Innovation and innovation policies in developing countries

advertisement

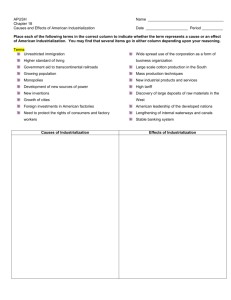

Industrial policy: history, theory and empirical evidence Michele Di Maio University of Naples Parthenope December 12, 2014 HDFS Master, University of Roma Tre Outline 1. The importance of manufacturing for economic development 2. The return of Industrial Policy (IP) 3. What is IP? 4. Theoretical justification(s) for IP 5. Historical experiences 6. Empirical evidence (international trade) 7. A special case: innovation policy Outline 1. The importance of manufacturing for economic development 2. The return of Industrial Policy (IP) 3. What is IP? 4. Theoretical justification(s) for IP 5. Historical experiences 6. Empirical evidence (trade) 7. A special case: innovation policy The importance of manufacturing for economic development Two stylized facts: 1. Economic development requires structural change from low to high productivity activities 2. Virtually all cases of high, rapid and sustained economic growth in modern economic development have been associated with industrialization, particularly growth in manufacturing production The importance of manufacturing for economic development The strategic role of manufacturing in the development process can be ascribed to a variety of factors. 1. manufacturing has historically been the main source of innovation in modern economies 2. strong (forward and backward) linkages and spill-over effects associated with manufacturing activities. 3. the share of manufactures in total household expenditure increases as per capita income rises while the share of agriculture decreases (Engel’s law). 4. manufacturing has a higher potential for employment creation relative to agriculture and traditional services. – diminishing returns to scale in agriculture (due to fixed factors such as land) implies that the opportunities for employment growth in the sector are limited. The manufacturing sectors has no this limitation and, as a country's population grows and urbanization takes place, can absorb labour displaced from agriculture Outline 1. The importance of manufacturing for economic development 2. The return of Industrial Policy (IP) 3. What is IP? 4. Theoretical justification(s) for IP 5. Historical experiences 6. Empirical evidence (trade) – evidence on infant-industry protection – cross-country evidence on tariffs, trade, and growth – “soft” versus “hard” IP 7. A special case: innovation policy The return of Industrial Policy • A prominent feature of developing countries economies (especially African ones) is the significant process of deindustrialization – Africa's gross domestic product (GDP) fell from 15 per cent in 1990 to 10 per cent in 2008. The most significant decline was observed in Western Africa, where it fell from 13 per cent to 5 per cent over the same period. • As a reaction to this state of affair, there has been an increasing commitment of governments to support industrialization as part of a broader agenda to diversify the economy through industrial policy. The return of Industrial Policy: examples • • • • • South African government (2007) adopted the National Industrial Policy Framework (NIPF). Objetives: diversifying the production and export structure and promoting labour absorbing industrialization. Industrialization is a component also of recent national development programmes of Egypt, Ethiopia, Kenya, Namibia, Nigeria and Uganda 2001 - The New Partnership for Africa's Development (NEPAD) identified economic transformation through industrialization as a critical vehicle for growth and poverty reduction in the region 2008 - Adoption of Plan of Action for the Accelerated Industrial Development of Africa (AIDA) 2010 - ECOWAS adopted the West African Common Industrial Policy (WACIP). – The objectives of WACIP are as follows: to diversify and broaden the region's industrial production by progressively raising the processing of export products by an average of 30% by 2030; to progressively increase the manufacturing industry's contribution to regional GDP to an average of over 20% in 2030, from its current average of 6%; to improve intra-community trade from the present 13% to 40% by 2030; to expand the volume of exports of manufactured goods from the current 0.1% to 1% by 2030. The return of Industrial Policy • This policy change has been accompanied by an increasing agreement among scholars on the fact that - beside the creation of a competitive market environment - governments of developing countries should also play a proactive role in facilitating structural transformation and industrial upgrading • While it is now clear that industrial policy (IP) is back in both the political and economic discourse, it is not all clear how to design an effective IP. • In fact, there are several factors that may make IP worse than the problems it aims to solve. • The first step is to understand what is the meaning of IP Outline 1. The importance of manufacturing for economic development 2. The return of Industrial Policy (IP) 3. What is IP? 4. Theoretical justification(s) for IP 5. Historical experiences 6. Empirical evidence (trade) 7. A special case: innovation policy What is Industrial Policy? (1) • There are several different possible definitions for IP. • All refer to the role of government in influencing the economic structure. • Pack (2000) defines IP as: government actions designed to target specific sectors to increase their productivity and their relative importance within the manufacturing sector. • Harrison and Rodigues-Clare (2010): any government intervention which shifts incentives away from policy neutrality. What is Industrial Policy? (2) • In other definitions, IP has an even more ample set of objectives, usually to enhance productivity, competitiveness, and overall economic growth. – IP comprises any government measure to promote or prevent structural change (Curzon Price , 1981) • One important cause of structural change is international trade. This is why IP is sometimes referred to