Language and Literature

advertisement

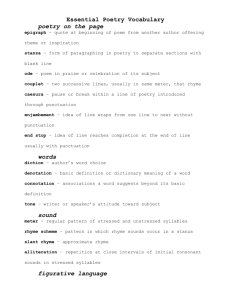

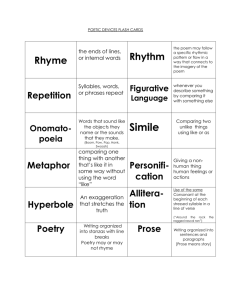

Chapter 9 Language and Literature 1. Style and Stylistics Style: variation in the language use of an individual, such as formal/informal style Literary style: ways of writing employed in literature and by individual writers; the way the mind of the author expresses itself in words 2 Stylistics “studies the features of situationally distinctive uses (varieties) of language, and tries to establish principles capable of accounting for the particular choices made by individual and social groups in their use of language.” (Crystal 1980) 3 Stylistics is the study of varieties of language whose properties position that language in context. For example, the language of advertising, politics, religion, individual authors, etc., or the language of a period in time, all belong in a particular situation. In other words, they all have ‘place’. 4 Stylistics also attempts to establish principles capable of explaining the particular choices made by individuals and social groups in their use of language, such as socialisation, the production and reception of meaning, critical discourse analysis and literary criticism. 5 Other features of stylistics include the use of dialogue, including regional accents and people’s dialects, descriptive language, the use of grammar, such as the active voice or passive voice, the distribution of sentence lengths, the use of particular language registers, etc. 6 Many linguists do not like the term ‘stylistics’. The word ‘style’, itself, has several connotations that make it difficult for the term to be defined accurately. However, in Linguistic Criticism, Roger Fowler makes the point that, in non-theoretical usage, the word stylistics makes sense and is useful in referring to an enormous range of literary contexts, such as John Milton’s ‘grand style’, the ‘prose style’ of Henry James, the ‘epic’ and ‘ballad style’ of classical Greek literature, etc. (Fowler, 1996: 185). 7 In addition, stylistics is a distinctive term that may be used to determine the connections between the form and effects within a particular variety of language. Therefore, stylistics looks at what is ‘going on’ within the language; what the linguistic associations are that the style of language reveals. 8 Literary Stylistics: Crystal (1987) observes that, in practice, most stylistic analysis has attempted to deal with the complex and ‘valued’ language within literature, i.e. ‘literary stylistics’. The scope is sometimes narrowed to concentrate on the more striking features of literary language, for instance, its ‘deviant’ and abnormal features, rather than the broader structures that are found in whole texts or discourses. For example, the compact language of poetry is more likely to reveal the secrets of its construction to the stylistician than is the language of plays and novels. 9 Levels of analysis Sound effects Vocabulary Phraseology Grammar Implicature 10 2. Foregrounding The 1960 dream of high rise living soon turned into a nightmare. 11 Four storeys have no windows left to smash But in the fifth a chipped sill buttresses Mother and daughter the last mistresses Of that black block condemned to stand, not crash. 12 The red-haired woman, smiling, waving to the disappearing shore. She left the maharajah; she left innumerable other lights o’ passing love in towns and cities and theatres and railway stations all over the world. But Melchior she did not leave. 2.1 What is ‘foregrounding’? In a purely linguistic sense, the term ‘foregrounding’ is used to refer to new information, in contrast to elements in the sentence which form the background against which the new elements are to be understood by the listener / reader. 14 In the wider sense of stylistics, text linguistics, and literary studies, it is a translation of the Czech aktualisace (actualization), a term common with the Prague Structuralists. In this sense it has become a spatial metaphor: that of a foreground and a background, which allows the term to be related to issues in perception psychology, such as figure / ground constellations. 15 The English term ‘foregrounding’ has come to mean several things at once: the (psycholinguistic) processes by which - during the reading act - something may be given special prominence; specific devices (as produced by the author) located in the text itself. It is also employed to indicate the specific poetic effect on the reader; an analytic category in order to evaluate literary texts, or to situate them historically, or to explain their importance and cultural significance, or to differentiate literature from other varieties of language use, such as everyday conversations or scientific reports. 