H 2

WYKŁAD III & IV

Magazynowanie wodoru. Kataliza niskotemperaturowego wydzielania wodoru.

A. Dlaczego wodór?

B. Trochę historii.

C. Stan obecny zagadnienia.

D. Przyszłość.

E.

Najważniejsze problemy i wyzwania. Zalety magazynowania w fazie stałej.

F.

Jak może pomóc teoria?

(i) Właściwości fizyczne i chemiczne wodoru.

(ii) Kontrola temperatury rozkładu wodorków binarnych. Przewidywania modelu.

(iii) Rozszerzenie na wodorki ternarne.

(iv) Kataliza heterogeniczna; synteza mechanochemiczna i klasyczna.

G. Dowiedz się więcej.

THE DREAM

“I believe that one day hydrogen and oxygen, which together form water, will be used either alone or together as an inexhaustible source of heat and light”

(Jules Verne, The mysterious island , 1874)

Why hydrogen?

Combustion of fossil fuels & other:

Coal

Petrol /mineral oil/

gas(oline)

Methane /natural gas/

Recycled tires, etc.

Renewable energies:

Solar energy

Wind energy

Geothermal energy

Hydroenergy

Nuclear energy:

Nuclear reactor

-

“Cold fusion”

Greenhouse gas (CO

2

)

Other pollutants (SO x

, NO x

Big politics etc.)

Oil plots, oil wars, etc.

Limited amount

Limited geopolitics

Landscape preservation issues

Radioactive pollutants

“Atomic bomb” risk

Pros and Cons

- Hydrogen is the lightest of the elements with an atomic weight of 1.

- Liquid hydrogen has a very small density of 0.07.

- The advantage is that H stores approximately 2.6 times the energy per unit mass as gasoline.

- The disadvantage is that it needs about 4 times the volume for a given amount of energy. a 15 gallon automobile gasoline tank contains 90 pounds of gasoline; the corresponding H tank would be 60 gallons, of weight of only 34 pounds

When hydrogen is burned in air the main product is water (some nitrogen compounds may also be produced and may have to be controlled

- Should greenhouse warming turn out to be an important problem, the key advantage of hydrogen is that carbon dioxide is not produced when hydrogen is burned.

Why storage in the solid state?

Other ways:

- physisorption (glass, sponges etc.)

- liquid (price, volume, T<250 K tanks)

L. Schlapbach, A. Züttel,

Nature 414 , 353 (2001).

- compression (price, volume, permeability of containers, pressure now up to 800 bar)

1937

Gaseous & liquid fuels vs solid fuels

1986

2001

?

1999

USA C

51.0

ENERGY nuclear, hydroelectric, wind, solar, biomass, geothermal

CH

2.25

CH

4 other

3.2

15.2

30.0

CO

2

EMISSION 79.6

OUTPUT

RATE

/pounds

CO

2 per

1 kWh

2.12

1.92

1.31

4.7

15.0

0.00

1998

USA

C

TOTAL CO

2

EMISSION

36.4

CH

2.25

41.7

other

CH

4

20.8

DIRTY AND CLEAN ENERGY

31.3

15.9

23.8

16.0

13.0

CONTRIB. TO THE TOTAL

ENERGY GENERATION

C 68%

H 32%

Hubbert’s Law

GLOBAL ENERGY CRISIS

AROUND 2010…2050

$$$ Value

Based on statistical data, and on prognosis of LH price,

H is to take 5% of global oil market in 2010

Global oil market is $ 700 bln/year

H is to take $ 35 bln/year

Tanks with MHS are thought to take $ 5 bln/year

Invention may be sold or licensed for

$ 1 bln/year

USA

Freedom /$ 150 mln incl.

$ 40 mln government share/

EUROPE

Fuchsia, Hystory,

Hymosses /$ 10 mln/

(fuel cells $ 340 mln!)

