A Comparative Analysis of the Divorce Law in

England and Denmark

Thesis: CLM/MA in LSP

English Department

Legal language/comparative law

Anne Hofmann Larsen

Supervisor: Bente Jacobsen

Number of characters, thesis: 176,987

Number of characters, summary: 4,207

September 2010

The Aarhus School of Business

Table of contents

1. Introduction ...........................................................................

5

1.1 Problem statement ............................................................................

1.2 Delimitation of study .........................................................................

1.3 Method and structure .........................................................................

6

7

10

2. Theory .................................................................................... 16

2.1 The comparative law theory ............................................................... 16

3. A historical perspective ......................................................... 19

3.1 The legal systems ................................................................................. 19

3.1.1 Acceptance of the Civil law tradition ..............................................

20

3.1.1.1 Common law tradition ......................................................... 20

3.1.1.2 Civil law tradition.................................................................. 21

3.1.2 The sources of law and the principles behind a legal decision .......

22

3.1.2.1 Common law tradition .......................................................

3.1.2.2 Civil law tradition ...............................................................

22

24

3.1.3 Procedure, judges and lawyers and their educational background

25

3.1.3.1 Common law tradition........................................................

3.1.3.2 Civil law tradition ...............................................................

25

26

3.2 Sub conclusion .................................................................................... 29

2

3.3 The historical development of the divorce law in England ................... 30

3.3.1 From 1500 to 1857 – from divorceless society to divorce by

'Private Act of Parliament'...............................................................

3.3.2 From 1857 to 1923 – from judicial divorce toward elimination

of the 'double sexual standard' .......................................................

3.3.3 From 1923 to 1937 – from elimination of the 'double sexual

standard' toward the first extension of the grounds for divorce ....

3.3.4 From 1937 to 1969 – from the first extension of the grounds for

divorce toward one sole ground and the decline of the

matrimonial offence doctrine..........................................................

30

31

33

34

3.4 The historical development of the divorce law in Denmark .................. 39

3.4.1 From 1500 to 1922 – from divorceless society to unregulated

administrative separation and divorce ............................................. 39

3.4.2 From 1922 to 1969 – from the first secular marital act

toward easier legal separation (separation)...................................... 41

3.4.3 From 1969 to 2007 - from easy legal separation toward

further reduction of legal separation time and abolition of guilt..... 42

3.5 Sub conclusion ..................................................................................... 46

4. Existing divorce law in England and Denmark .................... 47

4.1 Existing grounds for divorce in England ................................................ 47

4.2 Existing procedure for obtaining a divorce in England ........................... 51

4.2.1 Undefended divorces ....................................................................... 51

4.2.2 Defended divorces ............................................................................ 52

4.2.3 The two-part process: decree nisi – decree absolute........................ 52

4.3 Existing grounds for divorce in Denmark .............................................. 54

4.4 Existing procedure for obtaining a divorce in Denmark ......................... 57

4.4.1 The administrative procedure........................................................... 57

4.4.2 The judicial procedure ...................................................................... 58

3

5. Comparative analysis ............................................................. 59

5.1 Existing grounds for divorce in England and Denmark .......................... 59

5.1.1 'Ground' and facts for divorce .......................................................

5.1.2 Distinction between fault/no-fault.................................................

5.1.3 Bar to divorce .................................................................................

5.1.4 Individual 'grounds' and facts for divorce ......................................

5.1.5 Wording of the Acts .......................................................................

59

60

60

60

63

5.2 Existing procedure for obtaining a divorce in England and in Denmark . 64

5.3 Sub conclusion .................................................................................... 67

6. Analysis and discussion of why the established differences exist . 68

6.1 Sub conclusion ...................................................................................... 76

7. Conclusion and perspectives .....................................................

77

8. Summary ..................................................................................

80

References ...................................................................................

82

Appendices ..................................................................................

88

4

1. Introduction

From earliest years, in both England and Denmark, and until around the 18th and 19th centuries,

getting married was a relatively uncomplicated affair, in which the law did not involve itself too

much; an individual was free to 'marry' merely by the exchange of vows, or by the act of sexual

intercourse with their partner1.

Getting a divorce, on the other hand, was a completely different, highly controversial and

complicated affair since the Christian idea of marriage as an indissoluble life-long union prevailed

in both countries2; this view becomes unmistakably clear in the two statements below.

"Those whom God had joined together were not to be put asunder by any human act" 3.

"Hvad Gud har sammenføjet, må et menneske ikke adskille"4 (What God has joined together, a

human being must not put asunder).

To judge from the above statements, it seems that in ancient society the public view, i.e., that of

the Church, on divorce was virtually the same in England and Denmark; according to the medieval

Canon law5 6, divorce was not acknowledged, except in extraordinary cases.

In the meantime, however, divorce has become an available legal remedy obtainable before a

judicial court7, and the rules on divorce matters have developed continuously since then and been

relaxed significantly in both countries.

Similarly today, at least on the surface, the two countries appear to be relatively alike in rather

many aspects: both are western democracies, members of the EU, have a predominantly Christian

population8, and a practical and non-philosophical approach to many things in life9. And this is

probably the reason why the two countries are so often being compared in various respects.

Seen in this light, one may well be tempted to ask what exactly justifies a thesis on a comparative

analysis of the divorce law in England and Denmark when there seems to be so relatively little

difference between the two countries.

1

Rodgers, M.E. 2004. Understanding Family Law. Routledge-Cavendish, p. 1, Nielsen, Linda og Vorstrup, Jesper. 2001.

Familieretten. 3. udg. Forlaget Thomsen, p. 23, Tamm, Ditlev. 1989. Lærebog i Dansk Retshistorie. Foreløbig udg. Jurist- og

Økonomforbundets Forlag, p. 47, and Glendon, Mary Ann. 1989. The Transformation of Family Law. The University of Chicago

Press, p. 19.

2 Nielsen, Linda. 2008. Skilsmisseret – de økonomiske forhold. København: Thomsen Reuters, p. 23, and Standley, Kate. 2006. Family

Law. 5th ed. New York: Palgrave Macmillan Law Masters, p. 146.

3 Cretney, Stephen. 2003. Family Law in the Twentieth Century. Oxford – New York: Oxford University Press. p. 161.

4 Nielsen, Linda og Vorstrup Jesper. op.cit., p. 23.

5 Canon law is the body of laws and regulations made by or adopted by the ecclesiastical authority, for the government of the

Christian organization and its members. Colloquially also referred to as 'Church law'.

6 Andersen, Ernst. 1971. Familieret. 3. udg. København: Juristforbundets Forlag, p 133.

7 Cretney, Stephen. 2003. Principles of Family Law.7th ed. London: Thomson. p. 269, and Tamm, Ditlev. op.cit., p. 236

8 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anglicanism, and

http://www.dr.dk/Tro/Temaer/Troens%20rødder/Kjeld%20Holm/20060809103729.htm

9 http://frost.blogs.berlingske.dk/2008/09/22/farvel-til-danmark-2-%e2%80%93-et-konsensussamfund/

5

But as is often the case, closer inspection reveals that under the surface things tend to be more

complex. And indeed, studying family law at the Aarhus School of Business, Aarhus University, at

the 2nd semester legal language course programme, ASB Master Programme, soon made it clear to

me that this legal field covers an area whose rules of law differ quite remarkably in a number of

ways in the two countries. This finding inspired me not just to make a thorough investigation into

the area in order to carry out a comparative analysis to delineate the differences, but also to make

attempts to find out why these differences exist.