16 Thus the term covers a wide area of meaning. This may have its advantages, but may also be problematic: which of the above meanings is intended must often be deduced from the context in which the term is used. 17 2.2 Devices of Foregrounding Outside literature, language tends to be automatized; its structures and meanings are used routinely. Within literature, however, this is opposed by devices which thwart the automatism with which language is read, processed, or understood. Generally, two such devices may be distinguished, deviation and parallelism. 18 Deviation corresponds to the traditional idea of poetic license: the writer of literature is allowed - in contrast to the everyday speaker to deviate from rules, maxims, or conventions. These may involve the language, as well as literary traditions or expectations set up by the text itself. The result is some degree of surprise in the reader, and his / her attention is thereby drawn to the form of the text itself (rather than to its content). Cases of neologism, live metaphor, or ungrammatical sentences, as well as archaisms, paradox, and oxymoron (the traditional tropes) are clear examples of deviation. 19 Devices of parallelism are characterized by repetitive structures: (part of) a verbal configuration is repeated (or contrasted), thereby being promoted into the foreground of the reader's perception. Traditional handbooks of poetics and rhetoric have surveyed and described (under the category of figures of speech) a wide variety of such forms of parallelism, e.g., rhyme, assonance, alliteration, meter, semantic symmetry, or antistrophe. 20 3. Literal language and figurative language Friends, Romans and Countrymen, lend me your ears… Anthony in Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar 21 3.1 Simile O, my luve is like a red, red rose, That’s newly sprung in June; O, my luve is like the melodie That’s sweetly play’d in tune. Robert Burns (1759-96) 22 3.2 Metaphor All the world’s a stage, And all the men and women merely players; They have their exits and their entrances. And one man in his time plays many parts, His acts being seven ages … William Shakespeare (1564-1616) 3.3 Metonymy There is no armour against fate; Death lays his icy hand on kings; Sceptre and Crown Must tumble down And in the dust be equal made With the poor crooked Scythe and Spade. James Shirley (1596-1666) 3.4 Synecdoche They were short of hands at harvest time. (part for whole) Have you any coppers? (material for thing made) He is a poor creature. (genus for species) He is the Newton of this century. (individual for class) Name the kind of trope: The boy was as cunning as a fox. ...the innocent sleep,... the death of each day's life,... (Shakespeare) Buckingham Palace has already been told the train may be axed when the rail network has been privatised. (Daily Mirror, 2 February 1993) Ted Dexter confessed last night that England are in a right old spin as to how they can beat India this winter. (Daily Mirror, 2 February 1993) 26 4. Analysis of literary language Foregrounding on the level of lexis Foregrounding on the level of syntax: word order, word groups, deviant or marked structures Rewriting for comparative studies Meaning Context Figurative language 5. The language of poetry Little Bo-peep Has lost her sheep And doesn’t know where to find them Leave them alone And they will come home Waggling their tails behind them Fair is foul and foul is fair Hover through wind and murky air Hark! The herald angels sing Glory to the newborn King! Long burned hair brushes Across my face its spider Silk. I smell lavender Cinnamon: my mother’s clothes. 5.1 Forms of sound patterning Rhyme Alliteration Assonance Consonance Reverse rhyme Pararhyme Repetition 30 Rhyme: two words rhyme if their final stressed vowel and all following sounds are identical; two lines of poetry rhyme if their final strong positions are filled with rhyming words. |Humpty |Dumpty |sat on a |wall |Humpty |Dumpty |had a great |fall |All the king’s |horses and |all the king’s |men |Couldn’t put |Humpty to|gether a|gain 31 32 Alliteration: repetition of the initial consonant of a word Magazine articles: “Science has Spoiled my Supper” and “Too Much Talent in Tennessee?” Comic/cartoon characters: Beetle Bailey, Donald Duck Restaurants: Coffee Corner, Sushi Station Expressions: busy as a bee, dead as a doornail, good as gold, right as rain, etc... Music: Blackalicious' “Alphabet Aerobics” 33 Assonance: Repetition of vowel sounds to create internal rhyming within phrases or sentences The sound of the ground is a noun. Hear the mellow wedding bells. (Poe) And murmuring of innumerable bees (Tennyson) The crumbling thunder of seas (Stevenson) That solitude which suits abstruser musings (Coleridge) Dead in da middle of little Italy, little did we know that we riddled some middle men who didn't do diddily. (Big Pun) 34 Consonance: The repetition of two or