slides - Indiana University

advertisement

Linguistic Stress in Language

and Speech

Kenneth de Jong

Indiana University

Chapter N+1.

Suprasegmentals

• The last chapter in phonetics descriptions

• Consists of Tone, Stress, Quantity, may-be

juncture

• Or … fundamental frequency, loudness,

duration, may-be syllable stuff

• What do these have in common?

Chapter N+1.

Suprasegmentals

• Scary

• When doing basic transcriptions, we can sorta skip them -- e.g.

no tonal minimal pairs.

• … in English … (most languages have tone contrasts, most

languages have quantity contrasts)

• Tend not to fit well with a segmental model of phonetic structure.

• Vary with spoken context. Intonation is a property of the sentence;

duration varies overall by tempo; …

• Tend not to be as well understood (linguistically) as things like

‘aspiration’, ‘point of articulation’, & ‘vowel quality’

Stress

• What is it?

• Why is it?

• What does it tell us?

What stress is:

phonetic observations

• OK, we do need it in transcriptions:

‘deepened’ vs. ‘depend’

• D.B. Fry (1955, 1958, 1965): perception

–

–

–

–

F0 pattern (some complicated stuff about pitch)

Duration (longer)

Intensity (more intense)

Other stuff (vowel quality more extreme)

• Stress vs. Accent: making sense of context

– Accent: F0 pattern varies qualitatively by context,

e.g. statement vs. question

– Other stuff more attached to the word itself

What stress is:

Phonological observations

• Many languages have something similar

to English stress

– Cross-language studies, such as de Jong

& Zawaydeh (1998): Arabic is surprisingly

like English

• Various patterns appear in a number of

languages

– Keeping track of them all creates things

like metrical phonology

What stress is:

Metrical observations

• Reduced Contrast: Unstressed items can have fewer contrasts.

• Domain: Stress is expressed over a syllable.

• Alternation: Stressed and unstressed material tends to be collated.

• Spacing: Stresses tend to be distributed evenly.

• Accent Location: Stressed items often are the site for accents.

• Culminativity: Stresses may bear a one-to-one relationship with

a higher-level unit, such as a phrase.

• Weight Sensitivity: Stresses tend to fall on heavy syllables;

heavy syllables are ones with long vowels and sometimes

consonantal codas.

• Boundedness: Stress location is often fixed in relation to a

location within a word.

• Boundedness Variation: Stress locations may either be

determined by position in morpheme or by weight sensitivity.

What stress is:

Characterizing the ‘other stuff’

• Loudness vs. Clarity

• Loud people

– Brits: Sweet (1892), Jones (1960): pulmonic force ->

heard as loudness

– Americanists: Bloomfield (1933), Trager & Smith (1951)

– More sophisticated: Lehiste (1970), Beckman (1986)

• Clear people

– Brits: Walker (1781); Jones (1960): prominence =

distinctness

– Swedish research: Ohman (1967), Engstrand (1988)

– American speech: Kent & Netsell (1971); Harris, 1978)

What stress is:

Characterizing the ‘other stuff’

• Loudness vs. Clarity

– Speech production work

• Similarities

–

–

–

–

Open up vowels

Close down consonants for contrast

Make it longer

Loudness is a way of being clear

• Differences

– Care with respect to targeting

– Being clear is harder than being loud

What stress is:

Characterizing the ‘other stuff’

• de Jong (1995)

– Compare production of words with /o/ in context of coronal

consonants

– Use X-ray microbeam facility to see what’s going on inside

– Found vowels with further tongue body retraction

– Degree of retraction was not predicted by duration increases, so it

can’t be due to undershoot mechanisms

• de Jong et al (1993)

– Consonant coarticulation

• de Jong (1998)

– Looked at articulation of post-vocalic /t/ & /d/ with stress variation

– Find variation due to something like ‘degree of effort’

Illustrative Results

Tongue tip

movement patterns

for phrase:

‘Put the t__ …’.

Solid = unstressed

‘Put’,

Dashed = stressed

‘Put’

QuickTime™ and a

TIFF (LZW) decompressor

are needed to see this picture.

What stress is:

Hyperarticulation

• “Clarity”, sweet clarity

• Connected to ‘Hyperarticulation’ (Lindblom, 1990)

– Speech production happens in a sea of variability

– Some of this is due to ‘mode of production’

– Hypoarticulation = maximize production system

considerations

– Hyperarticulation = maximize likelihood the other guy will

understand you

• Hyparticulation local to the syllable (de Jong, 1995)

• More attention in production (de Jong, 1998)

What stress is:

Testing Hyperarticulation

• Lindblom: hyperarticulation = premium on getting

information in signal

• Hyperarticulation happens in corrective focus:

– “I said ‘bed’, not ‘chair’.”