Hence, the overriding purpose of this thesis is indeed to make a comparative analysis, but perhaps

to some extent in a more untraditional way, since it will combine the rigidity of outlining the

existing rules of the divorce law with the more soft approach of investigating the main question of

this study namely, why the established differences, in substance and in tone, within the two legal

areas of the divorce law in question namely, 'the existing grounds for divorce' and 'the existing

procedure for obtaining a divorce' exist (see also 1.1 below). Thus, the readership should be

prepared to read a comparative analysis that distinguishes itself from a traditional comparative

analysis in that it treats only selected sections and provisions within the legal areas in question,

and be willing to accept some sacrifices both in range and depth of coverage (see subchapter 1.3 –

Method and structure). It is my hope that this way of building up and delimiting the study will

provide the readership with a more holistic view on and a better understanding of the subject

matter.

1.1

Problem statement

Based on a comparative analysis that will establish the differences, in substance and in tone,

within the following two areas of the divorce law in England and Denmark namely,

-

the existing grounds for divorce, and

the existing procedure for obtaining a divorce,

the main question that I will attempt to answer in this study is:

Why do these differences, in substance and in tone, within the two above-mentioned areas of the

divorce law exist?

6

1.2

Delimitation of study

It seems natural to consider family law as a kind of story starting with marriage and sometimes

ending in divorce. Seen from this perspective, and if only divorce, which is the subject matter of

this study, is considered, it might have seemed obvious to include property and finance on divorce

and arrangement for children, to complete the story, so to speak. These two areas, however, have

been left out. Not because they are of less importance and interest, but simply due to time and

space limitations.

Instead only the areas governing the grounds for divorce and the procedure for obtaining a

divorce will be treated here. It is my belief that selecting only these two areas as the point of

departure for this thesis cannot only be justified in terms of time and space, but also in terms of

substance, i.e. if we approach divorce from either a human or material aspect.

As a case in point, in a simple world, the story of family law could probably be reduced to two

'chapters', namely marriage and divorce, focusing exclusively on the human aspect - i.e. the desire

to marry/divorce or not – only, without having regard to the material aspect - i.e. ancillary relief,

financial settlement and arrangement for children. With this division in mind, it could be argued,

and perhaps reasonably so, that the procedure for obtaining divorce should fall under the material

aspect. However, I have chosen to categorise this area under the human aspect as the procedure

is deemed necessary in order to obtain the status 'divorced' in the same way as some kind of

marriage ceremony is required in order to obtain the status 'married'. It is on the basis of these

considerations that I find it defensible and relevant to delimit this study to the two areas

mentioned and make them the basis of the investigation with regard to establishing why the

differences within these two areas exist.

Having selected the areas for the comparative analysis and established, by way of introduction,

that a number of differences exist, the next point to be considered is where to search for an

answer to why they exist? At first, it seems obvious to search for it in the concepts behind the

legal system (also referred to as the legal system/culture argument) of the two countries and in

the historical development (also referred to as the historical development argument) of their

respective divorce law. And this is also where I have decided to look for an answer. Scholarly

support for this choice can be found by Phillips and Stone at the end of this subchapter 1.2 as well

as by Shears and Stephenson who say that the reason for any given character of the law is to be

sought in the evolution of the legal system or legal tradition10 11. It will be assumed in this thesis

that the legal tradition to which the Danish legal system belongs is the Civil law tradition12, which

10

Most experts operate with three influential legal systems or traditions in contemporary world: Common law, Civil law and

Socialist law. Zweigert, Konrad. 1998. An Introduction to Comparative Law. 3rd ed. Oxford – New York: Oxford University Press. pp.

64-188 and Merryman, John Henry. 1985. The Civil Law Tradition. 2nd ed. California: Stanford University Press. pp. 1-5.

11 Shears, P. and Stephenson, G. 1996. James' Introduction to English Law. Butterworths, London, Dublin and Edinburgh. p. 8.

12

Civil law in this context must not be confused with what is called 'civilret' in Danish. It is one of the two main categories into

which Danish law is divided. The other category is called 'offentligret' in Danish. The English translation of the two terms would be

'private law' and 'public law' respectively. 'Civilret' is also often referred to as 'privatret' or 'borgerlig ret' in Danish and would also

7

traces its origin directly to Roman law that bases its existence on the code of Roman law called

Corpus Juris Civilis,13 and contains huge mutual differences, although this adherence has been

subject to much debate among experts14. Likewise it will be assumed that the legal tradition to

which the English legal system adheres is the Common law tradition, which dates back to the

conquest of England by the Normans in 106615.

With regard to the historical development of the divorce law (the historical development

argument), since no single model of change exists that can explain the history of marriage

breakdown and divorce in one country for all periods of time and for all classes of society, it is

difficult to confine the chronology of changes in attitudes towards divorce, and much more

difficult to explain it. Those who claim that either the law has always formed marital practices or

vise versa, or that the causes of change were at the end legal, economic and social, or cultural and

moral, or intellectual, is presenting a too simplistic conclusion to the readership - a conclusion,

which is not supported by evidence16. As Lawrence Stone puts it: 'History is messier than that'17.

Everything in the social, economic and legal fields interacts, and the reasons may lie anywhere in

the whole realm of social life18. Therefore it would be too much to say that one must

systematically master all this knowledge before one is allowed to begin any kind of comparative

work and attempt to find answers to why differences exist19. Consequently, and despite Stone's

and Phillips' recommendation that an analysis on divorce laws always must relate to wider

considerations of society, I have chosen to focus mainly on the development of legal changes of

the two areas of the divorce law mentioned in the problem statement.

be conveyed into 'private law' in English.

http://www.denstoredanske.dk/Samfund,_jura_og_politik/Jura/Almindelig_retsl%C3%A6re,_retsfilosofi_og_terminologi/civilret.

13 When reference is made to Roman law this is normally to be understood as a reference to a specific code of Roman law, namely

'Corpus Juris Civilis' issued by the Roman Emperor Justinian during the years 529-534. With the fall of the Roman Empire, the

'Corpus Juris Civilis' fell into disuse. However, late in the 11th century there was 'a revival of Roman law' – conceded to have its

beginning in Italy where the first modern European university appeared at which law was a major object of study. Over the years,

though, the original Roman law was influenced by different legal scholars resulting in Roman law becoming a hybrid consisting of

many heterogeneous legal directions. This mix of different legal directions was transmitted to Civil law and the reason why there

are so relatively many variations of the Civil law tradition today. Merryman, John Henry. op.cit., pp. 6-13.

14 Zweigert is of the opinion, as is Merryman, that it would be correct to attribute the Nordic laws, which comprises Danish law, to

the Civil law tradition although the laws must undoubtedly form a special legal tradition alongside the Romanistic and German legal

traditions of Civil law, since Roman law has played a smaller role in the legal development of the Nordic countries than it has in

Germany. Zweigert, Konrad. op.cit., p. 277 and Merryman, John Henry. op. cit., p. 5. However, Sundberg disagrees with this stance

claiming that Denmark belongs to the overall Civil law tradition as there is no such thing as a special Scandinavian Civil law

tradition. Sundberg, Jacob.W.F. 1969. Civil Law, Common Law and the Scandinavians. Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell.p. 204. The

adherence of English law to the Common law tradition seems to be indisputable though. See also note 15.

15 It is correct that before the Norman Conquest in 1066, England did have legal practices under the Anglo-Saxon kings. But

according to experts, English legal history begins by the Norman Conquest in 1066. Although the Normans did not make a sudden

change in English law in 1066, the subsequent effect of the Norman invasion on the law was so profound that earlier influences can

be ignored. It is estimated that the formation of the Common law of England was complete by about 1250.This should be seen in

contrast to the Civil law tradition which has existed, however in various sub-traditions and subject to many changes, since the reign

of the Roman emperor Justinian in the 6th century A.D. Zweigert, Konrad. op.cit., p. 182, and Tamm, Ditlev. 2009. Global Retskultur

– en indføring i komparativ ret på historisk grundlag. Frederiksberg: Samfundslitteratur. p. 35. See subchapter 3.1 for further detail

on the legal systems.

16 Phillips, Roderick. 1988. Putting Asunder. A history of divorce in western society. Cambridge – New York – New Rochelle –

Melbourne – Sydney: Cambridge University Press p. 630-640.

