Week 7

advertisement

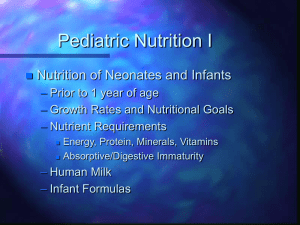

Infancy 2002 • Growth in infancy • Physiology of infancy • GI • Renal • • • • • Development of feeding skills Nutrient requirements Infant formulas Non milk feedings/solids Oral health GROWTH IN FIRST 12 MONTHS • From birth to 1 year of age, normal human infants triple their weight and increase their length by 50%. • Growth in the first 4 months of life is the fastest of the whole lifespan - birthweight usually doubles by 4 months • 4-8 months is a time of transition to slower growth • By 8 months growth patterns more like those of 2 year old than those of newborn. Weight Gain in Grams per Day in One Month Increments - Girls Age Up to 1 month 1-2 months 2-3 months 4-5 months 5-6 months 10th percentile 16 50th percentile 26 90th percentile 36 20 29 39 14 23 32 13 16 20 11 14 18 Guo et al., J Peds. 1991 Weight Gain in Grams per Day in One Month Increments - Boys Age Up to 1 month 1-2 months 2-3 months 3-4 months 4-5 months 5-6 months 10th percentile 18 50th percentile 30 90th percentile 42 25 35 46 18 26 36 16 20 24 14 17 21 12 15 19 Guo et al., J Peds. 1991 Energy & Protein • Young infant requires substantial percentage of energy intake for growth • Relatively large percentage of requirement for protein in young infant is accounted for by protein accretion Body increment gained, g/day Energy Used for Growth Body Energy Used for Increment g/d Growth Age in Protein mos. Fat Kcal/d Kcal/kg/d 0-4 3.12 10.35 153.6 28.4 4-6 2.0 4.8 78.6 10.4 6 - 12 1.9 1.4 40.6 4.5 Body Composition • BMI and percentage of body weight made up of fat increase rapidly during the first months of life – Fat accounts for 0.5% of body weight at the fifth month of fetal growth and 16% at term. – After birth, fat accumulates rapidly until approximately 9 months of age Individual Growth Patterns – Weight and length at term appear to be primarily determined by nongenetic maternal factors – Birth weigh and birth length weakly correlate with subsequent weight and length values Individual Growth Patterns, cont. • Extremes of birth weight and length tend to regress to the mean, and genetic factors appear to have a stronger effect by the middle of the first year. • infants who are born small but are genetically destined to be longer may shift percentiles on growth grids during the first 3 to 6 months • larger infants at birth whose genotypes are for smaller size tend to grow at their fetal rates for several months before the lag-down in growth becomes evident Individual Growth Patterns, cont. – African American males and females are smaller than Caucasians at birth, but they grow more rapidly during the first 2 years – Patterns of growth in breastfed infants may be different from formula fed infants Assessment of Growth • Growth Charts – http://www.cdc.gov/growthcharts/ • Growth Velocity New Growth Charts • Data from old charts came from private study of primarily Caucasian, formulafed, middle-class infants from southwestern Ohio • New charts have data from NHANES and use more sophisticated smoothing techniques • 16 new charts provided by gender and age New Growth Charts • Clinical charts for infancy for girls and boys: – weight – length – weight for length – OFC • Choice between outer limits at 3rd and 97th or 5th and 95th percentiles Physiology - GI Maturation Genetic Endowment Biological Clock Gut Development Environmental Influences Regulatory Mechanisms In utero • fetal GI tract is exposed to constant passage of fluid that contains a range of physiologically active factors: – growth factors – hormones – enzymes – immunoglobulins • these play a role in mucosal differentiation and GI development as well as development of swallowing and intestinal motility At Birth • gut of the newborn is faced with the formidable task of passing, digesting, and absorbing large quantities of intermittent boluses of milk • comparable feeds per body weight for adults would be 15 to 20 L Enteral Feeding Requirements – Coordinated sucking and swallowing – Gastric emptying – Intestinal motility – Secretions: salivary, gastric, pancreatic, hepatobiliary – Enterocyte function in terms of enzyme synthesis, absorption, mucosal protection – Metabolism of products of digestion and absorption – Expulsion of undigested waste products Human Milk • complements Immaturities of these systems as well as their maturation – Epithelial growth factors and hormones – Digestive enzymes - lipases and amylase Motility - Upper GI • Esophageal motility is decreased in the newborn • LES is primarily above the diaphragm • LES pressure is less for first months • Gastric Emptying may be delayed Motility - Intestinal • Intestinal motility is more disorganized • Prolonged transit time in upper intestines may improve absorption of nutrients • Rapid emptying of ileum and colon may reduce time for water and electrolyte absorption and increase risk of dehydration Stooling • Gasrtro-colonic reflex is active in the neonate: entry of food into beginning of small intestine causes reflexive propulsion toward the rectum • Passage of stool occurs within 24 hours for most healthy full term infants. • Meconium is passed for the first 2 or 3 days Stooling, cont. • In first week of life may pass as many as 9 stools per day, declines to 3 or 4 by second week • Later breast fed babies may not even have daily stools. • Fetal gut is sterile, but infant exposed to microorganisms during birth. • Bacteria may be detected in meconium within 4 hours of birth following vaginal birth Common GI Symptoms Common GI Symptoms & Infant Stools Effect of infant formula on stool characteristics of young infants. Pediatrics 1995 Jan;95(1):50-4 • 238 healthy 1-month-old infant were fed one of four commercial formula preparations (Enfamil, Enfamil with Iron, ProSobee, and Nutramigen) for 12 to 14 days in a prospective double-blinded (parent/physician) fashion. Parents completed a daily diary of stool characteristics as well as severity of spitting, gas, and crying for the last 7 days of the study period. A breast-fed infant group was studied as well. Gut Hormones • Gastrointestinal peptides are found in venous cord blood at birth in levels similar to those of fasting adults • In fetal distress a number of gut peptides are elevated which might account for passage of meconium • With enteral feeding levels of gut hormones (motilin, neurotensin, GIP (gastric inhibitory peptide), gastrin, enteroglucagon, PP pancreatic polypeptide, rise rapidly Possible Roles for Gut Hormones in Early Infancy Motilin Enteroglucagon Enteroglucagon, gastrin, pancreatic polypeptides Gastric Inhibitory polypeptide (GIP) Increased gut motility Tropic to gut mucosa Intestinal mucosal and pancreatic growth Stimulus to insulin release Gut Hormones Influenced By: • Choice of breast or formula feeds • Enteric intake (induces epithelia hyperplasia and stimulates production of microvillous enzymes) • Early enteral feeding (enteral feeding is strongly encouraged to promote GI function and differentiation) Programming by Early Diet • Nutrient composition in early diet may have long term effects on GI function and metabolism • Animal models show that glucose and amino acid transport activities are programmed by composition of early diet • Animals weaned onto high CHO diet have higher rates of glucose absorption as adults compared to those weaned on high protein diet