Guidelines for the Use of Pair Programming in a Freshman

advertisement

Guidelines for the Use of Pair

Programming in a Freshman

Programming Class

Jennifer Bevan, Linda Werner, Charlie McDowell

Department of Computer Science

University of California, Santa Cruz

{jbevan,linda,charlie}@soe.ucsc.edu

Problem Statement

Initial exposure to computers and

programming directly affects the retention

of students within the field.

Conventional introductory programming

classes do not prepare students for later

collaborative work.

How do we increase retention and prepare

students for working within a group?

Solution Approach

We used pair programming in the freshman

programming class at UCSC for three

quarters, as part of an NSF research project.

Good early results were achieved, but some

pairs were unstable or ineffective.

The problems encountered by these pairs

were used to create guidelines for future

implementations of pair programming.

Background

Pair programming is one aspect of eXtreme

Programming (XP).

Partners alternate between driving and

observing at (in our case) 1-hour intervals.

All or most individually produced code is

treated as a throwaway prototype.

Reduces ego involvement, typographical

bugs, improvisational design changes.

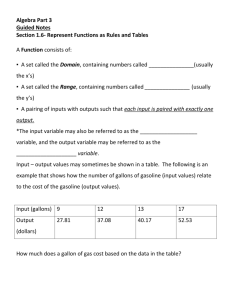

Implementation Details

3 classes, with 3 different instructors, used

pair programming (Fall 00, Winter 01).

1 class, with an instructor who previously

used pair programming, did not (Spring 01).

Each class required 9 programming

assignments (one per week).

2 TAs were assigned for each class.

Implementation Details (cont.)

Paired students were required to submit

individual logs for each assignment:

Time spent driving, observing, and

working alone; confidence in solution;

satisfaction with the experience.

Unpaired students submitted similar logs:

Time spent; confidence in solution;

satisfaction with the experience.

Class-Level Implementation

2 of the paired classes had mandatory

sections, 1 did not.

1 of the paired classes only allowed pairing

within sections, 2 allowed pairing between

sections.

Week n assignments covered similar

material but varied in the expected average

solution time.

Pairing Difficulties

Inability to schedule enough time together.

Unreliability of a partner.

Friction caused by different experience

levels and/or rates of learning.

Lack of understanding or caring about the

pair programming guidelines.

Unwillingness to raise these issues in a

timely fashion.

Scheduling Conflicts

Just under 5% of all pairs had significant

scheduling/reliability problems.

Students’ methods of handling these

problems were hampered by inexperience

with a 10-week term.

Scheduling difficulties were exacerbated

between partners that were not enrolled in

the same section.

Experience Conflicts

Just under 2% of the pairs experienced

friction due to differing experience levels or

rate of learning.

These “higher” level students thought:

Pairing is a waste of their time.

They are not required to be teachers.

Better to just complete the assignment

alone and submit it with both names (!).

Understanding and Buy-In Issues

Some pairs divided and conquered.

Others alternated development by emailing

the latest version back and forth.

Some partners did not want to drive at all.

In most cases, this behavior was discovered,

not reported.

These issues were caused by a lack of

understanding or caring.

Overcoming Pair Problems

Most of these students do not have the

experience or the inclination to quickly

resolve these problems.

Introductory programming courses need to

agressively address these issues.

Classes need to be structured within

constraints of TA and instructor time limits.

Pairing Guidelines 1

Pair Within Enrolled Sections

Reduces scheduling problems by using

enrollment system as conflict resolver.

TAs can facilitate ice-breaking activities

and partner test-drives during first-week

sections.

Pairing Guidelines 2

Pair (somewhat) by skill level

Ask student about willingness to work

with a partner of a higher or lower level.

Unwilling students can be paired with

others at a similar level.

After one successful pairing, willingness

to accept another partner increases.

L. Williams, R. Kessler, W. Cunningham, and R. Jeffries, “Strengthening the

case for pair programming,” IEEE Software, vol. 17, pp. 19-25, July 2000.

Pairing Guidelines 3

Make Sections Mandatory

TA can identify reliability problems faster,

because both partners are expected to be

present.

Students’ grades are linked to meeting with

partner.

A set of acceptable excuses and attendence

requirements add little work for TA or

instructor.

Pairing Guidelines 4

Assign Work as a Function of Section Time

Tailor the problem size such that an

acceptable percentage of the pairs finish

during section.

Does not reduce topic coverage, only

reduces overhead and busywork.

Requires planning by instructor.

Pairing Guidelines 5

Institute a coding standard

Experienced programmers can code to a

standard regardless of opinions on

readability, past familiarity, etc.

Most others have their own “right” style.

Reducing conflicts between styles

reduces conflict between partners.

Pairing Guidelines 6

Create a Pairing-Oriented Culture

Openly discuss common problems inclass or in-section.

Reiterate goals of pair programming.

Added awareness can lead to selfcorrection of problems.

Submission and grading policies need to

support collaborative process.

Why Bother?

“Not that many pairs had problems”

Small target size doesn’t prohibit simple

solutions.

“Their degree is an individual achievement”

The workplace is a collaborative environment.

Any preparation is helpful.

“My students wouldn’t have these problems”

We didn’t think so either.

Conclusions

Many valuable lessons learned from the

variety of pair-programming

implementations during our experiment.

Introductory classes have several common

problems not frequently found in workplace

(or upper division) environments.

Time management, scheduling support,

professional behavior not developed.

Conclusions (cont.)

We developed guidelines for future

implementations that address these

problems.

As more introductory classes adopt pair

programming, these guidelines should be

expanded and adapted.

Paper on impact of pair programming to be

presented at SIGCSE 2002.

Acknowledgements

Dr. Heather Bullock, Dr. Julian Fernald, Wendy R.

Williams, M.S, and Tristan Thomte, from the

Psychology Department at UCSC.

Dr. Alex Pang and Dr. Scott Brandt from the

Computer Science Department at UCSC.

Project funding by the National Science

Foundation (NSF EIA-0089989, “Retaining

women in computer science: Impact of pair

programming”).

Thanks! Any Questions?