17 Stone, Lawrence. 1990. Road to Divorce. Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 27.

18 Zweigert, Konrad. op.cit., p.44.

19 Ibid. p.36.

8

Finally, as to subchapters 3.3 and 3.4 - The historical development of the divorce law in England

and Denmark - my reason for making the beginning of the 16th century the point of departure for

the outlining of the this subchapter, is that with the Reformation followed a time that marked a

change away from a restrictive divorceless society towards a secularized20 society that slowly

started to accept and tolerate some kind of dissolution of marriage21. It also follows from the

relatively long time period subject to investigation that subchapters 3.3 and 3.4 cannot be treated

in detail.

Based on these considerations, a definition and description of the legal systems together with a

description of the historical development of the divorce law in England and Denmark appear to be

both relevant and appropriate fields of study in an attempt to answer the main question of this

study.

20

Refers to the decline of formal and informal religious or spiritual influences on political, social, and personal life and their

replacement by non-religious influences. Phillips, Roderick. op. cit., p. 192.

21 Dübeck, Inger. 1994. Introduktion til Dansk Ret. Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft. p. 13. Cretney, Stephen. 1992. Elements of Family

Law. London: Sweet & Maxwell. p. 30 and Graversen, Jørgen m.fl. 1980. Familieret. København: Juristforbundets Forlag. p. 4.

9

1.3

Method and structure

Chapter 1 – Introduction

This chapter introduces the readership to the subject matter of this study. Delimitation as well as

the method and structure of the thesis are also provided for in this chapter.

Chapter 2 - Theory

This chapter contains subchapter 2.1 – The comparative law theory which is concerned with an

outline of the elements on which the comparative law theory builds. The structure is mainly based

on Lando's and Zweigert's presentation of the comparative law theory, however, structured so as

to best explain its application on this study.

Chapter 3 – A historical perspective

This chapter contains three subchapters namely:

Subchapter 3.1 – The legal systems

The structure chosen for subchapter 3.1 the legal systems is based on a number of criteria thought

most relevant to retrieve the essence of each of the two legal traditions: Common law and Civil

law, and subsequently the differences between them. Inspiration for the selection of these criteria

is, in the main, found in Sundberg's book22, but also in Edlin's book23. Since their points of

departure for analysing these legal traditions differ from mine, the criteria have been slightly

modified in order to fit the purpose of this study. Given the nature of theorizing about concepts

such as Common law and Civil law, the division based on the above criteria will inevitably overlap

since no one criteria can be understood in isolation from the others. Both Sundberg and Edlin offer

a simplistic structure compared to Merryman's structure, for instance, which is more

comprehensive and detailed. Despite the simplicity of the structure applied by Sundberg and Edlin,

it grasps, in my view, the complexity of the nature of theorizing about legal systems, because it

uses the overlap mentioned above in a complementary way that furthers understanding.

Subchapter 3.3 – The historical development of the divorce law in England

In this subchapter the historical development of the divorce law in England will be outlined. To

present the readership with a structured overview of the development, the subchapter has been

divided into time periods centring on the revisions of the English divorce law. As the main focus is

on the development of the substantive law, the procedural law will not be included in the

overview table available at the end of the subchapter, but will of course be mentioned throughout

the subchapter.

Subchapter 3.4 – The historical development of the divorce law in Denmark

The structure of this subchapter is similar to the one applied to subchapter 3.3. However, the

statutory amendment made in 2003 to the Danish Formation and Dissolution of Marriage Act (Lov

22

23

Sundberg, Jacob.W.F. op.cit.

Edlin, Douglas E. 2007. Common Law Theory. Cambridge University Press.

10

om ægteskabs indgåelse og opløsning) is considered insignificant in substance24 and, therefore,

will not be treated under a separate headline. Translations into English of the Danish terms are my

translations. The translations are followed by the original Danish terms in italic. In general, the

English terms used to describe the historical development of the divorce law in Denmark and

other circumstances relating to Denmark in chapters 4, 5 and 6 are predominantly source-text

oriented25.

Chapter 4 – Existing divorce law in England and Denmark

This chapter contains four subchapters namely:

Subchapter 4.1 – Existing grounds for divorce in England

This subchapter will make an outline of the existing ground for divorce in England. Under PART I of

the Matrimonial Causes Act 1973 (MCA 1973) only Divorce, sections 1 and 3 will be treated in

detail. Sections 2, 5 and 10, except 10A, will not be treated in detail. For details on these sections

appendix 1 may be consulted. Inspiration for the selection of sections and structure of this

subchapter is based mainly on the structures found by the authors treating this area26.

Subchapter 4.2 – Existing procedure for obtaining a divorce in England

This subchapter will make and outline of the existing procedure for obtaining a divorce in England.

The Family Proceedings Rules (FPR) 1991 which govern the divorce procedure will not be treated

in detail to the same extent as the MCA 1973 in subchapter 4.1. An outline of the overall principles

of the procedure will be sufficient to show relevant and significant differences between the two

countries' divorce procedure and hence, no specific references will be made to any sections or

rules as this would be beyond the scope of this study. Support for this overall approach is also

found by the authors treating this area whose approaches are very varying and predominantly

treated from an overall perspective. Consequently, the wording of the rules and provisions

governing the procedure will not be subject to analysis in chapter 6. Finally, this approach is also in

line with the limited focus attributed to the divorce procedure in subchapters 3.3 and 3.4.

Subchapter 4.3 – Existing grounds for divorce in Denmark

This subchapter will make an outline of the existing grounds for divorce in Denmark. Sections 31 to

36 of the Danish Act to Consolidate the Law on Formation and Dissolution of Marriage 2007

(DACLFDM 2007) (Lovbekendtgørelse nr. 38 af 15/01/2007 om ægteskabs indgåelse og opløsning)

will be treated in detail in this subchapter. However, the grounds for legal separation will be

mentioned in brief as they are essential to the understanding of the importance of legal

separation as ground for divorce. To help the readership, a translation into English of the original

Danish sections mentioned above as well as sections 6, 9 and 23 of the Act will be available in

appendix 3. Sections 6, 9 and 23 will also appear in appendix 2. Otherwise, the structure of this

subchapter is similar to that of subchapter 4.1.

24

Lund-Andersen, Ingrid. 2003, 5.udg. Familieret. Jurist- og Økonomforbundets Forlag. p. 190.

Source-text oriented translation focuses on the form and content of the source text. Scholdager, Anne. 2008. Understanding

translation. Aarhus: Academica. p. 71.

26 Herring, Jonathan. 2009, 4th ed. Family Law. Harlow: Longman Law Series and Standley, Kate. op. cit., among others.

25

11

The translation available in appendix 3 is based on a predominantly source-text oriented

macrostrategy27 as the skopos of the target text is to focus on the source text culture both with

regard to content and wording. To create uniformity in relation to the presentation of the Danish

sections, the English layout has been copied to avoid confusion in connection with the Danish §sign. Although English grammatical and syntaxical conventions have been observed, which slightly

pulls the translation in a target-text oriented direction on the microstrategic level28, focus is still on

the source text.

Subchapter 4.4 – Existing procedure for obtaining a divorce in Denmark

This subchapter will make an outline of the existing procedure for obtaining a divorce in Denmark.

The structure of this subchapter is based on the same principles as those described above under

subchapter 4.2.

Chapter 5 - Comparative analysis

This chapter constitutes a comparative analysis based on the findings in chapter 4 and thus

establishes the differences within the two selected areas mentioned in the problem statement. In

subchapter 5.1, first the content then the wording of the sections concerned with the grounds for

divorce are compared. In subchapter 5.2, the overall procedure for obtaining a divorce in the two

countries is compared.

Chapter 6 – Analysis and discussion of why the established differences exist

This chapter analyses and discusses why the differences established in chapter 5 exist. The

headline structure will not follow that of chapter 5 as the explanations and arguments overlap to a

large extent. Some of the suggestions and findings may appear oversimplified in some regards.