Pancreas • Pancreatic function is relatively deficient at birth and mature levels of pancreatic enzymes are not achieved until late infancy • Pancreatic amylase activity increases after 4 to 6 months Lipase levels do not approach adult efficiency until about 6 months Protein Digestion Factor In Early Infancy Compared to Adult levels Gastric Acid Trypsin Chymotrypsin Pancreatic Proteases Intestinal Mucosal peptidases Lower production Activity reduced Low levels Low levels Adequate Fat Digestion Factor In Early Infancy Compensating Compared to Mechanisms Adult levels Pancreatic Lipase Bile Acids Very low levels Low levels Lingual, gastric and breastmilk bile salt stimulated lipase Carbohydrate Digestion Factor In Early Infancy Compared to Adult levels Salivary Amylase Lower levels Pancreatic amylase Disacharidases Compensating Mechanisms Stays active in stomach Very low levels Breastmilk amylase Adequate levels Fermentation and absorption in large intestine Maturation in First Year • LES tone increases after 6 months and is associated with less reflux in most infants • Gastric acid and pepsin activity do not reach adult levels until 2 years • Pancreatic amylase increases by 6 months Retention of lactase activity is typical until 3 to 5 years. • Fat absorption does not approach adult efficiency until about 6 months • Lipase reaches adult levels by 2 years. Renal • Limited ability to concentrate urine in first year due to immaturities of nephron and pituitary • Potential Renal solute load determined by nitrogenous end products of protein metabolism, sodium, potassium, phosphorus, and chloride. Potential Renal Solute Load Feeding Human Milk Milk based formula Isolated Soy protein based formula Evaporated milk formula Whole cow milk Potential Renal Solute Load, mOsm/liter 93 135 165 260 308 Urine Concentrations • Most normal adults are able to achieve urine concentrations of 1300 to 1400 mOsm/l • Healthy newborns may be able to concentrate to 900-1100 mOsm/l, but isotonic urine of 280-310 mOsm/l is the goal • In most cases this is not a concern, but may become one if infant has fever, high environmental temperatures, or diarrhea Water Needs • Water requirement is determined by: – water loss • evaporation through the skin and respiratory tract (insensible water loss) • perspiration when the environmental temperature is elevated • elimination in urine and feces. – water required for growth – solutes derived from the diet Water, cont. • Water lost by evaporation in infancy and early childhood accounts for more than 60% of that needed to maintain homeostasis, as compared to 40% to 50% • NAS recommends 1.5 ml water per kcal in infancy. Water Needs Age Amount of Water (ml/kg/day) 3 days 80-100 10 days 125-150 3 mo. 140-160 6 mo. 130-155 9 mo. 125-145 1 yr. 120-135 2 yr. 115-125 Development of Infant Feeding Skills • Birth – tongue is disproportionately large in comparison with the lower jaw: fills the oral cavity – lower jaw is moved back relative to the upper jaw, which protrudes over the lower by approximately 2 mm. – tongue tip lies between the upper and lower jaws. – "fat pad" in each of the cheeks: serves as. It is thought that these pads serve as a prop for the muscles in the cheek, maintaining rigidity of the cheeks during suckling. – Feeding pattern described as “suckling” Developmental Changes • Oral cavity enlarges and tongue fills up less • Tongue grows differentially at the tip and attains motility in the larger oral cavity. • Elongated tongue can be protruded to receive and pass solids between the gum pads and erupting teeth for mastication. • Mature feeding is characterized by separate movements of the lip, tongue, and gum pads or teeth Feeding behavior of infants Gessell A, Ilg FL Age 1-3 months Reflexes Rooting and suck and swallow reflexes are present at birth 4-6 months Rooting reflex fades Bite reflex fades 7-9 months 10-12 months Oral, Fine, Gross Motor Development Head control is poor Secures milk with suckling pattern, the tongue projecting during a swallow By the end of the third month, head control is developed Changes from a suckling pattern to a mature suck with liquids Sucking strength increases Munching pattern begins Grasps with a palmer grasp Grasps, brings objects to mouth and bites them Gag reflex is less Munching movements begin when solid foods are eaten strong as chewing Rotary chewing begins of solids begins Sits alone and normal gag is Has power of voluntary release and resecural developing Holds bottle alone Choking reflex Develops an inferior pincer grasp can be inhibited Bites nipples, spoons, and crunchy foods Grasps bottle and foods and brings them to the mouth Can drink from a cup that is held Tongue is used to lick food morsels off the lower lip Finger feeds with a refined pincer grasp Feeding Interactions Age Infant Development Optimal Caregiver Behaviors Recognize and respond to infant cues, lets infant set tempo, talks and smiles 0-2 months Homeostasis Regulation of state, cycles of feeding and sleep, begins to interact 2-6 months Attachment Infant initiates and responds to social overtures Responds to infant, increased skills at reading cues, avoids interupting feedings 6-9 months Behavioral organization control, differentiation between cause and effect, beginning of autonomy Gives opportunities to explore, make messes, provides structure & let's infant decide how fast and how much to eat. Feeding Interactions, cont. Age 9-12 months 13-18 months Infant Development Optimal Caregiver Behaviors Consistently responds Recognizes boundaries to parent's gestures between playing and eating Organizes patterns Does not bribe, coax, beg teases, jokes and or force child to eat provokes Energy Requirements • Higher than at any other time per unit of body weight • Highest in first month and then declines • High variability - SD in first months is about 15 kcal/kg/d • Breastfed infants many have slighly lower energy needs • RDA represents average for each half of first year Energy Requirements, cont. • RDA represents additional 5% over actual needs and is likely to be above what most infants need. • Energy expended for growth declines from approximately 32.8% of intake during the first 4 months to 7.4% of intake from 4 to 12 months Mean Daily Energy and Protein Intakes Intake Energy Kcal Kcal/Kg Protein g g/kg Infant Adult 464 116 2500 36 10.4 2.6 93.8 1.3 Mean Daily Energy and Protein Intakes Intake Energy Kcal Kcal/Kg Protein g g/kg Infant Adult 464 116 2500 36 10.4 2.6 93.8 1.3 Energy Intakes by Breastfed and Formula Fed Boys (kcal/kg) Age in Mos. 1 2 3 5 6 Breastfed 115 104 95 89 86 Formula 120 106 95 95 92 1989 RDA: Energy and Protein Age in Months 0–6 6 - 12 Reference Weight (kg) 6 9 Energy Protein (kcal/kg/day) (g/kg/day) 108 2.2 98 1.6 From National Academy of Sciences: Recommended dietary allowances, Ed 10, Washington, DC, 1989, National Academy Press. 