as the set of policies aiming at ’defy’ the country comparative advantage and to develop its ’latent’ comparative advantage (Amsden, 2001; Chang, 2002). • Some sources give IP even more ambitious objectives: – to promote growth trying to shape structural change in ways that are socially inclusive and environmentally sustainable (UNIDO, 2011) What is Industrial Policy? (3) • The more general the objectives, the larger the set of measures which can be considered as part of IP. • According to Cimoli et al (2009), IP includes: i) innovation and technology policies; ii) education and skill formation policies; iii) trade policies; iv) targeted industrial support measures; v) sectoral (competitiveness) policies; vi) competition regulation policies. • Somehow different is the approach of Rodrik (2007) who defines IP as a process involving a ’dialogue’ between the state and the private sector to generate information for identifying and removing the binding constraints to development Industrial Policy: our definition • We define IP as the set of government measures - targeted at specific industries or firms - implemented with the objective to support the development and upgrading of industrial output (thus not limited to manufacturing sector). • For this reason, IP naturally includes a large set of policies belonging to different domains of intervention, namely: – – – – – – innovation and technology policies education and skills formation policies trade policies targeted industry support measures competitiveness policies competition and anti-trust regulation Outline 1. The importance of manufacturing for economic development 2. The return of Industrial Policy (IP) 3. What is IP? 4. Theoretical justification(s) for IP 5. Historical experiences 6. Empirical evidence (trade) 7. A special case: innovation policy When IP does makes sense in theory • The theoretical justification for IP is based on the fulfillment of three conditions: 1. some market failure is present (e.g., sector level externalities); 2. the firm/sector is potentially competitive in the international markets; 3. the discounted future benefits of intervention exceed the costs of the distortion. When IP does makes sense in theory Baseline: Under perfect competition, Government intervention is always bad ! When IP does makes sense in theory The theoretical justification for IP is based on the fulfillment of three conditions: 1. some market failure is present (e.g., sector level externalities); 2. the firm/sector is potentially competitive in the international markets; 3. the discounted future benefits of intervention exceed the costs of the distortion. When IP does makes sense in theory The theoretical justification for IP is based on the fulfillment of three conditions: 1. some market failure is present (e.g., sector level externalities); 2. the firm/sector is potentially competitive in the international markets; 3. the discounted future benefits of intervention exceed the costs of the distortion. Market failures There are three main types of market failures. 1. the existence of a sector level positive (technology or demand) externality 2. informational externality related to the difference between the private and the social benefit in exploring the profitability of a new activity. 3. investment coordination failure: because of a lack of required investments in related actives—the private sector investment is sub-optimal. When IP does makes sense in theory The theoretical justification for IP is based on the fulfillment of three conditions: 1. some market failure is present (e.g., sector level externalities); 2. the firm/sector is potentially competitive in the international markets; 3. the discounted future benefits of intervention exceed the costs of the distortion. When IP does makes sense in theory The theoretical justification for IP is based on the fulfillment of three conditions: 1. some market failure is present (e.g., sector level externalities); 2. the firm/sector is potentially competitive in the international markets; 3. the discounted future benefits of intervention exceed the costs of the distortion. When IP does not make sense in theory Two main arguments against the use of IP in developing countries: 1. even in the presence of imperfect markets, there is no reason to suppose that the government has better access to information with respect to the market. Since government information is necessarily limited, good selectivity is impossible – This implies - for instance - that the “picking winners” strategy is deemed to fail 2. any government measure (e.g., investment support, tax exemptions, etc.) creates rents. Firms find it profitable to (legally or not) invest their resources to obtain them. This is a wasteful activity that also distorts allocation of resources because it makes competition between firms unfair. Outline 1. The importance of manufacturing for economic development 2. The return of Industrial Policy (IP) 3. What is IP? 4. Theoretical justification(s) for IP 5. Historical experiences 6. Empirical evidence (trade) 7. A special case: innovation policy Historical experiences • We look at the historical experiences to understand the effects of IP • Past successful experiences 1. England (1800); Germany (1880); USA (1900) 2. 