Introduction During the 1980's, Thailand experienced the

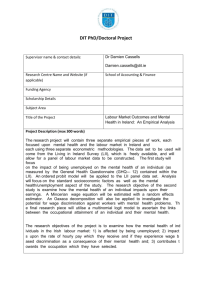

advertisement

1. Introduction During the 1980’s, Thailand experienced the phenomenal growth rate of GDP, remaining on average at 10 per cent. Since 1987 and 1990, Thailand’s economy was considered as one of the most rapid growth in the world. A number of poor was considerably reduced by five times between 1960 and 1996. However, such a development model leads to increasing income inequality that could be harmful to long term economic growth and social stability. A number of literature have been addressed this crucial issue by searching for sources of persistence of inequality1. Sine the economic crisis in 1997, the negative impact on urban labour market has been dramatic by earnings reduction and unemployment, causing increasing inequality and poverty in whole country. Specifically in term of earnings distribution, one of the main factors of those phenomena is associated with the fact that a great part of Thai population are still remaining poorly educated, particularly related to low pay in labor market. This implies directly education concerns that involve in promotion of human capital policies2. At the same time, it has been a recent debate about labour market duality, especially regarding to increase in informal economy in Thailand. In fact, informal sector has been seen for a long time as generator of poverty and inequality. Therefore, not only the importance of human capital factors should be taken into account by labour policies decisions but the role of labour market segmentation must also be considered as one of the main explanations of poverty and increasing inequality in Thailand. According to recent researches3, individual’s choices of informal sector are in great part voluntary and employments in this sector often correspond to good pay and better conditions in workplace. Empirical study applied to Mexico’s labour market by Maloney (1999) suggests that both earnings differentials and patterns of mobility indicate that much of the informal sector is a desirable destination and that the distinct modalities of work are relatively well integrated. …It is possible that the market is dualistic; however, the good job/bad job division cuts across lines of formality. [Maloney (1999) pp. 296-297]. By the same idea, my analysis tends to verify the duality of urban labour market in Thailand within formal sector. In other words, I show that even workers belonging to traditionally strong group- male head of household in the central age-group- may be confined to secondary segment. The theoretical controversy about poverty and inequality is based on relationship between productivity and earnings. Human capital theory pretend to emphasis personal attributes as the main factors in labour income. Consequently, low-wage workers are always considered as those whose skill remains relatively low. Thus, labour policies consist in increasing the skill level of low-wage workers by all programs of education and training incentives. Contrary to this theory, advocates of the duality of 1 See, for example, Isra (2001), Krongkeaw and Kakwani (2003). See World Bank (2001). 3 See Manoley (1999), Pratap and Quintin (2003). 2 labour market stipulate that productivity is now based on characteristics of jobs, not of workers. In this view, labour market is divided into two distinct segments. One, called primary sector, contains all good jobs associated with well pay, more jobs security and good conditions of workplace. The lower tier, noted secondary sector, encompass low-wage jobs, low employment security and bad conditions at work. This distinction leads to the fact that individuals with identical endowment of human capital could gain differently, depending on which sector individuals are confined in. It can be restated that the discrepancy in term of rates of returns to human capital between each sectors is due to different mechanism of earnings determination. [Leontaridi (1998) pp. 69]. Thus, empirical test for this hypothesis might show that labour market is more characterized by two wage equations than single one. Based on the Switching model with unknown regime, developed by Dickens and Lang (1985a, 1985b, 1987, 1988, 1992), the test confirm the existence of the duality of urban labour market in Thailand. The paper is organized as follow. Section 2 provides theoretical backgrounds with respect to human capital and dual labour market model. Reviews of literature will also be integrated in this section. Section 3 consists at first glance in presenting the data used, namely the Labor Force Survey collected by The National Statistics Office. Moreover, once the model specification is considered, the results of test will clarify our hypothesis of dual labour market. Section 4 describes the distribution over personal characteristics, industries and jobs categories of secondary and primary segments. 