Plain_Language

advertisement

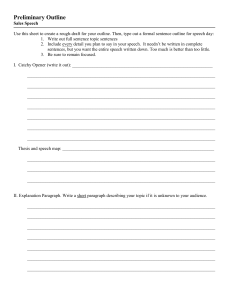

Administrative Policy Writing Spring 2011 Administrative Policy Writing Spring 2011 What is Plain Language? “Plain English is clear, straightforward expression, using only as many words as are necessary. It is language that avoids obscurity, inflated vocabulary and convoluted sentence construction. It is not baby talk, nor is it a simplified version of the English language. Writers of plain English let their audience concentrate on the message instead of being distracted by complicated language. They make sure that their audience understands the message easily.” (From plainlanguage.gov.) Administrative Policy Writing Spring 2011 Why is Plain Language Important? “Plain language” is the current movement in administrative policy writing at all levels of government. The plain-language movement arose as a reaction against bureaucratic style. Prose in the bureaucratic style is needlessly difficult to read, uses archaic words and phrases, and is generally inaccessible to the average citizen. The movement away from bureaucratic style emerged in the 1970s. Plain language advocates thought that the large volume of inaccessibly bureaucratic documents produced by the federal government was not appropriate in a democratic society. Government is supposed to serve the people. Administrative Policy Writing Spring 2011 Why Is Plain Language Important? Thus, plain-language reform is an effort is to make government communication readable and understandable. In the 70s and 90s, a series of executive orders mandated plain language in the federal government. The Plain Writing Act of 2010, signed by President Obama, requires heads of federal agencies to use plain language in documents produced by their agencies. So what is plain language? Administrative Policy Writing Spring 2011 Bureaucratic Style Before we discuss the elements of plain language, let’s look at what it isn’t to give you a sense of what the plain language movement is struggling against. The following is a “before and after” from plainlanguage.gov. The National Oceanic and Atmosphere Administration (NOAA) published a quick-reference document for boat operators “skippers” who are required to participate in training workshops put on by the NOAA. Administrative Policy Writing Spring 2011 Before and After Before: Huh??? Administrative Policy Writing Spring 2011 Before and After After: What are the differences? Administrative Policy Writing Spring 2011 What are the Elements of Plain Language? We are going to talk about the following elements of plain language over the next two weeks: Audience Paragraphs Sentences Word choice Our discussion today borrows a good deal from the Federal Plain Language Guidelines, a document published at plainlanguage.gov. You should download this document and review it to prepare the writing assignment for this unit. The link is on the course calendar. This week we are covering audience and paragraphs. Administrative Policy Writing Spring 2011 Audience Documents written in any context are usually directed toward one or more audiences, whether real or imagined. An audience may be one particular person or a group of people: Your boss A regulated industry The public at large Chemists State representatives A government agency Identifying your audience and writing for that audience and their expectations will enhance clarity and increase your ability to be persuasive. Decisions about word choice and presentation of material will depend upon your audience. Administrative Policy Writing Spring 2011 Audience Chapter 1 of your textbook discussed the concept of audience. The purpose of web-document rewrite was to exercise your ability to adapt word choice and sentences to make the document accessible to a defined audience. This concept applies to writing plain language. The idea is to write in a way that is clear and understandable to your audience. One example of such adaptation is the use of jargon. Jargon is “the vocabulary, peculiar to a particular trade, profession, or group.” (dictionary.com). When you are writing in a plain-language style, is it ok to use jargon? Administrative Policy Writing Spring 2011 Audience Answer: it depends on your audience. If you are writing to members of a group that has a unique jargon, they may expect to see it. If you are writing to the general public, you should seek to minimize it. In fact, you may need to understand and use an audience’s jargon in order to establish your own credibility with a particular profession or other group. Jargon can include Technical vocabulary: “The company has installed two electrostatic precipitators.” Terms of art: “consideration” has an everyday meaning and a completely different legal meaning. Acronyms: NPDES (National Pollution Discharge Elimination System) Consider the following manual published by the EPA. Administrative Policy Writing Spring 2011 Audience An electrostatic precipitator is a piece of pollution-control equipment used in various industries. It removes fine particles called particulate matter from an emission source (a smoke stack). Particulate matter is a form of air pollution. Who is the likely audience for a training manual on industrial pollution control equipment? Notice the document use of terms like “particulate matter,” “coal-fired utility boilers,” and “electrostatic precipitator” without any explanation. If the audience is already