1960s: NICs (South Korea, Taiwan, Singapore, Hong Kong) • We focus on two different set of countries 1. African countries 2. BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa) Industrial Policy in Africa Industrial policy in Africa This section has two objectives: 1. To provide a survey of the literature on IP in Africa (historical and comparative perspective) 2. To suggest some policy recommendations based on the analysis of new approaches to industrialization Outline 1. Industry in Africa: some stylized facts 2. IP in Africa: a very brief historical overview 3. The new world, the new rules and IP in Africa today 4. What are the main IP options for African countries? Industry in Africa: problems and perspectives • African Export – nearly 75% are primary products – the composition of African exports to other developing countries has shifted towards primary products. • Primary products – production is capital intensive often poorly linked to other sectors – prices are set at the world level and characterized by high volatility • The increasing concentration of Africa’s production and exports on primary commodities casts some doubts on the potential for future growth in the region. • The type of product a country exports matters for long-term growth Industry in Africa: problems and perspectives • The experience of other emerging countries (i.e. East Asia and Latin America countries) show that industrialization has been the engine of growth • IP is needed to foster industrialization in Africa. • The failure of past industrialization strategies in Africa calls for a renewed developmental IP • Are there still lessons to be learned from the past? IP in Africa: historical overview The Developmental State in Africa – since the 1950s African governments implemented a number of measures to promote industrialization. – this process which was characterized by an Import Substitution Industrialization (ISI) strategy to development. – governments • offered protection to domestic firms • used a range of policy measures to implement protectionist trade policies (tariff and nontariff barriers, such as quotas and licenses • nationalised foreign firms and made large public investment IP in Africa: historical overview • Why did the Developmental State (DS) performance has been so different in NICs and in Africa? • Differences in initial conditions and in the characteristics of the policies adopted – initial conditions (quality of education and technological knowledge) – governments • offered protection to domestic firms – (little discrimination between activities, no time limit and no requirements of international competitiveness) • used a range of policy measures to implement protectionist trade policies (tariff and nontariff barriers, such as quotas and licenses – (no control on the activity of protected firms) • nationalised foreign firms and made large public investment – (inefficient management of public firms) – role of innovation and technological change IP in Africa: historical overview • In mid 1980s, the economic situation of most of African countries was very difficult. • Adoption of Structural Adjustment Programs (SAPs) [FMI, WB]. • The DS apparatus was eliminated and the ISI strategy abandoned • SAPs successful in: – liberalizing trade and the financial-sector, – favouring the privatization of public enterprises – inducing currency devaluations • SAPs not successful in favouring industrialization: – the industrial performance has been disappointing. Many African countries suffered de-industrialization process in the 1980s and 1990s IP in Africa: historical overview Assessment of the Structural Adjustment Programmes (SAPs) – SAPs did not promote significant improvements in technological capability, skill levels, productivity and export quality and greater value-added in the agro-industry sector (these were the expected responses from the reforms). – The weak African industrial structure is, at least in part a consequence of these interventions. – Several industrial sectors have still to recover from the SAPs period and, given the new international context, this task seems to be increasingly difficult The new world, the new rules and industrial policy in Africa today • The world economy is rapidly changing • New rules (WTO, REC, etc.) • New actors (China, India, etc.) • New products and new technological paradigms • Opportunities and challenges are different The new world, the new rules and industrial policy in Africa today • Industrialisation figures today among the highest policy priorities at the continental level: several initiatives, plans of action, development projects and call to develop industrialization in Africa. • African governments are still largely engaged in industrial policy. • A number of different industrial policy instruments are employed in African countries (next slide) Industrial Policy in Africa today What are the new IP options for African countries? New approaches to industrial policy – industrial clusters – upgrading along the agricultural value chain Industry in Africa: Industrial clusters • An emerging element in the African economic landscape is the industrial cluster. • Clusters are believed to play a significant role in the promotion and development of SMEs • The benefits of clustering are: 1. making market access easier 2. create labor pooling 3. facilitate technological spillovers 4. create an environment conductive to joint actions • The benefits of clusters would be particularly valuable to African SMEs given the difficult economic environment in which they operate. Industrial cluster: which policies? • Policies should be designed to create an environment conducive to the conditions under which a cluster can emerge. • The cluster approach works well when (at least) three actors take part into the initiative: the university, the government and the private sector. • While differentiated by cluster characteristics, IP should: – encourage acquisition, adaptation and diffusion of technology (science parks) – strengthen the education-business sector link – strengthen and upgrade skill training – provide physical infrastructure IP to upgrade along the agricultural value chain • Agriculture is crucial for African countries’ growth • Not all agricultural sectors provide the same opportunities for export-led growth. • Over the past quarter-century, there has been a significant transformation of global trade: away from traditional tropical products and towards non-traditional agricultural exports • There are a number of government projects and plans of action to support the agriculture sector in Africa. • NEPAD’s Comprehensive Africa Agriculture Development Programme (CAADP) • Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa (AGRA) • UN, World Bank, and IMF High Level Task Force on the