Chapter 5

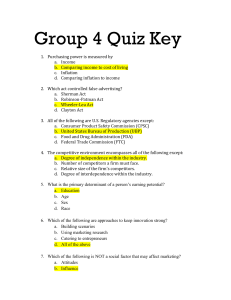

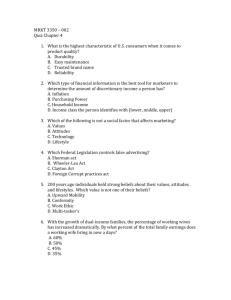

advertisement

Chapter 5

Inflation and Disinflation

© Pierre-Richard Agénor

The World Bank

1

Sources of Inflation

Nominal Anchors in Disinflation Money vs. the

Exchange Rate

Disinflation Programs: The Role of Credibility

Two Recent Stabilization Experiments

2

Sources of Inflation

Hyperinflation and chronic Inflation

Fiscal Deficits, Seigniorage, and Inflation

Other sources of Chronic Inflation

Wage Inertia

Exchange Rates and the Terms of Trade

The Frequency of Price Adjustment

Food Prices

Time Inconsistency and the Inflationary Bias

3

Hyperinflation and Chronic Inflation

Cagan's criterion: Hyperinflation is defined as an

inflation rate of at least 50% per month, or 12,975%

per annum.

Three main features of hyperinflation (Végh,

1992):

It typically has its origin in large fiscal imbalances.

Nominal inertia tends to disappear.

It brings about a chaotic social and economic

environment.

4

Example of hyperinflation: Zaire.

A deep and worsening political crisis led to a drastic

increase in government expenditure.

At the peak of the hyperinflation process, in

December 1993, inflation rose to almost 240% a

month.

During the whole period, domestic prices were

increasingly set in foreign currency.

Figure 5.1: during the whole episode, the monthly

rate of depreciation of the parallel exchange rate

remained closely correlated with the inflation rate.

5

F

i

g

u

r

e

5

.

1

a

Z

a

i

r

e

:

M

o

n

e

y

G

r

o

w

t

h

a

n

d

I

n

f

l

a

t

i

o

n

,

1

9

9

0

9

6

2 5 0

1

/

In

fl a

ti o

n

a

n

d

I

n

f

l

a

t

i

o

n

2 0 0

1 5 0

1 0 0

C

u

r

r

e

n

c

y

o

u

t

s

i

d

e

b

a

n

k

s

5 0

0

-5 0

1 9

1

9

9

0

1

9

9

1

1

9

9

2

1

9

9

3

1

9

9

4

1

9

9

5

9

S

o

u

r

c

e

:

B

e

a

u

g

r

a

n

d

(

1

9

9

7

)

.

1

/

M

o

n

t

h

l

y

r

a

t

e

o

f

c

h

a

n

g

e

o

f

t

h

e

s

t

o

c

k

o

f

c

u

r

r

e

n

c

y

o

u

t

s

i

d

e

b

a

n

k

s

.

6

F

i

g

u

r

e

5

.

1

b

Z

a

i

r

e

:

I

n

f

l

a

t

i

o

n

a

n

d

E

x

c

h

a

n

g

e

R

a

t

e

D

e

p

r

e

c

i

a

t

i

o

n

,

1

9

9

0

9

6

500

I

2

/

n

fl a

ti o

n

a

n

400

Z

a

ï

r

e

s

p

e

r

U

.

S

.

d

o

l

l

a

r

(

p

a

r

a

l

l

e

l

m

a

r

k

e

t

)

300

200

I

n

f

l

a

t

i

o

n

100

0

-1 0 0

19

1

9

9

0

1

9

9

1

1

9

9

2

1

9

9

3

1

9

9

4

1

9

9

5

9

S

o

u

r

c

e

:

B

e

a

u

g

r

a

n

d

(

1

9

9

7

)

.

2

/

P

a

r

a

l

l

e

l

e

x

c

h

a

n

g

e

r

a

t

e

i

n

t

e

r

m

s

o

f

o

l

d

z

a

ï

r

e

s

.

T

h

e

n

e

w

z

a

ï

r

e

w

a

s

i

n

t

r

o

d

u

c

e

d

i

n

O

c

t

o

b

e

r

1

9

9

3

a

t

a

p

a

r

i

t

y

o

f

N

Z

=

Z

3

,

0

0

0

,

0

0

0

;

l

a

t

e

r

d

a

t

a

h

a

v

e

b

e

e

n

r

e

s

c

a

l

e

d

a

c

c

o

r

d

i

n

g

l

y

.

7

Features of chronic inflation:

Fiscal imbalances are often less acute in the short

run than those observed during episodes of

hyperinflation; in this case more difficult to

mobilize political support for reform.

There is a high degree of inflation inertia resulting

from widespread indexation of wages and financial

assets.

The public is often skeptical of new attempts to

stop inflation, particularly when there is a history of

failed stabilization efforts.

Lack of credibility can be a source of inertia.

8

Fiscal Deficits, Seigniorage,

and Inflation

In countries where the tax collection system, capital

markets, and institutions are underdeveloped, fiscal

imbalances are often at the root of hyperinflation

and chronic inflation.

Governments often have no other option but to

monetize their budget deficits.

Bruno and Fischer (1990): how monetary growth

and fiscal deficits affect inflation.

Suppose: real money demand, md, is a function of

the expected inflation rate, a.

9

Under perfect foresight expected and actual

inflation rates are equal, = a.

Money demand:

md = m0exp(-).

At equilibrium, m = ms = md. This implies:

= - [ ln(m/m0)/ ].

Along an equilibrium path, inflation and real money

balances are negatively related.

Downward-sloping curve in the -m space,

10

denoted MM in Figure 5.2.

F

i

g

u

r

e

5

.

2

a

T

h

e

S

e

i

g

n

o

r

a

g

e

L

a

f

f

e

r

C

u

r

v

e

a

n

d

t

h

e

H

i

g

h

I

n

f

l

a

t

i

o

n

T

r

a

p

m

m

M

0

'

'

D

D

'D

m

H

B

F

A

D

'

'

m

D

'

(

d

=

d

)

A

A

D

m

L

B

'

M

C

L

m

a

x

H

11

F

i

g

u

r

e

5

.

2

b

T

h

e

S

e

i

g

n

o

r

a

g

e

L

a

f

f

e

r

C

u

r

v

e

a

n

d

t

h

e

H

i

g

h

I

n

f

l

a

t

i

o

n

T

r

a

p

m

=

d

A

A

m

d

A

B

B

'

d

*

A

L

m

a

x

H

12

Real fiscal deficit:

d = dA + ,

> 0,

dA: autonomous component of the deficit;

: measure Olivera-Tanzi effect (rise in the

inflation rate lowers the real value of tax revenue as

a result of the lag involved in collecting taxes).