2002 Energy DRI 2002 Protein DRI 2002 Carbohydrate DRI 2002 Fat DRI Distribution of Kcals Breastmilk Formula % Protein 6 9 % Fat 52 48 % Carbohydrate 42 42 Protein • Increases in body protein are estimated to average about 3.5 g/day for the first 4 months, and 3.1 g/day for the next 8 months. • The body content of protein increases from about 11.0% to 15.0% over the first year Essential Fatty Acids • The American Academy of Pediatrics and the Food and Drug Administration specify that infant formula should contain at least 300 mg of linoleate per 100 kilocalories or 2.7% of total kilocalories as linoleate. LCPUFA: Background n-6 n-3 18:2 Linoleic 18:3 Linolenic 18:3 linolenic 20:5 EPA 20:4 Arachidonic 22:6 DHA LCPUFA: Background • Ability to synthesize 20 C FA from 18 C FA is limited. • n-3 and n-6 fatty acids compete for enzymes required for elongation and desaturation • Human milk reflects maternal diet, provides AA, EPA and DHA • n-3 important for neurodevelopment, high levels of DHA in neurological tissues • n-6 associated with growth & skin integrity Formula supplementation with long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids: are there developmental benefits? Scott et al. Pediatrics, Nov. 1998. • RCT, 274 healthy full term infants • Three groups: – standard formula – standard formula with DHA (from fish oil) – formula with DHA and AA (from egg) • Comparison group of BF Outcomes at 12 and 14 months • No significant differences in Bayley, Mental or Psychomotor Development Index • Differences in vocabulary comprehension across all categories and between formula groups for vocabulary production. Outcomes at 12 and 14 months • No significant differences in Bayley, Mental or Psychomotor Development Index • Differences in vocabulary comprehension across all categories and between formula groups for vocabulary production. Bayley Scales at 12 months Human Std. AA + Milk Formula DHA DHA MDI 108 105 105 104 PDI 100 105 98 101 MacArthur Communicative Development Inventories at 14 Months of Age Human Std AA + Milk formula DHA DHA Vocabulary Comprehension 101 100 98 92 Vocabulary production 97 101 99 91 Conclusion “We believe that additional research should be undertaken before the introduction of these supplements into standard infant formulas.” PUFA Status and Neurodevelopment: A summary and critical analysis of the literature (Carlson and Neuringer, Lipids, 1999) • In animal studies use deficient diets through generations - effects on newborn development may be through mothering abilities. • Behaviors of n-3 fatty acid deficient monkeys: higher frequency of stereotyped behavior, locomotor activity and behavioral reactivity Vitamins and Minerals • Need for minerals and vitamins increased per kg compared to adults: – growth rates – mineralization of bone & increases in bone length – Increased blood volume – energy, protein, and fat intakes Vitamins and Minerals • Focus on nutrients with controversies and/or recent research: – Vitamin K – Vitamin D – Iron – Fluoride Vitamin K: AAP, 1993 • Vitamin K deficiency may cause unexpected bleeding (0.25% to 1.7% incidence) during the first week of life in previously healthy-appearing neonates Vitamin K: AAP • Late HDN, a syndrome defined as unexpected bleeding due to severe vitamin K deficiency in infants aged 2 to 12 weeks, occurs primarily in exclusively breast-fed infants who have received no or inadequate neonatal vitamin K prophylaxis.. The rate of late HDN ranges from 4.4 to 7.2 per 100 000 births based on reports from Europe and Asia. When a single dose of oral vitamin K has been used as neonatal prophylaxis, the rate has decreased to 1.4 to 6.4 per 100 000 births AAP Recommendations • 1. Vitamin K1 should be given to all newborns as a single, intramuscular dose of 0.5 to 1 mg. • 2. Further research on the efficacy, safety, and bioavailability of oral formulations of vitamin K is warranted. AAP Recommendations • 3. An oral dosage form is not currently available in the United States but ought to be developed and licensed. If an appropriate oral form is developed and licensed in the United States, it should be given at birth (2.0 mg) and should be administered again at 1 to 2 weeks and at 4 weeks of age to breast-fed infants. If diarrhea occurs in an exclusively breast-fed infant, the dose should be repeated. AAP Recommendations • 4. The conflicting data of Golding et al and Draper and Stiller and the data from the United States suggest that additional cohort studies are unlikely to be helpful. Cochran Protocol: Vitamin K for preventing haemorrhagic disease in newborn infants • Vitamin K deficiency can cause bleeding in an infant in the first weeks of life. This is known as Haemorrhagic Disease of the Newborn (HDN) or Vitamin K Deficiency Bleeding (VKDB). Cochran Protocol: Vitamin K for preventing haemorrhagic disease in newborn infants • HDN is divided into three categories: early, classic and late HDN. Early HDN occurs within 24 hours post partum and falls outside the scope of this review. • Classic HDN occurs on days 1-7. Common bleeding sites are gastrointestinal, cutaneous, nasal and from a circumcision. Late HDN occurs from week 2-12. • The most common bleeding sites in this latter condition are intracranial, cutaneous, and gastrointestinal (Hathaway 1987 and von Kries 1993). Cochran Protocol: Vitamin K for preventing haemorrhagic disease in newborn infants • Vitamin K is necessary for the synthesis of coagulation factors II (prothrombin), VII, IX and X in the liver. • In the absence of vitamin K the liver will synthesize inactive precursor proteins, known as PIVKA’s (proteins induced by the absence of vitamin K). • HDN is caused by low plasma levels of the vitamin Kdependent clotting factors. In the newborn the plasma concentrations of these factors are normally 30-60% of those of adults. They gradually reach adult values by six weeks of age Cochran Protocol: Vitamin K for preventing haemorrhagic disease in newborn infants • The risk of developing vitamin K deficiency is higher for the breastfed infant because breast milk contains lower amounts of vitamin K than formula milk or cow's milk Cochran Protocol: Vitamin K for preventing haemorrhagic disease in newborn infants • In different parts of the world, different methods of vitamin K prophylaxis are practiced. Cochran Protocol: Vitamin K for preventing haemorrhagic disease in newborn infants • Oral Doses: • The main disadvantages are that the absorption is not certain and can be adversely affected by vomiting or regurgitation. If multiple doses are prescribed the compliance can be a problem Cochran Protocol: Vitamin K for preventing haemorrhagic disease in newborn infants • I.M. prophylaxis is more invasive than oral prophylaxis and can cause a muscular haematoma. Since Golding et al reported an increased risk of developing childhood cancer after parenteral vitamin K prophylaxis (Golding 1990 and 1992) this has been a reason for concern . Brousson and Klien, Controversies surrounding the administration of vitamin K to newborns; a review. CMAJ. 154(3):307-315, February 1, 1996. • Study selection: Six controlled trials met the selection criteria: a minimum 4-week follow-up period, a minimum of 60 subjects and a comparison of oral and intramuscular administration or of regimens of single and multiple doses taken orally. All retrospective case reviews were evaluated. Because of its thoroughness, the authors selected a meta-analysis of almost all cases involving patients more than 7 days old published from 1967 to 1992. Only five studies that concerned safety were found, and all of these were reviewed Brousson and Klien, Controversies surrounding the administration of vitamin K to newborns; a review. CMAJ. 154(3):307-315, February 1, 1996. • Data synthesis: Vitamin K (1 mg, administered intramuscularly) is currently the most effective method of preventing