However, the areas treated seem to be relatively complex and thus calls for some simplicity to

illustrate the explanations for the existence of the differences. Moreover, every single difference

established in chapter 5 will not necessarily be treated in chapter 6 as this would be beyond the

scope of this study and because it would be too much at the expense of the overall understanding

of the main differences. As the literature analysing the Danish legislation within the two areas

subject to investigation is very scarce, the discussion and findings to this purpose will be based on

my own analyses to a very high degree.

27

Macrostrategies refer to the overall approaches available to the translator. There are normally two macrostrategies available.

The source-text oriented macrostrategy which focuses on the form and content of the source text, and the target-text oriented

direction/macrostrategy which focuses on the effect of the target text. Scholdager, Anne. op.cit., p. 71.

28 On the microstrategic level the translator deals with specific problems in connection with words, phrases and sentences. The

macrostrategic choice should normally be reflected in the applied microstrategies and vise versa. Scholdager, Anne. op.cit., p. 89.

12

Chapter 7 – Conclusion and perspectives

This chapter concludes on the analysis and discussion in chapter 6 and presents some perspectives

with regard to future reforms of the divorce law in England and Denmark as well as touches briefly

upon a prospective future harmonisation of the divorce law on a European level.

Sub conclusions

Sub conclusions have only been included where they appear to be relevant that is after

subchapters 3.1, 3.3, 3.4 and after chapters 5 and 6.

Evaluation of information sources:

My main reason for using several books covering the same subject for the preparation of

subchapter 3.1 the legal systems is that some of the authors seem slightly 'coloured'. John Henry

Merryman, Legrand and Friedman who are all presumably children of the Common law tradition

have, not unexpectedly, a tendency to favour the Common law system. The same appears to be

true for Zweigert and Jacob W.F. Sundberg, however, in reverse. Lando seems to have chosen a

more neutral approach to the subject, but is however inclined to favour the Civil law tradition to

which he also must be assumed to belong. So, by contrasting these authors, I believe I have been

able to present the readership with a balanced presentation of the subject matter.

As to a description of the historical development of the divorce law in England, an amazingly huge

and relevant amount of English literature is available. Stephen Cretney, who has written several

books on the subject, and who is often cited and referred to in other books, has been an

invaluable source for the preparation of this subchapter. Together with Philips and Stone he

provided me with different approaches, including explanations, to the subject. The aim of their

books is specifically to explain the law as well as to describe the historical background and analyse

the factors underlying the law's development. Unfortunately, the same number of books on the

development of the divorce law in Denmark is not available, it seems. The most profound

overview of the historical development of the divorce law in Denmark is given by Ernest Andersen

in his book Familieret from 1971. Linda Nielsen and Graversen provided me with a structured

timeline of historical events, but no detailed description. This obliged me to consult the primary

sources that is the Danish acts on formation and dissolution of marriage throughout the period in

question. Furthermore, the development of the Danish divorce law seems difficult to grasp

although it appears less complex than the English. The reason could be that the subject has not

been thoroughly elaborated on and that some legal remedies on divorce developed in Denmark

but were not expressly stipulated in the statutes29.

As to the validity of the sources, the MCA 1973 and the DACLAFDM 2007 can be considered valid

information sources as they are primary sources. The books listed in the reference list of this

thesis, both English and Danish, are secondary sources. There seems to be no reason to question

their validity either. The books seem to be written on topics in the authors' area of expertise. The

authors are all associated with a reputable institution or organization primarily the legal

29

Andersen, Ernst. op.cit., pp. 147 and 151.See also section 3.4.3 of this thesis and note 241.

13

department of various universities. The authors' names are often cited in other sources30 or

bibliographies31, and by other scholars and many of the sources are published by a university

press. Furthermore, most of the books have been revised and updated and the authors are very

much in agreement on the ideas and arguments advanced. The articles referred to in this study

have all been peer-reviewed and the web-pages used have been appraised according to the same

criteria as the other sources. Therefore, there seems to be no reason to question their validity

either.

The readership

The intended readership is, in the main, the English language student at ASB. However, also

people in general who has an interest in and some knowledge of legal language, the law and the

legal system prevalent in England and Denmark, respectively. Irrespective of the narrow legal field

of divorce law treated here, it is my hope that this study may not just provide the readership with

a useful insight into the selected areas of the current divorce law, but also offer some background

knowledge of the legal systems so as to facilitate, hopefully, the understanding of possible

differences within other legal fields between the two countries .

Extension of the Acts

The Matrimonial Causes Act 197332 and the Family Proceedings Rules 1991, as amended over time

extend only to England and Wales33. Scotland and Northern Ireland have separate legislation

governing these areas. The Danish Act to Consolidate the Law on Formation and Dissolution of

Marriage 2007 (DACLFDM 2007) (Lovbekendtgørelse nr. 38 af 15/01/2007 om ægteskabs indgåelse

og opløsning)34, as amended extends only to Denmark. However, it may be extended to both

Greenland and the Faroe Islands by Ministerial Regulation (kgl. anordning) no 307 of 14 May 1993,

as amended and no 37 of 22 January 2002, as amended, respectively35. For the sake of simplicity,

when reference is made to Acts applicable to England and Wales, only England is mentioned.

Definitions

Words such as 'tradition', 'family', 'system' and 'world' are used interchangeably when describing

the legal systems. Furthermore, when reference is made to 'Common law' this is to be interpreted

as the Common law of England that is Common law in its narrow sense, namely Common law as

opposed to 'statute law' (also called legislation or positive law), enacted by the English Parliament,

on the one hand, and Equity36, on the other. When reference is made to Common law in its broad

sense, it will appear from the context. Judge(s) and court(s) are also used interchangeably.

30

Herring, Jonathan. op. cit., pp. 116, 123 and 125.

Glendon, Mary Ann. op. cit., Abbreviations and Lund-Andersen, Ingrid. op. cit., XXXI-XL.

32 http://www.opsi.gov.uk/revisedstatutes/acts/ukpga/1973/cukpga_19730018_en_1

33 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Laws_in_Wales_Acts_1535%E2%80%931542

34 https://www.retsinformation.dk/Forms/R0710.aspx?id=31944. See also appendix 4.

35 Rasmussen, Nell. 2007. Lærebog i familieret. 2. udg. DIKE ApS. p. 192. See also appendix 4.

36 Equity was created during the Middle Ages as a supplementary legal system to Common law. It provided a remedy for types of

wrongs for which the Common law courts could grant no remedy. In the Common law courts the only remedy was damages. As

Equity is a reason built on moral, conscience and fairness, a remedy obtainable in Equity is for example 'specific performance'.

Barker, David and Padfield, Colin. 2001. Law made simple. 10th ed. Oxford: Elsevier. pp. 9-11.

31

14

For the sake of verbal economy, the main Acts will be written in full the first time they are

mentioned. Subsequently, they will be referred to in their abbreviated forms except where

inappropriate.

The terms 'spouse' and 'party' are used interchangeably. The masculine gender 'he/his' includes

the female gender.

To avoid repetitions and too many heavy sentences and to obtain fluency, 'divorce law' will be

used for 'the existing grounds for divorce' and 'the procedure for obtaining a divorce', where

appropriate.

Where reference is made to family law this also covers divorce law in both countries.

Where quotation marks are used around 'grounds', 'grounds' refer to both the ground for divorce

and the five facts in England and to the grounds for divorce in Denmark. It is surprising that

Herring for instance despite his massive criticism of the existing English divorce law especially his

mention of the law's state of confusion as a result of the use of both 'grounds' and facts37, does

not always clearly distinguish between 'grounds' and facts himself38.

The two research areas, selected in an attempt to determine why the established differences exist,

the historical development of the divorce law and the legal systems of the two countries, referred

to in subchapter 1.2, will also be referred to as the historical development argument and the legal

system/culture argument, particularly in chapters 6 and 7.

