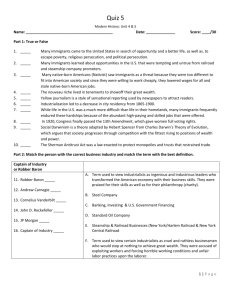

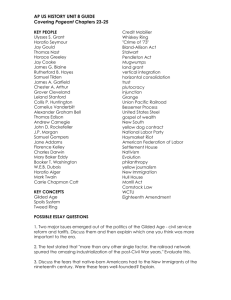

TAP 24 Rise of Industry

advertisement

TAP Chapter 24: The Rise of the Industrialists Essential Questions: How does the American Dream evolve in an era of tremendous economic stratification (think: Gilded Age mansions versus tenement housing)? Who has access to the American Dream during the Gilded Age? Is the “rags to riches” story a myth or a reality? How do industrialists justify their extreme wealth in contrast to the poverty of so many Americans during the Gilded Age? How does Social Darwinism connect to the zeitgeist of determinism? Building a Transcontinental Railroad Despite her beginnings as an agricultural nation, America emerged as an economic world power by 1900. The growth of the railroad industry led the way, with the amount of rail jumping from 35,000 miles at the end of the Civil War to almost 200,000 by 1900, largely facilitated by government loans and land grants to railroad companies (which fueled speculation). Southern secession had guaranteed that the proposed transcontinental railroad would be build through the North. Making use of Chinese labor from the West and Irish from the East, the transcontinental railroad was completed with a golden spike at Promontory Point, Utah, in 1869. By 1893, the country boasted five transcontinental railroads and stimulated urban growth outside of the East coast. Rise of the Trusts: Carnegie and Steel, Rockefeller and Oil American manufacturing improved during the Gilded Age due to greater mechanization and investment in machines. Business leaders also focused on efficiency, as Andrew Carnegie engineered vertical integration, and many business titans embraced horizontal integration, which led to monopolies and trusts that knocked most, if not all, competitors out of business. Andrew Carnegie – Carnegie Steel Company, eventually sold to JP Morgan John D. Rockefeller – Standard Oil Company, driven by the invention of the automobile Cornelius Vanderbilt – Made a fortune in the steamboat and RR industries, credited with promoting steel rail lines over iron lines and a standard gauge of track JP Morgan – Consolidated railroad companies, became the “banker’s banker” James Buchanan Duke – American Tobacco Company Meanwhile, in the South, the cotton legacy led to a growing textile manufacturing industry and the growth of Southern mill towns. Horatio Alger, Jr. and the Rags to Riches Dream Amid the economic landscape of industrialism, a new brand of popular literature emerged, the “rags to riches” tale. Horatio Alger, Jr, a writer educated at Harvard and known for writing boy’s literature, began writing dime novels featuring a male Cinderella myth: the young, clever, but impoverished boy who, by nature of good luck and cunning, rises from errand boy to respectable business magnate or politician within the urban jungle. Most famous of these was his “Ragged Dick” series. Why would the “rags to riches” genre emerge during the Gilded Age and not another point in American history? Was the narrative a myth or reality for most Americans? Industrial Justification: Social Darwinism and the Gospel of Wealth With harsh criticism likening robber barons to the lords of medieval England, industrialists were hard-pressed to justify their tactics and good fortune amid the poverty of the era. Many advocated the philosophy of Social Darwinism, a social philosophy derived from Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of the Species. Herbert Spencer and William Graham Sumner argued that the wealthy and powerful had simply won the battle of economics based on their superior natural abilities—meaning they were “fitter” than the poor and, thus, owed the poor nothing. Such attitudes fed contempt for the poor and, when taken to their extremes, formed the basis for the application of such thought to genetics and heredity that would culminate in the American Eugenics movement. I want “only the big ones, only those who have already proved they can do big business. As for the others, unfortunately they will have to die.” - John D. Rockefeller, Standard Oil Trust “The law of competition may be sometimes hard for the individual, [but] it is best for the race, because it insures the survival of the fittest in every department.” - Andrew Carnegie, Carnegie Steel Some business titans did acknowledge a responsibility that came with prosperity. Andrew Carnegie wrote the Gospel of Wealth in 1889, in which he advocated for philanthropy by the nation’s industrialists, and many industrialists gave millions to educational and cultural institutions. Reigning in the Robber Barons Although railroad tycoons pushed through efficiency and safety developments including steels lines, luxurious Pullman cars, air brakes, and standardized time, they grew infamous for manipulating stock prices to build fortunes at the expense of the public and having no concern for the law—leading the public and their critics to label them “robber barons.” The government finally stepped in with rudimentary efforts to regulate after the Supreme Court ruled in Wabash, St. Louis, and Pacific Railroad Company v. Illinois that the federal government, not the state, had the power to regulate. In 1887, Congress passed the Interstate Commerce Act, requiring railroad companies to publish their rates openly and forbidding discrimination against shipping companies but ultimately doing little to curb railroad business dealings. Congress finally attempted to reign in the trusts with the Sherman Anti-Trust Act of 1890, which aimed at curbing monopolies but actually only limited labor unions. Nonetheless, it was a step in the direction of controlling monopolistic trusts. Labor Unions The growth of industrial America would not have been possible without the sweat and toil of workers, utterly anonymized and depersonalized within the factory system. Although workers unionized, they needed corporations, while corporations could replace workers with strikebreaking “scabs,” and they often had the support of the federal government to break strikes (as demonstrated in the Great Railroad Strike of 1887). In 1866, the National Labor Union had quickly amassed 600,000 members (excluding Chinese, women, and African Americans) but had collapsed during the financial crisis of the 1870s. A new organization, the Knights of Labor, emerged in 1869 for both skilled and unskilled workers and demanded equal pay for women, and end to child labor, immigration restrictions, an eight-hour workday and a graduated income tax. The Knights of Labor gained power until the 1880s, when a number of strikes failed, and the bloody Haymarket Square riot of 1886 led the public to unfairly associate the group with anarchist groups. In 1886, Samuel Gompers created the American Federation of Labor, a federation that unified several smaller unions and campaigned not against capitalism, but simply for better rights and wages for workers and would boast strong membership (peaked at 1.4 million) throughout the turn of the century. The AFL was a federation of skilled workers only, and they fought for an eight-hour day as well as employer liability and workers’ compensation. In 1892, the Homestead Strike brought the steel industry to a halt, and in 1894, the Pullman Strike, in which workers for the Pullman Palace Car Company went on strike, paralyzed travel in the West, leading the federal government to call in troops to settle disputes, but not before industrialists hired the Pinkertons to infiltrate labor unions and ultimately battle with striking workers.