Cooperative learning is an approach to organizing classroom

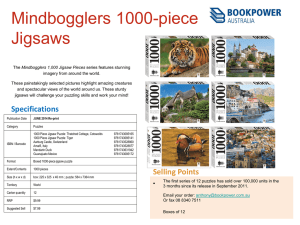

advertisement

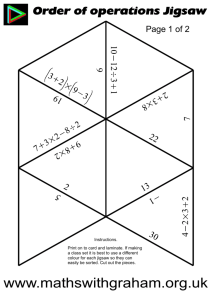

Cooperative learning is an approach to organizing classroom activities into academic and social learning experiences. It differs from group work, and it has been described as "structuring positive interdependence." Students must work in groups to complete tasks collectively toward academic goals. Unlike individual learning, which can be competitive in nature, students learning cooperatively capitalize on one another’s resources and skills (asking one another for information, evaluating one another’s ideas, monitoring one another’s work, etc.). Furthermore, the teacher's role changes from giving information to facilitating students' learning. Everyone succeeds when the group succeeds. Ross and Smyth (1995) describe successful cooperative learning tasks as intellectually demanding, creative, open-ended, and involve higher order thinking tasks. Brown & Ciuffetelli Parker (2009) and Siltala (2010) discuss the 5 basic and essential elements to cooperative learning: 1. Positive interdependence Students must fully participate and put forth effort within their group Each group member has a task/role/responsibility therefore must believe that they are responsible for their learning and that of their group 2. Face-to-Face Promotive Interaction Member promote each other’s success Students explain to one another what they have or are learning and assist one another with understanding and completion of assignments 3. Individual and Group Accountability Each student must demonstrate master of the content being studied Each student is accountable for their learning and work, therefore eliminating “social loafing” 4. Social Skills Social skills that must be taught in order for successful cooperative learning to occur Skills include effective communication, interpersonal and group skills i. Leadership ii. Decision-making iii. Trust-building iv. Communication v. Conflict-management skills 5. Group Processing Every so often groups must assess their effectiveness and decide how it can be improved In order for student achievement to improve considerably, two characteristics must be present a) Students are working towards a group goal or recognition and b) success is reliant on each individual’s learning a. When designing cooperative learning tasks and reward structures, individual responsibility and accountability must be identified. Individuals must know exactly what their responsibilities are and that they are accountable to the group in order to reach their goal. b. Positive Interdependence among students in the task. All group members must be involved in order for the group to complete the task. In order for this to occur each member must have a task that they are responsible for which cannot be completed by any other group member. Think Pair Share Originally developed by Frank T. Lyman (1981), Think-Pair-Share allows for students to contemplate a posed question or problem silently. The student may write down thoughts or simply just brainstorm in his or her head. When prompted, the student pairs up with a peer and discusses his or her idea(s) and then listens to the ideas of his or her partner. Following pair dialogue, the teacher solicits responses from the whole group. Jigsaw Students are members of two groups: home group and expert group. In the heterogenous home group, students are each assigned a different topic. Once a topic has been identified, students leave the home group and group with the other students with their assigned topic. In the new group, students learn the material together before returning to their home group. Once back in their home group, each student is accountable for teaching his or her assigned topic. Jigsaw II Jigsaw II is Robert Slavin's (1980) variation of Jigsaw in which members of the home group are assigned the same material, but focus on separate portions of the material. Each member must become an "expert" on his or her assigned portion and teach the other members of the home group. Reverse Jigsaw This variation was created by Timothy Hedeen (2003) It differs from the original Jigsaw during the teaching portion of the activity. In the Reverse Jigsaw technique, students in the expert groups teach the whole class rather than return to their home groups to teach the content. Reciprocal Teaching Brown & Paliscar (1982) developed reciprocal teaching. It is a cooperative technique that allows for student pairs to participate in a dialogue about text. Partners take turns reading and asking questions of each other, receiving immediate feedback. Such a model allows for students to use important metacognitive techniques such as clarifying, questioning, predicting, and summarizing. It embraces the idea that students can effectively learn from each other. The Williams Students collaborate together to answer a big question that is the learning objective. Each group has differentiated questions that increase in cognitive ability to allow students to progress and meet the learning objective. STAD (or Student-Teams-Achievement Divisions) Students are placed in small groups (or teams). The class in its entirety is presented with a lesson and the students are subsequently tested. Individuals are graded on the team's performance. Although the tests are taken individually, students are encouraged to work together to improve the overall performance of the group. Increased higher level reasoning Increased generation of new ideas and solutions Greater transfer of learning between situations Collaborative learning is a situation in which two or more people learn or attempt to learn something together. Unlike individual learning, people engaged in collaborative learning capitalize on one another’s resources and skills (asking one another for information, evaluating one another’s ideas, monitoring one another’s work, etc.). More specifically, collaborative learning is based on the model that knowledge can be created within