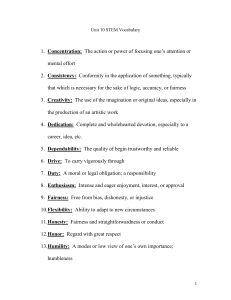

and “justice” - Cal State LA

advertisement

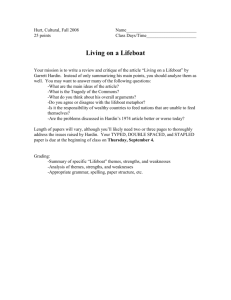

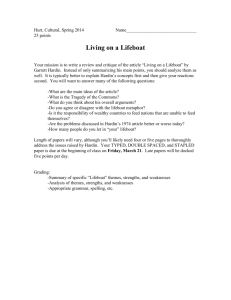

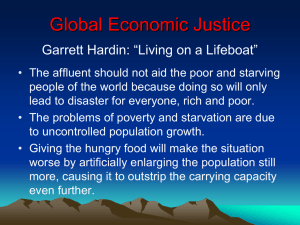

POLS 374 Foundations of Global Politics People and Justice Lecture People and Justice • Is global justice possible? • If it is, what would it involve? • What would be required to achieve it? 2 People and Justice Defining justice • When thinking about how to define justice, there are three basic approaches used by scholars, which we can classify as: (1) Distributive justice (2) Justice as fairness (3) Justice as rights 3 People and Justice Normative arguments • Before we begin a discussion of justice it is important to understand that any discussion of this issue is inherently normative, which means what? 4 People and Justice Normative arguments • A normative discussion is a discussion of what is right or ethical. To put it simply, it’s about deciding what constitutes a “good place to live” or a “good society,” as opposed to merely accepting the world as it is. Normative arguments are, in this sense, about how we should go about building the best possible world. 5 People and Justice Normative arguments • Normative arguments, not surprisingly, are generally controversial. They are controversial because reasonable people will almost always disagree on what is “moral,” “ethnical” or “good.” And, even if they can agree on basic principles, they may fundamentally disagree on how to achieve a better world. 6 People and Justice Normative arguments • Normative arguments are also controversial for a less obvious reason: in the social sciences, many scholars are uncomfortable talking about what ought to be; instead, they are ostensibly only concerned with what is. That is, some scholars believe that their primary duty is to discover how the world really works, to identify purely objective forces and dynamics. They would prefer to leave normative questions to “philosophers.” 7 People and Justice Normative arguments • One more point: Normative questions have profound political implications. As we’ll see in our discussion that follows, how we as a society answer normative questions has clear implications with regard to how resources are used and distributed and how power is exercised at the domestic, international, and global levels. This is one of the underlying points the authors are attempting to make in their chapter. 8 People and Justice Justice as distribution • This position is basically about the distribution of material goods, and revolves around the question: Is it moral for some people to have much more than they need, while others don’t have enough to even survive? • What do you think? 9 People and Justice Justice as distribution • The answer to this question, of course, is subject to a great deal of debate. In the chapter, the authors give us two, somewhat exaggerated perspectives of this debate, one by Peter Singer the other by Garrett Hardin. 10 People and Justice Justice as distribution • Singer’s Argument: Summed up in the following sentence: “If it is in our power to prevent something bad from happening, without thereby sacrificing anything of comparable moral importance, we ought, morally, to do it.” 11 People and Justice Justice as distribution • Singer’s reasoning based on philosophical position of “marginal utilitarianism.” • Definitional note: Utilitarianism is the doctrine or belief that the greatest good of the greatest number should be the purpose of human conduct (originally proposed by Jeremy Bentham. 12 People and Justice Justice as distribution • What do you think of Singer’s basic position? Any problems? Any objections? 13 People and Justice Justice as distribution • What do the authors say? • The authors point out a number of obvious practical and philosophical problems with Singer’s basic position, but they also agree that his argument raises troubling questions: What do we owe morally to those who are neither family nor members of any out communities of obligation, such as fellow citizens? We could rephrases this to say, “Do we have any moral obligations to those living outside our borders?” 14 People and Justice Justice as distribution • If we hem and haw on these questions—if we say, for example, that we have an obligation, but that we have more an obligation to our fellow citizens (none of whom we may know in any meaningful sense of the word), are we not just moral relativists? And aren’t we told by religious and even political leaders that moral relativism is wrong? 