The Origin of Agriculture

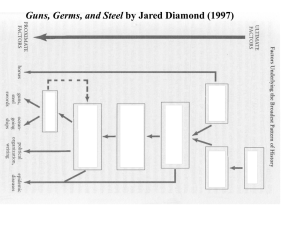

advertisement

The Origin of Agriculture “Cultural man has been on earth for some 2,000,000 years; for over 99% of this period he has lived as a hunter-gatherer. Only in the last 10,000 years has man begun to domesticate plants and animals … Homo sapiens assumed an essentially modern form at least 50,000 years before he managed to do anything about improving his means of production … To date, the hunting way of life has been the most successful and persistent man has ever achieved” (Lee and Devore 1968:3) Begin with the origins of Homo sapiens. Most anthropology texts begin the line from apes to modern humans about 5 MYBP with Homo habilis, or a more generalized form, called Homo africanus. There are almost as many schemes to get from the earliest Homo to us as there are qualified anthropologists. What they all have in common is an intermediate, Homo erectus. They differ in having varying numbers of “side branches” of Australopithecus spp. The modern species, Homo sapiens, seems to have evolved by about 500,000 years ago. It co-existed with H. neanderthalensis from about 300,000 to 30,000 YBP Australopithecus reconstruction Homo erectus A comparison of the skulls of Homo neandrithalis and Cro-magnon man (Homo sapiens) A comparison of neanderthal skeletal anatomy with that of modern Homo sapiens. The modern subspecies Homo sapiens sapiens was on the scene about 170 KYBP. They were hunter-gatherers. The ‘floors’ of campsites at Olduvai Gorge show that humans ate a varied diet including: fish, small rodents, fruits, roots and vegetables. The evidence that shows what this diet includes: charred or preserved remains of those foods, plant fibers, coprolites (fossilized poop), seeds and pollen of consumed plants, and microscopic evidence of crystals characteristic of particular plants (phytoliths). From your text: Plant remains clearly related to 25 different wild plant species at Wadi Kubbaniya in the Nile River Valley have been dated to ~17,000-18,000 YBP. Among those species are: wild nut grass (a sedge) tubers – high in carbohydrates and fiber, low in protein, but the protein is high in an essential amino acid, lysine acacia seeds – likely high in protein and lipids, as well as carbohydrates cattail rhizomes – rich in carbohydrates and fiber palm fruits - carbohydrates The tools needed to process those hunted and gathered foods include grinding stones, digging tools (to gather tubers), sickles to cut plants. The wear on hominid teeth indicates that a fair amount of grinding occurred on eating. There are still a few basically hunter-gatherer societies: • !Kung San – savannahs surrounding the Kalihari desert, southern Africa (Angola, Namibia, Botswana, Lesotho) • Inuit – arctic Canada, Greenland, northern Russia, Alaska – essentially • Ainu – forced to move northward onto Hokkaido, the north island of Japan by proto-Japanese cultures • Australian Aborigines • Bihors – northern India Modern culture has impinged on all of these groups, probably least so on the !Kung San. Study of the !Kung San diet during the 1960s found they utilized >100 plant species (about 2/3 of their diet) and 50 animal species. The diet includes: mongongo nut, other fruits, berries, melons, and roots; lizards, snakes, tortoises’ and birds’ eggs, insects and caterpillars, and some small mammals trapped by the women of the ‘tribe’. Meat from larger animals is only infrequently available, and celebrated when returned to villages. Men are only allowed to marry after they have made their first large animal kill. !Kung San hunters !Kung San musical instrument Shepherd tree (Boscia albitrunca) fruits and berries consumed, roots used to make a coffee substitute A gemsbok Tsamma melon (Citrulus lanatus) – watermelon-like, except that it remains firm and fresh for as long as 2 years. A springbok Caloric intake: 2,355 kilocalories/person/day 96 grams protein Full daily requirement of vitamins and minerals All this foraging only took 2.5 days/wk Probably a healthier, and certainly a more efficient diet than ours. Inuit family in an igloo Traditional hunting by kayak A modern Inuit community, Kimmirut (Lake Harbour) Ringed seal (Phoca hispida) being butchered on a beach Blubber stew Beluga whale being butchered A few plants are consumed, e.g. fireweed, various berries, Labrador tea, mountain sorrel. Most are high in vitamin content. Agriculture, meaning the culturing of plants and/or animals, began between 10,000 and 14,000 years ago, and arose without contact between cultures, at very similar times in many places around the world. What was first cultured differed among the key early sites? Here is a global map of those early sites of agriculture: Was the “origin” a revolution, or an evolution that involved beginning to culture well-known wild plants? Almost certainly the latter. What was cultured represented a selection of plants key to diets in the far-flung places where hunter-gatherer societies shifted from nomadic movement to localized settlement. In the fertile crescent (Iran, Iraq, Turkey, Syria, Lebanon, Israel) remains indicating the beginnings of agriculture date from 9,000 – 14,000 years ago. 1. Animals (dogs, goats, and sheep) were probably domesticated well before plants 2. Barley was probably the first plant domesticated there 3. Followed by einkorn wheat, emmer wheat, pea, lentil and vetch Einkorn wheat and its distribution in the wild Emmer wheat There were a number of sites where plants were domesticated in early agriculture in the Far East. The earliest site is along the Yangtze R. in China. Agriculture spread both north and south along the river. 1. Rice was domesticated ~11,500 years ago along the Yangtze. 2. Later (~8000 years ago) along the Yellow R. foxtail millet and, to lesser extents, broomtail millet, rapeseed (predecessor of canola) and hemp 3. Slightly later (but completely independently) plants were domesticated ~7,000 years ago in New Guinea highlands. Main crop species were taro and banana. 