a primer on injunctive relief in federal and state

advertisement

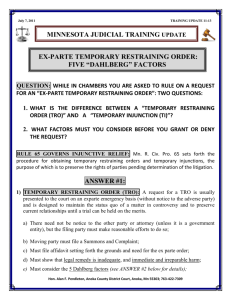

A PRIMER ON INJUNCTIVE RELIEF IN FEDERAL AND STATE COURT BY WILLIAM FRANK CARROLL AND RICHARD M. HUNT INJUNCTIVE RELIEF IS AN EQUITABLE REMEDY finding its genesis in the power of the English chancellor to relieve litigants from the strictures of the law as applied by the law courts. The remedial power was so undefined and unlimited that it was said to be determined by “the length of the chancellor’s foot.” Today injunctive relief in the federal and state courts is much more strictly circumscribed by statute, rule, and governing case law. Nevertheless, injunctive relief retains its ability to do that which is beyond the strict limitations of the law. A suit for injunctive relief is one of the most effective tools available to a litigator, especially when a request for immediate relief is included. At the same time, suits seeking injunctive relief are almost always extraordinarily expensive, and make unusual demands on the lawyers and clients on both sides. This paper will discuss the mechanics of obtaining injunctive relief as well as the strategic considerations that must inform the decision to seek such relief. I. Injunctive Relief in Federal Court A. Introduction Two primary forms of preliminary injunctive relief are available in federal court, temporary restraining orders and 1 preliminary injunctions. Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 65 outlines the general standards for obtaining injunctive relief; however one must look to other federal rules, local court rules, and case law for the procedural and substantive 2 law applicable to injunctive relief. B. Temporary Restraining Orders 1. Generally Most courts, and particularly the federal courts, are reluctant to issue temporary restraining orders because they have substantial impact on the case but are determined on an incomplete record, without oral testimony and often on an 3 ex parte basis. 2. Pleading and Notice Requirements The complaint seeking the temporary restraining order must be verified or 4 supported by affidavit testimony. In addition, the complaint must demonstrate by “specific facts” that “immediate and irreparable injury, loss or damage” will result to the applicant before the adverse party can be heard 5 in opposition. It is most important that the complaint establish facts through persons with personal knowledge, of irreparable harm. Unlike some courts, federal courts do not generally grant temporary restraining orders based upon conclusions (the foreclosure would be wrongful) or questionable testimony. The applicant’s attorney must also certify to the court in writing as to the efforts which have been made to give notice to the opposing party and the reasons supporting 6 why such notice should not be required. 3. Substantive Showing The Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals has delineated a generally accepted four prong test which must be satisfied in order to obtain a temporary restraining order. The applicant must establish each of the following: “(1) a substantial likelihood of success on the merits; (2) a substantial threat that failure to grant the injunction will result in irreparable injury; (3) that the threatened injury outweighs any damage that the injunction may cause the opposing party; and (4) that the injunction 7 will not disserve the public interest. Thus the federal test requires a balancing of the injury to be suffered by both parties, not just by applicant. Also, the court is required to consider the impact the injunction will have on “the public interest,” even in suits between private 8 parties. 4. Duration A temporary restraining order issued without notice may not exceed 10 days in duration unless “for good cause shown” the order is extended “for a like period” or unless the party against whom the order is entered 9 “consents that it may be extended for a longer period.” If the temporary restraining order is extended, the reasons for 10 any extension of time must be entered of record. 5. Terms of the Order and Filing Because of the extraordinary nature of injunctive relief, the temporary restraining order must contain specified findings and information. The temporary restraining order must: (1) be endorsed with the date and hour of issuance; (2) define the injury and state why it is irreparable; (3) state why it was issued without notice; (4) specify that it expires within 10 days after entry; and (5) be filed “forthwith” in the clerk’s 11 office and entered of record. In addition the temporary restraining order must (1) set forth the reasons for its issuance; (2) be specific in terms; and (3) shall describe in reasonable detail, without reference to the complaint or other document, the act or 12 acts sought to be restrained. 6. Security The party obtaining the temporary restraining order must give security in whatever sum the court deems proper for the payment of costs and damages “as may be incurred or suffered by a party who is found to have been 13 wrongfully enjoined or restrained.” 7. Conference With Court In Texas state court practice the applicant’s attorney generally has the opportunity to present the temporary restraining order request to the judge on an ex parte basis. This almost universal state court practice is not prevalent in federal court. Depending upon the predilections of the particular judge, the applicant’s request may be decided on the papers, or at best, after the attorney has had a brief conference with the judge’s law 14 clerk. Consequently, it is especially important when seeking a temporary restraining order in federal court that the papers clearly demonstrate the need for and entitlement to relief without benefit of counsel’s presentation. 8. Service of Temporary Restraining Order A temporary restraining order must be formally served, which is traditionally done with the service of the complaint. Any person who is not a party and is of 18 years of age may serve the temporary restraining order, including someone 15 appointed by the court for that purpose. The person serving the temporary restraining order is then required to 16 file a proof of service with the court. 