TINUADE AKOMOLAFE-WILSON Justice, Court of

advertisement

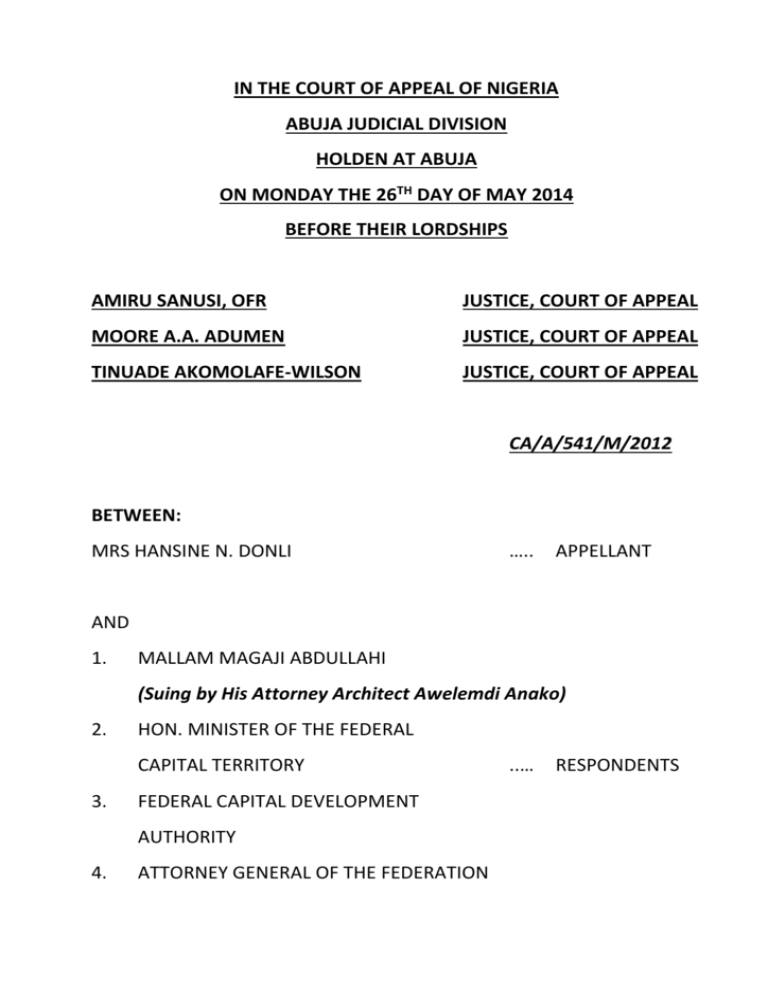

IN THE COURT OF APPEAL OF NIGERIA ABUJA JUDICIAL DIVISION HOLDEN AT ABUJA ON MONDAY THE 26TH DAY OF MAY 2014 BEFORE THEIR LORDSHIPS AMIRU SANUSI, OFR JUSTICE, COURT OF APPEAL MOORE A.A. ADUMEN JUSTICE, COURT OF APPEAL TINUADE AKOMOLAFE-WILSON JUSTICE, COURT OF APPEAL CA/A/541/M/2012 BETWEEN: MRS HANSINE N. DONLI ….. APPELLANT AND 1. MALLAM MAGAJI ABDULLAHI (Suing by His Attorney Architect Awelemdi Anako) 2. HON. MINISTER OF THE FEDERAL CAPITAL TERRITORY 3. FEDERAL CAPITAL DEVELOPMENT AUTHORITY 4. ATTORNEY GENERAL OF THE FEDERATION ..… RESPONDENTS JUDGMENT (TINUADE AKOMOLAFE-WILSON, JCA) This is an appeal against two interlocutory decisions of Honourable Justice S.C Orji of the High Court of Federal Capital Territory Abuja delivered on 10th of November, 2011 and 3rd May 2012 respectively. The 1st respondent as plaintiff claimed initially against the 1st – 3rd Defendants (now 2nd – 4th Respondents) by his amended statement of claim the following reliefs: “a. A declaration that the purported revocation of the Plaintiff’s Certificate of Occupancy number FCT/ABI/KN.1202 (new number AN 10837 over Plot 268 Jabi District Abuja by the 1st Defendant (which revocation has not been communicated to the Plaintiff) is null and void and of no effect whatsoever. b. An order restoring the Plaintiff’s Certificate of Occupancy Number FCT/ABU/KN.1202 (new number An 10837) over all that parcel of land known and called Plot 268 Jabi District Abuja. c. An order Defendants or perpetual from injunction against disturbing the Plaintiff the use, possession and quiet enjoyment of Plot 268 Jabi District Abuja and covered by Certificate of Occupancy Number FCT/ABU/KN.1302 with new number AN 10837.” On 10th of March, 2008 an order for interlocutory injunction was granted in favour of the plaintiff (1st respondent) restraining the defendants acting by themselves or their servants, agents or privies and all persons claiming through them from taking possession, development and/or exercising any right of ownership over the land in dispute pending the determination and leaving, the substantive suit. This order was pasted on the disputed land. The appellant to whom the 2nd and 3rd respondents had re-allocated the land after revoking the title of the 1st respondent, and who has been in possession since 25th March 2006, brought an application, and was subsequently joined as 4th Defendant to this action. The Appellant counter – claimed as follows:“1. A Declaration that the Revocation of the Plaintiff’s rights in the disputed land is constitutional, since the Plaintiff failed to fulfil the terms and conditions for the grant of the revoked Certificate of Occupancy. 2. A Declaration that the grant of a Certificate of Occupancy to the 4th Defendant by the 1st Defendant is Lawful, Constitutional and in accordance with the interment of the Land Use Act Plaintiff having breached the conditions for the grant. 3. An Order of perpetual injunction restraining the plaintiff and or his privies and assigns from interfering with the 4th Defendants possessory rights on the land. 4. The sum of 5 Million being general damages. 5. Costs of this action assessed as N1 Millions.” At the hearing the 1st respondent (plaintiff) testified as PW1 and called no further witness. The 2nd and 3rd respondents (1st and 2nd defendants) called DW1 and DW2 to testify. DW1, one Mohammed Umar Gari, sought to tender the revocation letter, proof of service of the notice of revocation sent to the 1st respondent by DHL courier amongst other documents. The 1st respondent’s counsel objected to the tendering of the DHL courier on the basis that the DHL delivery note was served during the pendency of the case contrary to section 91(3) of the Evidence Act, as amended. This objection was overruled by the trial judge on the basis that section 91(3) (now S.83 (3) cannot apply. However, the trial judge held that the DHL delivering note was a copy and no foundation was laid by counsel to tender a copy but he neither rejected the document not admit same. The document was thus left hanging in the air. DW2 testified as to the grounds of the revocation of the 1st respondent’s title on the ground of breach of conditions attached to the grant of the right of certificate of occupancy. The Appellant (4th Defendant) as DW3 later sought