4. Animals domesticated in the Far East included chickens, pigs, dogs and cattle. In the New World, in Mexican highlands and Peru, a large number of plants and a few animals were domesticated, beginning about 8 – 10,000 YBP. 1. The earliest dated domestication is squash from a cave in southern Mexico. There are also phytoliths that indicate squash had been domesticated in Ecuador between 9 – 10,000 years ago. 2. By around 5,500 years ago there are numerous evidences of agriculture. Domesticated plants include: corn, chili peppers, amaranth, avocado, gourds, beans, various white (and coloured) potatoes, and sweet potatoes. Later peanuts, guava, and tomatoes were added. 3. Domesticated animals were dogs, llamas, alpacas, guinea pigs, and later muscovy ducks and turkeys. Amaranth (Amaranthus retroflexus) seeds are ground into flour. It was the main grain crop into the time of early European settlement. Purple Peruvian potato, a progenitor of the modern types of potatoes. In eastern North America (U.S. and Canada) agriculture began independently about 4,000 years ago. The major crop species were sunflower, marsh elder, wild gourd, and Chenopodium album, common name lamb’s quarters. Lamb’s quarters leaves are cooked as a pot herb, and taste a lot like spinach, with similar food value. Marsh elder (Iva spp.) Admission of failure: I’ve been unable to learn how marsh elder was used. Corn – there is a long history. The original domesticated corn was a perennial grass with very small cobs. The originally domesticated wild corn was not the modern agricultural species, Zea mays, but a perennial species still found in some sites in the highlands of central Mexico, Zea mexicana, common name teosinte. grains the plant Through artificial selection and saving grains from better and better Zea plants (probably mutants that appeared), we got from teosinte to modern corn: What are the characteristics that we might want in our domesticated plants? How do those characteristics relate to what can be expected from natural selection? 1. One of the first characters artificially selected (and opposite from desirable characters from natural selection) is how readily seeds are released and scattered from a plant. Natural selection points towards shattering fruit heads. Seeds or fruits are readily broken free by weak force (a breeze, and animal brushing by). To harvest seeds we want agricultural plants to be nonshattering. A single recessive gene makes Arabidopsis non-shattering. The gene in this species (AGL 15) is called shatterproof, and regulates the expression of other genes. A plant scientist at UCSD (Marty Yanofsky) has applied this genetic knowledge to canola growth. On the left, an Arabidopsis thaliana plant, and on the right the seed head of a shatterproof arabidopsis. 2. Plants are naturally selected to maximize fitness. In many cases that results in the production of smaller fruits, tubers or seeds, but larger numbers. In small-seeded plants like cereal grains the reverse may occur, with larger seeds having greater survivorship. We generally want more and larger. In barley, two-rowed barley is the wild character, while domesticated barley is sixrowed. The presence of sixrowed barley is considered an indication of agricultural domestication. The story of strawberries shows the results of sheer luck in artificial selection. Wild strawberries are tiny – the size of your little fingernail. There are a number of genetically distinct wild strawberries. There are two in Europe – a smaller English one and a somewhat larger one from Alpine meadows. In North America there is a wild scarlet strawberry and in South America a large-fruited, pale yellow strawberry described as tasting like pineapple. The two New World strawberries were exported back to France and, grown in common gardens, crossed by chance. Result: large size, almost scarlet colour, and lots of flavor. 3. We select for cooking and/or mechanical properties that clearly have nothing to do with natural selection. Two examples: • Nearly all commercial french fries are cut from ‘Russet Burbank’ cultivar • Selection for fruit shape optimizing shipping qualities is ongoing in tomatoes and watermelon 4. Winter dormancy is naturally selected. The mechanism is frequently hormonal. Abscisic acid accumulates in the seed coat of maturing seeds. It prevents embryo germination even when hydrated. It is broken down by an extended period of cool, wet conditions (spring). Selection for early or rapid germination (probably) selects for lower levels of sequestered abscisic acid in seed coats. This has been achieved in rapeseed. Its seed oil is used in cooking and for ‘biodiesel’ fuel. Sometimes the artificial selection introduces problems that were not, but (probably) should have been expected: 1. Selection for reduction in anti-herbivore chemicals, e.g. mustard oils, in a number of agricultural Brassicacea (canola,…) make them more vulnerable to pest insect attack. 2. Large scale monocultures produce large sources of cueing chemicals that attract insect herbivores, e.g. glucosinolates in crucifers (cabbage) attract diamondback moths. In us the glucosinolates (toxins) can cause liver and kidney lesions and thyroid enlargement. 3. Chemical content we want (higher sugar content in strawberries (Fragaria vesca) attracts egg-laying insect pests like aphids. We know where some of our agricultural plants were first domesticated, but where do modern agricultural species come from originally? A Russian geneticist, Nikolai Vavilov, gathered much of the early, key evidence from 1916-1936. His research was ended when he was sent to the Gulags. He was a Mendelian geneticist, but the Stalinist leader of agricultural genetics was Trofim Lysenko, who believed (mistakenly) in Lamarkian genetics. Vavilov died in the gulags in 1943. Vavilov proposed eight centers of origin, shown on the map of figure 11.6.