2. Human capital model and dual labour market theory 2.1. Theoretical background During the 1960’s and 1970’s, human capital approach developed by Schultz (1971) and Becker (1964) was known as the core neoclassical theory. According to this model, all human activities have a more or less positive impact on further returns. For instance, investment in schooling is a result of individual decision in order to notice more expected labour income in the future. The relationship between costs related to investment in schooling or post-schooling and returns to those investments has been presented by earnings function, pioneered by Mincer (1974). In fact, in competitive labour market, highly educated workers gain relatively more than those with poor education due to the differential in accumulated human capital investment. Otherwise, earnings inequality seems to be caused by different endowment in human capital. Conversely, according to institutional theory, there are two type of labour market, namely competing group and non-competing group market. The first one is similar to the sort of labour market described by neoclassical theory and the second one refers to groups of individuals who stay imperfectly competitive regarding to wage and employment. Beyond this concept, Doernger and Piore (1971) succeed in defining the internal et external labour market based at first on industrials relations. «…an administrative unit, …, within which the pricing and allocation of labour is governed by a set of administrative rules and procedures. The internal labour market governed by administrative rules, is to be distinguished from the external labour market of conventional economic theory where pricing, allocating and training decisions are controlled directly by economic variables. These two markets are interconnected however and movement between them occurs at certain job classifications which constitute ports of entry and exit to and from the internal market. » [Doeringer and Piore (1971) pp.2]4. Following this definition, one can divide labour market by the notion of good and bad jobs. Primary sector contains a set of good jobs. Since institutional law and costumes substitute all mechanism of labour market, employment reallocation and wage determination have been taken place through collective bargaining. Thus, wage level remains relatively high. Contrary to internal market, secondary segment consists of bad jobs with low wage. This is because of wage competition in this segment. As a result, not only wage level is rather low in this sector but its return to human capital remains also relatively small as compared to those in primary sector. Such a situation is especially due to the existence of barriers to entry to the primary segment that prevents workers from equalizing wages. In this case, since poorly workers are confined in primary sector, all proposes of given policies of reducing poverty should allow them to easily reach primary sector [Piore (1970) pp.55]5. All in all, in order to cope with the validity of the duality of labour market, one should show whether there are, on one hand, two mechanism of wage determination rather than one, and on the other hand, the existence of barriers to entry to primary sector. Such an approach requires methodological techniques so as to achieve a decisive conclusion. 2.2 Methodological approaches of dual labour market During the past three decades, there are a number of empirical literatures on tests for labour market segmented on the basis of a priori definitions of segments. At first glance, I include in a priori definitions of labour segments the techniques of classification by industrial and jobs categories. Moreover, both techniques of cluster and factor analysis will be considered as methods escaping from presupposed definition of segments. I’ll make brief descriptions of both two techniques and their corresponding methodological criticisms. Regarding to the techniques of a priori definition, the first step of process consists in dividing the labour market into two distinct segments by industrial or jobs criterions6. Then, one should estimate the earnings functions for each segment as so to verify whether two wage equations fix better data than 4 5 See Leontaridi (1998) pp.70. For instance, to gain information on employment as well as social network enables workers to escape the situation of confinement in secondary sector. [Wial (1991) pp.414.]. 6 For instance, studies of Psacharopoulos(1978), Mcnabb and Psacharopoulos(1981) were based on occupational rating scale, developed by Goldthope and Hope (1974). single one. Most of tests for the validity of dual labour market 7 confirm the bimodal wage distribution. Although several empirical studies have given almost similar conclusion, such methods suffered from technical problems related to truncation and selection bias. In fact, using a priori definition of segments –industrial and job categories- must be exposed both to truncation bias, noted by Cain (1976), and selection bias, commented by Heckman (1979). With respect to the first issue, econometric estimate on data truncated by dependent variables values entails directly biased coefficients of independent variables. This is due to the