9. Persons Bound by Temporary Restraining Order The person or entity named as the defendant is bound by the terms of the temporary restraining order. However, additional actors are also subject to the restraints of the temporary restraining order. It binds the parties and “their 17 officers, agents, servants, employees and attorneys.” Further, it is binding upon those persons “in active concert or participation with them who receive actual notice of the 18 order by personal service or otherwise. Therefore, if service is for any reason delayed, it is important to give notice of the issuance of the temporary restraining orderincluding a copy of the same-to the opposing party and those acting in concert with that party. 10. Hearing on Preliminary Injunction if Temporary Restraining Order Granted If a temporary restraining order is granted without notice, the court must set a hearing on the preliminary injunction at “the earliest possible time,” which may not exceed 10 days with one extension for good 19 cause shown. A party against whom a temporary restraining order is granted without notice may move on 2 days notice for a hearing to dissolve or modify the order and the court will hear such motion “as expeditiously as the 20 ends of justice require.” 11. Strategy on Temporary Restraining Orders in Federal Court Given the general reluctance of the federal courts to grant ex parte temporary restraining orders, it is imperative that careful consideration be given to whether a temporary restraining order should even be requested. If the basis for liability is less than clear or the nature of the irreparable injury suspect, caution should be exercised in seeking a temporary restraining order. Consideration should rather be given to requesting an expedited hearing on a preliminary injunction. The second factor to consider is whether the client can post the required bond. Unlike some courts, the federal courts rarely permit posting of nominal bonds to secure substantive injunctions ($500.00 foreclosure on $l million home). bond to present The third factor to consider is whether there is any real advantage to filing suit in federal court for such temporary relief. Of course, in some instances the federal courts have exclusive jurisdiction and the application must be filed in 21 that forum. Absent such limitation, it will often be easier to obtain ex parte injunctive relief in the state court system. Finally, make sure that the federal court has an independent 22 basis for federal subject matter jurisdiction and that venue 23 is proper in the district in which the suit will be filed. 12. Checklist for Federal Court Temporary Restraining Orders a) Determine jurisdiction and venue. b) Decide whether standards are satisfied for temporary restraining order. c) Prepare complaint and application for temporary restraining order. d) Select witness(es) to verify complaint or provide affidavit testimony supporting the temporary restraining order application. e) Prepare brief in support of your application. Although this is not required, generally it will be very helpful in those cases where there is any legal issue as to entitlement to relief or where there is no opportunity to visit with the judge to supplement the written presentation. f) Arrange for bond or posting of cash security with the district clerk once the temporary restraining order has been signed. If a bond is to be utilized, arrangements should be made in advance. g) Arrange for service/notice to all impacted parties. This might include filing an application and order for appointment of someone to serve process and the temporary restraining order at the time the complaint is filed. h) Consider filing a motion for expedited discoverybut be reasonable. Asking the court to order the production of 40 categories of documents in 5 days and to present 10 witnesses for deposition is not only unlikely to be granted, but is also unlikely to enhance your credibility with the court. i) Review the local rules to determine any special procedures or requirements for obtaining a temporary restraining order. preliminary injunction may be dissolved or may be made permanent depending upon the form and scope of relief required by the final judgment. j) Check with the district cleric (if you do not practice in the district or in federal court generally) to determine how such filings are handled and what is done if the judge to whom the matter is assigned is not available. Unlike some courts, it would be the most unusual of cases if you were allowed to pick up your file and wander from court to court until you could find a judge who was available to consider the application. 5. Terms of the Preliminary Injunction A preliminary 30 injunction must set forth the reasons for its issuance. The order must be specific in its terms and must describe in reasonable detail (and not by reference to the complaint or 31 other document) the act(s) to be restrained. Although Rule 65(d) does not so require, it is advisable for the order to set forth the specific equitable findings which justify the 32 issuance of a common law injunction. Thus the order should clearly describe why the injunction is necessary to prevent irreparable harm, the reasons the applicant is likely to prevail on the merits, and a balancing of the parties’ and 33 the public’s interest in having the injunction granted. k) Prepare a detailed order granting the relief requested-but be reasonable. Requesting to enjoin a national bank from disposing of “all documents relating to its check cashing policies since 1980” is not likely to find favor with most federal judges. l) Determine if the district clerk expects you to prepare the writ of injunction or whether they have a form available. m) Be sure you have checks for all applicable filing fees. n) The attorney should “hand walk” the filing through the district clerk’s office and then take the file marked judge’s copies to the judge’s secretary or administrative assistant. o) If the temporary restraining order is granted, promptly post the bond and effect service/notice as applicable. C. Preliminary Injunctions 1. Generally The purpose of a preliminary injunction is to preserve the status quo pending 24 a final decision on the merits of the case. The status quo is “the last peaceable uncontested status” prior to the parties 25 present disagreement. 