to tender her certificate of occupancy as contained in her file, dated 16th May, 2007, among other documents. The 1st Respondent’s counsel objected on the basis that it was issued by the 2nd Respondent (1st Defendant) during the pendency of the suit contrary to section 91(3) of the Evidence Act (now section 83 (3) of Evidence Act, as amended). The learned trial judge upheld the objection and rejected the Certificate of Occupancy and accordingly marked it as “rejected 2.” Being dissatisfied, the Appellant appealed against the said ruling by her notice of appeal dated and filed on 23rd of Monday 2011 (see pages 32 – 135 of the record of appeal). After the close of the case, counsel to the 2nd and 3rd Respondents (1st and 2nd Defendants), who came into the matter midstream, brought an application for leave of the trial court to amend paragraph 15 of their statement of defence dated 22nd October, 2008; re-open their case and call additional witness to tender the proof of DHL delivery note of the service of the notice of the revocation on the 1st respondent to enable court to properly admit same. All the other defendants did not oppose the application, but the plaintiff opposed it. The learned trial court refused the application on the ground that “the document was not in the contemplation of the parties when the case was filed. The Appellant, piqued by the ruling of the court, filed the Notice of Appeal on 16/5/2004 (pages 166 – 170 of the Record of Appeal). In accordance with the rules of this court, parties filed their briefs of argument. In the brief of argument settled by the learned Senior Advocate, J.D. Daudu, two issues were formulated for determination namely:“(1) Whether the learned trial Judge Hon. Orji J did not err in law when he rejected the Certificate of Occupancy issued by the Minister of the FCT to the Appellant on the ground that the said document was issued whilst the proceedings had commenced or being contemplated on account of a perceived breach of the provisions of section 83 (3) of the Evidence Act? (Grounds 1 and 2 of the Notice of Appeal dated and filed on the 23rd of November 2011) 2. Whether the learned trial Judge Hon. Orji J was not in error when he refused that 1st and 2nd defendants application to inter alia reopen their case and resubmit the proof of service by DHL of the notice of revocation, which in an earlier ruling was not admitted in evidence by the Court? [Grounds 1, 2 and 3 of the Notice of Appeal dated and filed on the 16th of May 2012] Mrs. Uju Onukwuli of learned counsel for the 1st respondent and Mrs. Rita Chris Garuba, of learned counsel for the 4th respondent in their respective briefs of argument adopted the issues as couched by the appellant. Mr. David Mando filed the brief of argument for the 2nd and 3rd respondents jointly. The issues distilled for determination by him are also similar with those formulated by the appellant. It is therefore not necessary to reproduce them. Suffices to say that his issue 2 is a reply to appellants Issue no 1, while his issue No.1 is the appellant’s issue no. 2. I hereby adopt the issues as drafted by the appellant for determination of this appeal. On the 26th of February, 2014, the learned counsel for the appellant filed appellants reply brief to 1st respondents brief of arguments. It is important to note immediately that all the respondents apart from the 1st respondent support the appeal and urge us to allow the appeal. ISSUE ONE: “(i) Whether the learned trial Judge Hon. SC Oriji J did not err in law when he rejected the Certificate of Occupancy issued by the Minister of the FCT to the Appellant on the ground that the said document was issued whilst the proceedings had commenced or being contemplated on account of a perceived breach of the provisions of section 83-(3) of the Evidence Act? (Grounds 1 and 2 of the Notice of Appeal dated and filed on the 23rd of November 2011) It was submitted for the appellant that the minister for the FCT (2nd respondent) who issued the rejected Certificate of Occupancy is not a “person interested” under the provisions of the law because the document was made in his official capacity and he is not a person personally interested in the outcome of litigation, or has any pecuniary interest in the matter. Learned Senior Advocate cited in support two relevant decisions: N.S.I.T.F.M.B. V. Klifco Nig. Ltd. (2013) 13 NWLR (Pt. 1211) 