Deficit must be financed by seigniorage revenue:

.

d = m,

M/M : rate of growth of the nominal money

stock.

13

Rate of change of real money balances:

.

m/m = - .

.

After substitution, in steady state with m/m = 0, =

:

= [dA /(m - )],

which implies that inflation and real money

balances are negatively related in equilibrium (DD

in figure 5.2).

14

Economy moves along MM in the short run; MM

intersects DD only when the economy reaches its

long-run equilibrium position (constant level of

real money balances).

Depending on the size of dA, MM and DD may or

may not intersect.

Figure 5.2 illustrates three cases:

two equilibria, corresponding to curve DD;

one equilibrium, corresponding to curve D´D´;

no equilibrium, corresponding to curve D´´D´´.

15

Under what conditions is the long-run equilibrium

unique?

Suppose = 0. In steady state, m = dA.

As dA increases, steady-state seigniorage revenue

(inflation tax) must increase as well.

But the relationship is nonlinear because as

inflation rises, real money demand falls.

Exponential form of the money demand function:

when inflation begins to rise, real money balances

fall by relatively little, and revenue from the inflation

tax increases at first.

As inflation continues to rise, real money balances

begin to fall at a rate faster than the rate at which

16

inflation rises.

Thus, after a phase during which m increases (at a

decreasing rate), it starts falling (at an increasing

rate) and eventually tends to zero as goes to

infinity.

These results define a concave relationship:

seigniorage Laffer curve associating the steadystate , and m = dA.

Figure 5.2: for some level of dA, there are two

corresponding rates of inflation, one low one high.

MM and DD curves in that case intersect twice.

Uniqueness occurs only at the optimal inflation

rate, max: maximizes steady-state seigniorage.

17

Revenue-maximizing rate of inflation is reached:

- [(dm/m)/(d/)] = m/ = 1.

m/: elasticity of real money demand with respect to

inflation.

Optimal inflation rate:

max = 1/,

: inflation elasticity of money demand.

18

Level of dAm in this case:

m

dA =

(m0exp(-1) - )/.

When < max, increases in raise revenue from

the inflation tax: ( d(m) / d > 0 and m/ < 1).

When > max, increases in decrease revenue

from the inflation tax: ( d(m) / d < 0 and m/ > 1).

Is the solution stable?

Equilibrium with a lower inflation rate is unstable.

19

This means that any disturbance or exogenous

shock will lead the economy away from low inflation

equilibrium point.

But, high inflation equilibrium is stable.

Given the nature of the adjustment process under

perfect foresight, a country can be stuck in a

situation in which inflation is persistently high:

inflation trap (Bruno and Fischer, 1990).

Any equilibrium characterized by > max is

inefficient: the same amount of revenue could be

collected at a lower inflation rate.

What can governments do to move the economy

away from an inefficient position?

20

Change either dA or , because both affect the

position of the economy along the seigniorage

Laffer curve.

For instance, a credible reduction in the money

growth rate may shift MM and DD in such a way

that the MM curve will intersect the DD curve only

once.

Figure 5.3: positive relation between inflation and

seigniorage.

Figure 5.4: positive relation between inflation and

broad money growth.

De Haan and Zelhorst (1990) and Karras (1994b):

link between monetary growth and budget deficits in

developing countries.

21

F

i

g

u

r

e

5

.

3

I

n

f

l

a

t

i

o

n

a

n

d

S

e

i

g

n

i

o

r

a

g

e

(

I

n

p

e

r

c

e

n

t

o

f

G

D

P

,

a

v

e

r

a

g

e

1

9

9

0

9

5

)

7

0

P

e

r

u

6

0

N

i

g

e

r

i

a

5

0

J

a

m

a

i

c

a

V

e

n

e

z

u

e

l

a

4

0

G

h

a

n

a

Z

i

m

b

a

b

w

e

T

a

n

z

a

n

i

a

A

l

g

e

r

i

a

C

ô

t

e

d

'

I

v

o

i

r

e

Inflatiocsumerpic

3

0

C

o

l

o

m

b

i

a

I

n

d

o

n

e

s

i

aP

C

o

s

t

a

R

i

c

a

h

i

l

i

p

p

i

n

e

s

2

0

I

n

d

i

a

K

o

r

e

a

B

o

l

i

v

i

a

P

a

k

i

s

t

a

n

1

0

N

e

p

a

l M

a

l

a

y

s

i

a

T

u

n

i

s

i

a

M

o

r

o

c

c

o

B

a

n

g

l

a

d

e

s

h T

h

a

i

l

a

n

d

C

h

i

l

e

0

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

S

e

i

g

n

i

o

r

a

g

e

S

o

u

r

c

e

:

W

o

r

l

d

B

a

n

k

.

22

F

i

g

u

r

e

5

.

4

I

n

f

l

a

t

i

o

n

a

n

d

M

o

n

e

y

G

r

o

w

t

h

(

I

n

p

e

r

c

e

n

t

p

e

r

a

n

n

u

m

,

a

v

e

r

a

g

e

o

v

e

r

1

9

8

0

9

5

)

4

0

N

i

g

e

r

i

a

V

e

n

e

z

u

e

l

a

3

0

T

a

n

z

a

n

i

a

J

a

m

a

i

c

a

C

o

l

o

m

b

i

a

Z

i

m

b

a

b

w

e

C

o

s

t

a

R

i

c

a

A

l

g

e

r

i

a

2

0

C

h

i

l

e

M

o

r

o

c

c

o

N

e

p

a

l

P

a

k

i

s

t

a

n

Inflatiocnsumerpics

G

h

a

n

a

P

h

i

l

i

p

p

i

n

e

s

1

0

I

n

d

i

a

C

ô

t

e

d

'

I

v

o

i

r

e

T

u

n

i

s

i

a

B

a

n

g

l

a

d

e

s

h

I

n

d

o

n

e

s

i

a

K

o

r

e

a

P

a

n

a

m

a

T

h

a

i

l

a

n

d

M

a

l

a

y

s

i

a

0

0

5

1

0

1

5

2

0

2

5

3

0

3

5

4

0

4

5

B

r

o

a

d

m

o

n

e

y

g

r

o

w

t

h

S

o

u

r

c

e

:

W

o

r

l

d

B

a

n

k

.

23

Conclusion: only in a small number of cases does a

close, positive relationship exist.

Explanation: role played by expectations about

future policy changes (Kawai and Maccini, 1990).

