6. Quotes and clichés.

advertisement

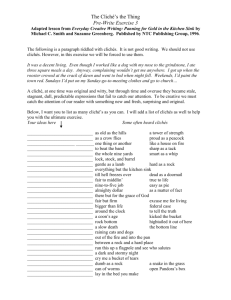

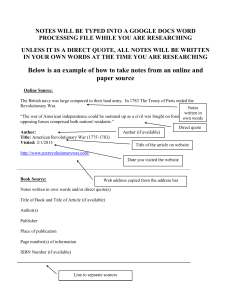

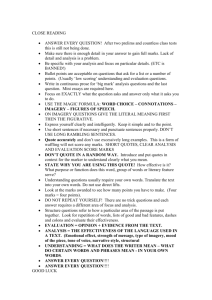

Quotes And clichés The quote Writers for the mass media rely on interviews. These produce quotes. When you refer to what another source has said or written using exact words, it’s a quote. It has quote marks around it. Quote marks Grammar reminder: In the United States quote marks are always outside punctuation, except when using a colon or semicolon. Examples: “Heavy snowfall is forecast for tomorrow,” according to meteorologist Irving Nern. Jenson proposed “an array of solutions to stop high tuition”; the first step is a tax increase. Direct quotes A direct quote uses quote marks (double quotes in the United States) to indicate the exact words a speaker used. Writers or editors are ethically bound to change nothing with quote marks around it. Some editors believe it’s OK to clear up bad grammar in quotes. Direct quotes If a writer or editor prefers to use other words, he or she must remove the quote marks. Example: Nern said, “I plan to run for Congress as long as the people want me.” You can change this, but you need to remove the quotes: Nern said she will consider running for Congress as long as the voters want me. This is called a paraphrase. Partial quotes A writer or editor may use some of the source’s actual words, and some of his or her own. Example: Nern said she will run for Congress “as long as the people will have me.” The first part of that does not use her exact words, so the sentence becomes a partial quote. The paraphrase If a writer or editor prefers to use different words from what the source says, the statement becomes a paraphrase. Example: Nern said if the public support is there, a run for Congress is a possibility. Did she use those words? No, so we can’t put quote marks around them, even if the attribution “said” is there. The paraphrase A paraphrase interprets what a source said. Is the paraphrase accurate? That depends on the writer’s and editor’s judgment. Important note: NEVER add quote marks to paraphrases. You don’t know if those were the exact words. You can remove quote marks if you wish, but consider that mass media stories should have some direct quotes to add interest and color. Attributions Note that attributions (said, says) can be in either the past or present tense, but should be consistent throughout a story. Don’t use clumsy attributions like stated and commented. Long quotes should have attributions in the middle to remind a reader who’s speaking. Example: “I hope to run for governor next year,” said Nern. “If that is successful, I’ll consider a future senate race, and, who knows, maybe president!” Clichés A cliché is a once cute and clever turn of phrase that has become tired and hackneyed through overuse. We try to make our writing fresh and original, so avoid clichés. Levels of clichés We can identify three levels of clichés: Old common phrases. Pop culture phrases. Stereotypes. Old common phrases These are often metaphors. They usually have been around for centuries. Examples: Beehive of activity. Thorn in his side. Chicken with its head cut off. Sometimes these evoke barnyard or nautical experiences long gone from our day-to-day experience. Journalese Trite expressions favored by journalists and business people also are a level of the common cliché. Examples: Acid test. Long-smoldering disagreement. The bottom line. Cautious optimism. Firestorm of criticism. Impact or finalize as a verb. Political clichés Clichés can join with buzzwords to make meaningless quotes. Here’s a classic by John Kerry, secretary of state: “I want to make this crystal clear,” he said. “The president is desirous of trying to see how we can make our best efforts in order to find a way to facilitate.” That’s “crystal clear?” Business clichés Business people use a bevy of clichés. Some of the more extreme examples: “Can we blue sky this synergy later?” “Cascade this to your people and see what the pushback is.” “Run it up the flagpole and see who salutes.” Business clichés In business, apparently, research shows some clichés have a point. It gives others the idea that you get “the big picture” and so might be worthy of promotion to management. Whatever, but in the media these clichés just sound ridiculous. For credibility in media, language should be real. Integrity in writing, as in life, is to say what you mean and mean what you say. Platitudes Also related to this level of cliché are the old and common platitudes that actually are fairly meaningless or inaccurate. A few examples: It’s not rocket science. Good things come to those who wait. Time heals all wounds. If first you don’t succeed, try try again. You’re as young as you feel. Lists of common clichés You can find lists of common clichés and platitudes by internet search. I suggest you become familiar with at least the most common ones so you will be able to identify them when editing. They do take a while to learn, but… Patience is a virtue. Pop culture clichés These are usually fairly new. They become popular based on movies or television shows. Usually pop culture clichés are fads that come and go. Here are a few from 70s and 80s: Sock it to me! (“Laugh In,” 1960s.) Isn’t that special. (“Saturday Night Live,” 1970s.) Sorry about that, chief. (“Get Smart,” 1960s). Stereotypes This third level of cliché is more insidious, and more dangerous. It is based on assumptions by writers and editors who never have experienced a location or culture. Bias or ignorance encourages stereotypes. Stereotypes and journalism It is common for us to compartmentalize groups in society. Perhaps it’s even useful, as we can’t always re-examine our ideas every time we consider a group. So we reduce it to a few broad ideas and move on. But editors in particular need to know that unexamined stereotypes are transmitted and fixed in people’s minds through the media. Common stereotypes Here are some of the most common and damaging stereotypes: African-Americans are lazy drug-dealers. Christians are homophobic. Italians are good lovers. Native Americans are lazy alcoholics. Students are also lazy alcoholics! Fargo is a frozen wasteland. California is a state of crazy liberals. Stereotypical phrases Stereotypes can be shortened into phrases that suggest the cliché: Ghetto-blasting drug dealers; Islamic terrorists; Wild-eyed feminists; Absent-minded college professors; Dumb blonde coeds; Stingy manipulative Jews. Crooked politicians. Uses of stereotypes We do recognize stereotypes in film and novels. They offer a shorthand to help describe a character. Even Shakespeare used them, particularly for Jews and women. Cinderella is an obvious stereotype of women as helpless and vulnerable. This is repeated in typical action movies. In “The Simpsons” Homer portrays the world’s stereotype of Americans: lazy, dumb and fat. Avoiding stereotypes Does a stereotype sometimes have an element of truth? Sometimes. That’s where the stereotype comes from. Nevertheless, editors need to both recognize the damage that stereotypical presumptions in themselves, and in their publications, can do. When you reduce a person to a few simplistic presumptions, you refuse to treat the person with respect as an individual. Do you like to be treated as a “lazy boozing college student?”