fact that some group of the population being at the top or at the bottom of wage distribution was excluded from estimations process [Cain (1976) pp.1246]. As the result, the validity of the labour market duality was provoked simply by the high degree of dependence between wage and education level. Besides allowing for this mythological limit, estimates of wage equation could be also caused by the selection bias. According to Heckman (1979), such a problem occurs by the fact that sample considered is arbitrarily selected in order to establish economic comprehension with regard to human behaviors. There are two sources of selectivity. On one hand, it concerns a process of taking a cross-section of representative samples itself. For instance, there would be an overrepresentation of women and poorly educated workers in informal sectors survey. On the other hand, the selection bias could be related to auto-selection mechanism belonging to researcher or pollster’s decision with respect to collected data. For example, self-selection of some low-wage jobs categories generates an overrepresentation of young workers with low education attainment. Consequently, the a priori classification in order to testing for dual labour market get immediately involved in this second nature of self-selection since individuals choice intervenes in models. Concerning the cluster and factor analysis, their technical advantage allows to avoid the above issues. It means that one could estimate earnings functions irrespective to a priori demarcation of labour segments. However, most of studies using cluster analysis8 seem to be divergent in their conclusions regarding to theoretical predictions of dual labour market. For instance, Anderson et al. (1986) found that their second cluster, considered as primary segment, contains not only a great proportion of workers, but also a substantial number of temporary workers, differencing from the view of dual labour market theory. Although the cluster method doesn’t suffer from truncation and self-section problems, it depends largely on both numbers of introduced variables and type of algorism used [Leontaridi (1998) pp.61]. With regard to factor analysis technique, most of empirical researches9 fell to reject the duality of labour market in favor of theory of segmentation. However, factor analysis, considered as a statistical tool used for reinforcing the homogeneity in labour market, can not explicitly explain functioning of each segments structure in term of labour income, jobs insecurity and 7 See, for example, Boston(1990), Leontarifi(1998) and Theodossiou(1995). See Anderson et al. (1986) and Sloane et al. (1993). 9 Buchele (1983) and Mcnabb (1986) used the factor analysis as so to seperate labour segments and then they proceeded the estimation of wage functions. Those studies confirmed the existence of dual labour market. 8 alike. [Thomson (2002) pp.19]10. As a result, all above methods have been strongly criticized with regard to both technical limits and economic interpretations. However, the contribution of Dickens and Lang (1985a, 1985b, 1987, 1988, 1992) beyond the switching model with unknown regime manages to get through all above criticisms. My further analysis requires the application of this model in which the structure of bimodal wage distribution might clarify better Thai labor market than would be explained by human capital model. But the question arise concerns the specification of labour markets in developing countries which might be different from those in industries countries, in particular with respect to demarcation of labour market segmentation. As noted above, most of recent literatures tend to suggest in other ways that separation of labour market segmentation cut across the lines of formality to the detriment of formal-informal distinction11. Using the switching model with unknown regime, Baash and Paresdes-Molina (1995) argued that Chili labour market was segmented during two decades. In similar conclusion12, analysis by Lachaud (1994) based on jobs and workers characteristics, namely protection, regularity and autonomy, suggest the fact that most of urban labour markets in Africa are closely related to labour segmentation caused particularly by some discrimination in workplace. In the case of Asian countries, empirical results by Bowles and Dong (2002) show that China labour market is fragmented according to types of enterprises. Moreover, foreign enterprises in China tend to pay more to senior workers than others. In Vietnam, it has been shown that labour market functioning corresponded to multidimensional approach of labour market segmentation since there were differentials in rates of returns. ADB (2005) argued that returns to human capital differed across areas (urban/rural), types of labour (formal/informal) and type of migration (migrants/non-migrants). However, policies recommendations rely on human capital promotions. In Thailand, Suehiro and Wailerdsak (2004) claims that there are internal labour market within the great enterprise, such as public company “Siam Ciment Public Company Limited”. This firm, one of the most modern companies, promotes manager carriers development and internal mobility that generate internal labour market. Therefore, this study attempts to see if among classical working-age people, there are different mechanisms of earnings determination, consequence of increasing inequality and poverty. 