Appendices

Appendices 1, 2 and 3 contain only the relevant sections of the MCA 1973 and the DACLFDM 2007.

Besides, appendices 2 and 3 do not list the sections according to numerical order but according to

relevance. As to appendix 4, since I had no access to add text in lawyer Jørgen U. Grønborg's

email, I have made a separate Word-document with selected answers and written my translation

below. However, the original email is attached as evidence.

37

38

Herring, Jonathan. op. cit., p. 115.

Ibid. p. 109.

15

2.

Theory

Subchapter 2.1 is concerned to go through the theory applicable when making a comparative

analysis, namely the comparative law theory39. As already mentioned, this study may be

categorised, to some degree, as an untraditional comparative analysis. Nonetheless, the

comparative law theory still applies.

2.1 The comparative law theory

As noted above, the theory applied in this thesis will be that of comparative law. Basically, this

theory can be contemplated as a hybrid. As a rule, it builds from five blocks each of which, for the

most part, consists of two principles/strategies from which the user must choose either the one or

the other. However, both strategies within a block may be applied in the same study. Each block

and its strategies must be considered before starting the comparative work.

First, the theory has two different aims. In its theoretical-descriptive form, the principal aim is to

say 'how' and 'why' certain legal systems and provisions are different or alike. The other form,

being the applied form, has the aim of suggesting how a specific problem can most appropriately

be solved under the given circumstances40.

Second, the comparative law theory offers two distinct approaches - the macro and

microcomparison approach. The macrocomparison compares the spirit and style of different legal

systems. The microcomparison, by contrast, deals with specific legal institutions or problems.

However, the dividing line between these two approaches is flexible as the line may be difficult to

draw41.

Third, yet another principle must be taken into consideration, namely the principle of functionality.

The principle departs from the idea that every society faces the same problems basically and

frequently solves these problems by quite different rules, though often with similar results. The

question posed when applying this principle is 'How a certain country/society solves this particular

problem?' The principle is often used, because law rules may not always be the appropriate point

of departure for a comparison of a given law of two or more countries since the rules of one legal

system may not always be transferrable to the legal system of the other country. It could also be

that the rules in question only exist in one of the two countries subject to comparison – and

therefore not functionally comparable42.

39'Comparative

law' is the comparison of the different legal systems of the world. Zweigert, Konrad. op. cit., p. 2. As outlined in the

problem statement of this study, the comparison here will be between England and Denmark within the areas mentioned.

40 Ibid.

41 Ibid. p. 5.

42

Lando, Ole. 2006. Kort indføring i komparativ ret. 2. udg. Jurist- og Økonomforbundet. pp. 181-183.

16

Fourth, the comparative law theory provides two different strategies of presenting foreign and

domestic law. The first one is the dynamic strategy43 that presents the development of the law

throughout time. The other one is the static strategy44 that presents the law at a given time, often

current law45.

Finally, the theory puts forward two methods of structure. The first method is called the

Länderbericht method46. It is normally used where a general comparison of legal rules is made. It is

also appropriate where the legal systems deviate significantly from each other within the area

subject to investigation. This method demands relatively much space, but gives the readership a

good overview in that it provides answers to a specific question within a given legal system in

relation to other questions within the same system. The other method is called the analytical

method47 and is primarily used where the legal systems of two or more countries subject to

comparison are very similar thus enabling the subject matter in question to be treated jointly for

the countries/legal systems in focus48.

In this study:

The theoretical-descriptive form will be applied as the aim is to investigate 'how' and in particular

'why' differences between the two selected areas of the divorce law in England and Denmark

exist.

The predominant approach will be that of microcomparison since this approach will be used on

the traditional comparative analysis carried out in chapters 4 and 5. However, the

macrocomparison approach will be applied in the chapter on the legal systems – subchapter 3.1 as well as in the chapter on the historical development of the divorce law in England and Denmark

– subchapters 3.3 and 3.4. As the dividing line between the two approaches is flexible, there will

be elements of the microcomparison approach in the two last-mentioned subchapters as well.

The principle of functionality will be used here in order to establish the differences of the two

countries' existing divorce law, which is regulated through legislation 49. However, since the

overriding question of this investigation is a 'why-question', namely 'Why do the established

differences, in substance and in tone, within the two selected areas of the divorce law exist?' the

principle of functionality may not be used to the same extent and in the exact same sense as is the

case with a traditional comparative analysis in which the main question is normally a 'howquestion'.

43

My translation.

My translation.

45 Ibid. p. 189.

46 My translation.

47 My translation.

48 Ibid. p. 188.

49 Boele-Woelki, Katharina. 2009. Debates in Family Law around the Globe at the Dawn of the 21st Century. Antwerp – Oxford –

New York: Intersentia. p. 48.

44

17

Furthermore, based on the purpose of this study and on the selected content of the chapters

chosen to answer the main question of this thesis, both the dynamic and static strategies will be

applied in chapters 3 and 4, respectively.

Since the English and Danish legal systems each belong to separate legal traditions 50, and the rules

and provisions within the two areas under investigation deviate markedly from each other, the

Länderbericht method will be applied in subchapters 3.3 and 3.4 and in chapter 4. However,

although the legal systems differ in the two countries, the structure that I have chosen for

subchapter 3.1, that is to compare the two legal systems' approach to a number of different

criteria, makes the application of the analytical method appropriate there. Based on the above,

the analytical method is also applied in both chapters 5 and 6.

50

See sub-chapters 1.2. and 3.1 and appropriate notes. See also notes 10, 13, 14 and 15.

18

3. A historical perspective

In this chapter, an investigation of two areas, viz., the legal system in England and Denmark –

subchapter 3.1, and the historical development of the divorce law in the two countries subchapters 3.3 and 3.4, will be carried out to produce the fundamental background knowledge

deemed necessary to answer the main question put forward in this study.

The first area – the legal systems – is concerned with the origins and distinguishing criteria of the

Common law and Civil law tradition and will be treated below in 3.1. The two legal systems will be

defined from a number of different criteria that shape most legal systems. It is thus from these

criteria that the two legal systems have gained their characteristics and from which they can and

will be defined below. At the end of this subchapter, an overview table of the key distinguishing

criteria is available. Subchapter 3.2 is concerned to give a sub conclusion of subchapter 3.1.

The second area – the historical development of the divorce law in England and Denmark – has

further been divided into two parts, one for each country, namely subchapter 3.3 the historical

development of the divorce law in England, and subchapter 3.4 the historical development of the

divorce law in Denmark.

3.1

The legal systems

Grasping a concept as complex as the characteristics of a legal system is a difficult matter.

Therefore, in an attempt to give the readership a foretaste of the complexity to come, I have

chosen to begin this subchapter with a quote by Lord Cooper, an eminent Scottish judge with

insight into both the Common and Civil law tradition, in which he identifies, by way of contrast,

some of the idiosyncrasies particular to each legal tradition. Thus, according to Lord Cooper:

"A Civil law system differs from a Common law system much as rationalism differs from

empiricism or deduction from induction. The Civil law lawyer naturally reasons from

principles to instances, the Common law lawyer from instances to principles. The Civil law

lawyer puts his faith in syllogisms, the Common law lawyer in precedents; the first silently

asking himself as each new problem arises, 'What should we do this time?' and the second

asking aloud in the same situation, 'What did we do last time?'... The instinct of a Civil law

lawyer is to systematise. The working rule of the Common law lawyer is 'solvitur

ambulando'51 (to solve a problem by a practical experiment).

As may be inferred from the above, a legal tradition is not a set of rules of law about contracts,

corporations and the like, although such rules will almost always be in some sense a reflection of

51

Zweigert, Konrad. op. cit., p. 259.

19

that tradition. A legal tradition is rather a set of deeply rooted, historically conditioned attitudes

about the nature of law, that is, how it should be made, applied, studied, exercised and taught52.