30 at 327-328 and Abdullahi v. Matsidom & Ors (2011) 3 NWLR (Pt. 1233) 55 at 71 – 72. He urged the court to resolve this issue in favour of the appellant. As said earlier, the 2nd and 3rd respondents and the 4th respondents aligned themselves with the arguments of the appellant with the additional authority of High-grade Maritime Service Ltd v. FBN Ltd (1991) 22 NSCC (Pt 1) 119 at 135 supplied by Mr. Mando while Mrs. Chris-Garuba added the following cases in support of the same principle of law namely: (1) Nigeria Social Insurance Trust Fund Management Board v. Klifco Nigeria Ltd (2010) NWLR (Pt. 1211) at 313 (2) H.M. S. Ltd v. First Bank (1991) 1 NWLR (Pt. 167) 290 (3) Chief Christopher I. Monkom & 2 Others v. Augustine Odili (2009) 11 NWLR 2213 at 232 para 68-69. I do not therefore find it expedient to reproduce their submissions as it will merely amount to repetition. Mrs. Onukwuli, of learned counsel for the 1st respondent on his part also relied on the two cases cited by the appellant but distinguished them. She contended that where the official, like the 2 nd respondent is discharging a ministerial duty which involves a personal opinion the document issued while proceedings are pending will be inadmissible. She argued that the 2nd respondent is not under a statutory duty to grant a right of Certificate Occupancy to all persons. Reference was made to the provisions of sections 5(1)(a) and section 9(i) (a) of the Land Use Act LFN, 2004 which provide as follows:“Section 5(1)(a) It shall be lawful for the Governor in respect of land, whether or not in an urban area to – (a) Grant statutory right of occupancy to any person for all purposes; Section 9(1)(a) It shall be lawful for the Governor - (b) When granting a statutory right of occupancy to any person;” She also referred to the definition of the word “any” by the Oxford Advanced Learners Dictionary (6th Edition) at page 42 as: “One or more of a number of people or things especially when it does not matter which.” According to her, since the law prescribes that the certificate could be granted to any person, the act of granting a certificate of occupancy therefore involves a “personal opinion,” thereby excluding the certificate of occupancy from those documents admissible under section 83(3) of the Evidence Act. Expectedly, she urged the court to uphold the learned trial’s decision on this issue in favour of the 1st Respondent. On the 26th of February 2014, the learned Senior Advocate promptly filed the Appellant’s reply brief in response to the 1 st respondent brief of argument. On issue one, Mr. Daudu noted that the 1 st respondent’s submission is tenous in the extreme in that there is no evidence supplied by the respondent that the minister was acting in a personal capacity or rendering a private opinion at the time he issued the certificate of occupancy. He urged us to resolve issue No.1 in favour of the appellant. Section 83(3) of the Evidence Act 2011, as amended which is in pari material with section 93(3) of the repealed Evidence Act Cap 112 LFN 2004 deals with documents issued pendent lite. It provides as follows:- “(3) Nothing in this section shall render admissible as evidence any statement made by a person interested at a time when proceedings were pending or anticipated involving a dispute as to any fact which the statement might tend to establish.” The general rule is that a document made by a party to litigation or otherwise a person interested when proceedings are pending or is anticipated is not admissible. Therefore before a statement can be admitted under Section 83 of the Evidence Act, it must not have been made “a person interested” nor “when proceedings were pending or anticipated.” The provision of this subsection can be examined in two perspectives namely (i) “a person interested” and (ii) “when proceedings were pending or anticipated.” In this appeal, it is common ground that at the time of making the Certificate of Occupancy in question, the proceedings at the lower court had commenced. The vexed issue is that it was made by a “person interested” when proceedings were already pending. What is being disputed is the connotation of the phrase “interested party” in the circumstances of this case. The meaning of this phrase under the purview of section 83(3) of the Evidence Act (formally, S.90(3), S.91(3), and later 93(3) of the Evidence Act) has been subject of