3. Model specification and sample selection This section consists in specifying used econometric model and referred labour data. In fact, as mentioned above, the test for the duality of labour market will be conducted under the switching model with unknown regime, pioneered by Dickens and Lang (1985a, 1985b, 1987, 1988, and 1992). 3.1 General setting 10 See also Buchele (1984). See for example, Maloney (1999), Pratap and Quintin (2003). 12 See also Heckman and Hotz(1986) for Panama. 11 The switching model is considered as one of the endogenous econometric model13 since individual’s classification into primary and secondary segments is basically conditioned by observed variables, particularly appeared in data. To begin, consider a worker who maximizes the lifetime utility functions over wage and nonpecuniary characteristics of the job. The standard form of switching model with one sorting equation and two regimes equations could be described as follow: ln Wip X i p pi (1-1) ln Wis X i s si (1-2) Z *i Di wi (1-3) Sorting equation (1-3) indicate the probability of individual’s attachment to primary sector. In other words, it serves as selection criterion that sorts workers into primary or secondary segment according to their observed characteristics. ln Wip and ln Wis are both logs of wage associated to upper and lower tier respectively. X i and Di are independent variables. Then, p , s and represent the coefficients related to two regimes equations and sorting equation. Finally, pi , si and wi are considered as errors terms of three equations In fact, as Z * is a latent variable and non-observable, it may be defined through Wi : Wi ln Wip if Z* 0 (1-4) Wi ln Wis if Z* 0 (1-5) With respect to this specification, Z * is simply derived from utilities differences between primary and secondary segment. Thus, the probability that a worker has a job in primary sector is higher than the maximization of utilities associated to primary segment exceeds that of secondary segment. To establish the log likelihood function, some assumptions might be introduced. The strong hypothesis of this standard model, that is worth being further considered, concerns the actual form of error terms distribution. In fact, in this paper, errors terms follow normal distribution. Then, the log-likelihood function for this model is given by D pw D sw i pi si N pi i pp ss si 1 / 2 1 / 2 ln 1 pp 1 / 2 1/ 2 1/ 2 1 / 2 ss i i 2 pw pp 2 sw ss 1 1 2 pp 2 ss (1-7) It’s technically shown that the variance of error term in sorting equation has to be normalized to one since variance-covariance matrix requires an identification14. Regarding to the function (1-7), pw and sw are covariances between pi and wi and between si et wi , respectively; pp and ss are variances of error terms for primary and secondary wage equation. (.) and (.) are the normal density and accumulative distribution. 13 See Maddala (1983) for the original version of all endogenous switching methods. p 2 ps 2 pw2 14 The variance-covariance matrix described as follow : 2 Cov( p , s , w ) sp s 2 sw2 2 2 2 wp ws w Furthermore, the results given by switching model with unknown regime will be compared with those stimulated by the Ordinary Least Square method (OLS) in order to show which of both represent better the sample. To this end, the OLS has to be replaced by the log-likelihood method as so to make it comparable with the switching model. Thus the alternative hypothesis that is only one segment implies that there is only one wage equation. The log-likelihood (1-7) with these restrictions15 collapses to: ~ 1 / 2 Yi X~ i LFR ( ) 1/ 2 i 1 N (1-8) Maximization of log-likelihood functions must be made with sample selection as so to maintain the credibility of test. 3.2 Data selection Data from Labour Force Survey (LFS) for the years 2002 and 2003 are used for the econometric option mentioned above. The LFS is a nation-wide and representative survey collected annually by The National Statistics Office. The first LFS was conducted in 1963. Beginning in 1971, two rounds of the survey had been conducted each year: the first round enumeration was held during JanuaryMarch corresponding to the non-agricultural season and the second round during July-September coinciding with the agricultural season. From 1998 to 2000, the LFS had been undertaken 4 rounds a year; the first round in February, the second in May, the third and the fourth round in August and November respectively. Since 2001, the LFS has been monthly conducted. The data has been collected by using a series of questionnaires intended for more than 60 thousand of household a year. The LFS allows for the mains variables in relation to work conditions such as employment, unemployment, number of work