Cohen_PartingWays - Digital Access to Scholarship at Harvard

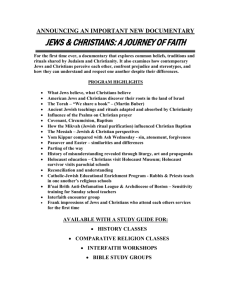

advertisement