JAPAN

Protium /$ ??? mln/

WE-NET /$ 4 mln p.a./

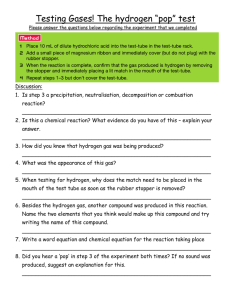

Some history

16th century – F. B. Paracelsus (Swiss…) first described an air which bursts forth like the wind

1671 – Robert Boyle published a paper in which he described the reaction between iron filings and dilute acids which results in the evolution of gas

1766 – Henry Cavendish discovers “inflammable gas from metals”

(Lavoisier gives the name for it in 1783)

1783 – J. A. C. Charles suggests using hydrogen in balloons

Nov.25, 1793 – the first balloon is sent up from

British soil

1807 – Dalton’s theory of atoms is published; was the symbol used for hydrogen

May 6, 1937 – the Hindenburg tragedy

Jan. 28, 1986 – the Challenger space shuttle catastrophe

1980’s – numerous explosions in the diborane factories

1839 – William Robert Grove invents fuel cell

1960 ’s – NASA searches for energy supplies for the spacecraft

1998

–2000 Ballard Power Systems introduces 205 kW fuel cells being used in six buses in the U.S. (Chicago) and Canada (Vancouver)

May 1999 – the first public liquid–hydrogen filling station has been opened in at Munich Airport

Feb. 2001 – Eur. Comm. funds the FUCHSIA Project

Feb. 2001 – a six-month tour of a fleet of ten BMW

750hL liquid hydrogen powered sedans around the globe starts in oil–producing Dubai (UAE)

Aug. 2001 – the first solar-powered hydrogen production and fueling station in the Los Angeles area opened by

American Honda Motor Co.

2003 – Toyota Motor Co. is poised to be the first to offer a pure-hydrogen fuel cell vehicle to a limited public

2010/2020 – mass production of the fuel cell-powered vehicles is expected

CLEAN HYDROGEN ECONOMY FOR THE FUTURE

•

CH

4

+ 2 H

2

O

CO

2

+ 4 H

2

•

C–H bond activation

Hydrogen production

H

2

(gas)

• photoelectrochemical generation

(electrolysis of water), green energy

Hydrogen storage

• high–pressure cryogenic tanks chemical reactions

H

2

(compressed) H

2

(liquid) H (solid chemicals)

Hydrogen combustion

(Hybrid) engine H

2

/O

2

Fuel cell

Zero–emission vehicle

Effects for the planet of the increased water circulation = ???

Budowa Ogniwa Paliwowego (Fuel Cell).

ANODA /Pt Nafion® KATODA /Pt

Energia chemiczna

Energia elektryczna małe straty cieplne, duża wydajność w por. z cyklem Carnota

Rodzaje ogniw paliwowych H

2

/O

2

:

Alkaliczne (150–200 o C) – wymagają użycia bardzo czystego H

2 i O

2

Na kwas fosforowy (150–200 o C) – głównie średnie do dużych aplikacji stacjonarnych

Na stały tlenek (1000 o C) – ogniwa ekstremalnie wysokotemperaturowe, tolerują względnie zanieczyszczone paliwa wodorowe

Z membraną wymieniającą proton (Proton Exchange Membrane) lub polimerowo–elektrolitową (Polymer Electyrolyte) Fuel Cell (60–100 o C) – najbardziej rozwinięty rodzaj ogniw, największa ilość energii na jednostkę objętości ogniwa, najprawdopodobniej jedyny kandydat do zasilania środków transportu przyszłości

Na stopiony węglan (650 o C) – ogniwa wysokotemperaturowe, mogące używać bezpośrednio paliwa kopalnego, lub nawet CO

Protonowo–ceramiczne (700 o C) – używa bezpośrednio paliw kopalnych

Bezpośrednie ogniwa metanolowe (50–100 o C) – przyszłość w małych zastosowaniach moblinych

Zn/powietrze

– niski koszt, względna nieodwracalność, użycie w armii

Stacjonarne FC

Transport/bus FC

Przenosne FC Cell.Ph. FC

Laptop FC

Anchorage /Alaska/

• Yesterday:

• Today:

• Tomorrow:

Car of the future: BMW 750 hL presented during EURO 2000

BMW 750 hL (München 2000)

6 fuel-cell busses (Chicago & Vancouver 1999-2001) the first commercial Honda & Toyota (Japan & California 2002/3) cheap fuel cells, cheaper H

2

(US & Canada 2010)

Who does not pick up this subject NOW, most probably would not have chance to work on it at all.