15 People and Justice Justice as distribution • On the other end of the spectrum is Garrett Hardin, who wrote a direct response to Singer’s position in an article called, “Lifeboat ethics: The case against helping the poor.” 16 People and Justice Justice as distribution • Hardin’s Argument: We cannot save everyone, so we must save ourselves. This is the responsible and the moral thing to do. 17 People and Justice Justice as distribution • Hardin uses the metaphor of the lifeboat to illustrate his position: He asks you to imagine that you and several others are adrift at sea in a lifeboat. The lifeboat is basically full and has sufficient food and water to last until everyone in the boat is rescued. In the water around you are a large number of people who can still swim, but eventually will drown if they are not saved (i.e., pulled into your lifeboat). So what should be done? What will happen if the people in the lifeboat start to pull others in? 18 People and Justice Justice as distribution • According to Hardin, the situation is clear: pulling people in may result in the lifeboat sinking; then everyone will die. Alternatively, pulling only a few people in, means you will less food and water and thereby diminish everyone’s chances for survival. Beyond this, though, is the question of who should be saved? 19 People and Justice Justice as distribution • Connecting this metaphor to the real world, Hardin argues that the rich countries simply don’t have the resources to save the poorer countries; moreover, whatever help is extended will likely only exacerbate an already bad situation by encouraging poor countries to produce more children. 20 People and Justice Justice as distribution • • What do you think of Hardin’s position? Even if you disagree, isn’t it true that no matter how uncomfortable we may be with his conclusions, most of us tacitly if not explicitly accept this his position? 21 People and Justice Justice as distribution • One more question: Even if Hardin is right about how most of us accept the position of protecting our own—of having no moral or other obligation to anyone who is not a bona fide, legal citizen of our country—is this really a justifiable moral position? 22 People and Justice Justice as distribution • One point on the logic of Hardin’s position: To a large extent, Hardin’s position is dependent on a zero-sum view of the world’s resources. He assumes, in other words, that the world’s resources are inherently limited and largely fixed, which implies that if the rich give something up, it means that we have less and somehow else has more 23 People and Justice Justice as distribution • Consider the metaphor of a sliced pie: If someone gets a bigger piece it necessarily leaves everyone else with less. 24 People and Justice Justice as distribution • The problem, however, is that wealth per se is not a limited resource, and food and other resources are not “fixed slices” either. For example, the production of food, over the past century, has more than kept up with the increase in people. It’s also important to understand that the world’s population, while it may be increasing, is increasing in part precisely because of poverty. 25 People and Justice Justice as distribution • • In other words, as poverty in poor countries decreases, it is certainly possible that the growth rate in population will also decrease. On this point, consider the case of Japan: As the country’s prosperity increased, the birth rate declined dramatically. Today, in fact, Japan’s overall population is shrinking at a fairly fast rate. 26 People and Justice 27 People and Justice Justice as distribution • It is important to understand that defining justice simply in terms of the allocation of material resources is a limited, and some might say, fatally limited perspective. • Others argue that, before we talk about distributive justice, we need to talk about why things are the way they are. That is, why do such vast inequalities in control over resources exist in the first place? What are the “rules” or practices that have created and maintained the obvious disparities that exist in the world? 28 People and Justice Justice as fairness • Some scholars, most notably John Rawls, argue that we need to understand that societies are organized in ways that tend to institutionalize injustices so that, for example, the unequal distribution of resources is largely pre-determined. That is, the rich have more because the rules of the system essentially guarantee that they’ll have more. 29 People and Justice Justice as fairness • To Rawls and others, then, it is not the unequal distribution of resources per se that is the problem; instead, it is an unfair, highly biased system of rules that is. • Recognizing this is important, for it allows us to take a different approach to justice. To Rawls, this approach centered on identifying the fundamental principles that would increase the level of fairness in society. Moreover, once its members recognized the centrality of such principles in seeking and achieving just outcomes, they would willingly accept those principles and the outcomes, however unequal the results. 30 People and Justice Justice as fairness • To see how this might be achieved, Rawls devised a thought experiment, which he called “decision-making from the original position, behind a veil of ignorance.” 31 People and Justice Justice as fairness • Imagine this: a situation in which no one knows anything about his own circumstances: his wealth, education, lineage, skin color, nationality, and so on. Rawls assumed that this set of circumstances would most clearly reflect an “original position,” that is a position in which no one had an advantage deriving from an “accident of birth” • The situation of not knowing anything about your original circumstances also reflects the “veil of ignorance,” which guarantees that all decisions about distribution will be made “disinterestedly,” that is, people will make decisions based on what is right rather than on what would be best for themselves. 