2. Pleading and Notice Requirements A complaint seeking a preliminary injunction is subject to the same pleading requirements generally applicable in federal 26 court. There is no requirement that the complaint be verified. However, sworn proof establishing entitlement to relief must be submitted before a preliminary injunction will be granted. The normal procedure for seeking a preliminary injunction is by motion or by an order to show cause, the former being preferred. Unlike a temporary restraining order, a preliminary injunction may not be granted without notice to the adverse 27 party. 3. Substantive Showing The substantive requirements for obtaining a preliminary injunction are the same as for 28 obtaining a temporary restraining order. The court will again perform a balancing of interests test assessing the impact of granting the requested relief on the respective 29 parties and on the public interest. 4. Duration The preliminary injunction remains in effect, unless dissolved or modified, during the pendency of the litigation. When the case is decided on the merits the 6. Security The successful applicant for a preliminary injunction is required to post security in the same manner 34 as for a temporary restraining order. 7. Person’s Bound By Preliminary Injunction The same broad category of persons are bound by a preliminary injunction as are those subject to a temporary restraining order. The same procedure discussed previously with respect to service and notice of a temporary restraining order should be followed with respect to a preliminary 35 injunction. 8. Hearing on Preliminary Injunction Before granting a preliminary injunction the opposing party must be given 36 notice and an opportunity to be heard. However, it is not necessary for the court to hold an evidentiary hearing where 37 the parties are allowed to present testimony. A hearing 38 may be required if there is a material factual dispute; however, some courts have upheld the denial of a hearing 39 even when the facts are controverted. In fact it is the standard practice of some federal judges to resolve all preliminary injunction applications without an oral 40 hearing. Evidence at a hearing on a preliminary injunction may include verified pleadings, affidavits, deposition testimony, documentary evidence and oral testimony. Because the function of a preliminary injunction is to maintain the status quo rather than adjudicate the matter on the merits, the federal courts are more lenient in demanding strict compliance with the rules of evidence. Consequently, affidavits are not held to the strict requirements of those 41 supporting summary judgment and hearsay evidence may 42 be considered by the court. It should be noted that the court may, before or after commencement of any hearing on a preliminary injunction, order that the hearing be consolidated with the trial on the 43 merits. Even if a consolidation is not ordered, any evidence introduced at the preliminary injunction hearing becomes a part of the final trial record if it would have been 44 admissible in a trial on the merits. Counsel should, however, be cautious in relying on this rule if essential testimony is included in affidavits or depositions, if it would be inadmissible at trial because it is not based on personal knowledge, is conclusory, or is hearsay. 9. Checklist for Preliminary Injunctions In addition to the items suggested with respect to a temporary restraining order, several additional matters are worth considering, particularly if no oral hearing is permitted. a) Prepare a brief in support of your motion. Although this may not always be required by local rules generally it will be very helpful in those cases where there is any legal issue as to entitlement to relief or where there is no opportunity to supplement the written presentation with testimony and arguments. b) Carefully filter the evidence to be presented in support of the application. To the extent possible the affidavits should comply with Fed.R.Civ.P.56(e). Also, limit the amount of deposition testimony-highlighted-submitted to the court. Also, limit the amount of documentary evidencehighlighted-submitted to the court. c) Include all of the evidence in a clearly organized, readable appendix. d) If the case justifies it, and the client can afford it, provide the court with a CD-ROM of your brief with links to case citations, statutes, affidavits, documents and evidentiary testimony. On critical factual issues, video taped excerpts should also be included. This allows the court to consider the demeanor of the witness without an oral hearing. e) Prepare a detailed order making all of the findings of fact and conclusions of law necessary to support injunctive relief. If possible, provide the same to the court in a CDROM as well as a hard copy. f) Arrange for a new bond to be posted since the terms of the old bond will probably be confined to the temporary restraining order. D. Equitable Defenses The party opposing an application for a temporary restraining order or a preliminary injunction has the full range of legal defenses available to the asserted claim for relief, even if injunctive relief is also requested, These defenses are considered under the first prong of the four prong test for granting injunctive relief-is the applicant likely to succeed on the merits. Consequently, it is a defense to injunctive relief if the applicant’s claim is barred by limitations, the contract sued on is void on its face, or the applicant has no standing to bring suit. However, because the relief being sought is equitable and discretionary, there are other defenses to an application for 45 injunctive relief which are based on a fairness concept. Examples of such equitable defenses include: 46 1. Applicant acted in bad faith; 2. Applicant has unclean 47 48 49 hands; 3. Applicant has failed to do equity; 4. Laches; 50 and 5. Waiver. E. Limitations on Federal Jurisdiction to Grant Injunctions Although federal courts have the power to grant injunctions in cases in which they have subject matter jurisdiction, Congress has circumscribed that power in three specific areas. The Federal Anti-Injunction Act prohibits a federal court from enjoining pending