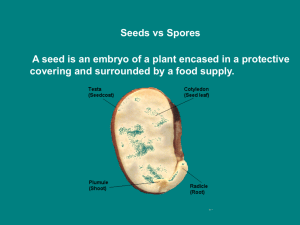

Beghini2014 - University of Edinburgh

advertisement