more consonants using different vowels within words. All mammals named Sam are clammy And the silken sad uncertain rustling of each purple curtain (Poe) Rap rejects my tape deck, ejects projectile / Whether jew or gentile I rank top percentile. (Hiphop music) 35 Reverse rhyme: C V C Coca-Cola; Hoola hoops Such storms can bring you to the brink of all you fear Restore what faith you can in faded hopes and feel Pararhyme (Frame rhyme): C V C Each sturdy steed-like soldier ranked the field With fearsome faces seldom seen defiled Rich Rhyme: C V C What does it avail you to prevail in every affair When nothing you’ve gained can be regained as spiritual fare 36 Repetition: “Words, words, words.” (Hamlet) “This, it seemed to him, was the end, the end of a world as he had known it...” (James Oliver Curwood) “We shall fight on the beaches, we shall fight on the landing grounds, we shall fight in the fields and in the streets, we shall fight in the hills… we shall never surrender.” (Winston Churchill) “What lies behind us and what lies before us are tiny compared to what lies within us.” (Ralph Waldo Emerson) 37 5.2 Stress patterning Iamb: 2 syllables, unstressed + stressed Trochee: 2 syllables, stressed + unstressed Anapest: 3 syllables, 2 unstressed + stressed Dactyl: 3 syllables, stressed + 2 unstressed Spondee: 2 stressed syllables Pyrrhic: 2 unstressed syllables 38 5.3 Metrical patterning Dimetre: 2 feet Trimetre: 3 feet Tetrametre: 4 feet Pentametre: 5 feet Hexametre: 6 feet Heptametre: 7 feet Octametre: 8 feet 39 5.4 Conventional forms of metre and sound Couplets: a pair of lines of verse, usually connected by a rhyme. It consists of two lines that usually rhyme and have the same meter. Whan that Aprille, with hise shoures soote, The droghte of March hath perced to the roote And bathed every veyne in swich licour, Of which vertu engendred is the flour; (from Geoffrey Chaucer: Canterbury Tales – General Prologue) 40 Quatrains: Stanzas of four lines Tyger! Tyger! burning bright In the forests of the night, What immortal hand or eye Could frame thy fearful symmetry? (from William Blake, “The Tyger”) 41 Blank verse: lines in iambic pentametre which do not rhyme Ye elves of hills, brooks, standing lakes and groves, And ye that on the sands with printless foot Do chase the ebbing Neptune, and do fly him When he comes back; you demi-puppets that By moonshine do the green sour ringlets make Whereof the ewe not bites; and you whose pastime Is to make midnight mushrooms, that rejoice To hear the solemn curfew; by whose aid, Weak masters though ye be, I have bedimmed The noontide sun, called forth the mutinous winds, And 'twixt the green sea and the azured vault Set roaring war - to the dread rattling thunder Have I given fire, and rifted Jove's stout oak With his own bolt;... (from Shakespeare: The Tempest, 5.1) 42 Sonnet: The term “sonnet” derives from the Provençal word sonet and the Italian word “sonetto,” both meaning “little song.” By the thirteenth century, it had come to signify a poem of fourteen lines that follows a strict rhyme scheme and specific structure. One of the most well known sonnet writers is Shakespeare, who wrote 154 sonnets. The proper rhyme scheme for an English Sonnet is: a-b-a-b / c-d-c-d / e-f-e-f / g-g 43 Let me not to the marriage of true minds (a) Admit impediments, love is not love (b) Which alters when it alteration finds, (a) Or bends with the remover to remove. (b) O no, it is an ever fixed mark (c) That looks on tempests and is never shaken; (d) It is the star to every wand'ring bark, (c) Whose worth's unknown although his height be taken. (d) Love's not time's fool, though rosy lips and cheeks (e) Within his bending sickle's compass come, (f) Love alters not with his brief hours and weeks, (e) But bears it out even to the edge of doom: (f) If this be error and upon me proved, (g) I never writ, nor no man ever loved. (g) (Shakespeare's Sonnet 116 ) 44 ROMEO: JULIET: ROMEO: JULIET: ROMEO: JULIET: ROMEO: If I profane with my unworthiest hand This holy shrine, the gentle fine is this: My lips, two blushing pilgrims, ready stand To smooth that rough touch with a tender kiss. Good pilgrim, you do wrong your hand too much, Which mannerly devotion shows in this; For saints have hands that pilgrim’s hands do touch, And palm to palm is holy palmer’s kiss. Have not saints lips, and holy palmers too? Ay, pilgrim, lips that they must use in prayer. O, then, dear saint, let lips do what hands do; They pray, grant thou, lest faith turn to despair. Saints do not move, though grant for prayer’s sake. Then move not, while my prayer’s effect I take. (from Shakespeare: Romeo and Juliet) 45 Free verse: styles of poetry that are not written using strict meter or rhyme, but that still are recognizable as poetry by virtue of complex patterns of one sort or another that readers