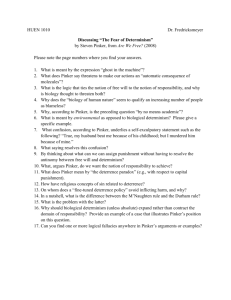

Pinker Pre-Reading Questions/Moral Dilemmas

advertisement