Social recovery in early psychology

advertisement

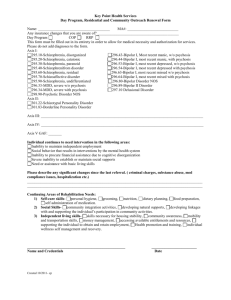

Social Recovery in Early Psychosis: Assessment and Intervention Dr Jo Hodgekins Acknowledgements Social disability as a primary target? Delayed social recovery: the clinical picture Very low levels of activity Amotivation Depression and loss of hope Drug abuse Social anxiety, withdrawal, avoidance Residual “schizotypal” symptoms: anomalous experiences, voices, paranoia (Hodgekins et al, 2012) Possible Selves Hoped for “Go back to work” “Have a girlfriend” “Be well, not be ill” “Meet Mrs Right, have a family and settle down” “Lose weight and be healthier” “Be free of anxiety, be able to manage it successfully” Feared “Not manage to do anything and end up on benefits” “Homeless and living in a night shelter” “Not get a job” “Be on medication forever” “To go into hospital again and have another breakdown” Research Questions 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. How can we assess delayed social recovery? When do social functioning difficulties occur? What is the prevalence of delayed social recovery in early psychosis services? What are the predictors of delayed social recovery? How do we intervene? Assessing functional recovery following psychosis: a problem Traditional measures focus on the deficit syndrome – Or focus specifically on work and education – Young people with first episode psychosis have different difficulties Whilst work and education are important outcomes, they aren’t the only markers of recovery “Structured activity” is broader and more inclusive Non-clinical norms Assessing social recovery using the Time Use Survey Large study of time use in UK (Office for National Statistics) Structured interview Norms provided for different age groups – Average amount of time (hrs per week) spent in different activities (work, education, hobbies, leisure, sport…) Compare time use in early psychosis to the general population Why Time Use? “Measuring time use is an important way of measuring participation in a range of activities which may have significant economic, societal, and personal benefits” (International Association for Time Use Research) Time spent in structured activity has previously been shown to be associated with increased mental wellbeing (Fletcher et al, 2003) Engaging in activity gives meaning to people’s lives Psychometrics: Validity Structured Activity Quality of Life 0.43** SOFAS 0.31** Time Budget 0.53** PANSS Positive -0.03 PANSS Negative -0.21 PANSS General -0.02 *p <0.05, **p <0.01 Hodgekins et al. (submitted to Schizophrenia Bulletin) When do social functioning difficulties occur? Compare weekly hours in structured activity across samples of individuals at different stages of psychosis with an age-matched non-clinical sample: – – – – ONS non-clinical sample (N = 6388) EDIE-II At-risk mental state (N = 288) EDEN First episode psychosis (N = 1027) ISREP Delayed social recovery (N = 77) Hodgekins et al. (submitted to Schizophrenia Bulletin) Results Hours per week in Structured Activity 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 Non-Clinical (ONS) At-risk Mental State (EDIE-II) First Episode Psychosis (EDEN) Delayed Recovery (ISREP) 30 hours per week as a cut-off Use of ROC curves to determine best cut-off to distinguish clinical and nonclinical groups Hodgekins et al. (submitted) Hodgekins et al. (submitted to Schizophrenia Research) Conclusions Individuals with psychosis spend significantly less hours per week engaged in structured activity than an age-matched non-clinical comparison group This reduction in activity begins before the onset of psychosis and is clearly present in the at-risk mental state stage Time use discriminates between clinical and non-clinical groups and can be used to assess social disability Hodgekins et al. (in prep) What is the prevalence of social disability in first episode psychosis National EDEN study Longitudinal cohort study of individuals with first-episode psychosis receiving early intervention from services across the UK between 2006-2010 (N = 1027) – Birmingham, Norwich, Cambridge, Cornwall, Lancashire Time Use assessed at baseline, 6 months and 12 months Hodgekins et al. (in prep) Hours per week in Structured Activity Whole group (N = 1027) Baseline 6 months 12 months Hodgekins et al. (in prep) Hours per week in