Global Food Crisis IP to upgrade along the agricultural value chain • The new content: increasing importance of GVCs in agricultural trade – the role of standards – global buyers become more demanding • Governments should: – provide physical and informational infrastructure to support coordination between enterprises and traders – develop efficient marketing organizations – support the development of local consultancy and certification companies for standards – collaboration between export enterprises – provide business-oriented services to farmers Some remarks • African countries need to strengthen the processing activity to be able to compete at the world level and to induce a structural change of their economies • Historically, industrialization and structural change has been possible only through government intervention and IP • The world and the rules of the game have changed but there is still room for government intervention to favor industrialization • New tools and strategies are available: cluster approach and policies to up-grading along the agricultural value chains Industrial policy in BRICS IP in BRICS • We explore the history and the evolution of IP in BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa). • They are the new success stories • We try to answer to a number of difficult questions such as: 1. 2. 3. 4. What has been the role of IP in the BRICS countries’ development process? Which are the common elements and the main differences (if any) between the different IP models? Are the IP models converging towards a similar type of IP? Are there lessons that can be learnt from the BRICS industrialization experiences? Brazil The history of IP in Brazil (in one slide) • ISI strategy (since 1940s) • 1982 crisis (partially related to the ISI strategy) • Washington Consensus reform • Return of IP (since Lula Presidency, 2003) Main characteristics of the current approach to IP • Large involvement of the Government in supporting manufacturing • Creation of new agencies and institutions to manage IP • Attempt to improve the public-private dialogue (and cooperation with university) • Emphasis on technology and innovation policies Lessons from the Brazilian experience • IP may require a long-term perspective – especially if it targets high-tech sectors • This also implies that IP needs to adapt to the changing internal and external conditions: a given objective could be achieved through different specific measures China The history of IP in China in one slide • Industrialization through central economic planning (since the 1950s) • 1978 Economic reforms • Since mid 80s, adoption of an IP characterized by an evolving (creative) combination of different measures – State highly interventionist – Reduction and modification of the role of SOEs – Attraction of FDI (technology acquisition) Lessons from the Chinese experience • One of the reasons for China‘s economic success has been the ability to choose and adapt IP to the numerous changes that took place in its domestic development strategy and international conditions. This suggests that flexibility in the type and use of policies may be crucial to the effectiveness of the industrialization strategy. Lessons from the Chinese experience • The Chinese case is characterized by unique characteristics and several peculiarities. – Example. issues related to the regulation of coexistence of private firms and SOEs; the possibility to attract FDI because of the size of the domestic market, etc. This implies that extreme care is needed when it considered as a model to be replicated. India • ISI strategy (since independence) – strict regulation of industry – five years plans – State highly interventionist • 1991 Structural Reforms (drastic trade liberalization, deregulation of economic activity) • Since the 2000s, pragmatic approach to IP Lessons from the Indian experience 1. The recent high GDP growth has been achieved through not-orthodox policies. – This is not to deny the positive effect of the reforms. Though one should recall that the liberalization process has taken place at a controlled pace and that even after the reform several industrial policies remained in place. Lessons from the Indian experience 2. The Indian experience also tells us what IP should avoid: 1) controlling prices; 2) controlling quantity; 3) imposing the geographical location of economic activities. 3. The need and advantage (in terms of implementation ad support) of IP enjoying political and social acceptance. Russia IP since the end of URSS • Drastic economic reforms (liberalization, privatization and de-regulation) • Policies to attract FDI: various phases (increasingly more welcoming but with some halt) • Attempts to create a dialogue between the Government and the private secto Lessons from the Russian expericence • IP may take very different forms depending on the characteristics of the economy (e.g. reducing uncertainty in the economy) • Effective IP needs a continuous dialogue between the Government and the private sector: this requires the building of mutual trust, which is something very delicate and requires long time South Africa The history of IP in one slide • Two peculiarities – apartheid – the co-existence of the mineral-energy complex and manufacturing (conflict between the two) • ISI strategy (since the 1940s) • New industrial policy (since the democratic transition) Lessons from the South African experience • The activities and successes of the DTI (Department of Trade and Industry) and of the IDC (Industrial Development Corporation) clearly show the importance of developing government agencies’ capabilities to make IP effective • The way in which the IP has been presented to the public and conducted created a large support for that. Given the risk associated with IP (possible mistakes and failures) and the long-term horizon usually associated with it, it is crucial that there is a large support for IP. Some remarks • BRICS are not much different as for their (nonorthodox) approach to IP • BRICS countries are very