judicial pronouncements in several cases in Nigeria. In Nicholas Ogidi & Ors v. Chief Daniel Igba & Ors (1999) 10 NWLR (Pt.621) 42 at 69 it was status thus:“It is against the provisions of Section 90(3) now 91(3) of the Evidence Act to admit in evidence a document made by an interested party to a suit during the pendency of the suit.” A person interested within the meaning of subsection (3) is one who will derive an advantage or benefit from the proceedings which are either pending or anticipated. Conversely, a person not interested and therefore does not come under this provision is a “person who has no temptation to depart from the truth on one side or the other, a person not swayed by personal interest, impartial, independent.” The disqualifying interest is a “personal interest.” Any interest in an official capacity does not come under this qualification as an official is deemed to be carrying out his duties in the ordinary course of official business. In other words, an official ordinarily is presumed to carry out his duties simply in a completely “official” capacity as opposed to “personal” capacity unless proved otherwise. In law there is a presumption of regularity in certain facts. By the provisions of section 167(C) of the Evidence Act 2011 (as amended) section 149(c) of the repealed Evidence Act, “167. The court may presume the existence of any fact which it deems likely to have happened, regard shall be had to the common course of natural events, human conduct and public and private business, in their relationship to the facts of the particular case, and in particular the court may presume that(c) The common course of business has been followed in particular cases.” In my view, in the light of the Section 167(C) of the Evidence Act, it is presumed that an official such as the Minister of the Federal Capital Territory carries out his duties in the common course of the operation of such duties. The cited recent decision of the Supreme Court in N.S.I.T.F.M.B v. Klifco Nig. Ltd. (supra) on which the court relied on its earlier decision in High-grade Maritime Services Ltd. v. FBN Ltd (1991) 1 NWLR (Pt. 167) 290 at 372-313 is very illuminating. I also quote it in extensor for purposes of clarification – “It seems to me the provision excludes documents made in anticipation of litigation by a “person not personally interested” in the results of the Litigations. Thus the general principle is; that the document made by a party to a litigation or person otherwise interested when proceedings are pending or is anticipated is not admissible… The disqualifying interest is a personal not merely interest in an official capacity … Where however the interest of the maker is purely official or as a servant without a direct interest of a personal nature, there are decided cases that the document is not thereby excluded… The nature of the disqualifying interest will depend upon the nature of duty undertaken by the servant. Where from the nature of the duty he can be relied upon to speak the truth and that he will not be adversely affected thereby, the document has always been admitted in evidence. This is because the rationale of the provision is that he must be “a person who has no temptation to depart from the truth on one side or the other – a person not swayed by personal interest, but completely detached judicial, impartial, independent” there must exist a real likelihood of bias. Hence where an official is discharging a ministerial duty, which does not involve any personal opinion, the question of bias will not be in issue. Such document will be admissible under Section 90(3) of the Evidence Act. The facts in this case have not disclosed that any of the litigation. The Court below was therefore right to result of the litigation. The Court below was therefore right to have admitted and acted on Exhibits 13 and14.” See High Grade Maritime Services Ltd v. FBN Ltd (supra); Nigeria Social Insurance Trust Fund Management Board v. Klifco Nig. Ltd. (supra); Christopher I. Mankom & 2 ors v. Augustine (supra). In Abdullahi v. Maitsidau & Ors (supra), this court, per Okoro, JCA, as he then was, expatiated thus – “On the submission that Exhibit D, E or F offends section 91(3) of the Evidence Act, I hold the view that a document made by the Electoral body in compliance with statutory mandate and not by a person personally interested in the outcome of