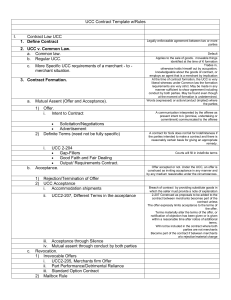

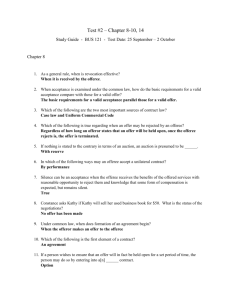

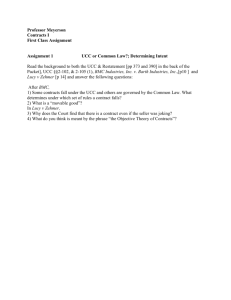

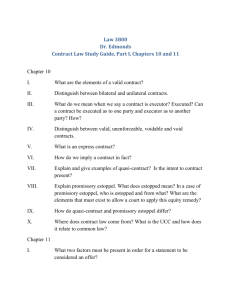

Contracts II 13

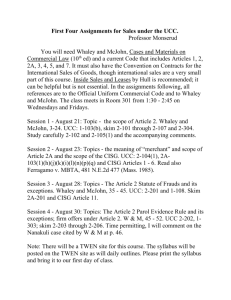

advertisement