will perceive to be part of a coherent whole. The yellow fog that rubs its back upon the window-panes, The yellow smoke that rubs its muzzle on the window-panes Licked its tongue into the corners of the evening, Lingered upon the pools that stand in drains, Let fall upon its back the soot that falls from chimneys, Slipped by the terrace, made a sudden leap, And seeing that it was a soft October night, Curled once about the house, and fell asleep. (from T. S. Eliot: The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock) 46 Limericks The word derives from the Irish town of Limerick. Apparently a pub song or tavern chorus based on the refrain “Will you come up to Limerick?” where, of course, such bawdy songs or ‘Limericks’ were sung. Limericks consist of five anapaestic lines. Lines 1, 2, and 5 of Limericks have seven to ten syllables and rhyme with one another. Lines 3 and 4 of Limericks have five to seven syllables and also rhyme with each other. 47 Variants of the form of poetry referred to as Limerick poems can be traced back to the fourteenth century English history. Limericks were used in Nursery Rhymes and other poems for children. But as limericks were short, relatively easy to compose and bawdy or sexual in nature they were often repeated by beggars or the working classes in the British pubs and taverns of the fifteenth, sixteenth and seventh centuries. The poets who created these limericks were therefore often drunkards! Limericks were also referred to as dirty. 48 Limerick poems have received incredibly bad press and dismissed as not having a rightful place amongst what is seen as ‘cultivated poetry’. The reason for this is three-fold: The content of many limericks is often of a bawdy and humorous nature. A Limerick as a poetry form is by nature simple and short – limericks only have five lines. And finally the somewhat dubious history of limericks have contributed to the critics attitudes. 49 Limericks by Edward Lear There was an Old Man with a beard, Who said, ‘It is just as I feared! Two Owls and a Hen, Four Larks and a Wren, Have all built their nests in my beard!’ 50 There was a Young Lady whose chin, Resembled the point of a pin; So she had it made sharp, And purchased a harp, And played several tunes with her chin. 51 5.5 The poetic functions of sound and metre Aesthetic pleasure Conforming to a form Expressing/innovating with a form Demonstrating skill, intellectual pleasure For emphasis or contrast Onomatopoeia 52 5.6 The analysis of poetry Info about the poem: poet, period, genre, topic, etc. Structure: layout, number of lines, length of lines, metre, rhymes, sound effects, etc. plus general comment on the poem 53 “Easter Wings”, by George Herbert (1593—1663) Lord, who createdst man in wealth and store, Though foolishly he lost the same, Decaying more and more, Till he became Most poore: With thee O let me rise As larks, harmoniously, And sing this day thy victories: Then shall the fall further the flight in me. 54 E. E. Cummings (1894-1962) l(a le af fa ll s) one l iness 55 r-p-o-p-h-e-s-s-a-g-r who S a)s w(e loo)k upnowgath PPEGORHRASS eringint(oaThe):l eA !p: rIvInG (r a .gRrEaPsPhOs) to rea(be)rran(com)gi(e)ngly ,grasshopper; 56 6. The language of fiction From realism to modernism 6.1 Modernist literature Modernist literature is defined by its move away from Romanticism, venturing into subject matter that is traditionally mundane--a prime example being The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock by T. S. Eliot. Modernist literature often features a marked pessimism, a clear rejection of the optimism apparent in Victorian literature. 58 A common motif in Modernist fiction is that of an alienated individual--a dysfunctional individual trying in vain to make sense of a predominantly urban and fragmented society. However, many Modernist works like T. S. Eliot's The Waste Land are marked by the absence of a central, heroic figure. 59 Modernist literature transcends the limitations of the Realist novel with its concern for larger factors such as social or historical change; this is largely demonstrated in “stream of consciousness” writing. Examples can be seen in Virginia Woolf's Kew Gardens and Mrs Dalloway, James Joyce's Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man and Ulysses, William Faulkner's The Sound and the Fury, and others. 60 Modernism as a literary movement is seen, in large part, as a reaction to the emergence of city life as a central force in society. Many Modernist works are studied in schools today, from Ernest Hemingway's The Old Man and the Sea, to T. S. Eliot's The Waste Land, to James Joyce's Ulysses and A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. 