Criticism for public finance approach to

inflation:

Since

taxation is an alternative to money creation;

marginal cost of taxation is moderate relative to

the welfare costs of extreme inflation;

high money growth (and therefore high inflation) is

not optimal.

24

Other Sources of Chronic Inflation

In addition to fiscal deficits and money growth,

other factors that can affect the inflationary process

in the short run:

Wage inertia

Exchange rates and the terms of trade

The frequency of price adjustment

Food prices

Time inconsistency and the inflation bias

25

Wage Inertia

Backward-looking wage formation mechanisms

(e.g. wage indexation on past inflation rates) can

play an important role in inflation persistence.

Model: economy produces home goods and

tradable goods.

26

The inflation rate, , is given by a weighted

average of changes in prices of both categories of

goods:

= N + (1 - ) ( + *T)

0 < < 1,

: share of home goods in the price index,

N: rate of change in prices of home goods,

*T: rate of change in prices of tradables,

: devaluation rate.

27

Changes in prices of home goods are set as a

^ and the

mark-up over nominal wage growth, w,

level of excess demand for home goods, dN:

^ + d .

N = w

N

Nominal wage growth is determined through

indexation on past inflation as follows:

^ = 0 < 1,

w

-1

with = 1 denoting full indexation.

28

Inflation:

= -1+ dN + (1 - )( + *T),

inflation inertia exists as long as is positive.

Agénor and Montiel (1999): experience of countries

like Chile in the early 1980s and more recently

Brazil has shown that backward-looking wage

indexation can contribute to inflation inertia.

In some countries: frequency at which nominal

wages are adjusted tends to increase with the

inflationary pressures generated by exchange rate

movements.

29

Exogenous shocks in the wage bargaining

process could also exert independent impulse

effects on inflation.

This could persist over time in the presence of an

accommodative monetary policy.

30

Exchange rates and the terms of trade

Nominal exchange rate depreciation can exert

direct effects on the fiscal deficit through two

channels:

by affecting the domestic-currency value of

foreign exchange receipts by the government

and foreign exchange outlays;

by affecting the revenue derived from ad

valorem taxes on imports.

Since depreciation raises the prices of importcompeting goods and exportables, it may exert

pressure on wages due to its effect on the cost of

living.

31

This is likely to occur in a setting in which indexation

mechanisms are pervasive.

Example: a country facing a sharp deterioration in

competitiveness and a large current account deficit

and policymakers decide to devalue the exchange

rate.

Devaluation will increase both the domesticcurrency price of imported final goods as well as

imported inputs. This puts upward pressure on

domestic prices.

Increase in prices can be large enough to outweigh

the effect of the initial devaluation on

competitiveness---thereby prompting policymakers

to devalue again.

32

The process can therefore turn into a devaluationinflation spiral.

If wages are indexed on the cost of living, they will

increase also, putting further upward pressure on

prices of domestic goods.

Evidence: Onis and Ozmucur (1990) for Turkey;

Alba and Papell (1998) for Malaysia, the

Philippines, and Singapore.

Similar process can be seen in countries where the

official exchange rate is fixed but the parallel

market for foreign exchange is large.

Deterioration in external accounts leads agents to

expect a devaluation of the official exchange rate to

restore competitiveness.

33

Such expectations will be translated immediately

into a depreciation of the parallel exchange rate.

Because the parallel rate measures the marginal

cost of foreign exchange, domestic prices will tend

to increase.

This increase in prices will further erode

competitiveness, leading agents to expect an even

larger devaluation of the official exchange rate.

Figure 5.5: although parallel exchange rates display

a higher degree of variability than prices, the

correlation is positive in the case of Morocco and

Nigeria during the 1980s and early 1990s.

When the government is directly involved in

controlling exports of commodity, there may be: 34

S

o

u

r

c

e

s

:

I

n

t

e

r

n

a

t

i

o

n

a

l

M

o

n

e

t

a

r

y

F

u

n

d

.

Ja

J

n

a

8

J

n

1

a

8

J

n

4

a

8

J

n

7

a

9

- 40

- 30

- 20

- 10

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

M

a l

D

e

p

r

e

c

i

a

t

i

o

n

r

a

t

e

o

f

t

h

e

p

a

r

a

l

l

e

l

e

x

c

h

a

n

g

e

r

a

t

e

I

n

f

l

a

t

i

o

n

(

I

n

p

e

r

c

e

n

t

)

M

a

l

a

w

i

:

P

a

r

a

l

l

e

l

M

a

r

k

e

t

E

x

c

h

a

n

g

e

R

a

t

e

a

n

d

I

n

f

l

a

t

i

o

n

F

i

g

u

r

e

5

.

5

a

35

F

i

g

u

r

e

5

.

5

b

M

o

r

o

c

c

o

:

P

a

r

a

l

l

e

l

M

a

r

k

e

t

E

x

c

h

a

n

g

e

R

a

t

e

a

n

d

I

n

f

l

a

t

i

o

n

(

I

n

p

e

r

c

e

n

t

)

D

e

p

r

e

c

i

a

t

i

o

n

r

a

t

e

o

f

t

h

e

p

a

r

a

l

l

e

l

e

x

c

h

a

n

g

e

r

a

t

e I

n

f

l

a

t

i

o

n

60

Mo r

50

40

30

20

10

0

-1 0

-2 0

Ja

Ja

n8

Ja

n

1

8

Ja

n

4

8

Ja

n

7

9

S

o

u

r

c

e

s

:

I

n

t

e

r

n

a

t

i

o

n

a

l

M

o

n

e

t

a

r

y

F

u

n

d

.

36

F

i

g

u

r

e

5

.

5

c

N

i

g

e

i

a

:

P

a

r

a

l

l

e

l

M

a

r

k

e

t

E

x

c

h

a

n

g

e

R

a

t

e

a

n

d

I

n

f

l

a

t

i

o

n

(

I

n

p

e

r

c

e

n

t

)

D

e

p

r

e

c

i

a

t

i

o

n

r

a

t

e

o

f

t

h

e

p

a

r

a

l

l

e

l

e

x

c

h

a

n

g

e

r

a

t

e

300

I

n

f

l

a

t

i

o

n

N ig

250

200

150

100

50

0

-5 0

Ja

Ja

n8

Ja

n

1

8

Ja

n

4

8

Ja

n

7

9

S

o

u

r

c

e

s

:

I

n

t

e

r

n

a

t

i

o

n

a

l

M

o

n

e

t

a

r

y

F

u

n

d

.

37

direct effect of changes in the terms of trade on

the budget;

indirect effect through taxes on corporate profits

and domestic sales.

