display that sometimes incorporate ram-horns but the

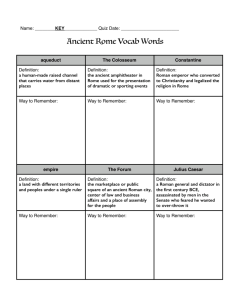

advertisement

13 Roman Art & Architecture: A work in progress CONTENTS INTRODUCTION Vitruvian Architecture Key Elements of Roman Architecture o Columns o Arches o Building Materials INFRASTRUCTURE Roads o o o o Roadworks Via Appia Via Flamina Via Sacra Bridges o Milvian Bridge, Rome o Bridge over the Tagus river at Alacantra, Spain Aqueducts & Sewers o Punic quanats o Cloaca Maxima, Rome, Italy o Hadrian’s Aqueduct, Carthage, Tunisia o Aqueduct at Segovia, Spain o Pont du Gard, Nimes, France PUBLIC BUILDINGS Temples o Greek Temple orders and styles o The Tuscan temple Rectangular Temples o Temples of Rome & Augustus at Lepcis Magna, The Capitolium of Rome & Thuburbo Majus, Tunisia o Maison Caree, Nimes, France o Temple of Bacchus at Baalbek, Lebanon Exterior Interior Round Temples o Temple of Venus at Baalbek, Lebanon, o Temples of Vesta in Tivoli and Rome, Italy o The Pantheon, Rome Exterior Interior Basilicas o Greek influences: the basiliké stoa o Vitruvian utilitarian model: Basilica at Cosa, Etruria o Pompeian Model: Pompeian basilica o Basilica Nova Maxentius Baths Roman Art & Architecture: A work in progress o o o o o o A day at the thermae Stabian Baths, Pompeii Hadrianic Baths, Lepcis Magna Baths of Caracalla, Rome Baths of Diocletian, Rome Hunting Baths, Lepcis Magna Circuses o What is a circus? o Circus Maximus, Rome Theatres o Greek influences o The Roman theatre o Theatre at Timgad o Theatre at Lepcis Magna o Theatre at Aspendos o Theatre at Sabratha o Theatre at Orange o Reconstruction of the theatre of Marcellus, Rome Amphitheatres o Gladiators o Amphitheatre at Pompeii o Amphitheatre at Nimes o The Flavian Amphitheatre, Rome TOWN PLANNING The Hippodamian Grid ITALY o Ostia: a typical roman town o Pompeii: from Oscan wool-market to Vesuvius o Aosta: a military fort o Textbook town planning in northern Italy GAUL BRITAIN NORTH AFRICA NEAR EAST FINE ART WALL PAINTING MOSAICS FREE-STANDING SCULPTURE RELIEF SCULPTURE TRIUMPHAL MONUMENTS TRIUMPHAL ARCHES TRAJAN’S COLUMN ARA PACIS DIVI AUGUSTAE ROMAN HOUSES Roman Art & Architecture: A work in progress Vitruvian architecture Picture not in Wheeler Leaonardo da Vinci’s “Vitruvian Man” showing the human body in terms of Vitruvian geometric proportionality. Vitruvius was a Roman architect active in the late 1st century BC. He was heavily influenced by Greek geometry and philosophy particularly Pythagorean aesthetics (the philosophy of Beauty) and was especially interested in the ratio of proportionality known as the Golden Mean and signified today by the Greek letter (phi). Vitruvius believed buildings should mimic nature, which in turn mimics the ideal forms of mathematics. Vitruvius studied Pythagorean philosophy and found that in all natural things from inanimate rocks to the humming hives of bees geometry abounds. He wrote a series of treatises entitled De Architectura in which he detailed how architecture should resemble life and to this end he described the ideal proportions of a man. Leonardo da Vinci famously sketched this Vitruvian Man and showed how he fitted perfectly into a square and an equilateral triangle according to the dictates of the Golden Mean. Vitrvius also outlined 3 principals that underpinned his branch of architecture. 1. firmitas – buildings must be built of strong and durable materials 2. utilitas – buildings must be functional and usable 3. venustas – buildings must be beautiful. This last one is complicated. Simply put, it must look beautiful but beyond boasting exquisite decoration it must conform to the mathematical laws of proportionality If all these principals are adhered to then the resultant building will through its proportional symmetry convey a sense of eurythmia: an intrinsic harmonous beauty. Roman Art & Architecture: A work in progress Key Elements of Roman Architecture Columns Due to early contact with Greek colonists in southeast Italy and Sicily the Romans absorbed Greek styles of columns into their architecture. There are three orders of Greek columns: 1. The Doric Order often plain in appearance, slightly fat and lacking a base 2. The Ionic Order elegant, narrow, tall and crowned by the distinctive capital decorated simply with ram-horn volutes 3. The Corinthian Order like Ionic columns but crowned by a seeming floral display that sometimes incorporate ram-horns but the acanthus leaves that appear to grow organically define Corinthian columns Column shafts can be either fluted (with ridges and grooves) or unfluted (plain) Illustration not in Wheeler In addition to the order a building took from the columns it featured in its façade it