different as for the specific measured of their IP • External elements (i.e. WTO) will probably contribute to force convergence in general IP design • Country experimentation will (probably) continue Historical evidence: some remarks • Necessary conditions (sector-level externalities or sectoral a latent comparative advantage) not easy to identify ex ante • There is no evidence that sectors which have been protected historically are those with such a latent comparative advantage and sector-level externalities. • Protection to declining not emerging sectors: an inherent bias against promoting sectors with a latent comparative advantage. Empirical evidence How to resolve the debate? Empirical evidence • Evidence on infant industry protection • It is the best known and most maligned type of IP • All countries in any time have used it: from England in the XVIII century to present day US (Boeing), Europe (Airbus), and China (cars). • Look at costs and benefits of intervention. – Mill test : protection allows sector to exploit learning effects and move down marginal cost curve – Bastable test: aggregate benefits outweigh costs to consumers Sectoral studies Evidence is mixed: getting interventions “right” is difficult 1. Industry-specific case studies – Yes, welfare increased due to intervention • Aircraft in Europe • Steel rail industry in the USA • Production of electricity from wind power – No, welfare fell as a consequence of intervention • Semi-conductors in Japan • Tinplate in the United States • Computers in Brazil 2. Cross-industry studies – Removal of protection often generates within-firm and within-industry productivity gains – But studies typically fail to measure the impact of policies, focusing instead on outcomes (like trade shares). What to conclude from this mixed evidence? • We know externalities exist but exploiting them is not easy • If agglomeration economies are important, then IP in small domestic markets is likely to fail • This means that: – Intervention should be oriented towards • sectors with a latent comparative advantage • sectors with large externalities or coordination failures Policy Implications for IP and Trade • Who is doing IP matters (need strong institutions to prevent capture) • What is being promoted makes a big difference: – sectors with strong externalities (learning by doing; spillovers to other sectors) – sectors with a “latent” comparative advantage • When to promote: emerging not declining sectors Warning: Agglomeration may be necessary but not sufficient for increased productivity. Subsidizing the software sector may not generate a Silicon Valley FDI attraction as IP • All countries promote incoming foreign investment, but this is rarely referred to as IP. • In 2010, 103 countries offered tax concessions to foreign companies setting up facilities within their borders. • Countries frequently offer also other benefits, such as free or subsidized infrastructure. FDI attraction as IP • Multinationals should be attracted to produce key inputs or to bring specific knowledge needed by clusters with the ability to absorb them. • Without host-country policies to develop local capabilities, MNC-led exports likely to remain technologically stagnant, leaving developing countries unable to progress beyond the assembly of imported components. • Countries should target specific sectors more than others, moving away from policy neutrality: promote FDI selecitvely • These are: telecommunications, vehicles and transport equipment, computers). The sectors where we expect there to be Marshallian externalities. Suggestions for effective IP • Don’t expect governments to identify coordination failures, but invite sector and cluster organizations to come forward • If such organizations are weak, provide support to sectors that want to initiate or improve their organizations • Public-private collaboration is crucial Outline 1. The importance of manufacturing for economic development 2. The return of Industrial Policy (IP) 3. What is IP? 4. Theoretical justification(s) for IP 5. Historical experiences 6. Empirical evidence (trade) – evidence on infant-industry protection – cross-country evidence on tariffs, trade, and growth – “soft” versus “hard” IP 7. A special case: innovation policy Innovation and innovation policy: what are they and why they are important Outline 1. Innovation: definition(s), actors, determinants 2. Why innovation is important 3. Measurement of innovation 4. Innovation policy Outline 1. Innovation: definition(s), actors, determinants 2. Why innovation is important 3. Measurement of innovation 4. Innovation policy Definition of Innovation • According to OECD, an innovation is the implementation of a new or significantly improved product (good or service), or process, a new marketing method, or a new organizational method in business practices, workplace organization or (even) external relations (OECD, 2005). • Innovation also includes social innovation, i.e. innovations that seek new answers to social problems. The actors of innovation • This definition clearly suggests that there are several economic actors engaged in innovation. • Among these, the most important are 1) private and public firms, 2) universities and public research institutes and 3) the government. • Universities and public research institutes play a crucial role by providing education, training, creation and diffusion of knowledge, • Government’s role is to support private initiatives through measures designed to favor innovation. The main characteristics of innovation • Innovation may be characterized by several dimensions including: 1. the type of innovation (product/ process innovation), 2. the degree of novelty of the innovation (incremental/radical innovation), 3. the source of innovation (technological/nontechnological innovation). (1) The type of innovation (product/ process innovation) • Product innovation is the introduction of a good or service that is new or has significantly improved characteristics or intended uses. • Process innovation refers