COMMANDEMENTS OF HYDROGEN STORAGE

(i) High storage capacity : minimum 6.5 wt % abundance of hydrogen and at least 65 g/l of hydrogen available from the material;

(ii) T dec

= 60–120 o C ;

(iii) Reversibility of the thermal absorption / desorption cycle: low temperature of hydrogen desorption and low pressure of hydrogen absorption (a plateau pressure of the order of few bars at room temperature), or an ease of nonthermal transformation between substrates and products of decomposition;

(iv) Low cost ;

(v) A nontoxic, nonexplosive , inert etc., storage medium.

EXAMPLES OF CHEMICAL HYDROGEN STORES

1. PdH

0.6

: 0.6 wt%, excellent reversibility, $ 1000/oz, >$1mln/1kg H

2. NaH: 4.2 wt%, good reversibility, T dec

> 425 o C

3. NaAlH

4

& TiO

2

: 5.5 wt%, T dec

> 125 o C, reversibility OK

4. MgH

2

: 7.6 wt%, T dec

> 330 o C, poor reversibility

5. “Li

3

Be

2

H

7

“: 8.7 wt %, T dec

> 300 o C, toxicity, cost

6. NaBH

4

/H

2

O

(l)

: 9.2 wt%, expensive Ru catalyst, no reversibility

7. AlH

3

: 10.0 wt %, very cheap Al, T dec

> 150 o C, no reversibility

8. H

2

O

(l)

: 11.1 wt%, liquid, thermal decomposition difficult

9. MeOH

(l)

: 12.5 wt%, toxic liquid, activation difficult

10. LiH: 12.6 wt%, T dec

> 700 o C

11. NH

3(l)

: 17.6 wt%, large N – H bond activation barrier

11. BeH

2

: 18.2 wt%, extremely toxic, T dec

> 250 o C, no reversibility

12. CH

4

: 25.0 wt%, gas, thermal activation very difficult

13. Carbon nanotubes: ??? Wt%, ???

Compare to Mg

2

NiH

4

: 3.6 wt% (ii, iii, iv, v)

(ii,iii, v)

(iii, iv, v)

(ii, iii, iv, v)

(i, iv, v)

(i, iii)

(i, ii, iv, v)

(i, iv, v)

(i, iii, iv, v)

(i, iv)

(i, iv, v)

(i, iv)

(i)

(i, iv)

(i, ii, iii, v?)

80

60

40

20

0

0

160

140

120

100

5 10 15 gravimetric H content [wt%]

20 25

MAIN CHEMICAL PLAYGROUND

Problems with setting of the position of H in the periodic table of chemical elements

H as H + :

• H’s I

P is similar to that for Cl.

• “Dimension” of proton is very different depending on the solvating agent; spectrum of energies of

H bond is very broad.

H as H 0 .

• It is a gaseous nonmetal. Has never been metallized in the solid state.

• H radical has enormous tendency for pairing.

Bonding energy is 436 kJ/mole, and it is slightly smaller than those of O

2

P

2

.

or

H as H

–

:

• Creates metal hydrides (H as hydride anion) much easier than other Group 1 elements.

• Dimension of H

– is very susceptible to the polarization properties of the metal, and most often it is in between of those for Cl

– and F

–

.

Difference of properties for three available oxidation states of H is the largest among all chemical elements at their typical oxidation states

(derivative of energy upon charge is large).

