File

advertisement

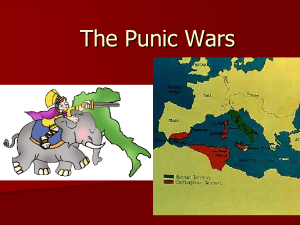

TITUS LIVIUS: LIBRI AB URBE CONDITA Livy, or more properly Titus Livius (59 B.C. – 17 A.D.) was born in Padua (modern Padova) situated between the modern cities of Verona and Venice in the Po Valley, which was then known as Cisalpine Gaul (i.e `Gaul on this side of the Alps’). He was said never to have lost his local accent. Livy was born in the first consulship of Julius Caesar (left) and belonged to the same generation as Caesars nephew, Augustus (right), Rome’s first emperor. The emphasis in Ab Urbe Condita on traditional Roman virtues fitted in with Augustus’s moral reform programme, but Livy was not so closely associated with the emperor as Virgil. After the publication (perhaps in 5 A.D) of Livy’s account of the civil wars that ended the republic, Augustus joked that the historian was a `Pompeian’, i.e a supporter of the general who had fought against Julius Caesar in 49-48 B.C. Of the 142 books that made up Livy’s mammoth Ab Urbe Condita (`From the Foundation of the City’), only 1-10 (covering the period 753 – 295 B.C.) and 20-35 (on 218 – 167 B.C.) have survived. The picture shows a modern edition of Books 1-5, which would have been five separate papyrus scrolls when first published. Although most of his work has been lost, we still have the ancient summaries (`Periochae’) of all the books and the Latin text of these, with Jona Lendering’s English translation, is available on the livius.org site. Initium Libri I Ab Urbe Condita : iam primum omnium satis constat Troia capta in ceteros saevitum esse Troianos, duobus, Aeneae Antenorique, et vetusti iure hospitii et quia pacis reddendaeque Helenae semper auctores fuerant, omne ius belli Achiuos abstinuisse. The opening of Book I of `From the Founding of the City’: First of all, there is general agreement that after the capture of Troy the Greeks behaved savagely towards the other Trojans but did not exercise the rights of war against two of them, Aeneas and Antenor, both because of old ties of hospitality and because they had always been advocates of peace and of returning Helen. Though his preface makes clear that he is aware that legends are not authentic history, Livy starts Book 1 with the legend of Aeneas. What he presents as the generally accepted version is very different from the one given by Virgil, even though both men probably produced their accounts in the early 20s B.C. `Hannibal at the Summit of the Alps’ is an extract (chapters 35-37) from Book 21 which describes the beginning in 218 of the Second Punic War (218 – 202 B.C.) `Punicus’ was the adjective used by the Romans for language and culture of Carthage, a city in North Africa founded by Phoenician colonists. Choosing to attack over the mountains because the Romans would not expect an attack from that direction, Hannibal had to contend with hostile tribes on the ascent and then with steeper slopes, snow and ice on the way down. Hannibal’s exact route is unknown but it must have been over one of the passes shown on this map of the western Alps. A summer photograph of the route over the Col du Clapier which Pat Hunt believes Hannibal took. His theory is explained at: http://news.stanford.edu/news/2007/may16/hannibal-051607.html The Col du Montgnèvre, the route argued for by Jona Lendering at http://www.livius.org/ha-hd/hannibal/alps.html Rome and Carthage had already clashed in the First Punic War (264 to 241B.C.), caused by a dispute over control of Sicily when Rome was already the dominant power in Italy and Carthage’s empire included a large area of North Africa, south-eastern Spain, Corsica and Sardinia. For a full account, see http://www.thelatinlibrary.com/imperialism/notes/punicwars.html Defeated in the first conflict, the Carthaginians lost not only Sicily but also Sardinia and Corsica. To compensate, they sought to extend their Spanish empire and Hamilcar, the general who led the Carthage’s forces in Spain, is said to have made his young son, Hannibal, swear undying enmity towards Rome. Hannibal succeeded to his father’s position in Spain and Rome declared war again in 218 B.C., after Carthage refused to halt an offensive against Saguntum, a Spanish city Rome had accepted as an ally. After crossing the Alps, Hannibal inflicted several crushing defeats on Roman armies, but was unable either to put Rome itself under siege or to win over her north Italian allies. He was finally recalled to Africa when a Roman force under Publius Cornelius Scipio threatened Carthage itself. Scipio won the war for Rome by defeating Hannibal in one of the most decisive battles of Western history at Zama in 202 B.C, Rome thus became master of the western Mediterranean just a few years after Qin Shi Huang (秦始皇), on the other side of Eurasia, made himself master of China.