state court proceedings unless 1) it is specifically authorized by an Act of Congress; 2) where necessary in aid of its jurisdiction; or 3) to protect or 51 effectuate its judgments. The first exception is for those Acts of Congress which authorize issuance of an injunction. Examples include the Federal Interpleader Statute which specifically authorizes the issuance of an injunction to restrain the institution of 52 “any proceeding in any state...court.” Likewise, in a habeus corpus action the court may enjoin any proceeding 53 “against the person detained in any state court,” Other 54 examples include the removal statute and the Bankruptcy 55 Act. The second exception is where the injunction is necessary in aid of the court’s jurisdiction. Although of limited application, this exception is most often invoked to enjoin a subsequent state court suit involving property which is in 56 the custody of the federal court. The final exception permits the federal court to enjoin a state court proceeding in order to protect or effectuate its judgments. This exception is often referred to as the “relitigation exception.” It is founded on the doctrines of res judicata and collateral estoppel and “insulates from litigation in state proceedings” those matters which 57 “actually have been decided by the federal court.” Two other statutes also limit a federal court’s power to issue injunctions. The Tax Injunction Act prohibits the federal court from enjoining “the assessment, levy or collection of any tax under state law;” if a “plain, speedy 58 and efficient remedy” is available in the state courts. The Johnson Act prohibits the enjoining of rates charged by a public utility if such rates are established by a state administrative or rate-making body, if the case is based on diversity jurisdiction, and if other requirements are 59 satisfied. F. Appellate Review of Orders Granting Injunctive Relief Congress has by statute authorized immediate review of “interlocutory orders of the district courts...granting, continuing, modifying, refusing or dissolving an injunction or refusing to dissolve or modify an injunction, except where direct review may be had in the 60 Supreme Court;...” Appeals may be taken both from orders granting .61 preliminary as well as permanent injunctions The appeal is as of right, and is not subject to the discretion of either 62 the trial or appellate court. Temporary restraining orders, however, are not 63 appealable. The fact that the order is titled a temporary restraining order will not preclude an appeal if it is in fact 64 more than a temporary restraining order. Likewise, an order need not specifically deny an injunction to be appealable. If the practical effect of the order is a 65 denial of injunctive relief, then it is appealable. Finally, a refusal to act on an application for injunctive relief will not preclude appellate review. The refusal to rule will be deemed to be a denial of the injunction thereby permitting 66 the order to be appealed. II. Injunctive Relief in Texas State Courts A. Introduction In most cases, a suit for injunctive relief begins with a request for a Temporary Restraining Order, followed by a request for a Temporary Injunction, followed by a permanent injunction that is part of the final judgment in a case. The Temporary Restraining Order may be issued with or without notice to the opposing party but can remain 67 in effect only a short time. The Temporary Injunction is issued after an evidentiary hearing that amounts to a minitrial of the case. It remains in effect until the entry of a final judgment. The permanent injunction is issued after trial. The two preliminary steps to permanent relief — temporary restraining order and temporary injunction — build on the standard for granting a permanent injunction, with the first two steps requiring additional evidence to justify the demand for relief before trial. A permanent injunction can issue after trial if the claim is one for which injunctive relief is appropriate. A temporary injunction can issue after an evidentiary hearing if the claim is one for which injunctive relief is appropriate and the moving party has shown that it is substantially likely to prevail at trial and that it will suffer irreparable harm before trial unless the 68 injunction is granted. A temporary restraining order can be issued only if all the requirements for a temporary injunction are satisfied and the threat of harm is so immediate that it will occur before the Court even has time to conduct an evidentiary hearing. In addition, most state courts require evidence that the party moving for a temporary restraining order have attempted to contact opposing counsel so that there is at least a non-evidentiary hearing before the temporary restraining order is granted. In general, the more immediate the relief sought, the greater the burden on the party seeking relief to demonstrate that there is a real risk of immediate harm and that it will prevail in the end. B. Substantive Requirements for Granting Injunctive Relief Before and at Trial Consideration of a claim for injunctive relief must begin with the substantive requirements for such relief. Injunctions are not available to stop every kind of harm, and every claim for such relief requires pleading an appropriate cause of action. 1. Claims for Which Permanent Injunctive Relief is Available Injunctive relief, like every other form of equitable relief, is generally available when there is no “adequate remedy at law;” that is, when money damages are not adequate. This requirement has been codified in Section 65.011 of the Texas Civil Practice & Remedies Code, which provides: A writ of injunction may be granted if: (a) the applicant is entitled to the relief demanded and all or part of the relief requires the restraint of some act prejudicial to the applicant; (b) a party performs or is about to perform or is procuring or allowing the performance of an act relating to the subject of pending litigation, in violation of the rights of the applicant, and the act would tend to render the judgment in that litigation ineffectual; (c) the applicant is entitled to a writ of injunction under the principles of equity and the statutes of this state relating to injunctions; (d) a cloud would be placed on the title of real property being sold under an execution against a party having no interest in the real property subject to execution at the time of sale, irrespective of any remedy at law; or (e) irreparable injury to real or personal property is threatened, irrespective of any remedy at law. Various other statutes may expand or qualify the general provisions of Section 65.011, and one of the first steps in analyzing a possible claim for injunctive relief is to review possibly applicable statutes to see if they grant a right to or limit injunctive relief. Creative lawyers should not, however, consider themselves limited to specific statutes or even circumstances considered by courts in the past. If an award of money damages will not adequately compensate the anticipated future harm then injunctive relief should be available. 