H

2

EVOLUTION REACTION PATHWAY

Reaction path for evolving H

2 from a H–containing material. Elongation of the M–H bonds occur along R

M–H coordinate, and the pairing of two H atoms in a H

2 molecule proceeds along the R

H–H coordinate. The actual reaction coordinate is a combination of these two.

E /eV

+13.60

0.0

-

0.75

+1

WHICH REDOX EQUILIBRIUM TO PLAY?

H

-

I /H

2 or H +1 /H

2

I

P

/kJ mol

–1

E

A

/kJ mol

–1

I

P

/kJ mol

–1

E

A

/kJ mol

–1

H

1312

Li

520.2

H

72.8

Li

59.6

H

1312

F

1681

H

72.8

F

328

Na

495.8

K

418.8

Rb

403.0

Cs

375.7

Na

52.8

K

48.4

Rb

46.9

Cs

45.5

Cl

1251.2

Br

1139.9

I

1008.4

At

920

Cl

349

Br

324.6

I

295.2

At

270.1 n

0

-

1

H +

H 0

H

–

Fig.2. The dependence of the electronic energy of the H n

species on the oxidation state of hydrogen, n. The hardness (the derivative of energy on the electron density) is schematically shown as dotted lines. Note that the hardness of H n

species strongly decreases in the direction:

H

I+

> H

0

> H

I–

.

ATTEMPTS OF H METALLIZATION

1

1 1

H

2 3

Li

3 11

Na

4 19

K

5 37

Rb

6 55

Cs

7 87

Fr

2

Sr

56

Ba

88

Ra

4

Be

12

Mg

20

Ca

38

3

21

Sc

39

Y

71

Lu

103

Lr

57

La

89

Ac

4

22

Ti

40

Zr

72

Hf

Rf

58

Ce

90

Th

Db

59

Pr

91

Pa

5

23

V

41

Nb

73

Ta

6

24

Cr

42

Mo

74

W

Sg

7

N

3

Li

5

B

85

At

1

H

7

25

Mn

43

Tc

75

Re

Bh

8

60

Nd

92

U

61

Pm

93

Np

Niemetal

62

Sm

94

Pu

Metal

26

Fe

44

Ru

76

Os

108

Hs

9

27

Co

45

Rh

77

Ir

109

Mt

63

Eu

95

Am

10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18

2

5 6 7 8

H

9

He

10

28

Ni

46

Pd

78

Pt

110

Uun

29

Cu

47

Ag

79

Au

111

Uuu

30

Zn

48

Cd

80

Hg

112

Uub

B

13

Al

31

Ga

49

In

81

Tl

113

Uut

C

14

Si

32

Ge

50

Sn

82

Pb

114

Uuq

N

15

P

33

As

51

Sb

83

Bi

115

Uup

O

16

S

34

Se

52

Te

84

Po

116

Uuh

F

17

Cl

35

Br

53

I

85

At

117

Uus

64

Gd

96

Cm

65

Tb

97

Bk

Zmetalizowany tylko w fazie ciekłej

66

Dy

98

Cf

Niemetal zmetalizowany pod wysokim p

67

Ho

99

Es

Brak prób, teoretycznie w zasięgu metalizacji

68

Er

100

Fm

69

Tm

101

Md

70

Yb

102

Nb

Ne

18

Ar

36

Kr

54

Xe

86

Rn

118

Uuo

Which species are to be involved in the charging/recharging process of the Hydrogene Storage Material?

H

–1

H +1 + e

H

-

0

+ e

-

H 0

2 H 0

H

H +1 + H

-

1

2

H

2

(

H 0 = +0.75 eV)

(

H 0 = –13.60 eV)

(

H 0 = –4.52 eV)

(

H 0 = –17.37 eV)

(1a)

(1b)

(1c)

(1d)

•

It should be easy to play the H

-

I /H

2 equilibrium;

•

It is much more difficult to play the H +1 /H

2 one;

•

It is quite difficult to play the 2H 0 /H

2 equilibrium;

• It is the most difficult to play the (H +1 ,H

–1

)/H

2 one.