familiar with these terms, is the previous page written in plain language for that audience? Would an ordinary member of the public consider this document to be written in plain language? Administrative Policy Writing Spring 2011 Paragraphs The Guidelines list four elements of clear paragraphs: Have a topic sentence. Use transition words. Write short paragraphs. Cover only one topic in each paragraph. We will talk about each of these in turn. Administrative Policy Writing Spring 2011 Have a Topic Sentence The Guidelines provide: “If you flood readers with details first, they become impatient and may resist hearing your message. A good topic sentence draws the audience into your paragraph.” You have to be intentional about writing topic sentences because it is contrary to the way we think. often we think about a topic in a haphazard way. or we start with a conclusion, and then think of the reasons or necessary background information later. The topic sentence is not your conclusion. Rather, it is the general subject-matter to be developed in the paragraph. The ultimate conclusion of the paragraph may be near the end. Administrative Policy Writing Spring 2011 Have a Topic Sentence Also, the Guidelines point out that, especially in government documents, readers want to be able to skim the document and gather the essential information. Suspense, allusion, and metaphor are not valued in this genre of writing. Nobody is cozying up with a copy of government regulations or reports to read before bed. Clear topic sentences help your readers get the information they need quickly. Administrative Policy Writing Spring 2011 Topic Sentence Example Administrative Policy Writing Spring 2011 Topic Sentence Example Notice how the topic sentence orients us to the subject. We are talking about B&E Concrete. They manufacture construction materials. That is the preliminary information we need to understand this paragraph. The last sentence expresses a conclusion that is based on this topic and additional facts. Administrative Policy Writing Spring 2011 Topic Sentence Example If the conclusion were placed first, the paragraph would be harder to read. It would introduce too much information to process: the idea of this B&E company feedstock reports EPA enforcement Also leading with the conclusion is frustrating for the reader. The reader must take it as true and read the entire paragraph. The reader has to maintain that trust until the end of the paragraph. At that point, the reader might have to go back to the first sentence, read it again, and decide if your conclusion makes sense. Don’t require your reader to put in this extra effort. Use a topic sentence that logically leads to a conclusion so the reader can see how you got there on the first reading. Administrative Policy Writing Spring 2011 Use Transition Words Often topic sentences serve another purpose: they link one paragraph to another. Use transition words to show the reader you are linking ideas. The Guidelines discuss the following types: Pointing words: this, that, etc. Echo links: words or phrases that repeat previous ideas. Explicit connectives: therefore, accordingly, thus, etc. Let’s look at how they are used in topic sentences. Administrative Policy Writing Spring 2011 Use Transition Words Administrative Policy Writing Spring 2011 Use Transition Words I would add that the idea of transition words also applies within paragraphs. A well-constructed paragraph makes it easy to see the logical connection between ideas. Organize sentences so that they develop the idea of the previous sentence and ultimately reach your conclusion. Think of a paragraph as a chain of reasoning. Use transition words that refer back to a previous idea or show that you are constructing a chain: this, that, therefore, etc. Consider the example paragraph we have been using. Notice two things about: The logical development of ideas based the prior sentences. The use of transition words to signal this development. Administrative Policy Writing Spring 2011 Administrative Policy Writing Spring 2011 Write Short Paragraphs Short paragraphs are easier to understand. They ask readers to process the text is smaller, bite-sized chucks. Accordingly, short paragraphs are more likely to actually be read. This is especially true when writing in a public-policy context. Government regulations are extremely boring reading material. Thus, the subject matter of public-policy writing itself means you are starting with the distinct disadvantage in keeping an audience’s attention. Look at the following example. Do you want to read this? Administrative Policy Writing Spring 2011 Write Short Paragraphs Me neither! But the hard reality is that public-policy writers must deal with tedious and boring information. And often they have to communicate it to an audience that is distracted, has a short attention span, or doesn’t care. Use short paragraphs to make tedious writing less painful. Short paragraphs can mean as few as two sentences, or sometimes even one. (Yes, one.) Then use subject headings to break up the material into identifiable parts. Notice the short paragraphs and subject headings in the following guidance document on public drinking water systems. Administrative Policy Writing Spring 2011 Write Short Paragraphs What would the same document look like without the short paragraphs and subject headings? Administrative Policy Writing Spring 2011 Cover