32 People and Justice Justice as fairness • With this in mind, a group is asked to divide the riches of a society or the world. How would this be done? • Rawls argues that it is likely that such a group would decide to divide the wealth equally. Everyone would consider this the fairest distribution of resources, and because of this, inequalities that may arise after the original distribution of resources are also considered fair and just. 33 People and Justice Justice as fairness • Of course, the real world is nothing like the situation Rawls describes: We all start off in different original positions: some of us are born into wealthy families, some into poor families, some of us are born in rich countries, some in utterly poor countries; some of us born with intelligence or good looks, or some other genetic endowments that give us tremendous advantages or disadvantages over others. • These original endowments will, over time, result in inequality; some of us can also use our endowments to increase inequality (to get more for ourselves at the expense of others). At the same time, these circumstances are not necessarily considered unfair; after all, the people who were lucky enough to be born in the right place at the right time with the right attributes didn’t do anything wrong. Why should they then suffer just because others weren’t quite as lucky? 34 People and Justice Justice as fairness • This wasn’t the point Rawls was trying to make in his thought experiment; rather his goal was to derive principles of justice about which everyone could agree, regardless of their original positions. • Rawls concluded that two principles follow from this exercise: first, an equality of basic rights, and second, what he called the “difference principle.” The difference principle regards any inequality as unjust unless its removal makes worse the situations of the worst-off members of society. 35 People and Justice Justice as fairness • Rawls, it is important to understand, is a philosopher first and foremost; for this reason, perhaps, he didn’t offer any concrete ways to achieve a just society; instead, he only hoped that recognition of these rules of fairness would stimulate discussion and lead to practical principles that would create a more just society. To a large extent, he was successful: since he originally published his ideas 30 years ago, there has been an immense amount of debate on the principles of justice and fairness 36 People and Justice • A few aspects of this debate are covered in the remaining sections of the chapter, which cover such issues as “Justice as rights,” “justice as opportunity,” and “justice as recognition, respect, and dignity” 37 People and Justice • There is a lot of stuff covered in these three sections, probably too much for us to digest in class (really, we could devote a whole quarter to a discussion of justice) • So instead of covering each of these three sections in detail, let me highlight a few general points. 38 People and Justice • First, it is important to understand that, in any discussion of justice, there are a number of underlying tensions or contradictions that can complicate the discussion immensely. • Consider the question of human rights: Human rights are based on two kinds of rights, “positive liberty,” that is the freedom to do as we please, and “negative liberty,” that is, the freedom from control by outsiders. 39 People and Justice • Yet, to have positive liberty, there have to be rules that control what individuals can do. How, for example, can you have freedom of expression if someone else immediately beats you up for speaking your mind? Yet, in controlling the freedom of others to “beat up” whomever they please, we are limiting liberty. At the extremes, positive liberty erases negative liberty and vice versa. • This tells us that “rights” and “justice” can never be absolute. 40 People and Justice • Second, and in a strongly related vein, justice or rights require some sort of coercive entity(that is, states) capable of enforcing law. This creates a paradox: states are often the worst offenders of rights, but they are also necessary for rights to exist • This creates all sorts of practical as well as philosophical questions. How, for example, is it possible to transcend national borders to achieve a sort of universal rights? Is this even desirable? 41 People and Justice • Consider this example: What happens when one country’s definition of justice contradicts a supposedly universal standard of human rights? On this point, consider the issue of the death penalty, which is considered just punishment in the United States but a violation of human rights by most other countries in the world. Or how about torture? Torture is condemned by international laws, norms, and treaties, but the Bush administration continues to insist that has a right and duty to use any means necessary to extract information from enemy combatants. 