a population where members actively interact by sharing experiences and take on asymmetry roles. Collaborative learning is commonly illustrated when groups of students work together to search for understanding, meaning, or solutions or to create an artifact or product of their learning The jigsaw classroom is a cooperative learning technique with a three-decade track record of successfully reducing racial conflict and increasing positive educational outcomes. Just as in a jigsaw puzzle, each piece--each student's part--is essential for the completion and full understanding of the final product. If each student's part is essential, then each student is essential; and that is precisely what makes this strategy so effective. Here is how it works: The students in a history class, for example, are divided into small groups of five or six students each. Suppose their task is to learn about World War II. In one jigsaw group, Sara is responsible for researching Hitler's rise to power in pre-war Germany. Another member of the group, Steven, is assigned to cover concentration camps; Pedro is assigned Britain's role in the war; Melody is to research the contribution of the Soviet Union; Tyrone will handle Japan's entry into the war; Clara will read about the development of the atom bomb. Eventually each student will come back to her or his jigsaw group and will try to present a well-organized report to the group. The situation is specifically structured so that the only access any member has to the other five assignments is by listening closely to the report of the person reciting. Thus, if Tyrone doesn't like Pedro, or if he thinks Sara is a nerd and tunes her out or makes fun of her, he cannot possibly do well on the test that follows. To increase the chances that each report will be accurate, the students doing the research do not immediately take it back to their jigsaw group. Instead, they meet first with students who have the identical assignment (one from each jigsaw group). For example, students assigned to the atom bomb topic meet as a team of specialists, gathering information, becoming experts on their topic, and rehearsing their presentations. We call this the "expert" group. It is particularly useful for students who might have initial difficulty learning or organizing their part of the assignment, for it allows them to hear and rehearse with other "experts." Once each presenter is up to speed, the jigsaw groups reconvene in their initial heterogeneous configuration. The atom bomb expert in each group teaches the other group members about the development of the atom bomb. Each student in each group educates the whole group about her or his specialty. Students are then tested on what they have learned about World War II from their fellow group member. What is the benefit of the jigsaw classroom? First and foremost, it is a remarkably efficient way to learn the material. But even more important, the jigsaw process encourages listening, engagement, and empathy by giving each member of the group an essential part to play in the academic activity. Group members must work together as a team to accomplish a common goal; each person depends on all the others. No student can succeed completely unless everyone works well together as a team. This "cooperation by design" facilitates interaction among all students in the class, leading them to value each other as contributors to their common task. The jigsaw classrom is very simple to use. If you're a teacher, just follow these steps: 1. Divide students into 5- or 6-person jigsaw groups. The groups should be diverse in terms of gender, ethnicity, race, and ability. 2. Appoint one student from each group as the leader. Initially, this person should be the most mature student in the group. 3. Divide the day's lesson into 5-6 segments. For example, if you want history students to learn about Eleanor Roosevelt, you might divide a short biography of her into stand-alone segments on: (1) Her childhood, (2) Her family life with Franklin and their children, (3) Her life after Franklin contracted polio, (4) Her work in the White House as First Lady, and (5) Her life and work after Franklin's death. 4. Assign each student to learn one segment, making sure students have direct access only to their own segment. 5. Give students time to read over their segment at least twice and become familiar with it. There is no need for them to memorize it. 6. Form temporary "expert groups" by having one student from each jigsaw group join other students assigned to the same segment. Give students in these expert groups time to discuss the main points of their segment and to rehearse the presentations they will make to their jigsaw group. 7. Bring the students back into their jigsaw groups. 8. Ask each student to present her or his segment to the group. Encourage others in the group to ask questions for clarification. 9. Float from group to group, observing the process. If any group is having trouble (e.g., a member is dominating or disruptive), make an appropriate intervention. Eventually, it's best for the group leader to handle this task. Leaders can be trained by whispering an instruction on how to intervene, until the leader gets the hang of it. 10. At the end of the session, give a quiz on the material so that students quickly come to realize that these sessions are not just fun and games but really count. The Problem of the Dominant Student Many jigsaw teachers find it useful to appoint one of the students to be the discussion leader for each session, on a rotating basis. It is the leader's job to call on students in a fair manner and try to spread participation evenly. In addition, students quickly realize that the group runs more effectively if each student is allowed to present her or his material before question and comments are taken. Thus, the selfinterest of the group eventually reduces the problem of dominance. The Problem of the Slow Student Teachers must make sure that students with poor study skills do not present an inferior report to the