Reduction in government revenue due to negative

shock causes pressure for monetizing the fiscal

deficit.

Improvement in the terms of trade may lead to

higher inflation in the future:

if government spending has increased sharply in

response to temporary commodity price booms

and;

if such increases are difficult to reverse when

38

commodity prices fall.

The frequency of price adjustment

When high inflation is associated with highly

variable inflation and uncertainty over the pricing

horizon of price setters, the frequency of price

adjustment becomes endogenous and tends to

accelerate.

Shortening of the adjustment interval raises

inflation, leading to a further shortening of the

adjustment interval.

So price setters will be more and more opting to

denominate their prices in a foreign currency.

39

Dornbusch, Sturzenegger, and Wolf (1990):

increased synchronization between domestic

prices and the nominal exchange rate as inflation

rises in Bolivia, Israel, Argentina, and Brazil.

40

Food prices

In many developing countries food items comprise

the bulk of the goods included in consumer price

indices.

Consumer price index in Nigeria: food items

representing 69% of the total basket.

So supply-side factors affecting food prices have

an important effect on the behavior of prices.

Moser (1995): rainfall had a significant effect on the

rate of price increases, in addition to money growth

and exchange rate changes in Nigeria.

Figure 5.6: close correlation between inflation in

food prices and inflation in consumer prices.

41

F

i

g

u

r

e

5

.

6

I

n

f

l

a

t

i

o

n

a

n

d

F

o

o

d

P

r

i

c

e

s

(

I

n

p

e

r

c

e

n

t

p

e

r

a

n

n

u

m

,

a

v

e

r

a

g

e

o

v

e

r

1

9

8

0

9

5

)

4

0

N

i

g

e

r

i

a

G

h

a

n

a

3

0

T

a

n

z

a

n

i

a

V

e

n

e

z

u

e

l

a

C

o

l

o

m

b

i

a

J

a

m

a

i

c

a

Inflatiocnsumerpics

I

n

d

o

n

e

s

i

a C

o

s

t

a

R

i

c

a

B

a

n

g

l

a

d

e

s

h

2

0

Z

i

m

b

a

b

w

e

N

e

p

a

l

T

u

n

i

s

i

a

A

l

g

e

r

i

a

C

ô

t

e

d

'

I

v

o

i

r

e

C

h

i

l

e

T

h

a

i

l

a

n

d

P

h

i

l

i

p

p

i

n

e

s

I

n

d

i

a

1

0

M

a

l

a

y

s

i

a

M

o

r

o

c

c

o

K

o

r

e

a

P

a

n

a

m

a

0

0

1

0

2

0

3

0

4

0

I

n

f

l

a

t

i

o

n

i

n

f

o

o

d

p

r

i

c

e

s

S

o

u

r

c

e

:

W

o

r

l

d

B

a

n

k

.

42

Time inconsistency

and the inflation bias

Lack of credibility may impart an inflation bias to

monetary policy.

This lack of credibility may result from the time

inconsistency problem faced by policy

announcements: a policy that is optimal ex ante

may no longer be optimal ex post.

Reason: policymakers are concern about inflation

as a policy goal and with the fact that inflation may

carry benefits.

43

Barro and Gordon (1983): policymakers are

concerned about both inflation and

unemployment, with a loss function:

L = (1/2)(y -

~2

y) +

~ 2,

(/2)( - )

> 0,

(13)

~

y: current output, y: its desired level,

~ desired inflation rate,

: actual inflation, :

: relative importance of deviations of inflation from

its target value in the loss function.

44

Expectations-augmented Phillips curve:

y = yL + ( -

a)

+ u,

~

> 0, yL < y

(14)

yL: long-term level of output,

a: expected inflation,

u: disturbance term with zero mean and constant

variance,

~ ensures that the policymakers have an

yL < y:

incentive to raise output above its long-run value.

45

Policymakers want private agents to expect low

inflation, in order to exploit a favorable trade-off

between inflation and output.

But the mere announcement of a policy of low

inflation is not credible, because policymakers have

an incentive to renege to increase output and

reduce unemployment and private agents

understand this renege.

Result:

inflation will in equilibrium be higher than it would be

otherwise;

monetary policy suffers from an inflation bias.

46

Substitute (14) in (13):

L=(1/2) {yL + ( ~ 2

+ (/2)( - )

a)

~

- y + u}2

(15)

With a binding commitment to low inflation, = a;

the loss function becomes:

~ 2.

L = (1/2)(yL - y~ + u)2 + (/2)( - )

47

Under discretion, policymakers take expected

inflation as given; the first-order condition for

minimizing the expected value of (15) with respect

to is:

~

~

=+

(y - yL)

+

2

+

~

2

a

( - )

+ 2

In equilibrium, = a (Phillips curve) :

= + (y - yL)/.

~

~

48

In equilibrium output can deviate from its capacity

level only as a result of random shocks:

y = yL + u.

Under discretion, the equilibrium inflation rate will

be higher than desired inflation.

~

The higher (y - yL), the higher the slope of the

Phillips curve, and the lower the relative

importance of inflation in the loss function, the

higher inflation will be.

49

Credible commitment to a policy rule is welfare

enhancing compared with a discretionary policy.

If policymakers can credibly commit themselves to

low inflation, the economy will be better off; output

will be the same as in the discretionary policy case

but inflation will be lower.

50

Nominal Anchors in

Disinflation: Money vs. the

Exchange Rate

Controllability and Effectiveness

Adjustment Paths and Relative Costs

Credibility, Fiscal Commitments, and Flexibility

The Flexibilization Stage

51

Debated issues in the analysis of disinflation

policies: relative merits of exchange-rate-based

stabilization versus the targeting of money (or

credit) growth in conjunction with exchange rate

flexibility.

When information is complete and no distortions or

rigidities are present, exchange-rate targets or

monetary targets are equivalent policies under

perfect capital mobility.

Fischer (1986): when there are multiperiod

nominal contracts, exchange-rate targets

dominate monetary targets under some

configurations of the underlying parameters.

52

Agénor and Montiel (1999): under imperfect capital

mobility, disinflation through a reduction in the

nominal devaluation rate or a fall in the rate of

growth of domestic credit are not equivalent.

Choice between the exchange rate and the

money supply as a nominal anchor depends on

three main considerations:

degree of controllability and the effectiveness of

the instrument in bringing down inflation;

adjustment path of the economy and the relative

costs associated with each instrument;

degree of credibility that each instrument

commands, and its relationship with fiscal policy.

53

Controllability and Effectiveness

Policymakers cannot control directly the money

supply, but fixing the exchange rate can be done

relatively fast and without substantial costs.