42 People and Justice • Third, discussions of justice cannot be divorced from the larger social context. For example, there are a number of scholars who say that justice does not require equality in outcomes (re “justice as opportunities” or “justice as fairness”). In the abstract, these are reasonable arguments, but they cannot hold water in the real world. On this point, consider what John Isbister had to say (quoting from pp. 135-6): 43 People and Justice • “This reasoning [about justice] leads to the possibility that equality of opportunity actually requires equal outcomes. This possibility exists because we live our lives over a period of years, our generations overlap, and our societies continue over time. My opportunities are determined in large measure by the resources—including economic, educational, technological, and moral resources—given to me by my parents and by my society. If my parents and society are vastly different in their access to these resources from yours, you and I will be unequal at the starting blocks. Until each person has an equal opportunity to develop his or her talents—something that cannot exist while the distribution of outcomes in the world remains unequal—we cannot be equal at the starting line. 44 People and Justice • While Isbister may make a good point, his argument, too, has all sorts of practical and philosophical problems: Would making the starting line the same for all disadvantage others (i.e., those that already were in front)? 45 People and Justice • Fourth, given the foregoing discussion, the last point I want to highlight is simply this: Discussion about justice can make your head hurt because they end up becoming too complicated, too messy, and just too hard to resolve. Plus, as the authors note, too many philosophers fall into the old “ought-is” trap. That is, they argue about the need for social change without specifying how this might be accomplished. To be fair, this isn’t how many political philosophers see their job: their job is to conceptualize the conditions under which a particular objective might be achieved; it is the job of other social scientists to discover the lever that could “move the world.” 46 People and Justice • What, then, is the solution? 47 People and Justice • The authors don’t necessarily offer the solution, but they offer us a map for finding the right path to a solution. • They do this, ironically, by discussing another set of philosophical positions, between communitarianism and cosmopolitanism 48 People and Justice • Cosmopolitanism is reflected in Singer’s position, while communtarianism is reflected in the position of Hardin. • In communitarian view, justice is something that is inherently limited to fellow citizens: people only have a right and duty to protect their own. This implies that we can, without shame, turn our back on injustice when it is committed by or against noncitizens. They are simply not our concern. 49 People and Justice • In Singer’s extreme cosmopolitan view, everyone is deserving of rights essentially without limits. But, according to the authors, this is a non-starter. It’s a non-starter, in part, because Singer’s view of rights is simply to abstract. Other cosmopolitans, however, provide a more grounded approach. • On this point, the authors are particularly interested in the work of Onora O’Neill. 50 People and Justice • Unlike Singer, O’Neill focuses on obligations as opposed to rights. As O’Neill explains it, “There are reasons enough to show that obligations provide the more coherent and more comprehensive starting point for thinking about ethical requirements, including the requirements of justice. Although the rhetoric of rights has a heady power, and that of obligations and duties few immediate attractions, it helps to view the perspective of obligations as fundamental if the political and ethical implications of normative claims are to be taken seriously. 51 People and Justice • Obligations, in short, are more personal. When speaking of obligations, moreover, we immediately start to focus on agency: we must act in order to be just and achieve justice, and we must do so regardless of states, governments, or even co-nationals. Better yet, we should do so with others, as a collective political project. 52 People and Justice • This last point, although not one the authors end their chapter with, helps us tie everything discussed thus far to the relationship between justice and people. In an important sense, the authors are suggesting that justice, whether at the local, national, regional, international, or global levels starts with the actions of individuals acting alone and, better yet, in groups. 53 People and Justice • Ultimately, as they put it, “Justice demands that we believe all our fellow human beings are worthy of dignity and respect; that we act in ways that facilitate and foster dignity and respect among human beings; and that we provide the material necessities that enable people to live dignified lives worth of respect. Indeed, we are obligated to do these things and also to help to construct a discourse that will propagate justice and embed it in institutions at every level of life.” 54