also had a style. The style of a building can be discovered simply by counting the number of columns of the façade in Greek. Four columns = tetrastyle, six columns = hexastyle, eight columns = octostyle, ten columns = decastyle … For more on this see the section on Temples. Roman Art & Architecture: A work in progress Arches The arch was known to the Egyptians and the Greeks but never used to its potential until Roman times. The Greeks favoured the post and pillar format of the temples for their public buildings but this limited them in terms of the available space they could leave in a building. They made fine use of triangular roofs however but again the structures suffered from great stresses and strains, which limited the Greeks to using very strong, hard and expensive marble. The arch could be constructed with anything from cheap brick to polished marble and allowed the Romans to play with space. Roman arches were constructed from unmortared (no cement) voussoirs (wedge shaped blocks) which were held in position by a central keystone. Thrust is the term given to the downward and outward force exerted by the combined weight of these blocks and the great weight that they often supported. In many buildings, supporting walls had to be reinforced by means of strong thick walls known as buttresses that stopped the arch from collapsing due to the thrust of its load. Illustration not in Wheeler When several concentric arches are combined they formed a tunnel known as a barrelvault. When two barrel-vaults intersected at right angles they formed a cross-vault and when an arch was constructed in three dimensions it formed a dome. Roman Art & Architecture: A work in progress Building materials Stone Tufa These illustrations are not in Wheeler Travertine Pentelic Marble Porphyry Alabaster Tufa is an igneous (volcanic) rock like pumice, which ranges in its strength and hardness. It is distinctive due its pock-marked appearance; caused by trapped air bubbles in the cooling lava. Travertine is a sedimentary limestone (sometimes mistakenly identified as marble) that comes from a large quarry in Tivoli near Rome. It is typically pock marked and porous and can be polished to a fine finish. The Colosseum’s exterior is constructed almost entirely from travertine. Its actual name in Latin was lapis tiburtinus - stone from Tibur (ancient Tivoli). It comes in a variety of colours ranging from light brown to mottled red. Pentelic marble is a fine white marble imported from the Athenian quarry in Greece. A similar Italian marble was quarried at Luna. Porphyry a highly prized redish purple granite was imported from Egypt at huge expense. Alabaster (sometimes known as gypsum) is a soft whitish chalk quarried in Tuscany, north of Rome. It was used for carving decorations. When heated in boiling water it acquires a translucent quality resembling true marble. Albaster is properly a natural mineral compound rather than an actual rock. Compounds Stucco Illustrations not in Wheeler Stucco is a durable cement-like plaster made simply from lime, sand, marble dust and water. It was used in varying consistencies (ratios of contents to water) as a dressing for exteriors and interiors alike. Roman Art & Architecture: A work in progress Concrete is a compound material made by mixing mortar (lime, sand and water) with an aggregate: usually gravel or sometimes broken pottery. It was originally discovered by the Egyptians but they failed to realise its potential. In the 1st century BC however the Romans became masters in the uses of concrete. Concrete suffers from thrust and often cracks along faults in walls. This is due to the fact that concrete is porous and so it swells and shrinks depending upon its water content. The Romans however discovered that when mixed with pozzolanic ash (a volcanic ash of varying colours found around Mt. Vesuvius near Naples) at a ratio of 2:1 with lime before being added to the mixture of sand, aggregate and water the resultant concrete was slow drying, water proof once dry and very hard wearing. Roman water channels and sewers were coated in this type of concrete and sections of the original aqueduct in Rome are still in use today. The Roman harbour at Cosa in Tuscany was built with Roman concrete and also remains in use today. Concrete was often faced with slabs of marble to make the walls look more appealing but the Romans were very fond of building walls with concrete because it was so strong, moldable and cheap. Roman Art & Architecture: A work in progress Roman Roads All roads lead to Rome. 3 Famous Roads of Rome Via Appia “the queen of the long roads (Statius)” and main road to the south. Length: 211km south from Rome to Capua – the original road. Built by Appius Claudius Caecus (censor) 312BC. It was the first long road built specifically for troops to march to and from Rome. It crossed the Pontine Marshes to the south which had up until that point formed a geographic obstacle (and a high risk of malaria) to the Romans in their skirmishes with the nearby Oscan tribes. 