When money demand is subject to large random

shocks and velocity is unstable, the effectiveness

of the money supply as an anchor is reduced.

But an exchange rate peg will anchor the price level

through its direct impact on prices of tradables.

So fixing the exchange rate rather than the money

stock may appear preferable.

54

Monitorable target may bolster the government's

commitment to the stabilization effort and help to

move new low-inflation equilibrium (Bruno, 1991).

Policymakers must be able to convince private

agents that they are willing and able to defend the

fixed exchange rate.

Exchange rate management may be difficult to

achieve if the current account deficit is large or if

official reserves are relatively low.

Speculative attacks may occur.

55

Adjustment paths and relative costs

Money-based and exchange-rate-based

stabilization programs differ significantly.

Calvo and Végh (1993):

Exchange-rate-based stabilization programs lead to

an initial expansion and a recession later on.

Money-based programs cause initial contraction

in output.

Former pattern: boom-recession cycle since

credibility of the stabilization program is low and

perceived as temporary.

Agents, to take advantage of temporarily low prices

of tradable goods, increase spending.

56

Result: current account deficit and real exchange

rate appreciation by forcing the authorities

eventually to abandon the attempt to fix the

exchange rate.

Weak evidence in favor of large intertemporal

substitution effects.

Reinhart and Végh (1995): it can explain the

behavior of consumption for some of the programs

implemented in the 1980s, but not for the tablita

experiments of the 1970s in Argentina, Chile, and

Uruguay.

Nominal interest rates would have had to fall more

than they did to account for a sizable fraction of the

consumption boom recorded in the data.

57

Intertemporal effects were not large enough to

explain the pattern of output.

Interactions between monetary and supply-side

factors.

Roldós (1995):

Due to cash-in-advance constraint, inflation

creates a wedge between the real rate of return on

foreign-currency-denominated assets and domesticcurrency-denominated assets.

When stabilization program based on a permanent

reduction in the devaluation rate reduces the wedge

and leads to an increase in the desired capital stock

in the long run.

58

In the short run, consumption and investment

increase, causing a real appreciation, a current

account deficit, and an increase in output of home

goods.

Over time, the increase in output of tradable goods

lowers the initial current account deficit.

Not predict a recession at a later stage.

Rebelo and Végh (1997):importance of supply-side

factors (real wages).

How do the relative costs of money-based and

exchange-rate-based programs relate to their

implications for remonetization?

59

Pegged-exchange rate system:

Households and enterprises increase their real

money balances after a period of high inflation.

Increase is satisfied automatically through the

balance of payments, as agents repatriate their

capital held abroad and convert it costlessly into

domestic currency.

Money supply anchor:

No automatic mechanism for agents to rebuild their

real money balances.

Many central banks refrain from domestic credit

expansion, and the economy remains

undermonetized; high real interest rates and an

60

overvalued currency.

Result: successful anti-inflation programs under a

money supply target (and floating exchange rates)

tend to be more contractionary than under pegged

exchange rates.

61

Credibility, Fiscal Commitment,

and Flexibility

Degree of credibility of the money supply and the

exchange rate is important in choosing a nominal

anchor.

Credibility depends on:

policymakers' ability to convey clear signals about

their policy preferences;

degree of controllability of policy instruments and

the dynamic adjustment path of the economy, as

discussed earlier.

62

Public observability of the exchange rate as

opposed to monetary and credit aggregates

enhances the credibility of an exchange rate

anchor.

Money-based stabilization by an immediate

recession may lose credibility rapidly, if the shortterm output and employment cost is high.

When the exchange rate is used as a nominal

anchor, residual inflation in home goods prices

may remain high combined with the expansion of

aggregate demand, it may lead to a real

appreciation.

This immediately weakens the credibility.

63

When lack of credibility is pervasive, the choice

between money and the exchange rate may not

matter; inflation will remain high regardless of the

anchor.

An exchange-rate rule is, however, more successful

in reducing inflation if there is some degree of

credibility; initial expansion and the upward

pressure on the real exchange rate will be

dampened.

Exchange rate anchor may induce a higher

commitment to undertake stabilization measures:

fiscal adjustment.

64

If there are doubts about the government's

commitment to fiscal restraint, an exchange rate

peg would also lack credibility.

Végh (1992): ten exchange-rate-based programs

aimed at stopping high chronic inflation.

Seven of them were failures:

Two cases: failure was due to real appreciation of

the currency following slow convergence of

inflation, in spite of achieving fiscal balance.

Remaining five: failure to implement a lasting

fiscal adjustment was the main factor.

65

Flexibilization stage

Although a pegged exchange rate is beneficial in

stopping high inflation, maintaining it for too long

can become problematic.

Fixed nominal exchange rate, continued inflation

higher than that prevailing in trading partners

implies an appreciation of the real exchange rate

erode external competitiveness and hinder export.

Deteriorating trade performance may force the

authorities to depreciate the exchange rate and

reignite inflationary pressures.

66

Shift toward a more flexible exchange rate regime

once macroeconomic stability is achieved, is

important to adjust to internal and external shocks.

Reduced commitment to low inflation must be

renewed by fiscal and monetary discipline to

maintain credibility.

67

Disinflation Programs:

The Role of Credibility

Sources of Credibility Problems

Enhancing Credibility

Big Bang and Gradualism

Central Bank Independence

Price Controls

Aid as a Commitment Mechanism

68

Sources of credibility problems

Four different sources of credibility problems in

disinflation programs:

Inconsistency between the objective of

disinflation and the policy instruments to achieve

this objective, or sequencing of policy measures in

a reform program.

Uncertainty associated with the policy environment

and exogenous shocks.

Time inconsistency of policy announcements:

program is optimal ex ante may not be ex post.

Incomplete or asymmetric information about

policymakers' preferences.

69

Over time private agents will get to believe that

policymakers are serious about their policy goal

(learning process).

If policymakers have a long tradition of stop-and-go

policies and the rotation of policymakers in office

tends to be high, learning process will be slow.

Imperfect monitoring capability makes building

reputation by policymakers more difficult; private

agents may learn only gradually, through a

backward-induction process.

70

Agénor and Taylor (1992): two methods for

assessing the relative importance of the various

sources of lack of credibility.

Specify a model of the inflationary process in which

lagged inflation appears and estimate it with

recursive least-squares techniques:

changes in the behavior of the coefficient of the

lagged inflation rate (inertia or persistence) can

be used to assess changes in the degree of

credibility;

increased credibility will translate into a lower

coefficient.

71

Study of changes in the behavior of the coefficient

of a variable measuring the opportunity cost of

holding domestic money.

Assumption: increased credibility will translate into a

lower degree of persistence in the inflationary

process and in a shift toward domestic-currencydenominated assets.