to the implementation of a new or significantly improved production or delivery method. • Type of innovation firms perform varies significantly across countries, across firm size and economic sectors. • Firms often adopt mixed model of innovation. (2) The degree of novelty of the innovation (incremental/radical innovation) • A radical innovation is one that has a significant impact on a market and on the economic activity of firms in that market. • An incremental innovation concerns an existing product, service, process, organization or method whose performance is significantly enhanced or improved. • The dominant form of innovation is the incremental one. – Incremental innovation is also the more relevant form in the case of developing countries. (3) The source of innovation (technological/non-technological innovation). • Technological innovations are usually associated with product and process innovation. • Non-technological innovations are generally associated with organizational and marketing innovations. • In practice, technological and non-technological innovations are in fact highly interconnected. Other determinants of innovation • The nature of innovation greatly differs – from sector to sector – across countries – time periods Sectoral characteristics of innovation • The nature of innovation depends on the characteristics of the sector. – Some sectors are characterized by rapid change and radical innovations, others by smaller, incremental changes. – The source of innovation may significantly vary between sectors. • high-technology sectors: R&D plays a central role in innovation activities, while other sectors rely to a greater degree on the adoption of existing knowledge and technology. • Low-and medium-technology sectors: often characterized by incremental innovation and by foreign technology adoption. Social Innovation • No agreed definition of social innovation. • OECD (2010) defines social innovation as a tool to identify and respond to social challenges when the market and the public sector have failed to do so. – a form of economic innovation satisfying new needs not provided for by the market (even if markets may also intervene). • defined more by the nature and objectives of the innovation rather than by the characteristics of the changes themselves. • The non-profit sector plays a special role in fostering and implementing social innovation Outline 1. Innovation: definition(s), actors, determinants 2. Why innovation is important 3. Measurement of innovation 4. Innovation policy Why innovation is important • Innovation plays a key role in economic development by contributing to growth, jobs creation and helping address social and environmental challenges (OECD, 2005). • Innovation leads to improved competitiveness and is a major explanation of why growth rates at the firm, regional and national level differ Why innovation is important for developing countries • Innovation is important for developed countries • Sometimes still questioned for developing countries. • Innovation is often understood only as high technology. • Innovation takes place in all sectors, including services, agriculture and mining (OECD, 2010). • Different types of innovation play different roles at various developmental stages. – in earlier stages, incremental innovation is the most relevant form of innovation as it is associated with the adoption of foreign technology. – at later stages, high-technology and R&D-based innovation matter more. Three stages of technology acquisition • There are three main stages of technology acquisition within a developing economy: – first stage: the economy acquires mature foreign technologies (assembly operations); – second stage: consolidation of technology (duplicative imitation followed by, creative imitation; – final stage: domestic generation of new technologies. Stages of economic development and characteristics of innovation Country category Developing countries and emerging and countries Mainly emerging countries but also developing ones Mainly emerging countries Type/source of innovation Improve productivity and Incremental innovation process technology based on adoption of foreign innovations and technologies. Innovation needs to respond to specific “local” conditions for outcomes. Favour the generation of Incremental innovation inclusive innovation to based on combination of improve welfare and access foreign technology and/or to business opportunities. local, traditional knowledge. Build up innovation Incremental and radical capacities to reach the world innovation capacity to technological frontier compete with leading world innovators. Build-up niche competencies Incremental innovations based on applying foreign innovations and technologies strategically to support industrial development. Climb the value ladder in Incremental and radical global value chains innovation capacity to differentiate contributions Objective of innovation Keep competitiveness in frontier industries Innovation is identical to developed countries exposed to developments in the global market. Main agents involved Evidence/example Universities and research institutes, private businesses, especially those with exposure to foreign markets NGOs, small firms, public and private associations engaged in disseminating knowledge via networks New plant varieties for agriculture New methods for mineral extraction (Chilean copper industry) India (nano cars; grassroots innovation) Mobile banking services Private firms, Universities and research institutes, public institutions South Korea in the 1990s. Colombian and Ecuadorian flower industry Malaysia’s palm oil sector Public institutions to address co-ordination challenges, private sector initiative including foreign companies Private sectors with support from public agents, intermediaries, diasporas can play a central role, large firms can be important. Private sector in interaction with public research institutions and universities, role of large firms Automotive industries in Malaysia and Thailand India’s software industry Brazilian company Embraer Outline 1. Innovation: definition(s), actors, determinants 2. Why innovation is important 3. Measurement of innovation 4. Innovation policy The measurement of innovation Data on innovation • Innovation is a complex phenomenon • Its measurement is difficult: data and indicators • Several data can be used to measure innovation. 