71BC 6000 defeated slaves of Spartacus’ slave revolt were crucified along the Via Appia between Rome and Capua. It was extended several times afterwards by a further 375km and finally by Trajan in the 1st century AD to Barium (modern Bari) and Brundisium (Brindisi); ports on the heel of Italy. Roman Art & Architecture: A work in progress Via Flamina – most important road to the north. Built by Gaius Flaminus (censor) 220BC. Length: 311km It begins just inside the northern gate of Rome in the Aurellian walls at Porta Flaminia (now Piazza del Popolo – the square of the poplars) and ends in the ancient city of Ariminum (Rimini) on the Adriatic. Under Vespasian in AD69 the tunnel through the mountain at Furlo was enlarged. It is still used today along the modern highway known as the SS 3 Flaminia. Via Sacra The oldest and consequently most sacred street of Rome. It begins on the Capitoline Hill, passed through the Forum Romanum and ended at the Colosseum. It passed some of the most sacred sites in Rome hence the name and formed part of the Via Triumphalis – a route rather than a road used by victorious consuls during Republican times and later by Emperors on their triumphal parades. All road distances were calculated from the same starting point: the so-called golden milestone that stood in the Roman Forum. It was said to be the heart of Rome. If all roads led to Rome, they led to the golden milestone. Bridges A bridge is a continuation of a road where no road can be built. Roman bridges are a testament to Roman stone masonry as much as they are to the use of the arch. Roman bridges were constructed with unmortared masonry (no cement). Dry rectangular stone blocks were put together in stretcher and header courses: one layer of blocks was laid lengthwise, whilst the next was laid perpendicular. The blocks were then dovetailed together (held by pressure caused by small wedge shaped blocks hammered between them) or else held together by means of metal pins. And in true Virtruvian style bridges often featured graded arches, the largest being at the centre and grading down in size symmetrically to the sides. Roman Art & Architecture: A work in progress The Milvian Bridge in Rome Wheeler, p.152, il.135 Built by Consul Marcus Aemillius Scaurus in 109BC to replace the original wooden bridge built by Consul Gaius Claudius Nero (not the famous Emperor Nero) in 206BC. Built primarily of unmortared tufa but faced with travertine Bridge is slightly hump-backed but the hump is located between the 3rd and 4th arches to meet the slightly higher bank on one side. Two barrel-vaults flank the 4th arch forming flood-passages to relieve the bridge when the Tiber is in flood. Similarly the imposts (feet of the piers) are wedge shaped on the up-river side. These act as breakwaters that direct the force of water through the arches and off of the piers. The viaduct on top is 8m wide and enclosed by two parapet walls on either side. 6 arches. The widest spanning almost 60ft/18.55m The bridge carried the Via Flaminia across the Tiber. It would have been used as a main thoroughfare for the movement of people and goods. Incidentally It was the scene of a famous battle (The Battle of the Milvian Bridge) during the civil war between Emperors Constantine I and Maxentius in AD312; a battle in which Constantine was victorious. Roman Art & Architecture: A work in progress The bridge across the Tagus valley at Alacantara in Spain Wheeler, p.153, il.136 Located at the city of Alacantara near the border between Spain and Portugal. Built of unmortared granite There is a dedication to Trajan on the triumphal arch at the centre IMPeratori. CAESARI DIVI NERVA Filio. NERVAE TRAIANO AVGVSTO GERMANICO DACICO PONTIFici. MAXimo. This is the official title of Trajan as Emperor. The inclusion of Dacico means that the inscription was carved after Trajan’s triumph on return from Dacia (AD102). Bridge built by AD106 The piers are buttressed to withstand the thrust of the arches and held together by means of metal clamps to withstand the pull of the river. The up-river sides are rounded so as to act as breakwaters, which direct the flow of water through the arches and stop the water from exerting full pressure on the piers themselves. The widest arches at the centre measure 94ft/28.8m The length of the bridge is almost 200m (194m). The viaduct is 8m wide At the highest point, the bridge is more than 50m above the river. 