2. Additional Substantive Requirements for the Granting of a Temporary Injunction The purpose of a temporary injunction is to preserve the status quo of the litigation’s subject matter pending a trial on the merits. Butnaru v. Ford Motor Co., 84 S.W.3d 198, 204 (Tex. 2002). Status quo is defined by the Texas Supreme Court as “the last, actual, peaceable, non-contested status that 69 preceded the pending controversy.” In almost every case where permanent injunctive relief is available, a temporary injunction will also be available in theory, because the acts that are sought to be enjoined will usually cause harm — a change in the status quo — before there can be a final trial. However, the requirement of imminent harm is not trivial, and regardless of the validity of the claim proof of imminent harm will be required for a temporary injunction. a) There must be an imminent threat of harm. Because a temporary injunction is issued before there is an opportunity for complete discovery and development of the case, its issuance requires more than a theoretical risk of harm before trial. The Texas Supreme Court requires proof of “a probable, imminent, and irreparable injury” in the period before trial. Butnaru, supra. In EMSL Analytical, Inc. v. Younker, 154 S.W.2d 693 (Tex.App. — Houston 2004, no writ) the Houston Court of Appeals affirmed the denial of a temporary injunction because the plaintiff had only shown a “theoretical possibility” of future harm. It wrote that: At most, the testimony of EMSL’s regional manager established only a fear of possible injury, and that contingency is not sufficient to support issuance of a temporary injunction.” Id. at 697. A party seeking a temporary injunction should develop evidence of actual, as opposed to theoretical harm, and a party resisting an injunction may find that denying any intent to engage in forbidden conduct is an effective defense. b) The movant must show a probable right to final relief after trial. A party seeking a temporary injunction must not only plead a cause of action justifying injunctive relief; it 70 must also prove a “a probable right to the relief sought.” This does not mean proof that would result in victory at a final trial, but is something more than presentation of a 71 prima facie case. Appellate review of the grant or denial of a temporary injunction is based on an abuse of discretion standard, and so as a practical matter the trial court’s decision to grant or deny an injunction will be affirmed if there is evidence from which a reasonable person would 72 reach the same conclusion as the trial court. 3. The Additional Requirement of Immediate Harm for Issuance of a Temporary Restraining Order Temporary restraining orders are governed by Texas Rule of Civil Procedure 680, which requires a showing that: “immediate and irreparable injury, loss or damage will result to the applicant before notice can be served and a hearing had 73 thereon.” A temporary restraining order can remain in effect for an initial period of only 14 days, and can be 74 extended for only an additional 14 days, which means that any hearing on the follow up request for a temporary injunction must take place within 28 days. Thus, the requirement of “immediate” injury means injury within that 28 day period. To justify relief without notice the injury must be even more immediate, and occur “before notice can be served.” C. The Process for Obtaining Injunctive Relief The process of obtaining injunctive relief begins with the filing of a Petition, application for a Temporary Restraining Order (if desired) and application for a Temporary Injunction (if desired). If a temporary restraining order is requested, the motion will be presented to the Court at the time of filing, or within a short time thereafter. It may be presented ex parte and without notice, subject to limits imposed by local rules or the Court, When the application for temporary restraining order is presented the Court will either grant or deny the temporary restraining order and set a date for a hearing on the application for temporary injunction. That hearing, which is evidentiary, ordinarily takes place within 28 days, and will result in the grant or denial of the temporary injunction. After the temporary injunction hearing the case proceeds to trial in the ordinary fashion. This broad outline of the injunction process is subject to a number of qualifications, which are discussed in detail in the sections below. 