litigation cannot be said to have been made by a person interested. In Alhaji Musa Ya’u v. Maclean D.M. Dikwa (2001) 8 NWLR (Pt.714) 127, this court held that in order to ascertain or determine, whether the maker of a document sought to be tendered is a person interested in the litigation under section 91(3) of the Evidence Act, the circumstance surrounding the making of the document and whether the maker can be said to have an interest of a personal nature, must be examined and ascertained. A person who is not personally interested in the result of litigation cannot be described as one “interested” in the proceedings. A person under official assignment or statutory duties and who has no personal benefit from the outcome of the litigation cannot be said to be a person interested under section 91(3) of the Evidence Act. See also Apena v. Aiyetobi (1989) 1 NWLR (pt. 95), H.M.S. Ltd. v FBN Ltd (1991) 1 NWLR (Pt.167) 290, Anyaebosi v R.T. Briscoe Nig. Ltd (1997) 3 NWLR (Pt.59) 84. As I said earlier, the Publication of names of cleared candidates by the Kano State Electoral Commission in Exhibits D, E or F pursuant to statutory function cannot be said to have offended Section 91(3) of the Evidence Act, after all, the Appellant did not show the interest of the 3rd Respondent in the matter. It is not enough for a person to allege that a party is interested in the litigation; he must lead evidence to establish that interest. It should not be left to conjecture.” The submission of the 1st Respondent that because the provisions of Section 5(1)(a) and Section 9(1) (a) of the Land Use Act refers to “any person” makes the issuance of a Certificate of Occupancy a personal opinion of the Minister suggesting that the question of bias may be an issue is to me a very puerile argument. In the first place, the definition given to “any” by learned counsel is restrictive, as the word has a diversity of meaning and may be employed to indicate “all” or “every” as well as “some” or “one”; - See Blacks Law Dictionary 6th Edition at p.94. More important however is the fact that before a person making a statement or document can be and to be a “person interested”, there must be a likelihood of bias. The authority cited by counsel ostensibly in support of his argument is adverse to his submission. In the decision of N.S.I.T.F.M.B v Klifco Nig. Ltd (supra) the court at pages 327 and 328 stated as follows – “Of course, before there will exist a disqualifying interest, or a person will be regarded as “a person interested” there must exist a real likelihood of bias. Hence where an official is discharging a ministerial duty, which does not involve any personal opinion, the question of bias will not be in issue. Such document will be admissible under s.90(3) of the Evidence Act.” The attempt to distinguish Klifco Nig. Ltd case is of no value to support the decision of the learned trial Judge. There has to be evidence that the Minister was acting in his personal capacity or rendering a private opinion at the time he issued the Certificate of Occupancy. I am in agreement with the learned Senior Counsel for the Appellant that in the absence of any such evidence of special interest in the Minister, it cannot be assumed that he has special interest in the matter. I am of the view that the 2nd Respondent, the Minister of Federal Capital Territory issued the Certificate of Occupancy purely in his official capacity under the mandate of a stature. He has no personal or financial interest to be derived from his action, as no such evidence was so established. In the circumstances of this case, the rejection of the Certificate of Occupancy of the Appellant made by the Minister of Federal Capital Territory in his official capacity and in the ordinary course of his official business, by a person who has no pecuniary or personal interest in the subject matter of litigation is wrong. The document is therefore admissible as the Minister (2nd Respondent) is not interested party within the meaning and contemplation of Section 83(3) of the Evidence Act, 2011 (as amended). Issue one is hereby resolved in favour of the Appellant. Issue Two Whether the learned trial Judge Hon. Oriji J was not in error when he refused the 1st and 2nd defendants application to inter alia reopen their case and resubmit the proof of service by DHL of the notice of revocation, which in an earlier ruling was not admitted