Standard enthalpies of formation

H f

0

[kJ/mol] of binary hydrides of the main group elements.

MH

Li

-116.3

Na

-56.5

K

-57.7

Rb

-52.3

Cs

-54.2

MH

Be

Mg

Ca

Sr

Ba

2

-18.9

-75.2

-181.5

-180.3

-177.0

MH

3

B

[1]

+36.4

Al

-46.0

+92

[1,2]

Ga

???

[3]

+118

[1,2]

In

???

[3]

+175

[1,2]

Tl

#

???

[3]

+245

[1,2]

MH

C

4

-74.6

Si

+34.3

Ge

+90.8

Sn

+162.8

Pb

+181.1

[2]

+251.5

[4]

MH

N

-45.9

P

+5.4

As

Sb

Bi

+230.6

3

+66.4

+145.1

[4]

MH

O

2

-285.8

S

-20.6

Se

+29.7

Te

+99.6

Po

+188.6

[4]

MH

F

-273.3

Cl

-92.3

Br

-30.3

I

+26.5

At

+104.8

[4]

[1]

[2]

Molecular dimer, M

2

Theoretical value.

H

6

.

[3]

Value for solid hydride is not known. This hydride certainly decomposes below 0 o

C, and a

H

(standard conditions) cannot be measured.

[4]

Extrapolated from experimental values.

f

0

value

Chemical rationale behind the metal/hydrogen avoided crossing curve.

Size, electric charge, orbital energy, hardness, and standard redox potential.

molecule R

0

/Å q(H)/e HOMO/eV

M n+ + n H

-

1

M + n/2 H

2 atom R cat

/Å E 0 /V T dec

/ o C

Electronegativity vs the total charge & substituents

B 0 > B Ga + > Ga 0 > Ga

–

Zn +2 > Zn

–2

[BH

3

+40 o

]

2

< LiBH

C, +275 o

4

C

[GaH

2

][BH

4

] < [GaH

3

]

2

< LiGaH

4

–35 o C, –15 o C, 50 o C

[AlH

3

] < Li[Al

2

H

7

–

] < LiAlH

4

150 o C, 160 o C, 165

[InH

3

???

] < InH

, –30 o C

4

–

MgH

2

[ZnH

2

+90

< Sr

2

[MgH o

] < K

2

[ZnH

C, +407 o C

4

]

6

] < Ba

2

[MgH

327, 377, > 427 o C

6

]

[GaH][BH

4

]

2

< [GaH

2

][BH

4

] < [GaH

3

]

2

< LiGaH

4

–73 o C, –35 o C, –15 o C, +50 o C

Na

2

[BeH

4

] > [BeH

2

] > Be[BH

4

]

2

+380 o C, +250 o C, +25 o C

Ga +3 > GaCl 2+ > GaCl

2

1+

[GaH

3

]

2

< [GaClH

2

]

2

< [GaCl

2

H]

2

–15 o C, –15 o C, +50 o C

Zn +2 > ZnI 1+

[ZnH

2

] < [ZnHI]

+90 o C, +110 o C

[Bi 5+ ] > [BiCl

4

1+ ] unknown, [BiCl

4

1+ ][H 1– ] known as

H 1+ Bi III Cl

4

As +5 > AsPh

4

1+

[AsH

5

] < [AsPh

4

H]

???

, obtained

M

2

Na, & Sr

2

M

2

Pd 0 H

2

M=Li,

Pd II H

4

M=K,

Rb, Cs (1.625–

1.64 Å )

M

2

Pt II H

4

K, Rb, Cs

M=Na,

(MH)

2

Pt II H

4

M=Sr, Ba

M

2

Pt IV H

6

M=K,

Rb, Cs

Pd 0 H

4

(1.674–1.676 Å) d d d

10

8

6

= Au

= Au

= Au

1+

3+

5+

[AuCl

[AuCl

[AuF

6

–

2

–

4

–

]

]

]