1. The Initial Papers Seeking Injunctive Relief Like any other lawsuit, a suit requesting injunctive relief is 75 commenced by filing a petition. If a temporary restraining order or temporary injunction is sought they are ordinarily included as part of the same document, although this is not required by Rule 680, which specifically governs temporary restraining orders, or by Rule 682; which governs all pleadings and motions seeking injunctive relief. The petition must be verified and contain “a plain and 76 intelligible statement of the grounds for such relief.” If a temporary restraining order is requested the pleading must go further and include sworn “specific facts” showing that “immediate and irreparable injury, loss or damage will result to the applicant before notice can be served and a 77 hearing had thereon.” A request for a temporary restraining order must be accompanied by a request for a temporary injunction, because Rule 680 requires that if a temporary restraining order is granted a hearing on the request for temporary injunction must be set as well. Most Courts require, as part of the request for temporary restraining order, a certificate to the effect that the attorney presenting the motion has made a reasonable effort to 78 notify the opposing party that the request is being filed. Individual judges often have very different views of the benefits and desirability of notice for a temporary restraining order, and before filing a request for a temporary restraining order the attorney filing it should determine what the judge requires. Because every temporary restraining order is followed in a very short time by an evidentiary hearing on the temporary injunction, requests for temporary restraining orders are usually accompanied by an Emergency Motion for Expedited Discovery under Rule 191.1 that asks the Court to order document production, depositions, and written discovery on an expedited basis. 2. What Happens at the Courthouse When a TRO is Requested Rule 685 anticipates that a request for a temporary restraining order or temporary injunction will be presented to the Court before they are filed with the clerk of the Court; however, the usual practice if the request is presented during business hours is to first file the Petition with the clerk and then present to the Court along with a proposed form of Order. In some counties all temporary 79 restraining orders are assigned to a single judge. In most counties the temporary restraining order will be considered by the judge to whose court the case is assigned; however, if the judge of the assigned Court is not available, the request may be presented to a non-resident judge under the circumstances described in Section 65.022 of the Texas Civil Practice & Remedies Code. In larger counties, the procedure for approaching other courts other than, the assigned court will probably be subject to local rules 80 specifying the procedure. Whether the petition is filed before or after presentation to the Court, once the temporary restraining order is signed, the Order and file are turned over to the clerk of the court, who prepares a citation to the defendant along with a writ of injunction that repeats the contents of the order signed by the judge. The citation and writ may be served like other citations under the provisions of Rules 103 and 106. The duties of the officer serving a writ of injunction are slightly 81 different from those of an officer serving an ordinary citation, but as a practical matter the party seeking relief will want to take whatever steps are needed to insure that the restrained party gets notice of the Order as soon as possible so that violations of the order can be punished by 82 contempt. 3. Contents of the Order Granting a Temporary or Permanent Injunction and the Parallel Writ of Injunction All orders granting an injunction, whether permanent or temporary, must: set forth the reasons for its issuance, be specific in terms, and describe in reasonable detail and not by reference to the complaint or other document the act or acts sought to be 83 restrained. In addition, an order granting a temporary injunction must: include an order setting the cause for trial on the merits with respect to the ultimate relief 84 sought , and fix the amount of security (i.e., a bond) to be given by 85 the party applying for the temporary injunction. An order granting a temporary restraining order has the same requirements as an order granting a temporary injunction except that instead of a trial date it must state the date of the hearing on temporary injunction. In addition, if it is granted without notice, the order granting temporary restraining order must: be endorsed with the date and hour of issuance, define the injury and state why it is irreparable, state why the order was granted without notice, and expire by its terms within such time as the court fixes, 86 not to exceed fourteen days. The writ of injunction issued by the clerk and served on the enjoined party generally contains the same information as the order granting the injunction except that there is no requirement that the writ include the various findings justifying issuance of the injunction that must be in the 87 order itself. 4. The Requirement of a Bond Every order granting a temporary restraining order or temporary injunction must include a requirement that the party seeking the injunction provide a bond, and that bond must be filed with the clerk 88 before the writ of injunction will be issued. The amount of the bond is fixed by the Court, and should be sufficient to compensate the enjoined party for any damage it will suffer 89 as a result of the injunction. The bond secures payment of those damages in case it is found that the injunction should not have been issued. 5. The Defendant’s Answer The defendant’s deadline to file an answer is the same as in any other case; however, because the defendant will ordinarily seek other relief related to the temporary restraining order, the answer will usually be filed very shortly after the temporary restraining order is issued. Defendants who wish to challenge personal jurisdiction by making a special appearance under Rule 120a may find it difficult to avoid unintentionally making a general appearance given the levels of activity between the issuance of a temporary restraining order and a hearing on the request for a temporary injunction. Some decisions indicate that very limited participation in such proceedings 90 does not constitute a general appearance; however, as a practical matter the discovery and other battles that immediately follow the entry of a temporary restraining order may be difficult to manage without taking “some affirmative action by the defendant which impliedly recognizes the trial court’s personal jurisdiction over the 91 defendant.” A defendant subject to a temporary restraining order who wishes to make a special appearance should, therefore, seek the early ruling required by Rule 120a in order to avoid waiver during the run up to the temporary injunction hearing. 