1) firm level data; 2) industry level data; 3) household-level data; 4) labour force survey; 5) R&D statistics; 6) innovation data; 7) patent data; 8) IPR data (trademarks, design rights and utility models); 9) scientific and technological output (citations, articles, etc.). Data collection: innovation survey • Innovation survey: a powerful and important instrument to increase knowledge about why and how innovation happens in firms • Innovation surveys collect information about: – – – – – innovation strategies, reasons for investing in innovation, how firm combine different types of innovation, quantitative data on sales from product innovations spending on a range of assets beyond R&D The measurement of innovation • All these data can be used and combined to construct quantitative indicators of innovation activities. • Examples of innovation indicators are the level and rate of growth of: – – – – – – – R&D expenditure (as % of GDP); number of researcher employed in R&D activities (country level); number of total patents (country level); school enrollment in tertiary education; number of articles in scientific and technical journals; high-tech export (as % of manufacturing export); ICT expenditure (as % of GDP). The measurement of innovation • Different types of innovations need different type of indicators. – indicators to measure the degree of product innovation are different from the ones used to measures the rate of process innovation. • IMPORTANT: traditional and most commonly used measures of innovation may not be able to capture the full richness of innovation activities in developing countries. The measurement of innovation in developing countries • Commonly used measures of innovation may not be able to capture the full richness of innovation activities in the Pacific region. • Innovation creation and knowledge diffusion may be have significantly different characteristics from those found elsewhere. • A different approach to the measurement of these activities needed. • To improve the understanding of the specific innovation process taking place in the local economies, we could use semi-structured interviews, ad-hoc questionnaires focus-groups Outline 1. Innovation: definition(s), actors, determinants 2. Why innovation is important 3. Measurement of innovation 4. Innovation policy Innovation policy Innovation policy: what is it, why we need it and what it is its content • Innovation is a heterogeneous phenomenon whose characteristics depends on various conditions at various levels (firm, industry, region, country, world). • At the firm level: innovation determinants include • • • • • • • level of R&D expenditure, the degree of sectoral innovation opportunities, the easiness to access finance, the availability of skilled workers, the market conditions (degree of competition, demand conditions, etc.) the regulation of intellectual property rights, the degree of knowledge spillovers and so on. Innovation policy: what is it, why we need it and what it is its content • One crucial elements determining the emergence, the development and the expansion of innovation activities is government intervention. – Governments in both developed and developing countries are increasingly making innovation a key issue on policy agendas, recognizing its potential to promote economic growth and address social and environmental challenges. • Interestingly, innovation policy is usually less controversial than other government policies. Innovation policy: what is it, why we need it and what it is its content • The basic argument for government support to innovation is that a market economy cannot generate the optimal levels of investment in innovation because of: 1. market failures; 2. partial appropriability due to spillovers; 3. information asymmetries • These market failures inhibit private firms from investing the optimal amount of resource (they underinvest) in innovation activities, thus depriving the economy from one of the key levers of sustained growth. • The role of government is thus to restore optimality by providing different forms of support to firms’ investment in innovation. Why the market cannot provide the optimal investment in innovation There are three main reasons: 1. market failures 2. only partial appropriability due to spillovers • firms investing in innovation risk that their discovery are copied by competitors that have not incurred in discovery costs 3. information asymmetries Innovation policy: what is it, why we need it and what it is its content • The notion of which measures should be used to sustain innovation has changed considerably over the past decades. • Nowadays, innovation policy can be defined as the (large) set of measures direct to induce, support and foster innovation at the local, firm, sectoral and national level. Innovation policy: what is it, why we need it and what it is its content • Innovation policy includes a number of different measures and instruments. • In particular, innovation policy includes technology policy and science policy. • There are several measures through which government support innovation: – – – – – tax exemptions for innovation investments subsided credit for innovative firms the creation of public research centers attraction of FDI public procurement Innovation policy in developing countries: main characteristics and future challenges • The literature on innovation policy in developing countries is limited • Often official documents by LDCs governments overlook the topic and do not include innovation policy among the priorities. • LDCs have peculiar elements (e.g. the role of traditional knowledge, its rich biodiversity, etc.) that need