6 arches in total hold up the viaduct linking the two sides of the Tagus ravine. There is a little Roman temple on the city side, bearing a dedication to the bridge builder: Gaius Julius Lacer. Incidentally The bridge was damaged several times in the medieval period by the Moors, Spanish and the Portuguese. Less than masterful repairs were made using cement, which serves to prove the mastery of the Roman stone masons. Roman Art & Architecture: A work in progress Waterworks: Aqueducts & Cloaca Past influences and precedents The Greeks Polycrates of Samos (a Greek island) famously cut a water channel that stretched some 1,100ft long linking a water source with the city. It was in essence an aqueduct as it was covered. It was however crudely constructed, being simply hewn through the rock. Persians & Etruscans The Persians had used qanats to irrigate the arid landscape of Iran long before Rome was even founded. The Phoenicians acquired this technology and it quickly spread throughout the various Punic colonies scattered throughout the Mediterranean, including Etruria (Tuscany).The Romans therefore perfected an earlier Etruscan method of irrigation and drainage. A qanat – which is a Persian word – was a purpose built underground water channel that sloped very gradually downward from higher ground, from an aquifer - a subterranean water rich layer of permeable rock. This was tapped. Vertical shafts were then dropped at regular intervals along the channel from which water could be drawn. The channel would eventually come out into the open in the foothills where it would become a canal that would irrigate the surrounding landscape. Illustration not in Wheeler Roman Art & Architecture: A work in progress Aqueducts illustration not in Wheeler Aqueducts were purpose built Roman water channels in which the gentle flow of water was carried by the force of gravity. The ducts themselves (like the one pictured above) were lined with fine concrete mixed with pozzolanic ash. This formed a waterproof seal that prevented leaking. The duct was then covered with stone slabs to protect the water from animal and fecal contamination. The duct was then buried underground. What we refer to as an aqueduct today is usually only a tiny portion of the original aqueduct. Of all the aqueducts in Rome, only 10% are visible above ground. The aqueduct bridges, which we mistakenly call aqueducts, were brought into use to carry aqueducts across irregular terrain like valleys and ravines. The aqueduct bridges that survive are as much a testament to Roman surveying as they are to engineering and architecture. The line and levels of aqueducts had to be exact. Aqueducts do not tolerate many twists and turns. The flow of water has to be gentle and very slight, so the straighter and more gradual the gradient the less likely the water is to erode the channel from the inside. For example, the Pont du Gard outside Nimes in France drops only 34cm per kilometre and drops only 17m vertically in its entire length of 51km (30 miles). Vitruvius was the first to describe how water finds its own level and therefore aqueducts work by the power of gravity. He went on to describe in great mathematical detail the problems facing any aqueduct. The fragility of the watercourse was the main one. The flow of water had to be gentle to prevent erosion of the channel and blow outs and despite the precision of Roman engineering, aqueducts had to be constantly maintained so as to guard the purity of the water, which they carried. Incidentally In AD95 Emperor Nerva appointed Frontinus, one of his generals, to the position of curator aquarum charged with carrying out a full survey of all 11 aqueducts that served Rome. At the end of the first century he published “De Aquaeducto”, which counts as the first published survey of public works. Thanks in part to Vetruvius’ original calculations he was able to detect discrepancies between the in-take and out-fall volumes and to uncover illegal tapping of the aqueducts by individuals and local industries. Roman Art & Architecture: A work in progress Single Tiered Aqueduct of Hadrian in Carthage Wheeler, p.150, il.133 Built AD131 Original length 90km/55 miles from Zaghoun mountains to Carthage, modern Tunis. Built primarily of local sandstone and reinforced with brick Double Tiered Aqueduct of Segovia in Spain Wheeler, p.151, il.134 Wheeler says it was built c.AD10 but recent research suggests that it was probably later: between the late 1st and early 2nd centuries AD during the reigns of Emperors Vespasian or Nerva. Built of unmortared granite blocks 36 arches on each tier The upper