Uniform crime rates… Medical data… …many other, surprising data sources have emerged; Internet services collect and store massive amounts of personal data, which can be mined for analysis. o Consumer sites, of course, collect surprisingly detailed data. These are used by marketers to target ads… But also are used by economists to test hypotheses about consumer behavior generally. o Relationship matching sites now employ behavioral scientists, To hone their matching capabilities… …and as descriptive (and hypothesis testing) research data. o Even internet pornography sites are using their customer data to test research hypotheses. Foundations of Research Weird archival research example. Do frustrated people view pornography to feel better? Data from the 2014 Seattle – Denver Super Bowl. Baseline porn traffic is similar for the 2 cities Traffic lessens in both cities as the game begins Immediately after the game traffic is much higher among Denver fans Longer after the game traffic evens out As Denver begins losing badly traffic increases, particularly for Denver fans Click image for article. 72 Foundations of Research 73 Weird archival research example. Do frustrated people view pornography to make themselves feel better? Data from the Super Bowl. The overall viewing patterns suggest that more fans of a badly losing team view porn as the game goes on… To make themselves feel better? As a simple distraction? An alternate hypothesis is that people in Denver simply watch more porn. This is not plausible: traffic in the two cities was the same before and after the game. Of course a data pattern such as this cannot clearly answer “why”. It was not collected to test a hypothesis (obviously…) Foundations of Research O.K. Cupid; Attractiveness & Desirability 74 What makes a women attractive to men? On OKCupid… Does simple attractiveness lead to more messages? Or is there something more complicated? The women in these two pictures get similar attractiveness ratings, 3.4 v. 3.3 The picture on the left has a normal distribution, peaking at ‘4’. The picture on the right has a bimodal distribution: lots of both ‘1’s and ‘5’s. Foundations of Research 75 Attractiveness & Desirability What makes a women attractive to men? On OKCupid… Simple attractiveness does not by itself lead to more messages ✓ The woman with more complex or diverse ratings gets 2.3 times the average number of messages… The women with less diverse ratings gets only .8 times the average. ç ç This is despite their being rated as similarly attractive. Foundations of Research 76 Attractiveness & Desirability This finding is tested more scientifically by deriving the Standard Deviation (S) of 8 women’s attractiveness ratings, that is, the variance in how she was rated. All the women in this chart were about the 80th percentile in attractiveness. The amount of variance in each women’s ratings (not her overall attractiveness) is correlated with the number of messages she got. Foundations of Research 77 Attractiveness & Desirability All the women in this chart were about the 80th percentile in attractiveness. Women with higher deviation scores, i.e., both ‘1’s and ‘5’s … … elicited more messages than did women with more consistent scores, i.e., mostly ‘3’s and ‘4’s Perhaps simple attractiveness is not as interesting as being challenging. Foundations of Research Archival / “found” data What is common to these examples is that the data were not collected for research. They stem from tracking customers, uniform drop-out rates, etc. The data are “repurposed” to answer a research question. 78 Foundations of Research 79 Overall Descriptive Design Issues Time frame Cross sectional Simultaneous measure of all study variables. Good for simple description Major problem for correlations: Longitudinal Causal direction: Which caused which? Major 3rd variable threat (ice cream and drowning). Cohort or panel study; follow participants over time. Best for testing hypotheses; assessing over time helps determine cause & effect. With archival data powerful description of behavior (e.g., crime rates, health status in population x time). Case study Single or multiple n = 1, cross-sectional or longitudinal Foundations of Research 80 Descriptive methods: design issues, 2 Sampling See: Lectures 6, sampling Random or Probability Individual; e.g., random digit dial, voter registration list. Systematic; proportion of listed population Stratified; random with population sub-blocks, e.g., gender, ethnicity, Cluster; random within chosen (potentially convenience) clusters, e.g., within specific locations, census tracks, events. Multi-stage; random selection of population unit (households, blocks...), then random selection of individuals within unit. Non-Probability Convenience; Haphazard sampling within venues or settings frequented by target population. Stratified; convenience sample with population quotas Targeted; by key population, e.g., describe heroin addicts… Multiple frame; Multiple sources for unusual / rare participants Snowball / Social Network Referrals of new participants by current participants; useful for “hard to reach” people. Foundations of Research Descriptive methods: design issues, 3 Reactive measurement Participants (people or animals) react to the knowledge that they are being measured. Represents confound if responses are reaction to measurement rather than process under study Reactive bias increases with.. Clarity (face validity) of measures Face-to-face interview methods Often lessened with computer interviews 81 Foundations of Research Test - retest; Descriptive research issues, Reliability similar responses over time? Assume stable attribute; e.g., “personality” disposition If measure is reliable, should show similar scores across assessments Split-half; similar responses across item sets? Assume redundant / converging items or scales If scale is reliable, each half should yield similar scores Chronbach’s alpha; overall internal reliability Converging items should inter-correlate. 82 Foundations of Research Scale appears to measure what it is designed to E.g., interview item; “How dependent are you on heroin?” Simple skill index; assess computer skills by writing program Intuitively valid; clearly addresses topic May yield socially desirable responses. Content validity Validity Face validity Descriptive research: Assesses all key components of a topic or construct: e.g., the various components of complex political attitudes… Mid-term; test all core skills for research design… Predictive validity Validly predicts a hypothesized outcome: e.g., I.Q. is a moderately good predictor of college success, criminality, etc. A measure may be predictive valid without being face or content valid: the MMPI. 83 Foundations of Research Descriptive research: Validity (2) 84 Construct validity Test whether the hypothetical construct itself is valid (differs from other constructs, corresponds to measures or outcomes it should..). Test if the Measure addresses the construct it was designed for E.g.; “anxiety” and “depression” and “anger” may not be separate constructs, but may all be part of “negative affectivity”. e.g., measures of social support (“do you have people who care for you”) often strongly influenced by depression, a separate construct… “Ecological” validity Measure corresponds to how the construct “works” in the real world External validity of assessment device. Foundations of Research 85 Summary Qualitative or Observational Quantitative Describe an issue via valid & reliable numerical measures Study behavior “in nature” (high Simple: frequency Qualitative counts of key behavior ecological validity). “Blocking” by other variables Correlational research: “what relates to what” Complex modeling In-depth interviews Focus (or other) groups Textual analysis Qualitative quantitative Observational Direct Unobtrusive Existing data Use existing data for new quantitative (or qualitative) analyses Accretion Study “remnants” of behavior Wholly non-reactive Archival Research Use existing data to test new hypothesis Typically nonreactive Foundations of Research 86 Descriptive Research: Overview Basic design issues: Time frame Cross sectional Longitudinal Case study Reliability Test – retest Split – half Alpha (internal) Validity Face Content Predictive Construct Ecological