to be properly considered in the context of innovation policy Innovation policy in developing countries • There are several topics within the innovation domain that are extremely relevant for on which governments should focus more their efforts. • These are: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. renewable energy production, marine resources management, telecommunications and IT regulation and development, climate adaptation strategies, waste management, natural disaster mitigation sustainable land use What do we have learnt on innovation policy in developing countries The review of the international experiences also suggests that – successful innovation policy has been often the result of experiments of cooperation between the government and the private sector concerning the design and also the implementation of the different measures. In some other cases, entrepreneurial association has also taken the lead in making policy proposals (i.e. Colombia and Mexico) • example of a co-responsible attitude of government and private sector, which in the end are the beneficiaries of innovation policy. Innovation for sustainable development The importance of innovation for sustainable development • During the last decade, major global and regional changes in climate and the biosphere had serious implications for the sustainability of the ecosystems • Recently research centers in the region have started focusing on understanding better the co-evolution of the atmosphere, the weather, the ocean and the biological diversity. Example of benefit-sharing arrangements for indigenous and traditional knowledge. The development of an anti-HIV compound through traditional methods: Traditional healers in the Falealupo village of Samoa have for centuries used a tea made by steeping ground-up stems from the mamala tree to treat yellow fever virus and hepatitis. The Samoan healers introduced Western research scientists to the plant’s healing capacity. The National Institutes of Health and the AIDS Research Alliance used the plant to isolate a compound called prostratin, which is thought to have high potential as an HIV retroviral. In 2004, the University of California at Berkeley and the Samoan government signed an agreement allowing the university’s researchers to use the mamala tree to develop an anti-AIDS drug. The university will share any royalties from the sale of a gene-derived drug with the people of Samoa. [World Bank, 2010] Example of benefit-sharing arrangements for indigenous and traditional knowledge • This example is important because it illustrates – the economic and social characteristics that are peculiar to developing countries – how different may be the analysis of innovation in these contexts – more research is needed to fill the knowledge gap about the opportunities for innovation, the mechanisms behind innovation in the region and which type of measures and interventions can favour innovation. Future research • More research is needed concerning both innovation and innovation policy in developing countries • Knowledge gaps that have to be filled in order to create the conditions for fostering innovation and inducing sustainable long-term economic development. Future research There is the need to better understand the factors, the mechanisms and the obstacles that characterize innovation processes in developing countries – more information about the current domestic innovation capabilities and the type and number of innovation actives already conducted by domestic firms and public institutions. – more effort should be put to have a better understanding of the possible future opportunities for innovation in the region. – possible role that scientific and technological cooperation would perform in the generation of new products and processes and of novel forms of collective organization. Future research • A better understanding of the national and regional innovation systems • There are three aspects on which future research should focus: 1. to identify the country-specific characteristics of the different national innovation systems 2. to map the innovation capabilities and opportunities 3. identifying ‘niches’ for innovation as to understand what should be improved and in which direction to intervene Some final remarks • Manufacturing is crucial to economic development • Industrial policy is an important instrument to support the industrialization process • IP is very complex and dangerous tool • Theory says that IP is needed in several situations • Historical experiences shows that the effects of IP have been (often) very disappointing • It is not anymore IF, it a matter of HOW to do IP References • Di Maio, M. (2014). Industrial Policy in BRICS Countries: Similarities, Differences and Future Challenges. In: Structural Change, Industrialisation and Poverty Reduction in the BRICS, edited by Naudé, N., Szirmai, A. and N. Haraguchi. Chapter 17. Oxford: Oxford University Press • Di Maio, M. (2014). Industrial Policy. In: International Development: Ideas, Experience, and Prospects, edited by Currie-Alder, B., R. Kanbur, D. Malone and R. Medhora. Chapter 32. Oxford: Oxford University Press • Di Maio, M. (2009). Industrial Policies in Developing Countries. History and Perspectives. In: The Political Economy of Capabilities Accumulation: the Past and Future of Policies for Industrial Development, edited by Cimoli, M., Dosi G. and Stiglitz, J. E., Ch.5. Oxford University Press • Harrison, A. and Rodríguez-Clare, A. (2010). Trade, Foreign Investment, and Industrial Policy for Developing Countries*, In: Dani Rodrik and Mark Rosenzweig, Editor(s), Handbook of Development Economics, Elsevier, Volume 5, Chapter 63 , Pages 4039-4214 • UNECA (2012). Industrial Policies for the Structural Transformation of African Economies: Options and Best Practices How to contact me Michele Di Maio Department of Business and Economic Studies University of Naples “Parthenope” E-mail: michele.dimaio@uniparthenope.it Webpage: https://sites.google.com/site/micdimaio/micheledimaio