As mentioned in the introduction, Common law is the legal tradition that traces its origins back to

England in 1066, and to which the current English legal system adheres. Civil law, also called the

Romano-Germanic or European Continental law, is the legal tradition to which the Danish law

system is said to belong.

Despite the clear distinction that will follow below of the characteristics of the Common and Civil

law traditions, it should be mentioned that, at certain moments in time, both legal traditions have

influenced each other more or less. Although Canon law had an influence on both traditions

during Medieval Times, its influence was more distinct on the Common law tradition.

Furthermore, the Danish legal system was much more inspired by the particular German Civil law

tradition's elements of systematism and clear terminology than was the Common law tradition53.

3.1.1 Acceptance54 of the Civil law tradition

3.1.1.1 Common law tradition

From the very beginning, Common law was considered the pride of the English courts in London 55.

Common law had been developed in the hands of medieval judges who had travelled around the

country to establish customs and who were considered the servants of the Crown of England. But

around the 17th century, the courts detached themselves from the Crown, and they became an

independent institution ranking in many ways above both the English Parliament and the Crown.

With their independence thus being solidly manifested, it is hard to overestimate the strong

position that the English courts came to hold56.

If we go back to the French Revolution, one of its important consequences was the desire of many

Continental European countries to create a nation-state. But since the French Revolution only had

an evolutionary impact on England57, the country did not seem to have this need. England's

geographical position and the Englishman's traditional respect for law58 might have played a role

in the rejection of this need for a nation-state59. Instead, England saw its own Common law as a

positive force in the emergence of England. Common law was accepted and even glorified – and

52

Merryman, John Henry. op. cit., p. 2.

Tamm, Ditlev. 2009. op. cit., p. 78.

54 Merryman talks about 'Reception', Sundberg about 'Inspiration' of the Civil law tradition. Merryman, John Henry. op. cit., pp. 1012, and Sundberg, J.W.F. op. cit., p. 186.

55 Ibid. p. 194.

56 Ibid.

57 Merryman, John Henry. op. cit., p. 21.

58 Barker, David and Padfield, Colin. op. cit., p. 5.

59 Merryman, John Henry. op. cit., p. 21.

53

20

the English saw no need for codification60 to the extent that was seen among Civil law countries61.

In England, the fear of judicial lawmaking and of judicial interference in administration did hardly

exist and as a consequence, nor the need for a clear separation of governmental powers 62.

Another peculiarity of the Common law tradition was the English legal terminology. It was quite

unique as it was based on what is called Law French or Norman French. It was applied in the courtroom only and difficult to understand, and was in itself a factor that complicated things and made

Common law a closed system and comprehensible only to the adepts, and in that way nonreceptive to external influence63.

3.1.1.2 Civil law tradition

In countries based on the Civil law tradition, the fundamental thinking was that the separation of

governmental powers was very important. Therefore, immediately after the French Revolution the

judiciary was seen as a primary target of attack; a clear distinction between the legislative and the

executive, on the one hand, and the judiciary, on the other, was considered especially important

in order to avoid the abuse of power that was possible if no clear separation between making the

law and applying it was made64. The intellectual thinking that was a product of the French

Revolution had important consequences for the systematic and pragmatic organisation and

administration of the legal systems of Civil law countries as well as for their rules of substantive

and procedural law65. The creation of nation-states that took place among many Continental

European countries seemed to require a rejection of the old legal order and a vision of a world

properly organised with a view to legal matters. In Denmark, as in many other Continental

European countries, this was materialised in a hierarchical order of the legal sources with a written

constitution, the Danish Constitution of 184966 (Grundloven af 1849), prevailing over all other

legislation. Only the state had lawmaking power and only statutes enacted by the legislative

power could be law. Therefore, it was natural that new legal systems were codified 67. Although

Denmark to a very large extent did accept and receive most principles behind the main direction

of the Civil law tradition, Denmark did differ in some ways namely in that legal university studies

were not introduced in Denmark until the mid-18th century, which may explain the undogmatic

approach to law that is seen in Denmark68.

60

The enactment of a statute incorporating all previous statute law and case law on a particular subject. Codified law is often to be

understood as written law i.e. statute law or legislation which, by the way, is also often referred to as positive law, whereas judgemade law (case law) is often referred to as non-codified law and thus unwritten law. See also note 71.

61 Merryman, John Henry. op. cit., p. 21.

62 Ibid. p. 16.

63 Tamm, Ditlev. 2009. op. cit., p. 104.

64 Merryman, John Henry. op. cit., pp. 15-16.

65 Ibid. p. 15.

66 My translation.

67 Merryman, John Henry. op. cit., p. 21.

68 Tamm, Ditlev. 2009. op. cit., p. 78.

21

Compared with the language applied in the Common law tradition, Danish law was written in

Danish from an early stage and in an easily accessible language. Furthermore, Latin was the

language used at the universities teaching Civil law, and was thus understood all over Europe,

including Denmark69. This placed Denmark along with many other Continental European countries

in a position of being far more open-minded to and receptive of Civil law ideas than was the case

in England70.

3.1.2 The sources of law and the principles behind a legal decision

3.1.2.1 Common law tradition

As mentioned under point 3.1.1, non-codifying principles lay behind the unwritten71 Common law

which had been created, throughout time, by the judges. Therefore, Common law is also often

referred to as judge-made law or case-law in contrast to statute law, legislation or positive law.

The Legal Rule72, that is to say, the principles of Common law, is to be found in and retrieved from

case-law. And the decisions made in these cases by the judges are found in law reports73.

The traditional English interpretation of legislation concentrates upon the wording of the statutes

and their very narrow interpretation74. The reason for this approach is primarily to be found in the

Common law thinking, in which the decisive element of a legal decision is the facts. And it is by

comparing the facts found in several cases that the courts establish the Legal Rule. The Legal Rule

is thus closely attached to the case to which it has been applied, and therefore can only be

understood when the actual circumstances of the case are being considered. As a consequence, to

the Common law lawyer, the rule is a rule of itself only when it has been interpreted by the

courts75. The judges are thus reasoning closely from case to case and thereby building a body of

law that binds subsequent judges through the familiar Common law doctrine of stare decisis (to

stand by past decisions)76. It is often unclear exactly what the ratio decidendi (the court's reason

for its decision)77 of a preceding case covers – and, as pointed out above, often more cases must

be studied to establish the Legal Rule. This uncertainty of the ratio decidendi places the judges in a

69

Ibid. p. 104.

Merryman, John Henry. op. cit., p. 10.

71 Common law has indeed been recorded, preserved and explained in written form in law reports. The reason why it is still being

referred to as 'unwritten' law is because 'written' law is to be interpreted as enacted or codified law, and Common law rules have

not been codified to the same extent as Civil law rules. Shears, P. And Stephenson, G. op. cit., p. 6.

72 The Legal Rule consists only of what can be retrieved from the ratio decidendi i.e. the judge's reason for his decision of a case.

Ratio decidendi must be distinguished from what is called obiter dicta which means the words delivered by the judge, but which are

NOT essential to his decision. Barker, David and Padfield, Colin. op. cit., p. 23.

73 Ibid. p. 23.

74 Tamm, Ditlev. 2009. op. cit., p. 111.

75 Lando, Ole. op. cit., p. 94.

76 The doctrine of stare decisis means that the courts have the power and are obliged to base their decisions on prior decisions

declared by superior courts i.e. to decide similar cases similarly or, in other words, to use the binding force of precedent.

Merryman, John Henry. op. cit., p. 34.

77 See note 72.

70

22

very flexible position when deciding a case78. As a logical consequence, the doctrine of stare

decisis limits the scope of the Legal Rule significantly, because an English judge is, roughly

speaking, required to look back and think in practical terms every time he is to decide a case. In

Common law, certainty and flexibility are seen as competing values. Certainty is warranted in

situations in which a precedent exists. Where this is not the case, uncertainty prevails and makes

room for flexibility79.