HDNB. The previously reported relation between intramuscular administration of vitamin K and childhood cancer has not been substantiated. An oral regimen (three doses of 1 to 2 mg, the first given at the first feeding, the second at 2 to 4 weeks and the third at 8 weeks) may be an acceptable alternative but needs further testing in largeclinical trials. Brousson and Klien, Controversies surrounding the administration of vitamin K to newborns; a review. CMAJ. 154(3):307-315, February 1, 1996 • Conclusion: There is no compelling evidence to alter the current practice of administering vitamin K intramuscularly to newborns. Vitamin D • Vitamin D requirements are dependent on the amount of exposure to sunlight. • Rickets has been reported in some high risk U.S. infants with dark skin • American Academy of Pediatrics recommends supplements of 10 mg (400 IU) per day for breastfed infants. Vitamin D, cont. • Pediatric Nutrition Handbook states that for white infants adequate exposure to sunlight to produce vitamin D is 30 minutes per week clothed only in a diaper, or 2 hours per week fully clothed with no hat. These exposures are mediated by time of year as well as latitude. Iron Fortification of Infant Formulas Pediatrics, July 1999 v104 i1 p119 • During the first 4 postnatal months, excess fetal red blood cells break down and the infant retains the iron. This iron is used, along with dietary iron, to support the expansion of the red blood cell mass as the infant grows. The estimated iron requirement of the term infant to meet this demand and maintain adequate stores is 1 mg/kg per day. • Infants born prematurely and those born to poorly controlled diabetic mothers are at higher risk of iron deficiency Iron Absorption In Percent Reported Absorbed Human Milk 48% Human Milk – in 21% 5 to 7 month olds who are also eating solid foods. Iron Fortified 6.7% Cow’s milk based Formula Infant Cereals 4 to 5% Infancy Study Hallberg et al Abrams et al Hurrel et al Fomon et al Iron • Iron absorption from soy formulas is less • Also consider: gastrointestinal bleeding associated with exposure to cow milk protein or infectious agents Iron Fortification of Formula • “The increased use of iron-fortified infant formulas from the early 1970s to the late 1980s has been a major public health policy success. During the early 1970s, formulas were fortified with 10 mg/L to 12 mg/L of iron in contrast with nonfortified formulas that contained less than 2 mg/L of iron. The rate of iron-deficiency anemia dropped dramatically during that time from more than 20% to less than 3%.” Iron Fortified Formula: Iron Deficiency • 9-30% of current US sales are low-iron formulas • Iron deficiency leads to reduction of iron-containing cellular protein before it can be detected as iron deficiency anemia by hct or hgb • Permanent effects of Fe deficiency on cognitive function are of special concern. Iron in Formula • Infant formulas have been classified as low-iron or iron-fortified based on whether they contain less or more than 6.7 mg/L of iron. – Current mean content of low iron formula is 1.1 to 1.5 mg/L of iron and high iron is 10 to 12 mg/L. – One company recently increased to 4.5 for low iron. – European formulas are 4-7 mg/l – Foman found same levels of iron deficiency at 8 and 12 mg/l Iron Deficiency Prevalence at 9 Months 1.1 mg iron per L plus supplemental foods 12-15 mg iron per L 28-38% 0.6% Iron Deficiency in Breastfeeding • At 4 to 5 months prevalence of low iron stores in exclusively breastfed infants is 6 - 20%. • A higher rate (20%-30%) of iron deficiency has been reported in breastfed infants who were not exclusively breastfed • The effect of iron obtained from formula or beikost supplementation on the iron status of the breastfed infant remains largely unknown and needs further study. GI Effects Attributable to Iron • Double blind RTC have not found effects. • Most providers know that, but parents often want to change to low iron….. • “yet it may remain temptingly easier to prescribe a low-iron formula, achieve a placebo effect, and ignore the more insidious long-term consequences of iron deficiency.” AAP Iron Recommendations 1. In the absence of underlying medical factors (which are rare), human milk is the preferred feeding for all infants. 2. Infants who are not breastfed or are partially breastfed should receive an iron-fortified formula (containing between 4.0-12 mg/L of iron) from birth to 12 months. Ideally, iron fortification of formulas should be standardized based on long-term studies that better define iron needs in this range AAP Iron Recommendations 3. The manufacture of formulas with iron concentrations less than 4.0 mg/L should be discontinued. If these formulas continue to be made, low-iron formulas should be prominently labeled as potentially nutritionally inadequate with a warning specifying the risk of iron deficiency. These formulas should not be used to treat colic, constipation, cramps, or gastroesophageal reflux. AAP Iron Recommendations 4. If low-iron formula continues to be manufactured, iron-fortified formulas should have the term "with iron" removed from the front label. Iron content information should be included in a manner similar to all other nutrients on the package label. AAP Iron Recommendations • Parents and health care clinicians should be educated about the role of iron in infant growth and cognitive development, as well as the lack of data about negative side effects of iron and current fortification levels. Foman on Iron - 1998 • Proposes that breastfed infants should have supplemental iron (7 mg elemental) starting at 2 weeks. • Rational: – some exclusively breastfed infants will have low iron stores or iron deficiency anemia – Iron content of breastmilk falls over time – animal models indicate that deficits due to Fe deficiency in infants may not be recovered when deficiency is corrected. Fluoride • Fluoride Recommendations were changed in 1994 due to concern about fluorosis. • Breast milk has a very low fluoride content. • Fluoride content of commercial formulas has been reduced to about 0.2 to 0.3 mg per liter to reflect concern about fluorosis. • Formulas mixed with water will reflect the fluoride content of the water supply. Fluorosis is likely to develop with intakes of 0.1 mg/kg or more. Fluoride, cont. • Fluoride adequacy should be assessed when infants are 6 months old. • Dietary fluoride supplements are recommended for those infants who have low fluoride intakes. Fluoride Supplementation Schedule Age Fluoride Concentration in Local Water Supply, ppm < 0.3 0.3-0.6 >0.6 6 mo. to 3 y 0.25 0.00 0.00 3-6 y 0.50 0.25 0.00 6 y to at 1.00 0.50 0.00 least 16 y American Dental Association, American Academy of Pediatrics, American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry, 1994. AAP: Breastfeeding and the Use of Human Milk, 1997 • Formal evaluation of breastfeeding by trained observers at 24-48 hours and again at 48 to 72 hours. • No supplements should be given unless a medical indication exists. • When discharged at <48 hours, should have FU visit at 2 to 4 days of age, assessment at 5 to 7 days, and be seen at one month. AAP: Breastfeeding and the Use of Human Milk, 1997 • Human milk is the preferred feeding for all infants • Breastfeeding should begin as soon as possible after birth • Newborns should be nursed 8 to 12 times every 24 hours until