61 It had been an easy birth, but then for Abel and Zaphia Rosnovski nothing had ever been easy, and in their own ways they had both become philosophical about that. Abel had wanted a son, an heir who would one day be chairman of the Baron Group. By the time the boy was ready to take over, Abel was confident that his own name would stand alongside those of Ritz and Statler and by then the Baron would be the largest hotel group in the world. 62 Abel had paced up and down the colourless corridor of St. Luke’s Hospital waiting for the first cry, his slight limp becoming more pronounced as each hour passed. Occasionally he twisted the silver band that encircled his wrist and stared at the name so neatly engraved on it. He turned and retraced his steps once again, to see Doctor Dodek heading towards him. Jeffrey Archer: The Prodigal Daughter 63 There is the Hart of the Wud in the Eusa Story that wer a stage every 1 knows that. There is the hart of the wood meaning the veryes deap of it thats a nother thing. There is the hart of the wood where they bern the chard coal thats a nother thing agen innit. Thats a nother thing. Berning the chard coal in the hart of the wood. That’s what they call the stack of wood you see. The stack of wood in the shape they do it for chard coal berning. Why do they call it the hart tho? That’s what this here story tels of. Russell Hoban: Ridley Walker 64 Sir Tristram, violer d’amores, fr’over the short sea, had passen-core rearrived from North Armorica on this side the scraggy isthmus of Europe Minor to wielderfight his penisolate war: nor had topsawyer’s rocks by the stream Oconee exaggerated themselse to Laurens County’s gorgios while they went doublin their mumper all the time: nor avoice from afire bellowsed mishe mishe to tauftauf thuartpeatrick not yet, though venissoon after, had a kidscad buttended a bland old isaac: not yet, though all’s fair in vanessy, were sosie sesthers wroth with twone nathandjoe. Rot a peck of pa’s malt had Jhem or Shen brewed by arclight and rory end to the regginbrow was to be seen ringsome on the aquaface. 65 The fall (bababadalgharaghtakamminarronnkonnbron ntonner-ronntuonnthunntrovarrhounawnskawntoohoo hoordenenthur— nuk!) of a once wallstrait oldparr is retaled early in bed and later on life down through all christian minstrelsy. The great fall of the offwall entailed at such short notice the pftjschute of Finnegan, erse solid man, that the humptyhillhead of humself prumptly sends an unquiring one well to the west in quest of his tumptytumtoes: and their upturnpikepointandplace is at the knock out in the park where oranges have been laid to rust upon the green since dev-linsfirst loved livvy. (from James Joyce: Finnegans Wake) 66 6.2 Fictional prose and point of view I-narrators Third-person narrators Schema-oriented language Given vs New information Deixis 67 Schema-oriented language: different participants in the same situation will have different schemas, related to their different viewpoints. Shopkeepers and their customers will have shop schemas which in many respects will be mirror images of one another, and the success of shopkeepers will depend in part on their being able to take into account the schemas and points of view of their customers. 68 Morley railway station from viewpoint of Fanny: She opened the door of her grimy, branch-line carriage, and began to get down her bags. The porter was nowhere, of course, but there was Harry... There, on the sordid little station under the furnaces... (D. H. Lawrence: Fanny and Annie) unfavorable. 69 Given vs New information: narrative reference to everything in the fiction except items generally assumed by everyone in our culture (e.g. the sun) must be new, and hence should display indefinite reference. One evening of late summer, before the nineteenth century had reached one third of its span, a young man and woman, the latter carrying a child, were approaching the large village of Weydon-Priors, in Upper Wessex, on foot. (Thomas Hardy: The Mayor of Casterbidge) 70 Deixis: reference by means of an expression whose interpretation is relative to the (usually) extralinguistic context of the utterance, such as who is speaking the time or place of speaking the gestures of the speaker, or the current location in the discourse. Examples of deictic expressions in English: I, You, Now, There, That, The following, & Tenses 71 Because deixis is speaker-related it can easily be used to indicate particular, and changing, viewpoint. Mr Verloc heard the creaky plank in the floor and was content. He waited. Mrs. Verloc was coming. 