One Topic per Paragraph The Guidelines also suggest limiting the subject matter of paragraphs to one topic. For example: If you are discussing a procedure one must follow, make paragraphs based on each step. Don’t combine steps in one paragraph. It is easier for readers to skip a step. If you are discussing a subject that has many alternatives, treat each alternative as a separate paragraph. Administrative Policy Writing Spring 2011 Practice! Complete the plain-language exercise for this week. Link is on the course calendar. No writing project this week. Next week we will continue our discussion of plain language with sentences and word choice. Administrative Policy Writing Spring 2011 Plain Language Part II Sentences and Word Choice Administrative Policy Writing Spring 2011 Sentences We’re talking about writing in a “plain language” style. It is now the preferred style for government communication. The purpose is to make government communication clear and accessible. We’re using the Federal Plain Language Guidelines. The Guidelines include four elements for writing clear sentences I want to discuss: Write short sentences. Keep subject, verb, and object close together. Place the main idea before exceptions. Place words carefully. Administrative Policy Writing Spring 2011 Write Short Sentences This seems like pretty straight-forward advice. But it is often more difficult than it sounds. Public-policy writers have the challenge of conveying complicated information. Suppose a writer is tasked with explaining a series of requirements. However, this is made difficult by the fact that each requirement has different exceptions and other nuances. Consider the following sentence that tries to cover too much ground. Administrative Policy Writing Spring 2011 Write Short Sentences That is one sentence. Notice how hard it is to understand. What exactly is a public water supply system? How could this sentence be split into several? Administrative Policy Writing Spring 2011 Write Short Sentences That is much easier to read. Use of bullet points also helps. Administrative Policy Writing Spring 2011 Keep SVO Close The subject, verb, and direct object of a sentence usually convey the essential meaning. Other phrases and modifiers limit or qualify that essential meaning. When writers insert modifying phrases between subject and verb, the sentence becomes harder to read. Compare: The investigator observed an explosion. The investigator, after climbing to the roof-top of the refinery, observed at or near the time the suspect valve was opened an explosion. Consider the example given in the Guidelines: Administrative Policy Writing Spring 2011 Keep SVO Close If all the modifying information is important to the writer, how could the sentence be reworked? Administrative Policy Writing Spring 2011 Keep SVO Close How could you rework the example about observing an explosion? “The investigator, after climbing to the roof-top of the refinery, observed at or near the time the suspect valve was opened an explosion.” Assume all the information is essential to the writer’s purpose. Administrative Policy Writing Spring 2011 Avoid Confusing Constructions It is clearer to phrase an idea in positive terms rather than negative terms. Negative: You may not enter the pool unless the lifeguard is seated on the chair. Positive: You may enter the pool if the lifeguard is seated on the chair. Positive (emphasizing the exclusive condition): You may enter the pool only when the lifeguard is seated on the chair. Administrative Policy Writing Spring 2011 Place the Main Idea First Government regulations are often structured in a way that includes a general idea or requirement, and then a number of exceptions to that requirement. Sentences that put the exceptions first are difficult to read. Such sentences ask you to keep in your mind an exception to something which has not yet been revealed. Anytime you ask a reader to understand something you have not yet explained, you have lost clarity. “Except for carpeting, dishwashers, power tools, and yard equipment, everything at the hardware store is on sale.” About mid-way through the exceptions, you are probably wondering what this sentence is about. This is a very common fault in public policy writing. A textbook example from Texas solid waste regulations: Administrative Policy Writing Spring 2011 Administrative Policy Writing Spring 2011 Place Words Carefully The word “only” emphasizes the word or phrase that comes immediately after it. “The program is available only to those who make less than 150% of the federal poverty guidelines.” Versus “The program is only available to those who make less than 150% of the federal poverty guidelines.” If the sentence is emphasizing that the program is limited to those people, the first is preferable. Administrative Policy Writing Spring 2011 Place Words Carefully Put conditions after the main clause of a sentence. Why? Beginning of the sentence is position of emphasis. You usually want to emphasize the requirement you are talking about rather than the condition that triggers it. … But not always. Compare: “You must prepare a site investigation if H2O is found at the site in concentrations of greater than 2.0 ppm.” Versus “If H2O is found at the site in concentrations of greater than 2.0 ppm, you must prepare a site investigation.” Administrative Policy Writing Spring 2011 Words The Guidelines include elements for clear