in evidence by the Court? [Grounds 1, 2 and 3 of the Notice of Appeal dated and filed on the 16th of May 2012]” It was submitted for the Appellant that the amendment sought by the 2nd and 3rd Respondents was necessary for the just determination of this case. He explained that it was meant to retender the proof of service of the revocation letter from DHL served on the 1st Respondent which is a material issue for the determination of this case. Learned Senior Counsel recalled that the said document at the initial attempt to tender it, was neither admitted nor rejected by the learned trial Judge, rather it was left in limbo; even though the document ought to have been admitted since it is pleased and it is relevant. The reason for refusal of amendment of pleadings by the learned trial Judge so as to retender the document, he argued amounts to overruling himself in view of the fact that he had earlier held that S. 91(3) of the Evidence Act was inapplicable. The excuse for the rejection on the basis that the document is a photocopy, he argued rising on issue suo motu without calling for the input of counsel. Relying on Ekpenyong v Nyong (1975) 2 SC 71, Mr Dodo submitted that the court descended into the arena. Learned Senior Counsel freely submitted that by blocking the admissibility of the document, the trial court showed bias against the Appellant, as a party ought to be afforded opportunity to put his case properly before the court – Celtel Nig Ltd v Econet Wireless Ltd (2011) 3 NWLR (Pt.1233) 156 at 169. The 2nd and 3rd Respondents also in criticism of the refusal of amendment of their pleadings and rejection of the DHL delivery note re-stated in addition to Appellant’s submission the principles governing the amendment of pleadings. He emphasized that amendment can be made at any time before judgment except if the amendment sought will change the cause of action or will introduce a new case. He relied on Akinwuowo v Fafimoju (1965) NMLR 349 at 351; Cropper v Smith (1884) 26 Ch.D. 700 at 711. On her part, Enewa Rita Chris Garuba (Mrs) also lucidly explained the reasons for the necessity of the amendment which is relevant to the Appellant’s case as it the DHL is the proof of delivery of the Revocation Letter to the 1st Respondent. She opined that the learned trial Judge refrained from making the document “rejected” since it is though a copy, is ordinarily admissible on fulfilment of certain conditions, that is by laying an evidentiary foundation for its admission – Yero v UBN Ltd (2000) 8 NWLR (Pt.657) 470. As for the 1st Respondent, he completely refrained to answer the points raised by the Appellant on this issue. Instead, he raised what is semblance to a preliminary objection. He submitted that the issue formulated herein is in respect of the refusal of an application made by the 2nd and 3rd Respondents from re-opening their case by an application for amendment and not based on any application by the Appellant. He compared the situation of the Appellant to that of a party appealing on an issue by another party who is not an Appellant in the case. Relying on Egbarin Jnr v Aghoghobia (2006) 16 NWLR (Pt. 846) 380 at 390, he submitted that an Appellant who did not seek to assert a right at the lower court has no right of appeal for the court to pronounce on such reliefs. It is trite law that a Respondent’s brief of argument is meant to address the issues raised by the Appellant. Where the Respondent fails to address the issues raised by the Appellant, he is deemed to admit the issues so raised by the Appellant. – Eigbe v N.U.T (2008) 5 NWLR (Pt.1081) 604 at 625 paras.G-H. The 1st Respondent from his brief clearly has no answer to the issues on the merits as raised by the Appellant. In my view, he is deemed to have admitted same. Besides, I am at one with the observation of Mr. Daudu that this objection ought to be disregarded having flouted the Rules of Court. By Order 10 Rules 1-3, a Respondent intending to rely upon a preliminary objection must file an appropriate Notice of Preliminary Objection and shall give notice of same to the Appellant three days before the hearing of the appeal. See Ephraim v Afribank (Nig) PLC (2009) 10 NWLR (Pt.1150) page 543 at 550 paras. E-H. However, permit me to comment that the Appellant, in the circumstances of this case is an interested party, being a party to the main case and unlike the quoted Egbarin’s