72

Enhancing credibility

Four ways:

adoption of a drastic (big bang) program as a way

to signal the policymaker's commitment to

disinflation;

central bank independence;

imposition of price controls;

conditional foreign assistance.

73

Big bang and gradualism

Early phase of overadjustment as a means to

signal to skeptical agents the policymakers'

commitment to inflation stabilization.

Easier to implement in countries where a new

government with a broad anti-inflation mandate is

just being put in place.

Although initial costs of a big bang program is

high, it may be less than the costs of inflation

continuing at a higher level for a long period of time.

Adopting an overly tight policy stance may

exacerbate it because it may create expectations of

future policy reversals.

74

Such expectations may result from the

conjunction of two factors:

large short-run output and employment costs and a

consequent loss of political support;

fact that the future benefits of disinflation are

heavily discounted by the public.

In such conditions, enhancing the credibility may

require to implement politically and economically

sustainable measures instead of shock therapy.

75

Central bank independence

Independence may be critical in countries where

central bank financing of government budget

deficits is often the main source of inflation.

Factors that may mitigate the credibility gain by

central bank independence:

Legal independence does not guarantee the

absence of freedom from political interference and

pressure on the central bank's policy decisions.

Blackburn and Christensen (1989): even an

independent central bank may be willing to make

concessions to the government in order to retain its

autonomy.

76

Adhering to a rigid anti-inflation policy stance

implemented by an independent central bank may

be suboptimal in an economy subject to adverse

economic shocks.

Credibility of monetary policy may depend on the

overall stance of macroeconomic policy, rather

than on the degree of central bank independence

per se.

Independent monetary and fiscal authorities may

adopt policies that generate coordination

problems and costs that may outweigh the gain

resulting from central bank autonomy alone.

77

Alesina and Tabellini (1990):

Ambiguity of the net benefits from central bank

precommitment to low inflation.

Reason: lower inflation reduces the revenue from

inflationary finance and forces the fiscal authority to

resort to a higher level of distortionary taxation.

Early empirical studies focusing mostly on

industrial countries: whenever central banks had

the highest degree of autonomy also had the lowest

levels of inflation.

78

Measuring central bank independence

(Cukierman, 1992):

appointment mechanisms for the governor and

board of directors;

turnover of central bank governors;

approval mechanism for conducting monetary policy

statutory requirements of the central bank regarding

its basic aim and financing of the budget deficit

existence of a ceiling on total government borrowing

from the central bank.

79

Recent empirical literature: no robust association

between central bank independence and inflation

performance in industrial countries (Forder (1998)).

Sikken and De Haan (1998):

For developing countries.

Measuring central bank independence using

various indicators:

Synthetic legal measure (Cukierman, 1992):

variables related to the appointment, dismissal,

and term of office of the governor of the central

bank;

80

variables related to the resolution of conflicts

between the executive branch and the central

bank over monetary policy and the participation

of the central bank in the budgetary process;

final objectives of the central bank, as stated in

its charter;

legal restrictions on the ability of the public sector

to borrow from the central bank.

Turnover rate of central bank governors, which

attempts to capture actual independence.

Political vulnerability index: fraction of political

transitions that are followed within six months by a

replacement of the central bank governor.

81

Sikken and de Haan: no evidence that central bank

independence creates an incentive for governments

to maintain low fiscal deficits.

Found: measures of independence are not clearly

related to the degree of monetization of government

budget deficits by the central bank.

82

Price controls

Case when inflationary process is characterized by

substantial inertia, stemming from explicit or

implicit indexation.

This is a common feature of economies suffering

from chronically high inflation.

Arguments in favor of temporary price controls

(Dornbusch, Sturzenegger, and Wolf , 1990):

Realignment device: when pricing decisions are

not instantaneous, price controls may help realign

prices quickly and correct price distortions.

Coordination device: price controls help

coordinate expectations toward a low inflation

83

path.

Fiscal device: Reverse Olivera-Tanzi effect:

transition from high to low inflation yields an

immediate gain in real revenue from taxation.

Lower the borrowing needs of the government

from the central bank.

Price controls may help enhance credibility by

serving as an additional nominal anchor.

Blejer and Liviatan (1987): price controls may give

policymakers some breathing room.

Persson and van Wijnbergen (1993): price controls

may help policymakers to reduce the cost of

signaling their commitment to low inflation.

84

Successful temporary application of price

controls: Israeli stabilization of 1985.

All nominal variables, including the exchange rate,

were frozen.

With a sharp fiscal contraction and a restrictive

monetary policy, price controls led to a quick

reduction in inflation and enhanced government

credibility, without a severe economic contraction.

Criticism of price controls:

Use of price controls may be counterproductive

because they do not enable the public to learn

whether inflation has really been stopped.

85

Credibility-enhancing effect of price controls may

vanish if policymakers are unwilling or unable to

control all prices in the economy (Agénor, 1995).

In this case price controls may lead to inflation

inertia.

Problems at the practical level:

Price controls have often been used as a

substitute, rather than a complement to fiscal and

monetary adjustment.

Repeated use of price controls diminished their

effectiveness, as economic agents anticipated the

price increases that would follow the flexibilization

stage.

86

Aid as a commitment mechanism

Enhance credibility and the probability of program

success by subjecting to an external enforcement

agency whose commitment to low inflation is well

established (e.g. IMF).

They provide foreign assistance conditional on

attaining specific macroeconomic policy targets.

Difficulties arise in judging the credibilityenhancing effect of foreign assistance:

Political considerations often play a role in

deciding whether particular countries should receive

external financial assistance support.

87

Conditionality is a double-edged sword. If the

degree of conditionality attached to foreign aid is

perceived to be excessive, uncertainty about

external support may rise (Orphanides (1996)).

88

Two Recent stabilization

Experiments

Egypt, 1992-97

Uganda, 1987-95

Egypt: exchange-rate-based stabilization.

Uganda: money-based approach.

Both show the role of fiscal adjustment in

stabilization programs.

89

Egypt, 1992-97

Macroeconomic imbalances faced by Egypt

(Figure 5.7):

Although inflation was not high, the fiscal deficit and

money growth rate were high.

Dollarization ratio (share of foreign currency

deposits in total bank deposits) grew to about 46%

in 1990.

Depreciation of about 30% between 1986 and 1991

of the real effective exchange rate.

Current account deficit reached about 10% in

1990/91.

90

F

i

g

u

r

e

5

.