word choice. We will talk about four of them: Use active verbs Don’t turn verbs into nouns Omit unnecessary words Use words consistently Administrative Policy Writing Spring 2011 Active Verbs You were probably told in English class to avoid the passive voice. What is the passive versus active voice? Active voice: The subject of the sentence performs the action. Passive voice: The subject of the sentence is acted upon. In a passive sentence, the actor is either left unstated or is named in a “by” phrase. Examples: Active: The motorcyclist hit the pedestrian. Passive: The pedestrian was hit by the motorcyclist. Passive: The pedestrian was hit. The motorcyclist is the actor. In the first sentence, he is the subject. The subject of the second two sentences is the thing being acted upon, not the actor. The pedestrian is the one who was hit. Administrative Policy Writing Spring 2011 Active Verbs The passive voice can be problematic because it buries or obscures the actor. Thus, in order to write sentences with clear meaning, the active voice is usually better. Especially true in government writing that concerns obligations and responsibilities. If a sentence imposes an obligation on someone, you should always be clear about who that someone is. “The permit will be approved no later than sixty days from the submittal date.” Versus “The State will approve the permit no later than sixty days from the submittal date.” Administrative Policy Writing Spring 2011 Active Verbs The passive voice is appropriate in situations where you want to de-emphasize the actor or when the actor is unknown. “The store was robbed six times last year.” Robbed by whom? We might not know. Or the identity of the robbers might not matter in the context. Administrative Policy Writing Spring 2011 Don’t Turn Verbs into Nouns Sentences with strong main verbs are clear. Sentences are made weak by turning the verbs into nouns. When verbs are turned into nouns, they often require an additional phrase that makes the sentence unnecessarily wordy. “The FAA conducted an investigation of the site.” Versus “The FAA investigated the site.” Administrative Policy Writing Spring 2011 Don’t Turn Verbs into Nouns You can identify weak verbs by words like make, have, reach, or take. “The committee has reached a conclusion” “The committee has concluded.” Verbs that have been turned into nouns can often be identified with endings –ment, -tion, or -sion. “Please provide us an extension to file the letter.” “Please extend our deadline to file the letter.” Administrative Policy Writing Spring 2011 Omit Unnecessary Words If the audience clearly knows an abbreviation, it is ok to use without explanation. A letter addressed to the Federal Aviation Administration can use “FAA” to refer to the agency. (They know what it means.) Otherwise, use the standard convention for introducing an abbreviation or acronym. Spell out the term the first time it is used. Then put the abbreviation in parenthesis . Afterwards, use the abbreviation. Example: “The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) finds that you are no longer registered as a Type 3 pilot. Pursuant to FAA’s rules, pilots must maintain a registration.” Administrative Policy Writing Spring 2011 Omit Unnecessary Words One feature of bureaucratic style is the information dump. The writer fills sentences with as much information as possible without regard to whether it is relevant. It is a defensive writing tactic: If you include every possible detail, reservation, or qualification, no one can ever fault you for not including it. But such writing becomes tedious and your message can be lost in the weeds of details. It is also a lazy way to write. The writer doesn’t want to think about which details or qualifications are really necessary. So just include them all. Administrative Policy Writing Spring 2011 Omit Unnecessary Words Sometimes it is necessary to include qualifications and supporting details like we saw in the above examples. You have to be judicious about it. Consider whether details are relevant to your audience. “The Board has finished reviewing your application as required by Rule 21 and the 2006 amendments to Rule 21.” If the recipient of this communication is someone who wants a permit, is it really relevant which rule requires the Board to review the permit? Maybe. But probably not. It all depends on the context. The lesson here is to consider whether such detail is really necessary. Administrative Policy Writing Spring 2011 Use Words Consistently If your writing refers to some object or entity, make sure you refer to it consistently. Suppose an entity has applied to renew several permits to conduct offshore drilling. Correspondence concerning this application may refer to multiple permits: the old ones and the renewed permits the entity is seeking. In such case, using the term “permit” may become ambiguous. Which permit? The old one or the new one? This is often where the use of defined terms comes in handy. Consider the following example: Administrative Policy Writing Spring 2011 Use Words Consistently Notice how the defined terms “2001 Permit” and “2002 Permit” help avoid confusion. Administrative Policy Writing Spring 2011 Practice! Complete the plain language exercise for this week. Then complete the letter revision project. Please note, the project incorporates several units: Professional Style Business Letter Formatting Plain Language