800

700

600

Li +

Ba 2+ , Sr 2+

Ca 2+

500

Na +

400

Er 3+

300

Mg 2+

Y 3+

Be 2+ , Pu 3+

200

U 3+

Al 3+

100

0

V 2+

Ga

Zn 2+

B 3+

P 3+

3+ Cd 2+

Sn 4+

Sb 3+

-100

H

2

/2H

-

H 0

·

/H

-

Hg 2+

-200

-3.5

-2.5

-1.5

-0.5

0.5

1.5

E

0

/ V

BaRuH

9

Cs

3

RuH

10

RuH

7

& vs

Mg

2

FeH

6

FeH

2 vs

M

2

PtH

6

PtH

4

… vs

[M III H

4

1– ],

M=Cr, Eu, Yb

[CdH

????????

[HgH

[PtH

6

]

4

2–

4

2–

]

]

Predictions of the T dec vs E

0 relationship for binary hydrides

Hydride Redox pair E

0

/V T dec

/ o

C Hydride Redox pair E

0

/V T dec

/ o

C

ScH

ZrH

PaH

[1]

3

[1,3]

ThH

HfH

4

4

[1]

4

[1]

4

[5]

YbH

TaH

UH

TiH

3

[2]

5

[1]

4

3

[1]

Sc

Th

IV

Hf

Zr

Pa

III

IV

IV

IV

/Sc

0

/Th

/Hf

/Zr

0

/Pa

0

0

III

EuH

InH

PH

5

3

[1]

[1]

3

[2]

VH

WH

4

3

[1]

H

Eu

In

III

III

3

PO

V

4

III

/H

/V

WO

2

/Eu

/In

3

II

/W

0

II

PO

3

0

PaH

5

PaO(OH)

2

+

/Pa

-

0.35 15

-

0.338 15

-

0.276 11

IV

-

0.255 10 MoH

-

0.119 1

-

0.1 0

AsH

5

H

3

TeH

4

AsO

Te

4

IV

/HAsO

2

+0.560 -68

/Te

0

+0.57 -69

SbH

NpH

6

5

[1]

AtH

5

Sb

H

2

2

O

5

NpO

2

/SbO

+

+0.605 -75

MoO

+

4

/MoO

/Np

IV

HAtO/At

0

2

+0.646 -82

+0.66

+0.7

-84

-91

NbH

5

[2]

Yb

Ta

U

Ti

Nb

2

III

V

/Yb

/Ta

IV

/U

III

III

/Ti

O

5

0

II

/Nb

II

II

-

2.03 239 WH

-

1.83 185 TiH

-

1.70 156 SH

-

1.55 127

-

1.46 113 UH

6

[1,2]

[1]

6

4

[4]

WO

NpH

6

4

[1]

TiO

HSO

Np

UO

3

4

IV

/W

-

2

/H

/Np

2

2+

/Ti

2

2

O

III

SO

III

/U

IV

5

-

0.029

3

+0.1

-5

+0.16 -21

+0.18

+0.27

-15

-22

-31

-

1.05

-

0.81

-0.52

-

0.37

-

0.1

63

43

25

16

0

BiH

TlH

3

3

PoH

2

[1]

UH

SH

5

4

[4]

Bi

Po

UO

H

2

Tl

III

II

2

III

+

/Bi

0

/Po

/U

SO

3

/Tl

0

0

IV

/S

0

+0.317

+0.37

+0.38

+0.50

+0.72

-36

[6]

-42

-44

-59

-95

[1]

Species isolated in the noble gas matrixes.

[2]

Organophosphine–stabilized hydrides have been obtained.

[3]

Mixed–valence hydrides exist (Th

4

H

15

, Yb

3

H

8

, Eu

[4]

Theoretical predictions of kinetic stability exist.

3

H

7

).

[5]

Mentioned as a reactant in one study.

[6]

Recently isolated at –55 o

C; fast decomposes at –40 o

C .