7

a

E

g

y

p

t

:

M

a

c

r

o

e

c

o

n

o

m

i

c

I

n

d

i

c

a

t

o

r

s

,

1

9

8

7

9

6

(

I

n

p

e

r

c

e

n

t

p

e

r

a

n

n

u

m

,

u

n

l

e

s

s

o

t

h

e

r

w

i

s

e

i

n

d

i

c

a

t

e

d

)

7

l

i

z

a

r

B

Re a

l

G

DP

M

o

n

e

y

,

c

r

e

d

i

t

,

a

n

d

p

r

i

c

e

s

6

3

0

5

4

g

D

o

m

e

s

t

i

c

c

r

e

d

i

t

g

r

o

w

t

h

B

r

o

a

d

m

o

n

e

y

g

r

o

w

t

h

2

0

I

n

f

l

a

t

i

o

n

3

2

1

0

1

0

0

19

1

8

9

1

8

9

9

1

0

9

9

1

2

9

9

4

96

1

9

8

8

1

9

9

01

9

9

2

1

9

9

41

9

9

6

S

o

u

r

c

e

:

I

n

t

e

r

n

a

t

i

o

n

a

l

M

o

n

e

t

a

r

y

F

u

n

d

.

91

F

i

g

u

r

e

5

.

7

b

E

g

y

p

t

:

M

a

c

r

o

e

c

o

n

o

m

i

c

I

n

d

i

c

a

t

o

r

s

,

1

9

8

7

9

6

(

I

n

p

e

r

c

e

n

t

p

e

r

a

n

n

u

m

,

u

n

l

e

s

s

o

t

h

e

r

w

i

s

e

i

n

d

i

c

a

t

e

d

)

5

C

u

r

r

e

n

t

a

c

c

o

u

n

t

(

i

n

%

G

D

P

)

6

0

D

o

l

l

a

r

i

z

a

t

i

o

n

r

a

t

i

o

2

/

(

i

n

p

e

r

c

e

n

t

)

5

0

0

4

0

5

3

0

2

0

1

0

O

v

e

r

a

l

l

f

i

s

c

a

l

b

a

l

a

n

c

e

,

e

x

c

.

o

f

f

i

c

i

a

l

g

r

a

n

t

s

(

i

n

%

G

D

P

)

1

0

1

5

0

1

9

8

81

9

9

01

9

9

21

9

9

41

9

9

6

1

9

8

81

9

9

01

9

9

21

9

9

41

9

9

6

S

o

u

r

c

e

:

I

n

t

e

r

n

a

t

i

o

n

a

l

M

o

n

e

t

a

r

y

F

u

n

d

.

2

/

U

.

S

.

d

o

l

l

a

r

d

e

p

o

s

i

t

s

i

n

p

e

r

c

e

n

t

o

f

t

o

t

a

l

d

e

p

o

s

i

t

s

.

92

F

i

g

u

r

e

5

.

7

c

E

g

y

p

t

:

M

a

c

r

o

e

c

o

n

o

m

i

c

I

n

d

i

c

a

t

o

r

s

,

1

9

8

7

9

6

(

I

n

p

e

r

c

e

n

t

p

e

r

a

n

n

u

m

,

u

n

l

e

s

s

o

t

h

e

r

w

i

s

e

i

n

d

i

c

a

t

e

d

)

3

5

T

o

t

a

l

d

e

b

t

s

e

r

v

i

c

e

/

e

x

p

o

r

t

s

o

f

g

o

o

d

s

a

n

d

s

e

r

v

i

c

e

s

130

N

o

m

i

n

a

l

e

f

f

e

c

t

i

v

e

e

x

c

h

a

n

g

e

r

a

t

e

3

/

120

3

0

110

2

5

100

2

0

T

o

t

a

l

d

e

b

t

s

e

r

v

i

c

e

/

G

N

P

90

1

5

80

R

e

a

l

e

f

f

e

c

t

i

v

e

e

x

c

h

a

n

g

e

r

a

t

e

3

/

1

0

70

5

60

0

50

19

1

8

9

1

8

9

9

1

0

9

9

1

2

9

9

4

9

1

9

8

81

9

9

01

9

9

21

9

9

41

9

9

6

S

o

u

r

c

e

:

I

n

t

e

r

n

a

t

i

o

n

a

l

M

o

n

e

t

a

r

y

F

u

n

d

.

3

/

1

9

9

0

=

1

0

0

;

a

r

i

s

e

i

s

a

d

e

p

r

e

c

i

a

t

i

o

n

.

93

Gross external debt increased to 147% of GDP

during the period 1988/89-1990/91.

Program of macroeconomic stabilization and

structural reform was implemented in 1991.

Key features:

combination of fiscal, monetary, and credit policies

together with an exchange rate anchor policy which

was viewed as a way of:

signaling the government's commitment to

disinflate;

limiting pass-through effects of nominal

exchange rate changes on prices.

94

Substantial adjustment of fiscal accounts

through:

general sales tax was introduced and a global

income tax reform was implemented;

domestic-currency value of oil revenues and Suez

Canal receipts as well as taxes on imports

increased;

cuts in public expenditure;

debt forgiveness and rescheduling agreement.

95

Results:

overall deficit of the government declined sharply;

primary fiscal balance of the government improved;

gross domestic public debt fell;

sharp reduction in broad money growth;

rate of inflation declined;

improvement in external accounts and a substantial

accumulation of foreign reserves;

appreciation of real effective exchange rate;

dollarization ratio fell.

96

Output cost of disinflation was a short-lived

recession: real GDP growth dropped to 1.1% in

1990/91 but rebounded to 4.6% in 1994/95 and 5%

on average for 1995/96-1996/97.

This reflected two factors:

Real credit growth to the nongovernment sector

remained positive throughout the stabilization

program.

Although interest rates were liberalized in early

1991 and jumped to high levels, they went down

very quickly.

97

Key lessons:

Importance of fiscal adjustment and external

factors.

Debt reduction and write-offs contributed to

significantly to fiscal adjustment and improvements

in the country's external accounts---despite an

appreciating real exchange rate.

Tighter policies, with a potentially higher output

cost, would have been needed otherwise if the

external constraint had been more severe.

External assistance played an essential role in

helping the program gain credibility rapidly.

98

Uganda, 1987-95

Economic problems before applying the

program:

In 1986, per capita GDP was estimated to be at

about 50% below the level of 1970.

Inflation was high.

Fixed exchange rate regime led to a significant real

appreciation and a loss of competitiveness.

Foreign exchange shortages led to a considerable

spread between the official exchange rate and the

parallel market exchange rate.

Deterioration in terms of trade.

99

In 1987: structural adjustment package, Economic

Recovery Program, was applied.

Stabilization took place through a tightening of

monetary and fiscal policies.