case, she is a party to this appeal. See the cited case of Mobil Producing Nig. Unltd (2004) All F.N.L.R (Pt.195) 649. It is instructive to note at this juncture that the ruling in pragmatic terms is actually against the Appellant. The Appellant is the allottee to whom the Certificate of Occupancy in respect of the property in dispute was allocated after it was revoked from the 1st Respondent. The document sought to be tendered is the DHL note of delivery of the notice of revocation by the 2nd and 3rd Respondents to the 1st Respondent. The substantive ruling on this issue is on the amendment sought by the 2nd and 3rd Respondents. It is an elementary principle of law that an amendment can be made at any stage of proceedings even on appeal, so as to bring the real issue in controversy before the court for its proper adjudication. – Bank of Baroda v Iyababani (2002) 13 NWLR (Pt.785) 55 at 593; Order 4 Rule 2011; Igwe & Ors v. Kalu (2002) 2 SC (Pt.1) 94 at 114. Now, the sole aim of the amendment sought by the 2nd and 3rd Respondents is the lower court was to properly tender the delivery note by DHL of the proof of service of the revocation of the allocation of the disputed land of the 1st Respondent. At the initial stage when DW1 attempted to tender the DHL courier delivery note as proof of service of the notice of revocation of the land, the Plaintiff/1st Respondent’s counsel objected on the ground that the delivery not was served during the pendency of the case contrary to Section 91(3) of the Evidence Act (as amended). This objection was overruled by the learned trial Judge where he stated thus – “To this extent, section 91(3) of the Evidence Act is inapplicable. However, the copy sought to be tendered is a photocopy and the DW1 did not lay foundation for the admissibility of the secondary evidence at copy” (Pages 99-100 of the Record). Apparently, the learned trial Judge suspended the admissibility of this document since he neither admitted it, nor marked it “rejected”. It was in fact curiously in limbo. However, when a new counsel for the 2nd and 3rd Respondents came later into the proceedings and realised the lacuna in the 2nd and 3rd Respondent’s case with all important document of proof of delivery of the notice of revocation was still “hanging in the air”, he sought for an adjournment. The ruling of the lower court on this point is at page 126 where the learned trial Judge, in refusing the application found thus: “… It is whether the document sought to be tendered by the amendment of is necessary for the determination of this case, it is note worthy that DHL delivery note dated 15/5/2007, posted-dated the filing of this suit on 31/1/2007. The document was not in the contemplation of the parties at the time that suit was filed. In other words the document was not in existence with the Plaintiff filed this action. This means that by the proposed amendment the 1st and 2nd Defendants seek to introduce a document that was not in the contemplation of the parties when the suit was filed. After the close of trial, amendment of pleadings is not readily allowed where it is intended to raise or introduce an issue which was not in the contemplation of the parties at the time the suit was filed. From all I have said so far as the amendment sought will lead to calling of fresh evidence at this stage, the grant of that application cannot be allowed or justified.” The purport of this refusal is that its admission is caught by S.91(3) of the Evidence Act. The trial court, as indicated had initially rejected this objection. His upholding of the same objection therefore, clearly amounts to overruling himself, at the time he was functus officio. The reason for refusal of amendment on this ground is erroneous. The learned trial Judge had no power to overrule himself in the circumstances. Furthermore, the reason for initially refusing to admit the document is not tenable, as it was raised suo motu by the trial court without an opportunity of the parties to address the court. This was prejudicial to the defendant’s case in the lower court. The Appellant is the 4th Defendant in the case and the principal defendant since it is the property allocated to her that is being challenged. The rejection of this document suo motu, in the first instance on the basis of its being a photocopy is faulty. Three main criteria govern the admissibility of a document in