satiety, usually 10 to 15 minutes per breast. (Crying is a late indicator of hunger.) AAP: Breastfeeding and the Use of Human Milk, 1997 • “Exclusive breastfeeding is ideal nutrition and sufficient to support optimal growth and development for approximately the first 6 months after birth….It is recommended that breastfeeding continue for at least 12 months, and thereafter for as long as mutually desired.” AAP: Breastfeeding and the Use of Human Milk, 1997 • Vitamin D and iron may need to be given before 6 months of age in selected groups of infants (vitamin D, when mothers are deficient or infants not exposed to adequat3 sunlight, iron for those with low iron stores or anemia.) • Fluoride should not be administered to infants during the first 6 months after birth. From 6 months to 3 years only if water supply is severely deficient. AAP: Breastfeeding and the Use of Human Milk, 1997 • “Should hospitalization of the breastfeeding mother or infant be necessary, every effort should be made to maintain breastfeeding preferably directly or by pumping the breasts.” Infant Formulas: AAP • Cow’s milk based formula is recommended for the first 12 months if breastmilk is not available AAP: Cow’s Milk in Infancy • Objections include: – Cow’s milk poor source of iron – GI blood loss may continue past 6 months – Bovine milk protein and Ca inhibit Fe absorption – Increased risk of hypernatremic dehydration with illness – Limited essential fatty acids, vitamin C, zinc – Excessive protein intake with low fat milks Infant Formulas - History • Cow’s milk is high in protein, low in cho, results in large initial curd formation in gut if not heated before feeding • Early Formulas – from 1920-1950 majority of non-breastfed infants received evaporated milk formulas boiled or evaporated milk solved curd formation problems – cho provided by corn syrup or other cho to decrease relative protein kcals Infant Formula - History, cont. • 50s and 60s commercial formulas replaced home preparation • 1959: iron fortification introduced, but in 1971 only 25% of infants were fed Fe fortified formula • Cow’s milk feedings started in middle of first year between 1950-1970s. In 1970 almost 70% of infants were receiving cow’s milk. Soy Formulas • First developed in 1930s with soy flour • Early formulas produced diarrhea and excessive gas • Now use soy protein isolate with added methionine Addition of DHA & ARA • 2001: FDA approves as GRAS • 2002: Ross & Mead Johnson introduce products with DHA and ARA • Cost: 15-20% above standard formulas Formula Regulation • Regulation is by the Infant Formula Act of 1980, under FDA authority • Nutrient composition guidelines for 29 nutrients established by AAP Committee on Nutrition and adopted as regs by FDA • Nutrient Requirements for Infant Formulas. Federal Register 36, 23553-23556. 1985. 21 CFR Part 107. Cow’s Milk Based Formula • Commercial formula designed to approximate nutrients provided in human milk • Some nutrients added at higher levels due to less complete digestion and absorption Protein: Predominant protein of human milk is whey & predominant protein in cow’s milk is casein – Casein: proteins of the curd (low solubility at pH 4.6) – Whey: soluble proteins (remain soluble at pH 4.6) – Ratio of casein to whey is between 40:60 and 30:70 in human milk and 82:18 in cow’s milk – some formulas provide more whey proteins than others Protein, cont. – whey proteins of human and cow’s milk are different and have different amino acid profiles. • Major whey proteins of human milk at a lactalbumin (high levels of essential aa) , immunoglobulins, and lactoferrin( enhances iron transportation) • Cow’s milk has low levels of these proteins and high levels of b lactoglobulin – Infants appear to thrive equally well with either whey or casein predominant formulas. Cow’s Milk Based Formula: Fat & CHO • Fat: butterfat of cow’s milk is replaced with vegetable fat sources to make the fatty acid profile of cow’s milk formulas more like those of human milk and to increase the proportion of essential fatty acids • Cho: Lactose is the major carbohydrate in most cows’ milk based formulas. Product Human Milk Protein g/100 ml Source ~ 1.0 Human milk Fat g/100 ml Source ~3.9 Human Milk Enfamil 1.4 Reduced mineral whey, Nonfat milk 3.6 Gerber 1.5 non fat milk 3.7 Good Start 1.6 Hydrolyzed reduced mineral whey 3.5 Similac (Improved) 1.4 3.7 Lactofree 1.5 Nonfat milk, whey protein concentrate Milk protein isolate 3.6 Palm olein, soy, coconut, high-oleic sunflower Palm olein, soy, coconut, high-oleic sunflower Palm olein, soy, coconut, high-oleic sunflower High oleic safflower, coconut and soy oil Palm olein, soy, coconut, and high oleic sunflower oils Carbohydrate g/100 ml Source ~7.2 Human Milk Lactose 7.4 Lactose 7.3 Lactose 7.4 Lactose, corn maltodextri ne 7.2 Lactose 6.9 Corn syrup solids Formulas with DHA & ARA Ross Mead Johnson Full term Similac Advance Enfamil Lipil Preterm Similac Special Care, Similac Natural Care, NeoSure Advance Enfamil Premature Lipil, Enfacare Lipil Soy Formulas • Protein: soy protein isolate with added methionine • Fat: vegetables oils • Cho: usually corn based products American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Nutrition. Soy Protein-based Formulas: Recommendations for Use in Infant Feeding. Pediatrics 1998;101:148-153. • Soy formulas given to 25% of infants but needed by very few • Offers no advantage over cow milk protein based formula as a supplement for breastfed infants • Provides appropriate nutrition for normal growth and development • Indicated primarily in the case of vegetarian families and for the very small number of infants with galactosemia and hereditary lactase deficiency Possible Concerns about Soy Formulas: AAP • 60% of infants with cowmilk protein induced enterocolitis will also be sensitive to soy protein damaged mucosa allows increased uptake of antigen. • Contains phytates and fiber oligosacharides so will inhibit absorption of minerals (additional Ca is added) • Higher levels of osteopenia in preterm infants given soy formulas • Phytoestrogens at levels that demonstrate physiologic activity in rodent models • Higher aluminum levels Contraindications to Soy Formula: AAP – preterm infants due to increased risk of inadequate bone mineralization – infants with cow milk protein-induced enteropathy or enterocolitis – most previously well infants with acute gastroenteritis – prevention of colic or allergy. Health Consequences of Early Soy Consumption. Badger et al. J Nutr. 2002 • US soy formulas made with soy protein isolate (SPI+) • SPI+ has several phytochemicals, including isoflavones • Isoflavones are referred to as phytoestrogens • Phytoestrogens bind to estrogen receptors & act as estrogen agonists, antagonists, or selective estrogen receptor modulators depending on tissue, cell type, hormonal status, age, etc. Figure 1. Hypothetical serum concentrations profile of isoflavones from conception through weaning in typical Asians and Americans. The values represent the range of isoflavonoids reported by Adlercreutz et al. (6 ) for Japanese (dotted lines) or reported by Setchell et al. (3 ) for Americans fed soy infant formula (dashed line). Should we be Concerned? Badger et al. • No human data support toxicity of soyfoods • Soyfoods have a long history in Asia • Millions of American infants have been fed soy formula over the