Structured Activity Individual trajectories Baseline 6 months 12 months Hodgekins et al. (in prep) Trajectories of social recovery Recovery is heterogeneous (large SDs) Identifying a sub-group of individuals who may be at risk of poor social recovery would be useful in treatment planning Use Latent Class Growth Analysis (LGCA) to identify smaller homogeneous subgroups (aka “latent classes”) in larger sample (Jung & Wickrama, 2008) Hodgekins et al. (in prep) Subgroups Hours per week in Structured Activity 100 Low Stable 90 80 7% 70 60 27% 50 40 30 20 66% 10 0 Baseline 6 months 12 months Moderate/ Increasing High/ Decreasing Hodgekins et al. (in prep) Conclusions A large proportion of individuals remain socially disabled following 12 months of EI service provision Requires specific targeting? Hodgekins et al. (in prep) What predicts social recovery problems? Predictors of poor functional outcome: – – – – – – Male gender Younger age of onset Poor premorbid adjustment in adolescence Long DUP Ethnic minority status Baseline negative symptoms May be able to identify those at risk and intervene early? But how? The Social Recovery CBT approach (Fowler, French, Hodgekins et al, 2012) Formulates the barriers to recovery in terms of avoidance Intervenes with the system to overcome stuck social position and adverse social circumstances Fosters hope and motivation and positive sense identity and view of self and future (self as hero) Promotes specific meaningful individualised activity goals linked to case management and IPS strategies Works “in vivo” promoting change in activity Encourages behavioural tests to establish positive sense of self and personal agency while managing social anxiety and paranoia SRCBT: Specific cognitive behavioural strategies Negative symptoms: testing expectation of feelings of lack of pleasure or mastery in social situations Social anxiety/paranoia: overcoming avoidance in response to worries about social appraisals using specific targeted behavioural experiments Schizotypal symptoms: decreases catastrophising appraisals about relapse associated with minor psychotic experiences Intervention Assessment and engagement – – Lots of compassion and validation but also… Optimism for change and hope for the future Building a “self-as-hero” narrative – You got through it, survivor, hidden resilience – e.g. analogy of favourite computer game character who “keeps on going” despite adversity Building positive sense of self and self-compassion Identification of values, short and long-term goals and barriers – Miracle question (job, university) Intervention contd. Addressing ambivalence/fears about change Symptoms & beliefs about psychosis – – – Addressing avoidance – – Information about psychosis – exposure Normalising – behavioural experiments Symptom management Graded exposure re: using the bus ACT-based metaphors – you can do things AND have these experiences Behavioural activation – Increasing activity levels and experience of pleasure Intervention contd. Working towards values – – – – Career – researching different careers, link up with work-based organisations in voluntary sector who arranged a work placement Leisure – new activities might like to do Personal Growth – comfort zone vs. stretching self Friends/social life – increasing social contacts Behavioural experiments – – Making mistakes Social anxiety Improving Social Recovery in Early Psychosis: pilot study of SRCBT Mean Difference in hours per week in structured activity ISREP study results 20.00 15.00 10.00 5.00 0.00 -5.00 -10.00 control treatment Allocation Instilling hope and a positive sense of self Summary Delayed social recovery problems are common following a first episode of psychosis and require further targeted intervention A social recovery focused CBT approach looks promising in addressing these difficulties The future… Sustaining Positive Engagement and Recovery in First Episode Psychosis (SuPER EDEN study 3): An RCT of social recovery CBT in individuals with first episode psychosis (N = 75 treatment, 75 control) – Funded by NIHR Programme Grant Detection and Prevention of Long-term Social Disability amongst Young People with Emerging Mental Health Problems: an RCT of social recovery CBT (N = 50 treatment, 50 control) – Funded by NIHR HTA (Fowler, French, Hodgekins et al) Thank you for listening! j.hodgekins@uea.ac.uk