6. After the Temporary Restraining Order and Before the Temporary Injunction Hearing — Request for Dissolution, Mandamus, Discovery, and Mediation After a temporary restraining order is entered and served the lawsuit proceeds on several fronts simultaneously. The party enjoined may, on two days notice, seek to have the 92 temporary restraining order dissolved or modified. A 93 temporary restraining order cannot ordinarily be appealed , 94 but mandamus relief is available and may be applied for. While fighting over the continued existence of the temporary restraining order, the parties will also likely be engaged in disputes about the scope and timing of expedited discovery, and will be doing the discovery as well. Many courts will order the parties to mediation under Chapter 154 of the Texas Civil Practice & Remedies Code, and, of course, all the parties must prepare witnesses and exhibits for the temporary injunction hearing itself. In short, the period between the granting of a temporary restraining order and the hearing on the application for temporary injunction is the entire pre-trial process compressed to a period of no more than 28 days. 7. The Temporary Injunction Hearing Rule 680 requires that if a temporary restraining order is granted without notice, the request for temporary injunction must be heard “at the earliest possible date and takes precedence of all 95 matters except older matters of the same character.” In practice different judges interpret this requirement in different ways. Some actually give the hearing the highest priority while others merely try to set the hearing within the 28 day period representing the maximum time before a temporary restraining order expires. Rule 680 does not require that the Court grant any particular amount of time for the hearing, and some judges may simply refuse to set aside adequate time as a means to force the parties to negotiate an agreed extension or complete settlement. The only remedy for this kind of behavior is mandamus. At the injunction hearing the applicant for a temporary injunction must establish through competent evidence that he or she has a probable right to the requested relief and that he or she will probably suffer injury in the absence of 96 such relief. Texas courts have held that this does not mean that the applicant must establish that he or she will prevail 97 at trial on the merits, but it does require more than 98 presentation of a mere prima facie cases. This means that the decision to grant or deny a temporary injunction will be affirmed if there is sufficient evidence for a rational person 99 to reach the same conclusion as the trial court. Although the burden of proof is on the movant to establish its case, a respondent relying on affirmative defenses has the burden 100 of establishing those defenses. 8. Appeals from Orders Granting or Denying a Temporary Injunction Section 51.014 provides for an interlocutory appeal of an order granting or denying a temporary injunction. Like other interlocutory appeals, the 101 appeal of a temporary injunction is accelerated. This 102 means that the deadlines to file a notice of appeal, the 103 104 record on appeal, and briefs are all shortened. In addition, the Court of Appeals may decide the case based on a sworn and uncontroverted record provided by the trial court or parties, and may dispense with the requirement of 105 briefs. If it chooses, the Court of Appeals may act on the appeal within days by using Rule 28.3. The filing of a notice of appeal does not suspend a temporary injunction, but the injunction order can be superseded by filing a bond at the discretion of the trial 106 court. A trial court’s refusal to provide for a supersedeas bond can be reviewed by the Court of Appeals, which can also make other temporary orders to protect the parties 107 during the appeal. Only the Court of Appeals can enforce the underlying order during the appeal; however, the trial court retains jurisdiction of the rest of the case, which can proceed subject to limits on the authority of the trial court to make orders that might be inconsistent with the 108 proceedings on appeal. If the appeal is from denial of a temporary injunction the appellant may apply for injunctive relief to the Court of Appeals on the basis that it is necessary to protect its jurisdiction or keep the pending appeal from becoming moot. The application for an injunction during an appeal is governed by Rule 52 of the Texas Rules of Civil procedure, which requires the filing of new original proceeding in the Court of Appeals. 9. Enforcing Orders Granting Temporary Restraining Orders, Temporary Injunctions and Permanent Injunctions Refusal to obey an injunction of any kind is 109 punishable by contempt. The detailed procedures for filing or opposing motions for contempt are beyond the scope of this paper, but are outlined in Rule 692 itself. III. Conclusion To obtain the extraordinary remedy of injunction, the wise practitioner will insure that the pleadings, proof and relief requested conform exactly to what the statutes, rules and case law require. In few other areas is such careful preparation and attention to detail met with a more effective reward than in the arena of injunctive relief. 1 Fed. R. Civ. P. 65. Numerous federal statutes, however, contain provisions authorizing injunctive relief in specific areas. See e.g. 15 U.S.C. §4 (1994) (Sherman Act); 15 U.S.C. §25 (1994) (Clayton Act). 2 For example, Rule 65 does not provide an independent basis for federal jurisdiction. See White v. National th Football League, 41 F. 3d 402, 409 (8 Cir. 1994). 3 See generally, Granny Goose Foods, Inc. v. Brotherhood of Teamsters, Local No. 70, 415 U.S. 423 (1976). 4 Fed. R. Civ. P. 65(b). 5 Id. 6 Id. 7 Allied Mktg Group, Inc. v. CDL Mktg., Inc., 878 F.2d 806, th 809 (5 Cir. 1989). 8 Mississippi Power &Light Co. v. United Gas Pipeline, th 760 F. 2d 618, 625 (5 Cir. 1985). 9 Fed. R. Civ. P. 65(b). 10 Id. 11 Id. 12 Fed. R. Civ. P. 65(d). 13 Fed. R. Civ. P. 65(c). 14 See W. Carroll, “The Local Rules and The ‘Local’, Local th Rules,” Federal Bar Association 19 Annual Federal Civil Practice Seminar (Feb. 25, 2005) at Tab 3, App.1. 15 Fed. R. Civ. P 4(c)(2). 16 Fed. R. Civ. P. 4(1). 17 Fed. R. Civ. P. 65(d). 18 Id. 19 Fed. R. Civ. P. 65(b). 20 Id. See e.g. 15 U.S.C. §1 (Sherman Act). 