Traditionally, English judges are critical of the interference by the legislators with the Common

law, and, as already noted, they therefore have a distinct tendency towards a narrow

interpretation of statutes80. Similarly, as a rule until recently, they were not and are still not always

allowed to include Parliament's preparatory work, the so-called Hansard81, in order to find help

and guidance whenever he has to decide a case82. Therefore, the judges demand that the

legislators express themselves clearly when writing a legal document, because the judges attach

almost all importance to the formulation of the document83, the so-called 'Literal Rule' that lays

down that words must be given their literal grammatical meaning84. For some time now, however,

English judges have adopted a more liberal attitude to the wording and pay more attention to the

purpose and intent of the legislation85.

Likewise, the ultimate legislator in England, today, is Parliament86. But although modern law in

England is predominantly legislative in origin, Common law is nevertheless a major source of law,

and many Englishmen still think of legislation as having only a kind of supplementary function to

Common law87. It has always been the fundamental rule that the English courts have been

unwilling to develop the law on the basis of written statutes and thus, have refused to extend

them by giving them a broad interpretation88. As a consequence, much law in England has still not

been codified and therefore are to be found in law reports, just as England has no written

constitution as it is also to be found in the unwritten Common law89. Therefore, Common law

thought still exerts fundamental influence in most jurisdictions in England as well as continues to

overshadow the way the English teach, write and think about law90.

78

Lando, Ole. op. cit., p. 97.

Merryman, John Henry. op. cit., p. 49.

80 Lando, Ole. op. cit., p. 92.

81 The name of the Official Report of Parliamentary Debates. The Hansard may clarify obscure and ambiguous legislation. This

prohibition against reference to Hansard is expressed in The Exclusionary Rule. In 1992, however, the House of Lords decided to

limit the use of this rule due to Britain's entry into the EU. Ibid. p. 92.

82 Ibid. p. 92.

83 Tamm, Ditlev. 2009. op. cit., p.109.

84 Barker, David and Padfield, Colin. op. cit., p. 33.

85 Lando, Ole. op. cit., p. 94.

86 Ibid. p. 92.

87 Ibid.

88 Ibid.

89 Merryman, John Henry. op. cit., pp. 24-25.

90 Cotterrell, Roger. 1989. The Politics of Jurisprudence. London and Edinburgh: Butterworths. p. 21.

79

23

3.1.2.2 Civil law tradition

In the Civil law tradition, legislation i.e. codified law, is the main source of law in most Continental

European countries, including Denmark91. Hence, the Common law doctrine of stare decisis is

obviously inconsistent with the separation of powers as formulated in Civil law countries, and is

therefore rejected by the Civil law tradition since judge-made decisions are not considered to be

law, as the function of the judge is solely to interpret and to apply 'the law' as it has been defined

by the legislators92. Although the Civil law judges do attach importance to precedents, they do not

show these the same respect as do the Common law judges93. This reluctant attitude toward

precedents has been adopted in an attempt not to stall the development of the society by

attaching an unconditionally binding effect on previous decisions94. In Denmark, judges have been

forced to look at the development of society before making a decision e.g. within the field of

divorce law95. The fundamental doctrine of the Civil law tradition thus establishes that a decision

made by Danish judges must be based on legal principles set out in statutes. In that way, a law rule

that is intended to embrace future situations is made and as a consequent formulated in general

terms. The Danish judges are thus expected to look forward and think in abstract, academic and

theoretical terms96. To understand the legislation, the judges are often required to consult the

preparatory work of a statute published by the Danish parliament (Folketinget) 97. In the Civil law

tradition, there is great emphasis on the importance of certainty in law98. Consequently, judges

are, as already mentioned, prohibited from making law as the law rule or the legal principles from

which the judges are to work should be clear, complete and coherent in the interest of certainty 99.

In this sense, the emphasis on certainty is an expression of a desire to ensure that the judges do

not interfere with the law. Hence, the discretionary power is far less exercised by the Civil law

judges compared with the Common law judges, as it is seen as a threat to certainty100.

91

Lando, Ole. op. cit., p. 91.

Merryman, John Henry. op. cit., pp. 22-23.

93 Lando, Ole. op. cit., p. 97, and Dübeck, Inger. op. cit., p. 21.

94 Lando, Ole. op. cit., p. 95.

95 Dübeck, Inger. op. cit., p. 21.

96 Lando, Ole. op. cit., p. 95.

97 Ibid. p. 94.

98 Merryman, John Henry. op. cit., p. 49.

99 Ibid. p. 48.

100 Ibid. pp. 48-49.

92

24

3.1.3 Procedure, judges and lawyers and their educational background

3.1.3.1 Common law tradition

From the beginning, the Common law procedure was built on the so-called rigid system of writs101

which was a characteristic procedural system including juries and a strict centralisation of the

royal courts in which a person has no right without a cause of action which required the existence

of a wrong102. The system, however, was abolished by the Law Reform Act 1873. This Act

constituted a decisive change of direction in English law away from procedural rights (form) to

more substantive rights (content). However, to understand the Common law system, it is

important to know that it is deeply rooted in procedural rules despite the changes103. And as

Legrand observes, the absence of a culture of right unless justified by a cause of action suffuses

the whole of English legal life104.

It is the general opinion that in the procedural system of the Common law tradition lawyers105 will

be carefully prepared for a case whereas the judges will have only a vague idea of what the issues

and testimony may be. Hence, the judges are supposed to rely on the lawyers to present all the

necessary facts. To this end, the judges take up a relatively passive position in so far as they must

learn about the case as it proceeds. The reason for giving the leading role to the parties and their

lawyers has to do with certain deeply held views about the best way to get at the truth in the

course of a court hearing namely, by use of the so-called 'adversary procedure106' that the English

Common lawyers consider as the ruling principle of procedural law, expressed very clearly in the

following statement: ' In litigation as in war'107. However, as noted in the beginning of the chapter,

it must be underlined that in matrimonial matters, the inquisitorial procedure108 is used due to the

strong influence of Canon law on the Common law tradition in Medieval England.

Since the English judges, through the doctrine of stare decisis, have the power to make new law,

their position in the legal system is central. Judges thus exercise very broad interpretative powers,

101

The system in which a legal document, a writ, was issued by a court to originate some legal actions. It was said that for every

civil wrong there was a separate writ. However, the number of writs was limited, and if the wrong writ had been chosen, the case

was lost. In addition, each writ had its own special rules of procedure. Zweigert, Konrad. op. cit., p. 185.

102 Legrand, P. (1996). European Legal Systems Are Not Converging. International and Comparative law Quarterly, (45), p. 70.

103 Tamm, Ditlev. 2009. op. cit., pp. 100 and 114.

104 Legrand, P. op. cit., p. 71.

105 Here the term covers both barristers and solicitors. England and Wales has what could be characterized as a dual or split legal

profession in relation to legal representation where two different types of lawyers are found: barristers and solicitors. Essentially,

barristers are the lawyers who represent litigants as their advocate before the courts. They speak in court and present the case

before a judge or jury. Barristers are also engaged by solicitors to provide specialist advice on points of law. Barristers are rarely

instructed by clients directly. Instead, the client's solicitor will instruct a barrister on behalf of the client. In contrast, solicitors

generally engage in preparatory work and advice, such as drafting and reviewing legal documents, dealing with and receiving

instructions from the client, preparing evidence, and managing the day-to-day administration of a case. This duality of function

between barristers and solicitors is particular to English Common law. Shears, P. And Stephenson, G. op. cit., p. 51.

106 In law, the 'adversary procedure' is one of two methods of exposing evidence in court. It requires the opposing sides to bring out

pertinent information. The other method is the 'inquisitional procedure' during which the case is under the control of the judge

whose responsibilities include the investigation of all aspects of the case. Zweigert, Konrad. op. cit., pp. 272-273. See also notes 150

and 151.