T dec

= –31.396 x 3 – 41.078 x

– 75.231 x – 7.3957

2

R 2 = 0.9777

T dec vs

H dec for some binary and ternary hydrides

350

R

2

= 0.974

300

250

200 binary Group 13 hydrides ternary Al hydrides predictions of

E0 for In, Tl

150

-150

100

50

0

-50

-50

50

-100

-150 delta H dec

R

2

= 0.996

150

Energy

D)

MH x

Aspects of catalysis in hydrogen storage

A)

Reaction path for H

2 evolving from different MHS.

M + x/2 H

2

C)

B)

A) Thermodyn. unstable MHS with low activation barrier and low T dec

; stores H irreversibly;

B) Thermodyn. stable MHS with high activation barrier and high T dec

; stores H reversibly;

C) Thermodyn.

slightly stable

MHS with intermediate

T dec

; stores H irreversibly;

D) target : catalytically– enhanced thermodyn.

slightly stable MHS with low T dec

; stores hydrogen reversibly.

Vertical arrows symbolize activation barrier for the decomposition process.

Reaction coordinate

Experimental pathway

Hydrogen Store Catalyst

Mechanochemical synthesis

(high-energy ball-milling)

Target: doped MHS

Wet (classical) synthesis

Price=?

thermodynamics kinetics

T dec

=? (TGA) H

2 reabsorption (PCI) Lifetime=? (PCI)

Goal fulfilled

Efficient

Low–temperature

Reversible

Terrorist–proof

Solid Hydrogen

Store

Electronegativity perturbation vs the H…H coupling equilibrium

------------------------------------------------------------------

CH

4

: Gas, T melt

= –183 o C, T dec

= +680 o C

NH

4

+ BH

4

–

: Solid, T dec

= –40 o C

------------------------------------------------------------------

Cyclohexane is thermally stable liquid

[GaH

2

NH

2

]

3 decomposes at +150 o C to GaN and H

2

------------------------------------------------------------------

Benzene C

6

H

6

:

H f

°gas = +82.93 kJ mol –1

Borazine N

3

B

3

H

6

:

H f

°gas = –510.03 kJ mol –1

------------------------------------------------------------------

Conclusions

1. One should preferably play the H

-

I /H

2 equilibrium (metal hydrides)

2. Use light weight hydrides of strongly electropositive elements

(thermodynamically reversible) as a main hydrogen store.

3. Play on the electronegativity of a metal center by use of various ligands (including additional hydride ligands).

4. Use compounds of more electronegative metals as catalyst of H

2 evolution. Tune T dec

.

5. Provide that catalyst is not irreversibly reduced by hydrogen store, and by corresponding metal product.

6. Attempt play on the (H +1 ,H

–1

)/H

2 equilibrium if price of hydrogen store is very low (irreversibility does not matter) and if environment pollution is small. Forget the plasma induced H 0 reabsorption.

7. Try to solve the problem asap.

Hydrogen storage in carbon: graphite, fullerenes, nanotubes.

Non–reproducible claims of: i) Up to 13 wt % H in single wall nanotubes

( Nature 1997 , 386 , 377; Science 1999 , 286 ,

1127, Carbon 1999 , 37 , 1649) ii) Up to 20 wt % H in alkali metal–doped nanotubes ( Science 1999 , 285 , 91).

Problems: i) Lack of homogenity ii) Low active material content iii) High price of C nanotubes (CNT) iv) Simple graphitic sheets & doped graphite: low H storage efficiency v) Fullerenes: irreversible storage C

60

H

44

.

Modification: inorganic nanotubes

4 wt % H at 9 bar in ‘collapsed BN_NTs

( J. Amer. Chem. Soc. 2002 , 124 , 14550).

(Photo)electrolysis of water h

bateria słoneczna inne odnawialne E elektryczność

H

H

2

2

O

O

2 h

TiO

2

:C – 10 times better efficiency of photoelectrolytic

Utsira (Norway) 2003

Similar projects: splitting of water than pure i) windy islands of

TiO

2

(Nature, 2002 ) northern

Scotland, ii) sunny costs of

H

2

O

Florida, iii) and geothermal energy (Iceland – model hydrogen energy-based EU society!)

