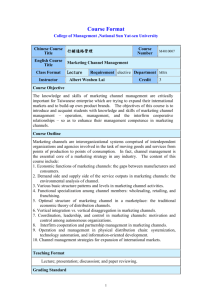

Appendices

advertisement