hours, wage, industrial and professional type, education attainment and alike. Although this data is based on international standard in terms of concept, definition and classification, there are a large number of technical limits. At one point, it’s possible that an account of employed persons is overestimated with regard to numbers of work hours. This is due to the large definition of employed that refers to all persons who work for at least one hour for wage or not during a week [Anon Juntavich (2000) pp.07]. Then, since 2001, the classification in term of industrial and professional types has been modified as so to update the survey regarding to international classification changes. It’s thus difficult to compare the data between 1961-2000 and 2001-2004, particularly with respect to industrial and occupational classification. Finally, an accountability of unemployed suffers from a seasonally adjusted bias. According to those issues, my study is based on data from LFS for a year 2002 and 2003, considered as the most relevant survey in term of international classification. One of specificities of the switching model concerns a crucial assumption relatively to a job’s nonpecuniary characteristics. In fact, the model requires that non-pecuniary aspects might not influence workers’ choices of segment while those elements are actually important for people’s well being. The way to correct this gap is rending the population more homogeneous. In others word, a homogeneous group of people should hypothetically make the same evaluation of a job’s non-pecuniary characteristics. Both data concerns and model restriction lead to sample selection. The selection process tend to exclusively include workers in private enterprise, non agricultural, being in urban area, comprise between 15 and 64 years old. For males, the sample contains only heads of household in order to respect the homogeneity of workers. One should expect it to be harder to find evidence for the dual labour market among heads of household than mixed population. For females, representative individuals could be either head of household or spouse. With respect to work hours and wage, individuals considered might have at least 20 hours a week. This restriction arises from the same 15 It means that there is one set of parameters: ~s ~p ~; s p ; ss pp . assumption of homogeneous group. The wage is the hourly wage16 including all benefits related both to primary and secondary jobs. The selection of relevant independent variables could be pointed out as follow. Education attainment is one of the survey’s categorical variable. A number of years of schooling are computed according to Thailand’s educational classification. Experience is then constructed as potential experience and experience square is simply the product vector of this last one. I introduce also the variable potential experience multiplied by education attainment as complementary effect between experience and education17. Besides years of schooling, I introduce three dummy variables into switching equation such as highly skilled worker, size of firm and residence in Bangkok. In fact, the International Standard Classification of occupation-88 (ISCO-88) classifies all occupations according to skill levels18. In this analysis, highly skilled worker could be defined as persons whose jobs meet the third and the fifth skill level, namely (1) legislators, senior, (2) officials and managers, (3) Professionals, (4) Technicians and associate professionals. Thus, if worker has a mentioned job, highly skilled job = 1 and 0 otherwise. Regarding to size of firm variable, I follow the evidence from Suehiro and Wailerdsak (2004) that show high probabilities of large firms to promote internal labour market among mangers. If individual works in firm whose size is more than 50 persons, size of firm=1 and 0 otherwise. The last dummy variable concerns residence in Bangkok, the capital of Thailand, where there is a great concentration of economics activities. If worker reside in Bangkok, Bangkok=1 and 0 otherwise. 4. Results In this analysis, there are two steps of test for the existence of dual labour market. First, labour market must consist of two distinct wage equations rather than single function. To do so, results of estimates should confirm that two wage equation given by switching model with unknown regime fixe better than one standard equation set by the OLS. Then, relevant coefficients must allow seeing if returns to human capital in primary segment are strongly more than those in secondary segment. Moreover, this last segment should show that returns to human capital are closely nil. 4.1 Estimates results The maximization process of log-likelihood function is difficultly obtained. This is mainly due to the fact that optimizations depend largely on types of algorisms used. Some basic algorithms failed to reach the maximum of log-likelihood. Among basic optimization algorithms under the program Limdep version 719, I used two algorithms, namely BFGS for the fist run and Newton’s for reaching the maximum. Several starting values were tested in order to check that optimization process does not fail to unbounded area or inexistent maximization. Tables 1 and 2 show results of estimates for males and females in 2002 and 2003 respectively. 