evidence, namely (1) Is the document pleaded? (2) Is it relevant? (3) Is it admissible in law? Relevance is the hall mark of admissibility of documents. Once it is relevant and pleaded and ordinarily admissible under the Evidence Act, the such a document ought to be admitted. The issue of photocopy or custody would be immaterial. It will only go to the probative value to be attached to such documents. See Dada v Ayeni (1978) NSCC 147 at 159; Dr. Torti v Ukpabi & Ors (1984) 1 SCNLR page 214 at 227. The DHL proof of delivery of the Revocation Letter is obviously relevant to the case of the Appellant, the new allottee of the property in dispute. The document was pleaded, and evidence of it had in fact been given in the proceedings by DW1. It is ordinarily admissible in law. As rightly submitted by Mrs. Chris-Garuba, the document is admissible if the original copy is tendered or a photocopy if proper evidential foundation is laid to explain the absence of its original. See Yero v UBN Ltd (2000) 5 NWLR (Pt.657) 470 (Ratio 4) at pages 482-483 paras. H-A. I agree as submitted that his document is the live wire of the Appellant’s case, vis-à-vis her counter-claim. Since the document is ordinarily admissible, by laying the proper foundation for the admissibility of its copy, the learned trial Judge ought not to have foreclosed the defendants (Appellant inclusive) by his refusal to allow the application for amendment. In my view therefore, to reject such an invaluable relevant document, upon which a party’s case is predicated, that is before the time to evaluate the evidence to be tendered is to defeat the party’s case before it is heard. This is tantamount to driving a party from the seat of justice. See Obembe v Ekele (2001) 8 WRN page 68 at 79 para 5. The learned trial Judge was in error to have refused the amendment sought so as to facilitate the re-introduction of relevant delivery note which was otherwise admissible ab initio and is in fact still hanging in the air. Issue 2 is also hereby resolved in favour of the Appellant. Having resolved the two issues for determination in favour of the Appellant, this appeal succeeds and it is hereby allowed. In the circumstances of the success of this appeal, I hereby make the following orders:1. The Ruling of the High Court of Federal Capital Territory delivered by Hon. Justice S.C. Oriji on 10th November, 2011 is hereby set aside. 2. The Certificate of Occupancy dated 16/5/2007 and the attached site plan rejected as “Rejected 2” is hereby admitted to be appropriately marked by the trial court. 3. The Ruling of the court delivered on 3rd May 2012 by Hon. Justice S.C. Oriji is hereby set aside. The amendment of the pleadings sought by the 1st and 2nd Defendants (2nd and 3rd Respondents) is granted as prayed. 4. The case is to be remitted to the presiding judge for continuation if he still in the service otherwise the matter be re-assigned by the Hon. Chief Judge of the High Court of Federal Capital Territory for hearing de novo. Parties are to bear their costs. TINUADE AKOMOLAFE-WILSON Justice, Court of Appeal. APPEARANCE J.B. Daudu (SAN), with him Mrs H.M. Usman and Miss Raheemah Abdullahi for the Appellant and Miss Chinnelo Ogbozoi Mrs Uju Onukwuli, with her Miss E.C. Akpan for 1st Respondent. Kyonne Mando Esq. for 2nd and 3rd Respondents. Mrs Rita Chris-Garuba for 3rd Respondent with her Abraham Omah Esq. and Mathias Adeyi Esq. CA/A/541/M/2013 JUDGMENT (HON. JUSTICE AMIRU SANUSI, OFR, JCA) I had a preview of the judgment just rendered by my learned brother, T. Akomolafe-Wilson, JCA just delivered. I an in entire agreement with the reasoning and conclusion arrived at by my learned brother who also had duly considered the salient issues raised and canvassed to the parties. I also adjudge the appeal meritorious and accordingly allow same. I abide by the consequential orders made in the lead judgment. AMIRU SANUSI, OFR JUSTICE, COURT OF APPEAL CA/A/541/M/2012 JUDGMENT (MOORE A.A. ADUMEN, JCA) I read the draft of the judgment of my learned brother, Tinuade Akomolafe-Wilson JCA. I agree with my learned brother that the amendment sought by the appellant ought, in the interest of justice, to have been granted. For the reasons given by my learned brother, I also allow this appeal and abide by the orders made in the leading judgment, including the order as to costs. MOORE A. A. ADUMEIN JUSTICE, COURT OF APPEAL