past 3 decades • Rat studies indicate a potential protective effect of soy in infancy for cancer Hydrolysate Formulas • Whey Hydrolysate Formula: Cow’s milk based formula in which the protein is provided as whey proteins that have been hydrolyzed to smaller protein fractions, primarily peptides. This formula may provoke an allergic response in infants with cow’s milk protein allergy. • Casein Hydrolysate Formula: Infant formula based on hydrolyzed casein protein, produced by partially breaking down the casein into smaller peptide fragments and amino acids. ` AAP Policy Statement Re: Hypoallergenic Infant Formulas (August, 2000) • Currently available, partially hydrolyzed formulas are not hypoallergenic. AAP Policy Statement Re: Hypoallergenic Infant Formulas (August, 2000) • Carefully conducted randomized controlled studies in infants from families with a history of allergy must be performed to support a formula claim for allergy prevention. Allergic responses must be established prospectively, evaluated with validated scoring systems, and confirmed by double-blind,placebocontrolled challenge. These studies should continue for at least 18 months and preferably for 60 to 72 months or longer where possible AAP Policy Statement Re: Hypoallergenic Infant Formulas (August, 2000) Recommendations • 1.Breast milk is an optimal source of nutrition for infants through the first year of life or longer. Those breastfeeding infants who develop symptoms of food allergy may benefit from: – a.maternal restriction of cow's milk, egg, fish, peanuts and tree nuts and if this is unsuccessful, – b.use of a hypoallergenic (extensively hydrolyzed or if allergic symptoms persist, a free amino acidbased formula) as an alternative to breastfeeding. • Those infants with IgE-associated symptoms of allergy may benefit from a soy formula, either as the initial treatment or instituted after 6 months of age after the use of a hypoallergenic formula. The prevalence of concomitant is not as great between soy and cow's milk in these infants compared with those with non–IgE-associated syndromes such as enterocolitis, proctocolitis, malabsorption syndrome, or esophagitis. Benefits should be seen within 2 to 4 weeks and the formula continued until the infant is 1 year of age or older. 2.Formula-fed infants with confirmed cow's milk allergy may benefit from the use of a hypoallergenic or soy formula as described for the breastfed infant. 3.Infants at high risk for developing allergy, identified by a strong (biparental; parent, and sibling) family history of allergy may benefit from exclusive breastfeeding or a hypoallergenic formula or possibly a partial hydrolysate formula. Conclusive studies are not yet available to permit definitive recommendations. However, the following recommendations seem reasonable at this time: a.Breastfeeding mothers should continue breastfeeding for the first year of life or longer. During this time, for infants at risk, hypoallergenic formulas can be used to supplement breastfeeding. Mothers should eliminate peanuts and tree nuts (eg, almonds, walnuts, etc) and consider eliminating eggs, cow's milk, fish, and perhaps other foods from their diets while nursing. Solid foods should not be introduced into the diet of high-risk infants until 6 months of age, with dairy products delayed until 1 year, eggs until 2 years, and peanuts, nuts, and fish until 3 years of age. b.No maternal dietary restrictions during pregnancy are necessary with the possible exception of excluding peanuts; 4. Breastfeeding mothers on a restricted diet should consider the use of supplemental minerals (calcium) and vitamins. Product Prosobee Protein g/100 ml Source 2.0 Soy protein isolate, Lmethionine Isomil 1.7 Soy protein isolate, Lmethionine Nutramigen 1.9 Pregestimil 1.9 Alimentum 1.9 Casein hydrolysate, L-cystine, Ltyrosine, Ltryptophan, taurine Casein hydrolysate, L-cystine, Ltyrosine, Ltryptophan, taurine Casein hydrolysate, L-cystine, Ltyrosine, Ltryptophan Fat g/100 ml Source 3.6 Palm olein, soy, coconut, high oleic sunflower oils 3.7 High oleic safflower, coconut and soy oils 2.7 3.8 3.8 Carbohydrate g/100 ml Source 6.8 Corn syrup solids 7.0 Corn syrup, sucrose, modified corn starch Corn syrup solids, modified corn starch Palm olein, soy, coconut, high oleic sunflower oils 55% MCT, corn, soy, high oleic safflower oils 9.1 6.9 Corn syrup solids, dextrose, corn starch 50% MCT, Safflower and soy oils 6.9 Sucrose, modified tapioca starch Specialty Formulas • Elemental - Neocate • Premature Follow Up - Neosure, Enfamil 22 • Other highly specialized for metabolic conditions Formula Safety Issues - 2002 • Enterobacter Sakazakii in Intensive care units • Powered formula is not sterile so should not be used with high risk infants • FDA recommends mixing with boiling water but this may affect availability of vitamins & proteins and also cause clumping • Irradiation proposed Milk Feedings Cautionary Tales • Cooper et al. Pediatrics 1995. Increased incidence of severe breastfeeding malnutrition and hypernatremia in a metropolitan area. • Keating et al. AJDC 1991. Oral water intoxication in infants. • Lucas et al. Arch Dis Child. 1992. Randomized trial of ready to fed compared with powdered formula. Cooper, cont. • 5 breastfed infants admitted to Children’s hospital in Cincinnati over 5 months period for breastfeeding malnutrition and dehydration – age at readmission was 5 to 14 days – mothers were between the ages of 28 and 38, had prepared for breastfeeding – 3 had inverted nipples and reported latch-on problems before discharge – 3 families had contact with health care providers before readmission including calls to PCP and home visit by PHN Cooper, cont. • at time of readmit none of presenting complaints related to s&s of dehydration, only one infant presented with feeding complaint • wt. Loss at admission: 23%, range 14-32% • Serum Na - mean 186 mmol/l, range 161-214 (136-143 is wnl) • 3 infants had severe complications: multiple cerebral infarctions, left leg amputation secondary to iliac artery thrombus Keating • 24 cases of oral water intoxication in 3 years at Children’s Hospital and St. Louis • Most were from very low income families and were offered water at home when formula ran out • Authors suggest: provision of adequate formula and anticipatory guidance Lucas • 43 infants randomized to RTF or powdered formula • Infants given powdered formula had increased body wt. And skinfold thickness at 3 and 6 mos.. Compared to RTF and breastfed • Powdered formula - 6 of 19 were above the 90th percentile wt/ht, but only 1 of 19 RTF infants • Authors suggest errors in reconstitution of formula Formula Preparation Microwave Protocol (Sigman-Grant, 1992) • Heat only 4 oz or more refrigerated formula with bottle top uncovered • 4 oz bottles < 30 seconds • 8 oz bottles < 45 seconds • Invert 10 times before use • Should be cool to the touch • Always test drops of formula on tongue or top of hand AAP: Timing of Introduction of Non-milk Feedings • Based on individual development, growth, activity level as well as consideration of social, cultural, psychological and economic considerations • Most infants ready at 4-6 months • Introduction of solids after 6 months may delay developmental milestones. • By 8-10 months most infants accept finely chopped foods. Solids: Foman, 1993 • “For the infant fed an iron-fortified