Currency depreciation was accompanied by a

substantial increase in producer prices.

Import restrictions were removed.

GDP growth responded quickly to the adjustment

measures (Figure 5.8).

But inflation remained high.Main factors behind this

result:

insufficient effort to tighten fiscal policy;

excessive growth of bank credit to the

100

government.

F

i

g

u

r

e

5

.

8

a

U

g

a

n

d

a

:

M

a

c

r

o

e

c

o

n

o

m

i

c

I

n

d

i

c

a

t

o

r

s

,

1

9

8

7

9

5

1

/

(

I

n

p

e

r

c

e

n

t

p

e

r

a

n

n

u

m

,

u

n

l

e

s

s

o

t

h

e

r

w

i

s

e

i

n

d

i

c

a

t

e

d

)

1

0

R

e

a

l

G

D

P

g

r

o

w

t

h

8

2

5

0

2

0

0

1

5

0

I

n

f

l

a

t

i

o

n

6

1

0

0

B

r

o

a

d

m

o

n

e

y

g

r

o

w

t

h

4

5

0

2

0

1

9

8

7

1

9

8

9

1

9

9

1

1

9

9

3

1

9

9

5 1

9

8

7

1

9

8

9

1

9

9

1

1

9

9

3

1

9

9

5

S

o

u

r

c

e

:

S

h

a

r

e

r

e

t

a

l

.

(

1

9

9

5

)

,

I

n

t

e

r

n

a

t

i

o

n

a

l

M

o

n

e

t

a

r

y

F

u

n

d

a

n

d

W

o

r

l

d

B

a

n

k

.

1

/

D

a

t

a

r

e

f

e

r

t

o

t

h

e

f

i

s

c

a

l

y

e

a

r

(

J

u

l

y

1

J

u

n

e

3

0

)

e

x

c

e

p

t

f

o

r

e

x

c

h

a

n

g

e

r

a

t

e

s

.

1

9

8

8

,

f

o

r

i

n

s

t

a

n

c

e

,

r

e

f

e

r

s

t

o

1

9

8

7

/

8

8

.

101

F

i

g

u

r

e

5

.

8

b

U

g

a

n

d

a

:

M

a

c

r

o

e

c

o

n

o

m

i

c

I

n

d

i

c

a

t

o

r

s

,

1

9

8

7

9

1

5

/

(

I

n

p

e

r

c

e

n

t

p

e

r

a

n

n

u

m

,

u

n

l

e

s

s

o

t

h

e

r

w

i

s

e

i

n

d

i

c

a

t

e

d

)

5

F

i

s

c

a

l

b

a

l

a

n

c

e

(

i

n

%

G

D

P

)

1

5

0

T

o

t

a

l

d

o

m

e

s

t

i

c

c

r

e

d

i

t

g

r

o

w

t

h

0

1

0

0

G

o

v

e

r

n

m

e

n

t

c

r

e

d

i

t

g

r

o

w

t

h

5

5

0

1

0

1

5

C

u

r

r

e

n

t

a

c

c

o

u

n

t

b

a

l

a

n

c

e

(

i

n

%

G

D

P

)

0

2

0

5

0

1

9

8

7

1

9

8

9

1

9

9

1

1

9

9

3

1

9

9

5

1

9

8

7

1

9

8

9

1

9

9

1

1

9

9

3

1

9

9

5

S

o

u

r

c

e

:

S

h

a

r

e

r

e

t

a

l

.

(

1

9

9

5

)

,

I

n

t

e

r

n

a

t

i

o

n

a

l

M

o

n

e

t

a

r

y

F

u

n

d

a

n

d

W

o

r

l

d

B

a

n

k

.

1

/

D

a

t

a

r

e

f

e

r

t

o

t

h

e

f

i

s

c

a

l

y

e

a

r

(

J

u

l

y

1

J

u

n

e

3

0

)

e

x

c

e

p

t

f

o

r

e

x

c

h

a

n

g

e

r

a

t

e

s

.

1

9

8

8

,

f

o

r

i

n

s

t

a

n

c

e

,

r

e

f

e

r

s

t

o

1

9

8

7

/

8

8

.

102

F

i

g

u

r

e

5

.

8

c

U

g

a

n

d

a

:

M

a

c

r

o

e

c

o

n

o

m

i

c

I

n

d

i

c

a

t

o

r

s

,

1

9

8

7

9

5

1

/

(

I

n

p

e

r

c

e

n

t

p

e

r

a

n

n

u

m

,

u

n

l

e

s

s

o

t

h

e

r

w

i

s

e

i

n

d

i

c

a

t

e

d

)

1

2

0

2

5

0

1

0

0

T

o

t

a

l

d

e

b

t

(

i

n

%

o

f

G

N

P

)

2

0

0

D

e

b

t

s

e

r

v

i

c

e

(

i

n

%

o

f

e

x

p

o

r

t

s

o

f

g

o

o

d

s

a

n

d

s

e

r

v

i

c

e

s

)

8

0

N

o

m

i

n

a

l

e

f

f

e

c

t

i

v

e

e

x

c

h

a

n

g

e

r

a

t

e

2

/

1

5

0

6

0

1

0

0

R

e

a

l

e

f

f

e

c

t

i

v

e

e

x

c

h

a

n

g

e

r

a

t

e

2

/

4

0

2

0

0

1

9

8

7

1

9

8

9

1

9

9

1

1

9

9

3

1

9

9

5

5

0

0

1

9

8

7

1

9

8

9

1

9

9

1

1

9

9

3

1

9

9

5

S

o

u

r

c

e

:

S

h

a

r

e

r

e

t

a

l

.

(

1

9

9

5

)

,

I

n

t

e

r

n

a

t

i

o

n

a

l

M

o

n

e

t

a

r

y

F

u

n

d

a

n

d

W

o

r

l

d

B

a

n

k

.

1

/

D

a

t

a

r

e

f

e

r

t

o

t

h

e

f

i

s

c

a

l

y

e

a

r

(

J

u

l

y

1

J

u

n

e

3

0

)

e

x

c

e

p

t

f

o

r

e

x

c

h

a

n

g

e

r

a

t

e

s

.

1

9

8

8

,

f

o

r

i

n

s

t

a

n

c

e

,

r

e

f

e

r

s

t

o

1

9

8

7

/

8

8

.

2

/

1

9

9

0

=

1

0

0

;

a

r

i

s

e

i

s

a

d

e

p

r

e

c

i

a

t

i

o

n

.

103

Lack of fiscal adjustment and price stabilization and

an improvement in external accounts reflected:

maintenance of an overvalued exchange rate;

difficult external environment.

Major deterioration in terms of trade during