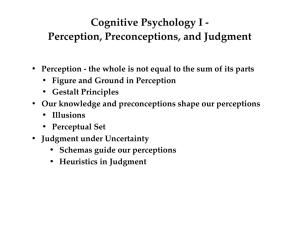

Sometimes schemas can get us into trouble

advertisement

Schemas and Heuristics “Please your majesty,” said the knave, “I didn’t write it and they can’t prove I did; there’s no name signed at the end.” “If you didn’t sign it,” said the King, “that only makes matters much worse. You must have meant some mischief, or else you’d have signed your name like an honest man.” –Lewis Carroll Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland • Quote illustrates how beliefs might persevere, even in the face of contradictory evidence (the perseverance effect discussed last time) • We’ll continue talking about schemas and mental shortcuts today Sometimes schemas can get us into trouble • Confirmation biases: Tendencies to interpret, seek, and create information that verifies our preexisting beliefs or schemas. • Examples of confirmation biases – Belief perseverance: The tendency to maintain beliefs, even after they have been discredited. Perseverance Effect • Ross et al. (1975) • IV: Success, failure, or average feedback about ability to detect “real” or “fake” suicide notes • Intervention: E explained feedback was randomly assigned (discredited belief) • DV: Estimated how well would actually do at task • Results: Beliefs persevered. Estimates closely matched false feedback Ps had received. • Why? May think of reasons to support…takes on life of its own. Confirmation bias • Our expectations also can influence how we go about obtaining new information about another person. • Imagine that you are going to meet a friend of a friend. Your friend tells you that his friend, Dana, is very outgoing and friendly, the life of the party. When you meet Dana and are getting acquainted, will that information influence what you say and do? Some work suggests that it will. Confirming Prior Expectations • Snyder & Swann, 1978 • IV: Expectations about person to be interviewed: introverted vs. extraverted • DV: Selection of interview questions. Slanted toward extraverted (How do you liven things up at a party?), introverted (Have you ever felt left out of some social group?), or neutral. • Results: Ps asked loaded questions that confirmed their prior expectations On being sane in insane places • David Rosenhan • +7 colleagues gained admission to mental hospitals • “heard voices,” false name, all else true • Example of confirmation bias • Stayed in hospital average of 19 days • Most needed outside help to get out • Read description of Tom W. • Are clinicians exempt from bias? How might this apply to a clinician’s diagnosis? • Clinicians might look for information that confirms their diagnosis and ignore information that might disconfirm it. (Example: “On being sane in insane places” Rosenhan) Confirmation Bias in the Clinic • Once we have a hypothesis, it’s easy to look for confirming evidence. – True for clinicians, psychiatrists, etc. – True in other contexts • Courtroom: Lawyer or witness makes inappropriate statement. Judge tells jury, “Disregard the evidence.” Self-fulfilling Prophecy • One person’s expectations can affect the behavior of another person. • Self-fulfilling prophecy: The process whereby (1) people have an expectation about another person, which (2) influences how they act toward that person, which (3) leads the other person to behave in a way that confirms people’s original expectations. Example • I expect that the students in the front row are especially smart. • I may give them more attention, nod, smile, and notice when they ask questions. • As a consequence, students in the front row might pay closer attention, ask more questions, etc., thereby confirming my expectation. Teacher expectations • Rosenthal & Jacobson (1968) • Discussion Limits of Self-fulfilling prophecies • Self-fulfilling prophecies are – MORE likely to occur when the interviewer is distracted (tired, under time constraints, etc.) – LESS likely to occur when the interviewer is motivated to be accurate Heuristics • Specific processing rules (or rules of thumb) Mental Shortcuts or Heuristics • Judgmental heuristics: Mental shortcuts (rules of thumb) people use to make judgments quickly and efficiently • Research on heuristics arose in response to a view of humans as rational, thoughtful decision-makers. – Economists’ models – Tversky & Kahneman – Nisbett & Ross • We will discuss a few specific heuristics (but there are many) What is the difference between a schema and a heuristic? • Schema – organized set of knowledge in a given domain (knowledge structure) – influences processing – Ex: Rude person – related traits, expected behaviors, expectations about own reactions, etc. • Mental shortcut – – – – Specific processing rule Not necessarily tied to a particular schema Not a “knowledge structure” Ex: If an item is expensive, it must be good quality. • Exercise Representativeness heuristic • The tendency to assume, despite compelling odds to the contrary, that someone belongs to a group because he/she resembles a typical member of that group. Base-rate information • Are there more salespeople or librarians in the population? • If knew that sample = 100 people and 70 were salespeople and 30 librarians, what would you have guessed? • Representativeness heuristic can lead us to discount important base-rate information (i.e., info about the frequency of members of different categories in the population) Availability Heuristic • The tendency to perceive events that are easy to remember as more frequent and more likely to happen than events than are more difficult to recall. • Which of the following are more frequent causes of death in the U.S.? – Homicide vs. diabetes? – Flood vs. infectious hepatitis – Tornados or asthma? People often give too much weight to vivid, memorable information. • Hamill, Nisbett, & Wilson (1980) • IV: Type of information • Vivid, concrete atypical + statistical • Vivid, concrete typical + statistical • Control group (no information) • DV: Positivity/negativity of attitudes toward welfare recipients in general • Results: Participants who read the vivid stories with either the “atypical” or “typical” label, expressed more UNFAVORABLE attitudes toward welfare mothers in general than those in the control group. Counterfactual Thinking • We mentally change some aspect of the past as a way of imagining what might have been. Study of Counterfactual Thinking (Medvec, Madey, & Gilovich, 1995) • Videotaped 41 athletes in the 1992 summer Olympic Games who had won a silver or bronze metal. • Quasi-IV: Athlete won silver OR bronze medal • DV: Judges’ ratings of participants’ emotional state from “agony” to “ecstasy.” (Judges unaware of participant’s award status.) • Results: Bronze medallists were rated as happier than the silver medalists. • Why? Automatic Thinking • Most biases/heuristics operate automatically (i.e., without conscious awareness) • Some are highly automatic (e.g., availability), whereas others (e.g., counterfactual thinking) appear to have both automatic and more controlled components Automatic to Controlled Thinking • Automatic thinking: nonconscious, unintentional, involuntary, effortless • Controlled thinking: conscious, intentional, voluntary, effortful Controlled Thinking • Thought suppression: the attempt to avoid thinking about something we would just as soon forget • Have you ever told yourself, “I just won’t think about [dessert, my ex, money…]” • What happens? Example of Thought Suppression & Ironic Processing • Homer Simpson tries to not drink beer. (video clip) Ironic processing & Thought Suppression • Monitoring process (automatic): Search for evidence that unwanted thought is about to pop into consciousness. • Operating process (controlled): Attempt to distract self from detected unwanted thought. • Problem: If under cognitive load (tired, hungry, stressed, under time pressure), operating process breaks down. • Ironic because when we try to STOP thinking about something, it keeps popping into our mind (if we are under cognitive load) How can we be better thinkers? • Given that humans make a lot of errors in reasoning, what can we do to improve our thinking? – TAKE STATISTICS! Nisbett and colleagues found that students who had formal training in statistics (psychology and medicine grad students) performed better on a test of reasoning than grad students in disciplines (chemistry, law) requiring less training in stats (see p. 89 of your text) Conclusions • Schemas and judgmental heuristics help us make sense of the world • They increase our efficiency and speed • They often operate automatically, without conscious awareness • But, they can sometimes lead to serious errors in judgment!