formula, consumption of beikost is important in the transition from a liquid to a nonliquid diet, but not of major importance in providing essential nutrients.” • Breastfed infants: nutritional role of beikost is to supplement intakes of energy, protein, perhaps Ca and P Solids: Borrensen - (J Hum Lact. 1995) • Some studies find exclusive breastfeeding for 9 months supports adequate growth. • Iron needs have individual variation. • Drop in breastmilk production and consequent inadequate intake may be due to management errors Solids: Weight Gain • Weight gain: Forsyth (BMJ 1993) found early solids associated with higher weights at 8-26 weeks but not thereafter Solids: Respiratory Symptoms • Forsyth (BMJ 1993) found increased incidence of persistent cough in infants fed solids between 14-26 weeks. • Orenstein (J Pediatr 1992) reported cough in infants given cereal as treatment for GER. Solids Too Early • allergic disease • diarrheal disease • decreased breastmilk production • developmental concerns Too Late • potential growth failure • iron deficiency • developmental concerns AAP: Specific Recommendations for Infant Foods • Start with introduction of single ingredient foods at weekly intervals. • Sequence of foods is not critical, iron fortified infant cereals are a good choice. • Home prepared foods are nutritionally equivalent to commercial products. • Water should be offered, especially with foods of high protein or electrolyte content. AAP: Specific Recommendations • Home prepared spinach, beets, turnips, carrots, collard greens not recommended due to high nitrate levels • Canned foods with high salt levels and added sugar are unsuitable for preparation of infant foods • Honey not recommended for infants younger than 12 months Foman S. Feeding Normal Infants: Rationale for Recommendations. JADA 101:1102 • “It is desirable to introduce soft-cooked red meats by age 5 to 6 months. “ • Iron used to fortify dry infant cereals in US are of low bioavailablity. (use wet pack or ferrous fumarate) The Use and Misuse of Fruit Juice in Pediatrics - AAP, May 2001 • Conclusions • Recommendations 1.Fruit juice offers no nutritional benefit for infants younger than 6 months. 2.Fruit juice offers no nutritional benefits over whole fruit for infants older than 6 months and children. 3.One hundred percent fruit juice or reconstituted juice can be a healthy part of the diet when consumed as part of a well-balanced diet. Fruit drinks, however, are not nutritionally equivalent to fruit juice. 4.Juice is not appropriate in the treatment of dehydration or management of diarrhea. 5.Excessive juice consumption may be associated with malnutrition (overnutrition and undernutrition). 6.Excessive juice consumption may be associated with diarrhea, flatulence, abdominal distention, and tooth decay. 7.Unpasteurized juice may contain pathogens that can cause serious illnesses. 8.A variety of fruit juices, provided in appropriate amounts for a child's age, are not likely to cause any significant clinical symptoms. 9.Calcium-fortified juices provide a bioavailable source of calcium but lack other nutrients present in breast milk, formula, or cow's milk. 1. Juice should not be introduced into the diet of infants before 6 months of age. 2. Infants should not be given juice from bottles or easily transportable covered cups that allow them to consume juice easily throughout the day. Infants should not be given juice at bedtime. 3. Intake of fruit juice should be limited to 4 to 6 oz/d for children 1 to 6 years old. For children 7 to 18 years old, juice intake should be limited to 8 to 12 oz or 2 servings per day. 4. Children should be encouraged to eat whole fruits to meet their recommended daily fruit intake. 5. Infants, children, and adolescents should not consume unpasteurized juice. 6. In the evaluation of children with malnutrition (overnutrition and undernutrition), the health care provider should determine the amount of juice being consumed. 7. In the evaluation of children with chronic diarrhea, excessive flatulence, abdominal pain, and bloating, the health care provider should determine the amount of juice being consumed. 8. In the evaluation of dental caries, the amount and means of juice consumption should be determined. 9. Pediatricians should routinely discuss the use of fruit juice and fruit drinks and should educate parents about differences between the two. C-P-F: Possible Concerns Michaelsen et al. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1995 • Dietary Fat is ~ 50% of Kcals with exclusive breastmilk or formula intake. • Dietary fat contribution can drop to 20-30% with introduction of high carbohydrate infant foods. • Infants receiving low fat milks are at risk of insufficient energy intake. • Fat intake often increases with addition of high fat family foods. C-P-F: Low Energy Density • Low fat diet often means diet has low energy density • Increased risk of poor growth • Reduction in physical activity • Energy density of 0.67 kcal/g recommended for first year of life (Michaelson et al.) C-P-F: Low fat Diets in Infancy • No strong evidence linking fat intake in infancy and adult atherosclerosis • Low weight at 12 months linked to increased risk of mortality from CVD • Very low fat diet may be low in dairy and meats and nutrients from those foods • Very high fat diet may have lower micronutrient content C-P-F: Recommendations • No strong evidence for benefits from fat restriction early in life • AAP recommends: – high carbohydrate infant foods may be appropriate for formula fed infants – no fat restriction in first year – a varied diet after the first year – after 2nd year, avoid extremes, total fat intake of 30-40% of kcal suggested Allergies: Areas of Recent Interest • Early introduction of dietary allergens and atopic response – atopy is allergic reaction/especially associated with IgE antibody – examples: atopic dermatitis (eczema), recurrent wheezing, food allergy, urticaria (hives) , rhinitis • Prevention of adverse reactions in high risk children Allergies: Infancy • Increased risk of sensitization as antigens penetrate mucosa, react with antibodies or cells, provoking cellular response and release of mediators • Immaturities that increase risk: – gastric acid, enzymes – microvillus membranes – lysosomal functions of mucosal cells – immune system, less sIgA in lumen Allergies: Breastmilk • May be protective due to sIgA and mucosal growth factors • Maternal avoidance diets in lactation remain speculative. May be useful for some highly motivated families with attention to maternal nutrient adequacy. Allergies: Breastmilk (Saarinen, 1995) • 235 Helsinki infants born in 1995 • Categorized by duration of breastfeeding, > 6 months, 1-6 months, no or short breastfeeding • Incidence of food and respiratory allergy was greatest in short or no breastfeeding group • Differences persisted at 17 years of age Allergies: Early Introduction of Foods (Fergussson et al, Pediatrics, 1990) • 10 year prospective study of 1265 children in NZ • Outcome = chronic eczema • Controlled for: family hx, HM, SES, ethnicity, birth order • Rate of eczema with exposure to early solids was 10% Vs 5% without exposure • Early exposure to antigens may lead to inappropriate antibody formation in susceptible children. Early Introduction of Foods (Fergussson et al, Pediatrics, 1990) Proportional Hazard Coefficient (p<0.01) For Risk of Chronic Eczema No solid Food before 1.00 4 months 1-3 types of food before 4 months 1.69 4+ types of foods before 4 months 2.87 Allergies: Prevention by Avoidance (Marini, 1996) • 359 infants with high atopic risk • 279 in intervention group • Intervention: breastfeeding strongly encouraged, no cow’s milk before one year, no solids before 5/6 months, highly allergenic foods avoided in infant and lactating mother Allergies: Prevention by Avoidance (Marini, 1996) % of Children With Any Allergic Manifestations (cummulative incidence) 80 60 non-intervention intervention 40 20 0 1 yr 2 yrs 3 yrs Allergies: Prevention by Avoidance (Zeigler, Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 1994) • High risk infants from atopic families, intervention group n=103, control n=185 • Restricted diet in pregnancy, lactation, Nutramagen when weaned, delayed solids for 6 months, avoided highly allergenic foods • Results: reduced age of onset of allergies Allergies: Prevention by Avoidance (Zeigler, Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 1994) Definite or Probable Food Allergy Age Intervention Control p 12 mo 5% 16% 0.007 24 mo 7% 20% 0.005 48 mo 4% 6% ns Allergies: Predicting Risk (Odelram, 1994) • Methods of screening newborns for risk of atopy were compared • Screening tools included many blood tests as well as skin hypersensitivity • Combination of family history of atopy and dry skin in newborn was informative • Sensitivity of 80%, specificity of 85% Allergies: IDDM • Theory: sensitization and development of immune memory to food allergens may contribute to pathogenesis of IDDM in genetically susceptible individuals. • Milk, wheat, soy have been implicated. • Studies are not conclusive. • Breastfeeding and delay in non-milk feedings may be beneficial. Early Childhood Caries • AKA Baby Bottle Tooth Decay • Rampant infant caries that develop between one and three years of age Early Childhood Caries: Etiology • Bacterial fermentation of cho in the mouth produces acids that demineralize tooth structure • Infectious and transmissible disease that usually involves mutans streptococci • MS is 50% of total flora in dental plaque of infants with caries, 1% in caries free infants Early Childhood Caries: Etiology • Sleeping with a bottle enhances colonization and proliferation of MS • Mothers are primary source of infection • Mothers with high MS usually need extensive dental treatment Early Childhood Caries: Pathogenesis • Rapid progression • Primary maxillary incisors develop white spot lesions • Decalcified lesions advance to frank caries within 6 - 12 months because enamel layer on new teeth is thin • May progress to upper primary molars Early Childhood Caries: Prevalence • US overall - 5% • 53% American Indian/Alaska Native children • 30% of Mexican American farmworkers children in Washington State • Water fluoridation is protective • Associated with sleep problems & later weaning Early Childhood Caries: Cost • $1,000 - $3,000 for repair • Increased risk of developing new lesions in primary and permanent teeth Early Childhood Caries: Prevention • Anticipatory Guidance: – – – – importance of primary teeth early use of cup bottles in bed use of pacifiers and soft toys as sleep aides Early Childhood Caries: Prevention • Chemotheraputic agents: fluoride varnishes and supplements, chlorhexidene mouthwashes for mothers with high MS counts • Community education: training health providers and the public for early detection Summary • Breastfeeding should be encouraged • Non milk feedings appropriate by 6 months. • Recommended food choices include fruits, vegetables, legumes, protein sources for breast fed infants, and variety of fat sources. • Individual variations in feeding patterns may be beneficial for infants at risk of allergies, failure to thrive, and nutrition related disease conditions. Bright Futures • AAP/HRSA/MCHB • http://www.brightfutures.org • “Bright Futures is a practical development approach to providing health supervision for children of all ages from birth through adolescence.” Newborn Visit: Breastfeeding • Infant Guidance – how to hold the baby and get him to latch on properly; – feeding on cue 8-12 times a day for the first four to six weeks; – feeding until the infant seems content. – Newborn breastfed babies should have six to eight wet diapers per day, as well as several "mustardy" stools per day. – Give the breastfeeding infant 400 I.U.'s of vitamin D daily if he is deeply pigmented or does not receive enough sunlight. Newborn Visit: Breastfeeding • Maternal care – rest – fluids – relieving breast engorgement – caring for nipples – eating properly • Follow-up support from the health professional by telephone, home visit, nurse visit, or early office visit. Newborn Visit: Bottlefeeding • • • • type of formula, preparation feeding techniques, and equipment. Hold baby in semi-sitting position to feed. Do not use a microwave oven to heat formula. To avoid developing a habit that will harm your infant's teeth, do not put him to bed with a bottle or prop it in his mouth. First Week • Do not give the infant honey until after her first birthday to prevent infant botulism. • To avoid developing a habit that will harm your infant's teeth, do not put her to bed with a bottle or prop it in her mouth. One Month • Delay the introduction of solid foods until the infant is four to six months of age. Do not put cereal in a bottle. Four Months – Continue to breastfeed or to use ironfortified formula for the first year of the infant's life. This milk will continue to be his major source of nutrition. – Begin introducing solid foods with a spoon when the infant is four to six months of age. – Use a spoon to give him an iron-fortified, single-grain cereal such as rice. Four Months, cont. – If there are no adverse reactions, add a new pureed food to the infant's diet each week, beginning with fruits and vegetables. – Always supervise the infant while he is eating. – Give exclusively breastfeeding infants iron supplements. – Continue to give the breastfeeding infant 400 I.U.'s of vitamin D daily if he is deeply pigmented or does not receive enough sunlight. – Do not give the infant honey until after his first birthday to prevent infant botulism. . Six Months • Continue to breastfeed or use iron-fortified formula for the first year of the infant's life. This milk will continue to be her major source of nutrition. • Avoid giving the infant foods that may be aspirated or cause choking (e.g., peanuts, popcorn, hot dogs or sausages, carrot sticks, celery sticks, whole grapes, raisins, corn, whole beans, hard candy, large pieces of raw vegetables or fruit, tough meat). • Learn emergency procedures for choking. Six Months, cont. • Let the infant indicate when and how much she wants to eat. • Serve solid food two or three times per day. • Begin to offer a cup for water or juice. • Limit juice to four to six ounces per day. • Give iron supplements to infants who are exclusively breastfeeding. Nine Months • Start giving the infant table foods in order to increase the texture and variety of foods in his diet. • Encourage finger foods and mashed foods as appropriate. • Closely supervise the infant while he is eating. • Continue teaching the infant how to drink from a cup. • Continue to breastfeed or use iron-fortified formula for the first year of the infant's life.