• IF corrective focus => hyperarticulation & stress =>

hyperarticulation,

• THEN stress & corrective focus should have same

effect as corrective focus.

• de Jong & Zawaydeh (2000) & de Jong (2004) test

this with vowel duration and quality effects

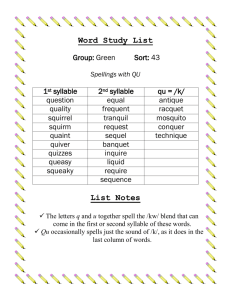

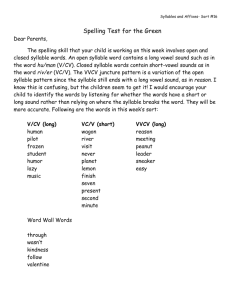

de Jong (2004): results for

voicing X vowel duration

Voiced

Voiceless

250

Vowel Duration (ms)

• Words like

‘flowerbed

• ‘bed’ longer

than ‘bet’

• Focus makes

difference

bigger

200

150

100

unfocused

focused

de Jong (2004): results for

voicing X vowel duration

{

{

Voiced

unfocused

focused

Primary

Secondary

Vowel Duration (ms)

• Add words like

‘bed’ - primary

stress

• ‘bed’ longer than

‘flowerbed’

• Stress & focus

have similar

effect

• Stress + focus

get even larger

effect

Voiced

Voiceless

Voiceless

300

250

200

150

100

de Jong (2004): results for

voicing X vowel duration

300

250

200

unstressed

Vowel Duration (ms)

• Add words like

‘rabid’ and ‘rabbit’

• Much shorter

• No voicing

difference

• Get a tiny effect

with focus

150

100

unfocused

focused

Results, de Jong (2004)

• To Summarize

– Both stress and focus increase duration

– Both stress and focus increase duration

contrast - specified differences get bigger

– Stress and focus interact so that contrasts

get much larger in focused & stress

material

– Side note on stress shift

What stress is:

General Attentional Model

• Other work on auditory attention in time (Jones, Kidd)

• Various properties

– Attentional selectivity: some parts of a stimulus are more

readily acted upon than others

– Attentional capture: parts which change in salient ways

tend to garner selective advantages

– Attentional integration: aspects which work together to

define an event get attended to as a unit

– Temporal expectancy: events forming regular temporal

patterns will focus attention on particular up-coming times

What stress is:

General Attentional Model

• Stress = some syllables are attentionally selected

• The attentional selectivity arises from attentional capture by

acoustic events with sudden changes

• And may exhibit attentional integration where bits of speech

which cohere and are regular form units

• Attention modulation can be governed by temporal

expectancy, wherein high attention areas can come at regular

intervals

• Attention modulation characterizes both hearer and speaker

– Speakers put important stuff in high-attention areas

– Hearers look for high-attention areas

– The match between speaker and hearer is A Good Thing

What stress is:

Phonological properties

• Reduced contrast: unstressed = low

attention area = a bad place for information

• Domain: syllable onsets = places of sudden

change => attentional capture; syllables tend

to be unitary acoustic objects => attentional

integration

• Alternation: since attention is relative,

attending to one event detracts attention from

neighboring events

What stress is:

Phonological properties

• Spacing: temporal patterning, especially regular

spacing in time, tends to make high attention areas

occur at regular intervals

• Accent location: accents help direct attention to

syllables which are hyperarticulated by the speaker

• Culminativity: if stresses are attentional objects,

having one stress per meaningful unit would make a

mechanism which allows speakers to present speech

a series of meaningful tasks

…. Good so far …

What stress is:

Phonological properties

• Weight Sensitivity: so … why DO syllables with a

final consonant tend to get stressed?

• Boundedness: and why do stresses come in

particular places in the word?

• Boundedness variation: oh yeah? if there are good

places in the word for stress, why are different

languages so different with respect to WHERE?

• Actually: if stress is so functional, Mr. Stress Man,

why DO languages stress different syllables?