16 To compute hourly wage, monthly wage registered in LFS is divided by 4 as so to get a weekly wage and then numbers of works hours by week is used to divide weekly wage. 17 Futoshi(2004) shows that schooling and destination experience are complementary in migrants’ wage adjustment in Thai urban labor market. 18 See ILO (1990). 19 The basic algorithms in LIMDEP v.7 [see Green (1995)] are Broyden-Fletcher-Goldfarb-Shanno(BFGS); Dadidon-Fletcher-Powell (DEP); Steepest ascent; Newton’s and Berndt-Hall-Hall-Hausman (BHHH). Table 1: Switching regression model: males (2002-2003). OLS Primary 2002 β t β Constant Education (years) Experience (years) Experience2 Experience*Education Highly skilled worker Size of firm (>50) Residence in Bangkok Standard error Log-likelihood Log-likelihood ratio N Année 2003 Constant Education (years) Experience (years) Experience2 Experience*Education Highly skilled worker Size of firm (>50) Residence in Bangkok Standard error Log-likelihood Log-likelihood ratio N 0,7561 0,0556 0,0191 -0,0004 0,0015 9,222*** 9,347*** 3,746*** -5,562*** 5,683*** 0,1028 0,1080 0,0735 -0,0009 -0,0008 0,1131 28,636*** -539,7693 0,0670 8,023*** 11,277*** 3,444*** -4,520*** 5,325*** -0,0900 0,1285 0,0696 -0,0007 -0,0013 Secondary t 0,737 11,372*** 8,895*** -7,460*** -2,192* β 1,1860 0,0166 0,0057 -0,0002 0,0006 11,654*** 0,0543 -186,4610 Selection t 13,797*** 2,387** 1,109 -2,513** 2,135* 14,229*** β -1,1608 0,0180 t -8,782*** 1,304 1,0805 10,268*** 0,3417 5,400*** 0,3475 5,616*** Normalized to one 706,6166 1640 0,6579 0,0657 0,0171 -0,0003 0,0014 0,1162 30,619*** -642,4238 0,0855 722,5692 1875 Notes: *significant at 10%; ** significant at 5%; *** significant at 1%. t is t-student. -0,562 11,224*** 7,581*** -5,528*** -3,032*** 9,610*** 1,1172 0,0193 0,0095 -0,0002 0,0005 0,0558 -281,1392 11,701*** 2,432** 1,777 -3,033*** 1,656 12,086*** -1,3836 0,0447 -9,806*** 2,823*** 0,7632 8,735*** 0,3253 5,493*** 0,3492 6,020*** Normalized to one Table 2: Switching regression model: females (2002-2003). OLS 2002 β Constant Education (years) Experience (years) Experience2 Experience*Education Highly skilled worker Size of firm (>50) Residence in Bangkok Standard error Log-likelihood Log-likelihood ratio N 2003 Constant Education (years) Experience (years) Experience2 Experience*Education Highly skilled worker Size of firm (>50) Residence in Bangkok Standard error Log-likelihood Log-likelihood ratio N 0,8030 0,0547 0,0131 -0,0004 0,0013 0,0876 Primary t 11,802*** 11,239*** 2,844*** -5,784*** 5,451*** 29,1380*** -341,9806 β 0,5305 0,0879 0,0321 -0,0004 0,0005 0,0769 Secondary β t 2,900*** 7,716*** 2,396** -1,851 0,723 1,0592 0,0266 0,0052 -0,0003 0,0010 9,474*** 0,0555 Selection t 13,043*** 4,222*** 0,9590 -3,850*** 3,0190*** 15,856*** β -1,2322 0,0070 t -7,409*** 0,3880 0,6917 6,893*** 0,4509 6,850*** 0,2826 4,400*** Normalized to one -52,0109 579,9395 1698 0,8054 0,0558 0,0065 -0,0003 0,0018 0,1022 10,450*** 10,421*** 1,268*** -3,585*** 7,005*** 28,644*** -457,1117 734,2205 1641 Notes: *significant at 10%; ** significant at 5%; *** significant at 1%. t is t-student. 0,5924 0,0779 0,0263 -0,0003 0,0006 0,1344 3,482*** 7,042*** 2,365** -1,479 1,141 1,3158 -0,0019 0,0008 -0,0002 0,0009 14,806*** 0,0341 -90,0015 17,595*** -0,293 0,179 -2,836*** 3,257*** 13,152*** -2,1813 0,1250 -12,285*** 8,238*** 0,5536 4,554*** 0,5994 7,583*** 0,3891 5,189*** Normalized to one According to those tables, attention should be drawn to coefficients belonging to switching equation. At first glance, although most of those coefficients seem to be statistically significant at convention level for both males and females, coefficients of education variable for 2002 are significantly nil for all sex. It also means that selected variables are merely relevant with respect to sorting mechanism. It can be noticed that having a highly skilled job increase substantially the probability of being in primary sector. The positive coefficients related to variables size of firm and residence in Bangkok indicate the positive impact of the last ones on the probability of being classified in upper tier of labour market. However coefficients of education variables in sorting equation are rather low as compared to others. This result suggests that being more educated implies only slightly the probability of obtaining a primary job. Therefore, entry to primary segment depends not only on human capital, but also closely on other factors such as occupational and firm types and geographical area. Moreover, the complementary hypothesis with regard to relationship between education and experience is surprisingly contrary to what I expected. The coefficients of variable experience*education drawn from OLS method appear to be positively significant while those issues from switching model differ through segments. For instance, impact of this complementary on wage seems to be negative for male head-of-household in 2003 while it’s significantly positive for females in 2002 and 2003. However, the test results should clarify the existence of dual labour market. 