jigsaw group. If this were to happen, the jigsaw experience might backfire (the situation would be akin to the untalented baseball player dropping a routine fly ball with the bases loaded, earning the wrath of teammates). To deal with this problem, the jigsaw technique relies on "expert" groups. Before presenting a report to their jigsaw groups, each student enters an expert group consisting of other students who have prepared a report on the same topic. In the expert group, students have a chance to discuss their report and modify it based on the suggestions of other members of their expert group. This system works very well. In the early stages, teachers may want to monitor the expert groups carefully, just to make sure that each student ends with an accurate report to bring to her or his jigsaw group. Most teachers find that once the expert groups get the hang of it, close monitoring becomes unnecessary. The Problem of Bright Students Becoming Bored Boredom can be a problem in any classroom, regardless of the learning technique being used. Research suggests, however, that there is less boredom in jigsaw classrooms than in traditional classrooms. Youngsters in jigsaw classes report liking school better, and this is true for the bright students as well as the slower students. After all, being in the position of a teacher can be an exciting change of pace for all students. If bright students are encouraged to develop the mind set of "teacher," the learning experience can be transformed from a boring task into an exciting challenge. Not only does such a challenge produce psychological benefits, but the learning is frequently more thorough. The Problem of Students Who Have Been Trained to Compete Research suggests that jigsaw has its strongest effect if introduced in elementary school. When children have been exposed to jigsaw in their early years, little more than a "booster shot" (one hour per day) of jigsaw in middle school and high school is required to maintain the benefits of cooperative learning. But what if jigsaw has not been used in elementary school? Admittedly, it is an uphill battle to introduce cooperative learning to 16-year olds who have never before experienced it. Old habits are not easy to break. But they can be broken, and it is never too late to begin. Experience has shown that although it generally takes a bit longer, most high school students participating in jigsaw for the first time display a remarkable ability to benefit from the cooperative structure. In Conclusion Some teachers may feel that they have already tried a cooperative learning approach because they have occasionally placed their students in small groups, instructing them to cooperate. Yet cooperative learning requires more than seating youngsters around a table and telling them to share, work together, and be nice to one another. Such loose, unstructured situations do not contain the crucial elements and safeguards that make the jigsaw and other structured cooperative strategies work so well. Placemat and Round Robin This activity is designed to allow for each individual’s thinking, perspective and voice to be heard, recognised and explored. 1. 2. 3. Form participants into groups of four. Allocate one piece of A3 or butcher’s paper to each group. Ask each group to draw the diagram on the paper. 4. 5. 6. The outer spaces are for each participant to write their thoughts about the topic. Conduct a Round Robin so that each participant can share their views. The circle in the middle of the paper is to note down (by the nominated scribe) the common points made by each participant. Each group then reports the common points to the whole group. 7. What is Cooperative Learning? Cooperative learning involves more than students working together on a lab or field project. It requires teachers to structure cooperative interdependence among the students. These structures involve five key elements which can be implemented in a variety of ways. There are also different types of cooperative groups appropriate for different situations. More than Just Working in Groups Five key elements differentiate cooperative learning from simply putting students into groups to learn (Johnson et al., 2006). 1. Positive Interdependence: You'll know when you've succeeded in structuring positive interdependence when students perceive that they "sink or swim together." This can be achieved through mutual goals, division of labor, dividing materials, roles, and by making part of each student's grade dependent on the performance of the rest of the group. Group members must believe that each person's efforts benefit not only him- or herself, but all group members as well. 2. Individual Accountability: The essence of individual accountability in cooperative learning is "students learn together, but perform alone." This ensures that no one can "hitch-hike" on the work of others. A lesson's goals must be clear enough that students are able to measure whether (a) the group is successful in achieving them, and (b) individual members are successful in achieving them as well. 3. Face-to-Face (Promotive) Interaction: Important cognitive activities and interpersonal dynamics only occur when students promote each other's learning. This includes oral explanations of how to solve problems, discussing the nature of the concepts being learned, and connecting present learning with past knowledge. It is through face-to-face, promotive interaction that members become personally committed to each other as well as to their mutual goals. 