arches are smaller but wider: 5.1m/16.1ft. The lower arches are taller but narrower: 4.5m/14.8ft Combined height including the water channel is 34m at the centre Roman Art & Architecture: A work in progress The total length of the aqueduct bridge is approximately 900m Simple moulded imposts break the monotony of the piers: 2 on each pier of the upper level and 4 on most piers of the lower level except towards the sides where it is the lower piers that grade away gradually. At the top the water channel is lined with concrete and which forms a U shaped duct 0.55 by 0.46 meters (1.8 by 1.5 feet) and was once covered with granite slabs. Incidentally It was partially destroyed by the Moors in the Middle Ages but carefully restored to its original glory by King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella in the 15th century. Three Tiered “Pont Du Gard” in Nimes, France Wheeler, p.150-51, il.132 Built c.AD14 Total length of aqueduct was 50km/31miles from Fontaines d’Eure near the modern town of Uzes to the Roman city of Nemausus (Nimes). Total length of aqueduct bridge at highest level: 275m across the small Gardon river Combined height of all the tiers was 49m/180ft above the river Lower tier: 6 arches, 142 m long, 6 m thick, 22 m high Middle tier: 11 arches, 242 m long, 4 m thick, 20 m high Upper tier: 35 arches, 275 m long, 3 m thick, 7 m high Water channel: 1.8m/(6ft) high, 1.2m/(4ft) wide and has a gradient of 0.4% The whole aqueduct delivered 6 million gallons of water daily to Nemausus Breakwaters and wide span of 6 lowest tiers eliminate water erosion from river Moulded imposts break the monotony: 2 on uppermost tier of piers & 3 on the middle. The aqueduct bridge doubles as a viaduct on the first level, though the modern road is actually a newer bridge built in the 18th century to safeguard the Roman aqueduct. Some of the granite blocks weigh as much as 6 tons bear the original Roman mason marks indicating their exact place and number right or left. Roman Art & Architecture: A work in progress Cloaca Maxima (Great Sewer) of Rome Wheeler, p.148, il.131 Built by the Etruscan kings prior to the foundation of the Republic by Tarquinius Priscius c.600BC. It was originally fed by three streams from the hills around the forum and was for the most part an open drain, though certainly some of the lower parts must have been tunneled below ground. The technology is basically a reverse qanat. Instead of drawing water from the main channel, waste was added through drains. In 33BC Marcus Agrippa an accomplished general and then an elected aedile (responsible for public works) as well as a close personal friend of Caesar Augustus carried out extensive and badly needed maintenance of the sewers. He perfected the Etruscan drains and turned them into a fully functional city sewage network. The barrel vaulted tunnels were probably added at this time. There were six other sewers in Rome that ran into the Cloaca Maxima just before it reached the outfall into the Tiber (pictured above) near the ancient bridge nicknamed the Ponte Rotto (broken bridge). Actually the outfall is to the left of the modern Ponte Palatino as one crosses the Tiber from the Forum Boarium to Trastevere. The Ponte Rotto is on the right. By the 1st century AD the 11 aqueducts that supplied Rome with fresh water ultimately ended in the Cloaca Maxima so the water pressure in the sewer was kept constant. This flushed out blockages. The sewer had its own goddess, Cloacina – an aspect of Venus. A shrine to Venus Cloacina was erected in the Forum Romanum directly over a drain to the sewer. Janus was also somehow connected to the sewer, as Constantine I erected an arch to Janus Quadrifrons (4 headed Janus) again over a drain to the Cloaca in the Forum Boarium (the cattle market). The specific meanings of these cults have been lost over time but the Romans must have felt that these deities were as important as their sewers; else they would not have built shrines to them. Roman Art & Architecture: A work in progress Triumphal Arches By way of introduction to Triumphal Arches Wheeler says, “From the exploitation of the arch in a functional capacity it was but a step for a society so demonstrative and wealthy as the Roman to elaborate it in monumental isolation.” (Wheeler, p.152). Triumphal arches are curious for this reason. From their earliest appearance in Roman civilisation they stood in monumental isolation showing no apparent regard to functionality or utilitarian concepts. This fact sets triumphal arches up against one of the founding 3 principals of the Virtruvian philosophy that seems to underpin Roman architecture. These arches perform no function other than to act as “ … a facet of the personality-cult which lies at the heart of the Imperial idea.” (Wheeler, p.153). The very first arches however appeared during the time of the Republic in the 2nd century BC. One of these early arches was placed on the spina in the Circus Maximus by one L. Stertinus on his triumphant return from Spain. Elsewhere in the colonies of the Empire they often replaced the gates of cities, which at least lent them some use but in several places they traversed the road leading into a city leaving the modern historian guessing as to their function other than perhaps to mark the limit of the pomerium – clear space around a city. Writing in the 1st century AD the historian Pliny the Elder called the triumphal arch a “new-fangled invention” which suggests that the craze was poorly understood even by the most learned of men. It seems Wheeler may be right when he says that, “… their ostentatious inutility has commended these costly ornaments, these towering advertisements, to the Herrenvolk (common folk) mind.” (Wheeler, p.153). Wheeler perhaps is right because these arches were indeed extremely popular. In Rome alone there were more than 50 built throughout the city. It seems they were placed as focal points in busy areas as “ … a decorative adjunct to some particularly frequented spot: celeberrimo loco …” (Wheeler, p.156) as an inscription from the Arch of Augustus in Pisa put it. In some cases access to them was hindered by steps, blocked and even prohibited by law. They were not bridges as they stood in isolation. They were not tombs. They supported nothing but an upper storey that carried nothing except artwork and dedications. They were in essence bill-boards glorifying whosoever built them. There were several different kinds of triumphal arch: Single and Triple arched arches and three-way and four-way arches. Roman Art & Architecture: A work in progress The Single Arch of Titus in Rome Single Arches like the Arch of Titus in Rome appear in greater concentration in the western half of the empire, i.e. Europe. Built c.AD81 Located on the Via Sacra, south-east of the Forum Romanum Built by Emperor Domitian and dedicated in memory of his older brother Emperor Titus and the sack of Jerusalem in AD70. Pentalic Marble imported from Greece The corners are articulated with engaged fluted Corinthian columns, though the capitals also sport ionic volutes. They count as the earliest example of the composite order. The entablature juts out over the column capitals The soffit (archway ceiling) is coffered and bears the image of the apotheosis (deified image) of Titus at the centre The barrel vault is decorated by panel reliefs. One depicting the Romans seizing the Temple spoils in Jerusalem including a sacred Jewish menorah. The other shows Titus attended by a procession of lictors (traditional attendants/bodyguards) indicating his importance. The attic storey was originally surmounted by a bronze quadriga (a chariot drawn by four horses) probably driven by a statue of Titus. A dedication to Titus is inscribed on a plaque over the arch on the attic section. It reads: SENATVS POPVLVSQVE·ROMANVS DIVO·TITO·DIVI·VESPASIANI·F. (Filio) VESPASIANO·AVGVSTO Which means The Senate and People of Rome (dedicate this) to the divine Titus Vespasianus Augustus, son of the divine Vespasian. It is not known whether the opposite side ever held an inscription but Pope Pius XVII placed one there in his own honour after he refurbished the arch in 1821. The new inscription was intentionally made on travertine marble to differentiate it from the original pentallic marble. This single triumphal arch provided Napoleon’s architects with the inspiration for his Arc du Triomphe in Paris Roman Art & Architecture: A work in progress Trajan’s Triple Arch in Timgad Wheeler, p.154, il.137 Later on and elsewhere in the empire the triple arch became more popular, probably because it guaranteed more space for decoration. An impoverished example is the Triple Arch of Trajan at Timgad, Algeria. It was built in the 2nd century AD and replaced the west gate of the colony, so it was slightly more functional than other arches. Unfortunately its state of preservation is poor. It seems to have been a modestly decorated arch. Built of local sandstone The axial archway is flanked by two piers, each with a smaller arch within. The piers are flanked by twin freestanding fluted Corinthian columns which appear to support broken round headed pediments in the attic storey. Rectangular niches appear over the smaller arches and below the broken pediments. Only one is still flanked by smaller ornamental Corinthian columns. The niches and small arches on the piers are separated by moulded