72 6.3 Speech presentation Direct speech (DS) Free indirect speech (FIS) Indirect speech (IS) Narrator’s representation of speech acts (NRSA) Narrator’s representation of speech (NRS) 73 (1) He thanked her many times, and said that the old dame who usually did such offices for him had gone to nurse the little scholar whom he had told her of. (2) The child asked how he was,and hoped he was better. (3) “No,” rejoined the schoolmaster, shaking his head sorrowfully, “No better. (4) They even say he is worse.” (Charles Dickens: The Old Curiosity Shop ) 74 6.4 Thought presentation Narrator’s representation of thought (NRT) Narrator’s representation of thought acts (NRTA) Indirect thought (IT) Free indirect thought (FIT) Direct thought (DT) Stream of consciousness 75 “He will be late”, she thought. (DT) She thought that he would be late. (IT) He was bound to be late! (FIT) He spent the day thinking. (NRT) She considered his unpunctuality. (NRTA) He will be late … 76 Stream of consciousness Filthy shells. Devil to open them too. Who found them out? Garbage, sewage they feed on. Fizz and Red bank oysters. Effect on the sexual. Aphrodis. (sic) He was in the Red bank this morning. Was he oyster old fish at table. Perhaps he young flesh in bed. No. June has no ar (sic) no oysters. But there are people like tainted game. Jugged hare. First catch your hare. Chinese eating eggs fifty years old, blue and green again. Dinner of thirty courses. Each dish harmless might mix inside. Idea for a poison mystery. (James Joyce: Ulysses ) 77 6.5 Prose style Authorial style: way of writing recognizable across a range of texts written by the same writer Text style: linguistic choices which are intrinsically connected with meaning and effect on the reader Text style of a book Text style of a writer 6.6 Analyzing the language of fiction Lexis/vocabulary Grammatical organization Textual organization Figures of speech Style variation Discoursal patterning Viewpoint manipulation 79 7. The language of drama Drama as poetry Drama as fiction Drama as conversation 80 7.1 Analyzing dramatic language Turn quantity and length Exchange sequence Production errors The cooperative principle Status marked through language Register Speech and silence 81 Turn: Because conversations need to be organised, there are rules or principles for establishing who talks and then who talks next. This process is called turn-taking. Two guiding principles in conversations: Only one person should talk at a time. We cannot have silence. The transition between one speaker and the next must be as smooth as possible and without a break. 82 Ways of indicating that a turn will be changed: Formal methods: for example, selecting the next speaker by name or raising a hand. Adjacency pairs: for instance, a question requires an answer. Intonation: for instance, a drop in pitch or in loudness. Gesture: for instance, a change in sitting position or an expression of inquiry. The most important device for indicating turntaking is through a change in gaze direction. 83 The rules of turn-taking are designed to help conversation take place smoothly. Interruptions in a conversation are violations of the turn-taking rule. Interruption: where a new speaker interrupts and gains the floor. Butting in: where a new speaker tries to gain the floor but does not succeed. Overlaps: where two speakers are talking at the same time. 84 Minimal responses: Responses such as mmmm and yeah. These are not interruptions but rather are devices to show the listener is listening, and they assist the speaker to continue. They are especially important in telephone conversations where the speaker cannot see the listener's eyes and hence must rely on verbal cues to tell whether the listener is paying attention. 85 There is some evidence that women tend to use minimal responses more than men, and this is a possible reason why, in mixed conversations, men talk more than women. With the encouragement of these minimal responses, men often continue to talk, and without the encouragement of these minimal responses, many women will stop talking. 86 Story-telling within a conversation is indicated by some kind of preface. This is a signal to the listener that for the duration of the story, there will be no turn-taking. Once the story has finished, the normal sequence of turn-taking can resume. Young children, in learning about this convention, have to be asked not to interrupt when someone is telling a story within a conversation. 87 7.2 Analyzing dramatic texts Paraphrasing Commentating Words Grammar Meaning Conversation Using theories 8. The cognitive approach to literature Going There is an evening coming in Across the fields, one never seen before, That lights no lamps. Silken it seems at a distance, yet When it is drawn up over the knees and breast It brings no comfort. Where has the tree gone, that locked Earth to the sky? What is under my hands, That I cannot feel? What loads my hands down? 89 Cognitive analysis What are the main attractors at the beginning of the poem? What is the figure (trajectory) and ground (landmark) in the first two stanzas? Based on the above, what then, or who, is going? 90 See Textbook, pp. 237-240, for a detailed analysis of the poem ‘Going’. 91