Activation of C–H, C–C, H–H and N

N bonds.

:

Oxidative & non–oxidative C–H bond activation:

M n+ [L] + H–CH

3

M (n+2)+ [L](CH

3

–

)(H

–

), same for H–C

6

H

5

M n+ [L](

:

H

–

) + H–CH=CH

2

M n+ [L](C

2

H

5

–

), M=Ru,Rh,Ta etc.

similar scheme for the C–C and

H–H bonds vide: agostic interactions

C=O & C

O bond activation:

O=C=O

–O–(C=O)–

|C

O|

–(C=O)–

Review on C–H activation:

Nature 417 (2002) 507–514

heterolytic activation homolytic activation

Complexes of molecular H–H.

Complexes of molecular N

N.

Find out more – Be up to date!

Hubbert’s peak & energy consumption:

• http://www.hubbertpeak.com/midpoint.htm

• http://www.trenton.edu/~energy/altfuel/Hydrogen.htm

• http://www.oilcrisis.com/laherrere/opec95.htm

• http://www.eia.doe.gov/oiaf/ieo/index.html

• http://www.energy.gov/dataandprices/index.html

• http://www.cato.org/pubs/pas/pa-280.html

Hydrogen production & storage:

• http://www.eren.doe.gov/hydrogen/basics.html

• http://www.eren.doe.gov/RE/hydrogen.html

• http://www.ornl.gov/ORNL/Energy_Eff/power-h2.html

• http://www.clean-air.org/ahafaq.html

• http://www.etde.org/html/hyd/hydhome.html

• http://starfire.ne.uiuc.edu/~ne201/1995/archer/hydro.html

• http://refining.dis.anl.gov/oit/toc/h2proc_8.html

• http://www.hydrogen.org/Wissen/NHF97.htm#4. Hydrogen Storage

• http://naftp.nrcce.wvu.edu/techinfo/altfuels/H2/Hydrogen.html

• http://ceh.sric.sri.com/Public/Reports/743.5000/

• http://home.powertech.no/magneh/meyer/hydrogen.htm

• http://www.e-sources.com/hydrogen/storage.html

• http://www.h2eco.org/

Press & news:

• http://www.hfcletter.com/

• http://www.h2fc.com/defaultNS4.html

• http://www.cnn.com/2000/NATURE/09/15/hydrogen.car/

• http://www.csmonitor.com/2002/0131/p13s01-stss.html

• http://www.chemweb.com/alchem/articles/1023977425407.html

Find out more – cd.

Scientific programs:

• http://www.ca.sandia.gov/CRF/03_hydrogen.html

• http://www.nrel.gov/nrel_research.html

• http://www.bham.ac.uk/FUCHSIA/home.htm

• http://www.spacefuture.com/archive/liquid_hydrogen_industry_a_key_for_space_tourism.shtml

• http://www.eren.doe.gov/

• http://www.bbsrc.ac.uk/science/initiatives/supergen.html

• http://www-ew.ike.uni-stuttgart.de/ewproject/ewktr821e.htm

Companies:

• http://www.jmcusa.com/mh1.html

• http://www.ergenics.com/

• http://www.ovonic.com/

• http://www.shell.com/home/Framework?siteId=hydrogen-en

• http://www.genesis.rutgers.edu/Partners/millenium.html

• http://www.azhydrogen.com/mg_25.html

• http://www.ballard.com/

• http://www.multishop.pp.ru/dmoz/Science/Technology/Energy/Hydrogen

• http://www.uscar.org/pngv/

• http://www.herahydrogen.com/flash.html

• http://www.ballard.com/tD.asp?pgid=32&dbid=0

Fuel cells:

• http://inventors.about.com/library/weekly/aa090299.htm?once=true&

• http://rhlx01.rz.fht-esslingen.de/projects/alt_energy/storage/fuelcell/fuelcell.html

Conferences:

• http://www.grc.uri.edu/programs/2001/hydrmet.htm