imposts which carry across the breadth of each pier directly below the axial arch breaking the monotony. The entablature of the attic storey is simple. Although the earliest form of the trimphal arch to appear in Rome was the single form (like that of Titus), by the early days of Principate (early empire) the triple form had also emerged. The larger edifice granted a longer attic storey and therefore more space for decoration and dedications. Roman Art & Architecture: A work in progress The Triple Arch of Constantine I in Rome Wheeler, p.158, il.140 Built AD315 Commemorates Constantine’s victory against Mexentius at the Battle of the Milvian Bridge, AD312. Located between the Colloseum and the Palatine Hill. It intentionally spans the Via Triumphalis – the route taken by all emperors on a triumphal parade. It is worth mentioning that the architect included spolia – robbed and re-worked material from earlier monuments in its decorations. The main arch is built of travertine marble and the attic storey is built primarily of brick revetted with travertine marble, to reduce the weight the barrel vault supported. The re-use of earlier art work or spolia may be explained in 2 ways: propaganda or speed of construction, and probably a mix of both. Propaganda: the earlier artwork was taken from pre-existing monuments built by the good emperors of Rome: Trajan, Hadrain and Marcus Aurelius with whom Constantine wished to stand in the minds of his people. Speed of construction: the arch was commissioned and built hastily to commemorate Constantine’s victory over Emperor Maxentius during a civil war that broke the imperial tetrarchy – when Rome was ruled by four. He had to celebrate a triumph quickly. The arch took 3 years to build after the Battle of the Milvian Bridge. The spolia may therefore have been used for the purpose of expediency as new ark works would take too long. On the attic storey, flanking the inscriptions are pairs of relief sculpture taken from some earlier monument built by Marcus Aurelius comemorating his victories over the barbarians. The reliefs tell a sequential storey by episodes. They show the Emperor leaving the city, distributing money to the people, at war, interrogating a prisoner, accepting surrender by the defeated cheiftain, a triumphal parade with hosts of prisoners, the emperor addressing his troops and piously offering sacrifice to the gods. The emperor depicted is clearly Aurelius and has not been reworked to present Constantine. But Aurelius’ son Commodus has been Roman Art & Architecture: A work in progress eradicated following his damnatio memoriae – he was a wicked tyrant who was eventually assassinated and his memory was struck off the official historical record. This was an ancient practice that was first used by the Egyptians for Pharaohs they wished to forget like Akhenaten or Queen Hatsheput. The smaller sides of the attic as well the inner passages of the barrel vault feature friezes taken from Trajan’s Forum celebrating his victories in Dacia. The main façades on either side is divided into three by 4 fluted disengaged Corinthian columns made of yellow marble imported from Numidia (ancient Algeria). The spandrels of the main arches feature Victory goddesses presenting laurel wreaths. The spandrels of the minor arches feature river gods. These are original works. Pairs of round reliefs appear above each of the minor archways depciting scenes of hunting and sacrificing. They were originally Hadrianic but the faces of the emporer have been reworked to resemble Constantine. Two medallions appear on the smaller sides of the sun in his chariot rising on the eastern side and the moon in her chariot descending on the western side. This is a common pattern, the greatest example of which appears on Phidias’ eastern pediment of the Parthenon in Athens. The main pieces of original artwork commisioned by Constantine is a fireze that runs around the monument between the minor arches and the medallions. These depict sequential episodes of the civil war: The depatrure from Milan, the sige of Verona, the Battle of the Milvian Bridge and the Emperor entering Rome. There is no depiction of the triumph however, perhaps because Constantine did not want to appear triumphant over Rome itself. Minor inscription proclaim him also as Rome’s liberator. The main inscription reads: IMP · CAES · FL · CONSTANTINO · MAXIMO · P · F · AVGUSTO · S · P · Q · R · QVOD · INSTINCTV · DIVINITATIS · MENTIS · MAGNITVDINE · CVM · EXERCITV · SVO · TAM · DE · TYRANNO · QVAM · DE · OMNI · EIVS · FACTIONE · VNO · TEMPORE · IVSTIS · REM-PVBLICAM · VLTVS · EST · ARMIS · ARCVM · TRIVMPHIS · INSIGNEM · DICAVIT To the Emperor Caesar Flavius Constantinus, the