107 Ibid. pp. 272-273.

108 See note 151.

25

even where the applicable statute or administrative action is found to be legally valid. Decisions

are made by named judges, who speak as human beings, and who try to convince the public and

give reasons for their choice of precedent in an attempt to demonstrate the law's claims of

legitimacy and authority109. In the Common law world, judges are seen as an authority figure, and

the court proceeding is permeated by a moralistic flavour110. As, it is argued, legal evolution is still

largely seen the way the judge sees it, it is not surprising that a dominating position is easily given

to procedural law, because many judges have no other perspective to apply111.

Previously, the legal training of Common law judges took place in the courts - the so-called Inns of

Court112 - and only to a limited extent at universities. Today, the training is still attached to the

courts, but some kind of legal university degree is, however, presupposed. Therefore, it seems

correct to state that Common law is predominantly controlled by legal practitioners. Nevertheless,

the tradition of scholars i.e. law professors as an important force in the development of Common

law is catching on, but still very recent and relatively weak113.

3.1.3.2 Civil law tradition

By contrast, the Civil law procedure is based rather on the idea that it will be easier to get at the

truth if the judge is given a stronger role. This implies that he should be entitled to ask questions,

inform, encourage and advice the parties, the lawyers and witnesses114.

In the tradition of Civil law, the judge is something entirely different from the judge found in the

Common law system. He is a civil servant - a functionary – educated to hold positions in public

life115. According to Sundberg, with this background, the Civil law judge is inclined to view the legal

process as part of a greater societal process116. His decisions are formulated in an impersonal style

and in courts sitting with more judges, only the opinion of the majority is made official in line with

the Civil law maxim that people need to hear 'the law' which cannot speak with more than one

voice117. The image of a judge is that of an operator of the law which is designed and built by

legislators118. This means that the judge is presented with a fact situation to which a legislative

answer will normally be readily found. The judges' function is then to find the right legislative

109

Lando, Ole. op. cit., p. 98.

Merryman, John Henry. op. cit., p. 123.

111 Sundberg, Jacob. W.F. op. cit., pp. 195-196.

112 These Inns of Court are of medieval origin. They were established by jurists who organised themselves in a kind of guild and

exercised very great political influence. The future lawyer learnt his law by practical and empirical training taught during lectures

given by more experienced practitioners. Zweigert, Konrad. op. cit., p. 191.

113 Merryman, John Henry. op. cit., p. 57.

114 Zweigert, Konrad. op. cit., p. 273.

115 Merryman, John Henry. op. cit., p. 35.

116 Sundberg, Jacob. W.F. op. cit., p. 193.

117 Lando, Ole. op. cit., p. 98.

118 Merryman, John Henry. op. cit., p. 36.

110

26

provision, connect it with the fact situation, and approve the solution that is more or less

automatically produced from this connection119.

Contrary to the Common law tradition, the great names of the Civil law are not those of judges,

but those of legislators120. The Civil law is the law of professors, and the statutes are expressed in a

considerably clearer, more comprehensible, and shorter form than those prepared in the English

Common law system. The Civil law lawyer approaches legislation broadly, looks at the intent,

purpose or scheme of it121 and attach far more importance to substantive rules i.e. rights and

obligations than to procedural rules122.

119

Ibid. p. 36.

Ibid.

121 Shears, P. And Stephenson, G. op. cit., p. 13.

122 Lando, Ole. op. cit., p. 99.

120

27

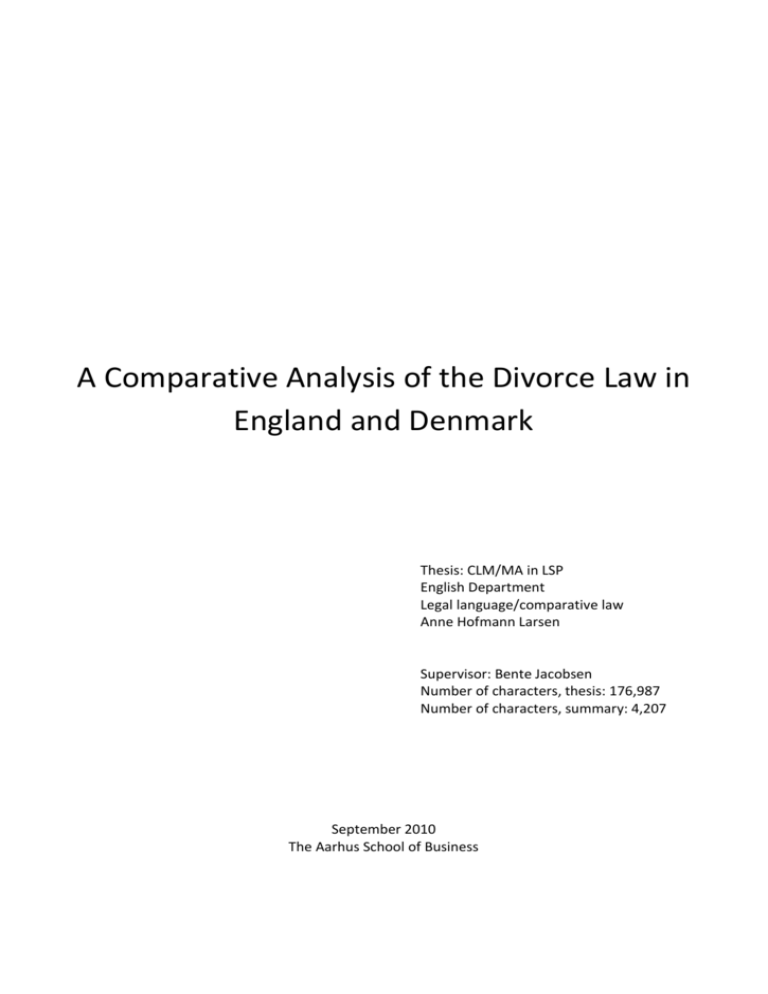

Table 3.1 Overview table of the distinguishing criteria characterising the Common and Civil law

tradition123

Common law

Civil law

Character of the law

Pragmatic/forensic and unsystematic

Academic/theoretical and systematic

Legal principles to be found in

Law reports

Textbooks/Legislation

Character of court-room practice

'Adversary' ('inquisitorial' in family matters)

'Inquisitorial'

Educational background of judges

Practical (in the courts)

Academic (at universities)

Constitution

Unwritten

Written

The law is mainly built up by

Case-law

Legislation

Law-making power lies to a large extent with

Judges

The State/Legislators

Image of the judge

Authoritative figure

Civil servant/Functionary

Formulation of Statute law/Legislation

Complex, long and exact

Short, complete and clear

Accessibility of legal principles

Difficult

Easy

Procedural law

High

Low

Substantive law

Low

High

Wording of legal text

High

Low

Rule of Precedent

High

Low

Role of judges

High

Low

Codification

Low

High

Certainty in law

Low (as certainty competes with flexibility)

High

Discretionary power of judges

High

Low

Degree of importance attached to:

123

My production.

28

3.2

Sub conclusion

From the discussion in subchapter 3.1, it seems obvious that the Common and Civil law traditions

have departed and developed from very different platforms. Contrary to the Civil law tradition, in

the Common law tradition, law is primarily judge-made, the rule of precedent is prevalent, and the

judges have broad interpretative and discretionary power, possess a moralistic attitude and a

central position in the legal system for example.

On the other hand, what also seems to be obvious is that the two traditions have converged to

some degree in a number of fields e.g. within the field of precedent. According to Merryman, it is

a well-known fact that Civil law judges do use precedents where statutes are too broadly

formulated just as it is well-known that Common law judges distinguish cases they do not want to

follow, and sometimes overrule their own decisions where these would produce a result in conflict

with prevailing social circumstances or the public order124. Another example can be found within

the field of codification in which the Common law tradition, for some time, has recognised the

need to bring the judge-made rules into a systematic order by way of scholarly discussion and

legislative action to make the rules easier to understand.