4.2 Test results As notes above, to test the dual labour market hypothesis that there are two distinct markets, we need to show that primary wage equation is different from the wage equation of secondary sector. In this study, the test used remains non exhaustive as it will be further discussed. The standard approach concerns the likelihood ratio20 test used by Dickens and Lang. Such a method requires an alternative hypothesis that some coefficients have to be restricted. The problem arise is that some coefficients in switching model are not indentified such as two covariances of error terms in switching model. Dickens and Lang (1985a) suggest using Monte Carlo results that to determine whether a two equation model fits the data better than a single model, one could fixe a chi-squared distribution with degrees of freedom equal to the difference between the number of parameters in the unconstrained and constrained equations21. In the case of this study, the degrees of liberty are equals to 13: 6 parameters constraints to equality for two wag equations; 5 parameters constraints to zero in sorting equation and 2 non-indentified covariances. The log-likelihood ratio indicated in table 1 and 2 reveal that the twoequation model clearly fits the data better than the single-equation model. In fact, since 99 percent critical value of a chi-squared distribution with 13 degrees of freedom is equal to 34,53, all loglikelihood ratios remain largely greater than this critical value. This result supports the dual labour market hypothesis. However, it’s interesting to note that such a test had been criticized by Heckman and Hotz (1986) about the normality assumption. To answers to this criticism, Dickens and Lang (1992) applied a goodness of fit test and shown that they fail to reject the distributional assumption at the 0.05 level. The recent study by Boffoe-Bonnie allows for Weibull distribution that considers an assumption of the non-normality in error term. Although the two distributional forms generate the different percentage distribution of workers, this empirical approach appear to give the same conclusion as normal distribution model in term of the existence of dual labour market. The next step consists in verifying whether these equations resemble the prediction of dual labour market. In other words, we need to show that on the one hand primary segment give more returns to human capital than those in secondary segment and on the other hands, impact of human capital variables on wage is not significant. 20 The log-likelihood ratio test (LRT) could be mentioned as follow: N Max LRT 2 log Max 21 LFR i 1 N i LFUN i 1 2 log i Max Max LFR LFUN See also Gildfeld and Quint (1975). ILO, 1990: The Revised International Standard Classification of Occupations (ISCO-88). ILO, Geneva, 1990. Reference Becker, G. S. 1964. Human Capita, New York: Columbia University Press; 2nd edn, Chicago: Chicago university Press, 1975. Dickens, WT., Lang K.1985a. A test of dual labor market theory, American Economic Review 75:792–805. _________________.1985b. Testing dual Labour Market Theory: A reconsideration of the evidence, NBER working Paper, No, 1883, April, 1986. _________________.1987. A goodness of the fit test of dual labour market theory, NBER working paper, No.2350, August, 1986. _________________.1988. Labor market segmentation and the union wage premium, Review and Economics and Statistics 70:527–532. _________________. 1992. Labor market segmentation theory: Reconsidering the evidence, National Bureau of Economic Research Working Papers Series No. 4087. Doeringer, P.B., Piore, M. J. 1971. Internal Labour Market Manpower analysis, Lexington, Mass., D.C., Health and Company. Isra Sarntisart. 2001. Long term changes in income inequality in Thailand, Bangkok, working paper, Chulalongkorn university . Krongkeaw, M., Kakwani, N. 2003.The growth–equity trade-off in modern economic development: the case of Thailand, Journal of Asian Economics 14 (2003) 735–757. Manoley, W. F. 1999. Does Informality Imply Segmentation in Urban Labor Markets? Evidence from Sectoral Transitions in Maxico, The Word Bank Economic Review, Vol. 13, No.2, 275-302. Mincer, J. 1974. Schooling, Experience and Earnings, New York, National Bureau of Economic Research. Piore, M. 1970. Job and Training, in The state and the poor. Edited by S.H. Beer and R.E. Barringer. Cambridge, Mass.: Winthrop Press, 53-83. Pratap, S., Quintin, E. 2003. Are Labor Markets Segmented in Argentina? A semiparametric Approach, European Economic Review, 2006, 7, pp. 1817-1841. Schultz, T.W. 1971. Investment in Human Capital: The Role of Education and of Research, New York: Free Press. Wial, H. 1991. Getting a good job : Mobility in a segmented labor market, Industrial Relations, vol. 30, No.3.. World Bank. 2001. Thailand secondary education for employment: Volume I a policy note, Washington D.C, Report No. 22660-TH, World Bank.