greatest, pious, and blessed Augustus: because he, inspired by the divine, and by the greatness of his mind, has delivered the state from the tyrant and all of his followers at the same time, with his army and just force of arms, the Senate and People of Rome have dedicated this arch, decorated with triumphs. Instinctu divinitatis may allude to Constantine’s shifting religious beliefs. Constantine was the first Christian emperor. He didn’t make the traditional sacrifices to the Roman gods after his triumph in 315. After the celebrations he simply returned to his palace. This triple triumphal arch was the inspiration for the design of Napoleon’s “little” Arc du Triomphe at Place du Carrousel in Paris. The famous Arc du Triomphe at the other end of the Champs d’Elysee was inspired by the arch of Titus. Roman Art & Architecture: A work in progress If one were to seek a single emblem for the combined majesty and ostentation of a successful Rome, those monstrous toys the triumphal arches were difficult to deny (Wheeler, p.158). A reconstruction of one of “those monstrous toys” The Four-Way Arch of Septimius Severus at Lepcis Magna Wheeler, p.155, il.138 Of uncertain date but Wheeler is correct to estimate a middle date of c.AD200 because relief carvings depict Parthians as the defeated enemy who Septimius Severus fought early in his reign and Caracalla, his son and heir features a tall adolescent boy in the reliefs. By AD200 Caracalla would have been a teenager. The Arch was built and financed by the citizens celebrating the city’s most famous son: The Emperor who brought the stability to Rome in the year of the 5 Emperors: AD193. Septimius Severus was born in Lepcis Magna. It was located just outside the city at the north-east end of the cardo on an island mounted by steps. Traffic was circumvented around it. It is built of unmortared local limestone. The present day arch that stands is largely a reconstruction. Only the foundations and partial ruins of the piers were uncovered by excavation in the 1920’s. There is a remarkable disparity between the craftsmanship of the friezes. Some are clearly the work of master sculptors whilst others are common carvings. The limestone blocks of the central pier were also measured in Punic cubits, whereas those of the outside arches were in Roman feet, which again suggests there was a pause during construction. It is reasonable to assume that the city commissioned the work as soon Spetimius Severus took power in 193 but that the progress was slow and then finally the arch was finished quickly, perhaps in time for the Emperor’s visit AD202-03. Architecturally the quadrifrons form of the arch is a cross vault, i.e. 2 intersecting barrel vaults. Roman Art & Architecture: A work in progress This type of arch is rare but not unique but they do seem to be limited to Africa. There is another 4 way arch nearby at Oea (modern Tripoli) dedicated to Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus. Each of the four ornately decorated arches jut out from a more simple main cross vaulted block of piers that must have been built earlier. The arches are crowned by broken pediments supported by un-engaged fluted Corinthian columns, whilst the arches themselves appear to be supported by beautifully ornate Corinthian pilasters. The style of decoration is a fusion of orthodox imperial Roman monumentalism, with a Greek bohemian edge and there is also unsurprisingly a Punic quality – Lepcis Magna was a Punic colony. The two protective deities of the city who were originally Punic appear in the reliefs. Milkashtart – the male consort of Astarte who was likened to Hercules by the Romans and Shadrapa – a Phoenician healing god linked to Dionysus. Therefore the arch is a testament to the extraordinary flexibility of Roman religion with regard to its respect and tolerance for the foreign cultures. Nikes (Greek Victory daemons) also appear on the spandrels (the panels to either side of each arch). A tendril and rosette frieze runs around the monument. Organic motifs also pervade throughout the monument’s decorations. Vines and grapes particularly lend the arch a Dionysian flavour as does the eastern quality to the entire work. Each side of the attic storey is decorated by relief carvings of the Emperor’s victories against the Parthians. The Three-Way Arch at Palmyra Wheeler, p.63, il.43 Probably dates to second century AD Inscriptions point to Septimius Severus or his son Caracalla (AD193-217) It is actually two triple arches juxtaposed at an angle to create a wedge-shaped junction in the decumanus masking a change in direction in the street towards the Temple of Bel. Roman Art & Architecture: A work in progress