• Better take a good look at language differences …

Korean Case Study:

Korean Stress Rule

• Korean stress rules

– Polianov (1936): if at end of utterance, stress the first

syllable, otherwise stress the last one

– Huh (1985) & Lee (1992): stress the first syllable always

– Lee (1974, 1985, 1989): ‘Weight sensitive’ -> stress a long

vowel or an initial syllable with a coda, otherwise stress the

second syllable

– Yu (1989): ‘Weight sensitive’ -> stress the first heavy syllable

you come to, otherwise stress the last one

– Lee (1990), Kim (1998): ‘Weight sensitive’ -> stress a heavy

first syllable, otherwise stress the second syllable

– Zong (1965), Cho (1967): ‘Unbounded’ -> it’s unpredictable

so you just memorize it.

Korean Case Study:

Lim (2000)

• Lim’s Expectations

Vowel Duration (ms)

200

175

150

125

100

75

Heavy

Light

Syllable 1

Syllable 2

Korean Case Study:

Lim (2000)

• Lim’s Expectations

– Stress heavy first

syllable

Vowel Duration (ms)

200

175

150

125

100

75

Heavy

Light

Syllable 1

Syllable 2

Korean Case Study:

Lim (2000)

• Lim’s Expectations

– Stress heavy first

syllable

– Stress light second

syllable

Vowel Duration (ms)

200

175

150

125

100

75

Heavy

Light

Syllable 1

Syllable 2

Korean Case Study:

Lim (2000)

• Lim’s Results

– No systematic

differences by

position

– No effect of weight

on position

Vowel Duration (ms)

200

175

150

125

100

75

Heavy

Light

Syllable 1

Syllable 2

Korean Case Study:

Lim (2000)

• Production Results

– No systematic differences in vowel durations, except that

vowels at the end are longer

– Syllable weight makes no difference

• Compares with Balinese production studies (Barber,

1977; Herman, 1998)

– Barber is a very reliable and experienced field worker who

relied on impressionistic transcriptions

– Herman ran acoustic measurement studies

– No systematic differences in vowel durations, except that

vowels at the end are longer

– Syllable weight makes no difference

Balinese Case Study:

Herman (1998)

• Barber (1977), first:

"There is no strong word-stress in Balinese in ordinary

speech, there is only a slight variation in loudness and

energy between the syllables of a sentence.”

• Barber (1977), then (same page later

on):

"In words of more than two syllables (not counting

suffixes), the penultimate syllable is stressed unless

the vowel is e."

Balinese Case Study:

Herman (1998)

• Herman (1998), her comment:

"It is theoretically impossible to prove that some entity

does not exist. Therefore, it is impossible to prove

that word-level accentuation does not exist in

Balinese. However, if word-level accentuation in

some form did exist, one might expect to find

certain indications of it."

Korean Case Study:

Lim (2000)

• Production Results

– No systematic differences in vowel durations,

• Summary

– KOREAN DOESN’T HAVE STRESS

– Korean Intonation Tutorial

Korean Case Study:

Lim (2000)

• Point: Though a stress system might be

functional, languages work perfectly well

without them.

• One more question: so what do we hear as

stress when listening to non-stress

languages?

Korean Case Study:

Lim (2000)

• Perception Results - ask them to locate stress

– Korean listeners tend to say stress occurs in the vicinity of a pitch

peak

– Pitch rises and falls in Korean are used to mark the edges of words

• Perception Results - suggests weight sensitivity

– The presence of consonants determines where, exactly, pitch

peaks show up

– If stresses ‘grow out of’ locations for pitch peaks, then consonants

can indirectly determine where stresses get located

– This can explain weight sensitivity

– This explanation doesn’t directly use attentional selectivity to

consonants.

Why is stress?

• The functional nature of attention modulation.

It has to do with the dynamics of speaker’s

production systems and/or the dynamics of

hearer’s perception systems and their

linkage.

• The not particularly functional nature of

language history. It has to do with the (much

slower) dynamics of language groups.

What does it tell us:

• The functional nature of stress

– Plasticity in production: people are more skilled

then they are given credit for.

– Acquisition patterns: not all segmental material is

created equal.

– Fluency complexity: speech takes place in a sea

of variability.

• The not particularly functional nature of

language history.

– Cross language differences and bio-physical

explanations

– Second language acquisition

de Jong (2004): results

Primary Stressed

Secondary Stressed

Uns tressed

{

{

{

Voiced

/œ/

Voiceless

/E/

Voiced

/œ/

Voiceless

/E/

Voiced

Voiceless

Vowel Duration (ms)

300

250

200

150

100

unfocused

focused

unfocused

focused