22 28 U.S.C. §1331 et seq. There are innumerable other federal statutes which confer jurisdiction on the federal courts in specific instances. 15 U.S.C.§1 (Sherman Act); 15 U.S.C. §78aa (Securities Exchange Act of 1934). 23 28 U.S. §1391. Many federal statutes also contain their own specialized venue provisions. See e.g. 15 U.S.C. §22 (Clayton Act). 24 th Hollon v. Mathis Indep. Sch. Dist., 491 F.2d 92 (5 Cir. 1974). 25 th Stemple v. Board of Educ. of Prince’s County, 523 F. 2d 893, 898 (4 Cir. 1980), cert denied 450 U.S. 911 (1981). 26 See Fed. R. Civ. P. 7-11. 27 Fed. R. Civ. P. 65(a)(1). 28 See supra at notes 7-8 and accompanying text. 29 Id. 30 Fed. R. Civ. P. 65(d). 31 Id. 32 See C. Wright and A. Miller, Federal Practice and Procedure §2941 at p. 31. 33 See supra at n. 11 and accompanying text. 34 See supra at n. 13 and accompanying text. 35 See supra at notes 17-18 and accompanying text. 36 Fed. R. Civ. P. 65(a)(1). 37 st th See Campbell Soup Co. v. Giles, 47 F. 3d 467 (1 Cir. 1995); FSLIC v. Dixon, 835 F. 2d 554 (5 Cir. 1987). 38 th Four Seasons Hotels &, Resorts, B.V. v. Consorico Bark, S.A., 320 F. 3d 1205 (11 Cir. 2003). 39 th See, Stanley v. University of So. California, 13 F. 3d 1313 (9 Cir. 1994). 40 See, W. Carroll, supra, n. 14, at Tab 3, App. 1. 41 th Fed. R. Civ. P. 56(f). FSLIC v. Dixon, 835 F. 2d 554 (5 Cir. 1987); Welker v. Cicerone, 174 F. Supp, 2d 1055 (C.D. Cal. 2001). 42 th Sierra Club v. FDIC, 992 F. 2d 545 (5 Cir. 1993). 43 Fed. R. Civ. P. 65(a)(2). 44 Id. 45 See generally, C. Wright and A. Miller, Federal Practice and Procedure §2946. 46 th Original Great Am. Chocolate Chip Cookie Co. v. River Valley Cookies, Ltd., 970 F. 2d 273 (7 Cir. 1992). 47 th Kentucky Fried Chicken Corp. v. Diversified Packaging Comp., 549 F. 2d 368, 372 (5 Cir. 1977) (“the bizarre element is the facially implausible-some might say unappetizing-contention that the man whose chicken is ‘finger-licking good’ has unclean hands”). 48 C. Wright and A. Miller, Federal Practice and Procedure §2946 at 14. 49 th Kay v. Austin, 621 F. 2d 809 (6 Cir. 1980). 50 Henry I. Siegel Co. v. Koratron Co., 311 F. Supp. 697 (S.D.N.Y. 1970). 51 28 U.S.C. §2283. 52 28 U.S.C. §2361. 53 28 U.S.C. §2251. 54 th 28 U.S.C. §1446(d); Maseda v. Honda Motor Co., 861 F. 2d 1248 (11 Cir. 1988). 55 11 U.S.C. §362. 56 th Green v. Green, 259 F. 2d 229 (7 Cir. 1958). 57 Chick Kam Choo v. Exxon Corp., 486 U.S. 140, 148 (1998). 58 28 U.S.C. §1341. 59 28 U.S.C. §1342. 60 28 U.S.C. §1292(a)(1). 61 th Sherri A.D. v. Kirby, 975 F. 2d 193, 202 (5 Cir. 1992). 62 Compare 28 U.S.C. §1292(b). 63 th th In Re Champion, 895 P. 2d 490, 492 (5 Cir. 1990); Belo Broadcasting Corp. v. Clark, 654 F. 2d 423, 426 (5 Cir. 1981). 21 64 th Sampson v. Murray, 415 U.S. 61, 86-87 (1994); United States v. Bayshore Assoc., Inc., 934 F. 2d 1391 .(6 Cir. 1991). Carson v. American Brands, 450 U.S. 79 (1981). 66 rd Rolo v. General Dev. Corp., 949 F. 2d 695, 703 (3 Cir. 1991). 67 No more than 20 days in federal court (FRCP 65(b)) and 28 days in Texas state courts (TRCP 680). 68 Butnaru v. Ford Motor Co., 84 S.W.3d 198, 204 (Tex. 2002). 69 State v. Southwestern Bell Tel. Co., 526 S.W.2d 526, 528 (Tex. 1975). 70 Butnaru, supra n. 68. 71 Infra ns. 92 - 94. 72 See e.g., Tri-Star Petroleum Co. v. Tipperary Corp., 101 S.W.3d 583 (Tex.App. - El Paso 2003, no writ). In that case the trial court’s issuance of a temporary injunction was affirmed because the trial court “could have rationally determined” that the evidence supported the movant’s claims, and the court of appeals was obligated to ‘Mew the evidence in light most favorable to the trial court’s order, indulging every reasonable inference in its favor.” Id. at 587, 590. In Associated General Contractors of Texas, Inc. v. City of El Paso, 932 SW.2d 124, 126 (Tex.App. - El Paso 1996, no writ) the denial of a writ was affirmed because the evidence was conflicting, and “If conflicting evidence is presented, the appellate court must conclude that the trial court did not abuse its discretion in entering its order.” 73 TEX. R. CIV. P. 680. 74 Id. 75 TEX. R. CIV. P. 22. 76 TEX. R. CIV. P. 682. 77 TEX. R. CIV. P. 680. 78 See, e.g., Dallas County District Courts Local Rule 2.02. 79 See, e.g., Harris County District Courts Local Rule 3.5 and Bexar County District Courts Local Rule (C). 80 See, e.g., Tarrant County Local Rule 3.30(b). 81 Compare TEX. R. CIV.P. 103 and 107 to 689. 82 TEX. R. CIV. P. 683. 83 Id. 84 Id. 85 TEX. R. CIV. P. 684. 86 TEX. R. CIV. P. 680. 87 See, TEX. R. CIV. P. 687. 88 TEX. R. CIV. P. 684. 89 TEX. R. CIV. P. 684. 90 Crystalix Group Intern. Inc. v. Vitro Laser Group USA, Inc., 127 S.W.3d 425 (Tex.App. - Dallas 2004, no writ), Redwood Group, LLC v. Louiseau, 113 S.W.3d 866 (Tex.App. - Austin 2003, no writ), Turner v. Turner, 1999 WL 33659 (Tex.App. th Houston [14 Dist.] 1999). 91 Redwood Group, supra n. 90. 92 TEX. R. CIV. P. 680. 93 When the TRO acts as a temporary injunction that is, it does not set its own expiration date or provide for a later hearing, it will be treated as an appealable temporary injunction. In re Texas Natural Resource Conservation Comm’n, 85 S.W.3d 201 (Tex. 2002). 94 Id. The procedures for mandamus relief are beyond the scope of this article. 95 TEX. R. CIV. P. 680. 96 See Camp v. Shannon, 348 S.W.2d 517 (Tex. 1961); Diesel Injection Sales & Serv., Inc. v. Renfro, 619 S.W.2d 20 (Tex. Civ. App.—Corpus Christi 1981, writ ref’d n.r.e.). 97 The Texas Supreme Court has stated: “We have also said that to warrant issuance of a temporary injunction, the applicant need only show a probable right and probable injury; that the applicant is not required to establish that he will finally prevail in the litigation….” Sun Oil Co. v. Whitaker, 424 S.W.2d 216 (Tex. 1968). 98 See Deer Valley Ranch, Inc. v. Adair, 574 S.W.2d 592 (Tex. Civ. App.—San Antonio 1978, no writ). 99 See cases cited infra at n. 100. 100 Michelle Corp. v. El Paso Retailers Ass’n, Inc., 626 S.W.2d 615 (Tex.App. El Paso 1981, no writ), Lund v. Leibl, 1999 WL 546996 (Tex.App. - Austin 1999, no writ) (unpublished opinion). 65 101 TEX. R. APP. P. P. 28.1. TEX. R. APP. P. 26.1(b). 103 TEX. R. APP. P. 35.1(b). 104 TEX. R. APP. P. 38.6(a). 105 TEX. R. APP. P. 28.3. 106 TEX. R. APP. P. 29.1. 107 TEX. R. APP. P 29.2, 29.3. l08 TEX. R. APP. P. 29.4, 29.5. 109 TEX. R. APP. P. 69.2. 102