4. Interpersonal and Small Group Social Skills: In cooperative learning groups, students learn academic subject matter (taskwork) and also interpersonal and small group skills (teamwork). Thus, a group must know how to provide effective leadership, decisionmaking, trust-building, communication, and conflict management. Given the complexity of these skills, teachers can encourage much higher performance by teaching cooperative skill components within cooperative lessons. As students develop these skills, later group projects will probably run more smoothly and efficiently than early ones. 5. Group Processing: After completing their task, students must be given time and procedures for analyzing how well their learning groups are functioning and how well social skills are being employed. Group processing involves both taskwork and teamwork, with an eye to improving it on the next project. Similarly, Kagan (2003) has developed the easily recalled acronym PIES to denote the key elements of positive interdependence, individual accountability, equal participation, and simultaneous interaction where the latter 2 components encompass the final three described above. Implementing the Elements of Cooperative Learning There are a variety of techniques that can be used to promote one or more of the elements of effective cooperative learning groups. The list below is intended to be representative rather than exhaustive. Positive Interdependence: o Big Project: This is the usual motivation for assigning students to work in groups in the first place, a learning task that a student cannot accomplish alone in a reasonable length of time. Often these projects are more interesting and can teach more than simplified versions. See examples of projects. o Jigsaw: Divide the group into specialists on particular areas of the material to be learned. Specialists in one area work together to develop expertise in their specialty, then return to their original group to combine their new expertise with those of experts on other aspects of the material to finish the project. For a complete description of this technique, see the jigsaw module. o Peer Review: Providing students with the opportunity to learn how to provide and received constructive feedback is an important part of process of conducting research. The peer review module describes how to use student pairs or groups to help each other with written work. o Ways to promote positive interdependence include (Smith and Waller 1997, p. 202): Output goal interdependence- a single product is produced by the group Learning goal interdependence- the group ensures that every member can explain the group's product Resource interdependence- members are provided parts of the assignment or relevant information or the group is only provided one copy of the assignment Role interdependence- members are given distinct roles that are key to the functioning of the group Individual Accountability: o Individual Grades: Individuals can be given quizzes and exams. Likewise, parts of group projects can be done independently or randomly drawn students can provide oral/written reports on group results. o Within-Group Peer Assessment: Another way to discourage students from letting others do their share of group work is to have students (anonymously) rate their group mates and include the average rating from all of a student's group mates as part of his or her grade. o See the assessment of cooperative learning page for more information about how to encourage individual accountability. Face-to-Face (Promotive) Interaction: o Student Roles: Encourage students to interface with multiple parts of the project by assigning roles that require interaction with the rest of the group as they work, such as checking data, keeping the group on task, or keeping records. o Online Bulletin Boards: If students have limited time to meet face-toface (common on commuter campuses and online courses), the instructor can set up an online asynchronous bulletin board for students to post what is essentially an e-mail to the group. Many forms of classroom management software such as WebCT and Blackboard make this possible. It also allows the instructor to monitor interaction. Interpersonal Skills: o Discussion: It may be helpful to explain to your students why they are working together and how the group can promote their learning. o Practice: Give students time to learn to work together before expecting spectacular results from cooperative learning. If you assign students to groups early in the term and let them do a series of projects together, not only will they learn each other's schedules and particular strengths, they will learn to ask and answer better questions of each other about their projects and progress. Group Processing: o Reflections: It may be worthwhile for group members to write individual, private reflections on their learning after the project, citing which parts of the project and which group members contributed to various discoveries, then bring the group back together to discuss the project. Fink (2003) describes this process of 'learning how to learn' as one of five key components that contribute to significant learning experiences as it enables students to become better students, inquire about a subject and construct knowledge and become "self-directing learners." Definition: Cooperative learning is a method of instruction that has students working together in groups, usually with the goal of completing a specific task. This method can help students develop leadership skills and the ability to work with others as a team. Cooperative Learning Definition: Cooperative learning is a successful teaching strategy in which small teams, each with students of different levels of ability, use a variety of learning activities to improve their understanding of a subject. Each member of a team is responsible not Collaborative Learning Definition: "Collaborative learning is based on the idea that learning is a naturally social act in which the participants talk among themselves (Gerlach, 1994). It is through the talk that learning occurs." only for learning what is taught but also for helping teammates learn, thus creating an atmosphere of achievement. (U.S. Dept. of Ed. Office of Research, 1992) each person is responsible for a portion of the work participants work together to solve a problem many times the teacher already knows the problem and solution students will be working towards many times teacher does not have a pre-set notion of the problem or solution that students will be researching