Evidence Based Medicine

advertisement

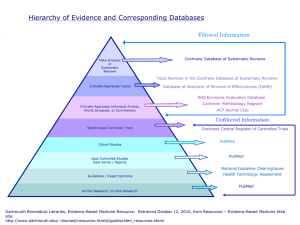

Evidence Based Medicine Lecture Sandra A. Martin, M.L.I.S. Health Sciences Resource Coordinator Instructor of Library Services John Vaughan Library Room 305B marti004@nsuok.edu – 918-444-3263 Existing knowledge can prevent… •Waste •Errors •Poor quality clinical care •Poor patient experience •Adoption of interventions of low value •Failure to adopt interventions of high value Source: Sir Muir Gray, Chief Knowledge Officer of Britain’s National Health Service. Quoted on http://www.nks.nhs.uk/. Harmful practices once supported by expert opinion Time period Accepted practice Shown to be harmful Impact on clinical practice From 500 bc Blood Letting 1820 Ceased in 1910 1957 Thalidomide for morning sickness in early pregnancy 1960 Withdrawn when first case report of severe malformations appeared From 1900 Bed rest for acute low back pain 1986 Still advised by some doctors 1960s Benzodiazepines for mild anxiety 1975 “Diazepam” prescribing fell in 1990s due to severe dependence and withdrawal symptoms Late 1990s Cox-2 inhibitors to treat arthritis 2004 Withdrawn following legal cases in the US Source: Adapted from How to read a paper: the basics of evidence-based medicine. 4th edition. By Trisha Greenhalgh. 2010 Blackwell Publishing Information Retrieval for Evidence Based Patient Care Using research findings versus conducting research Retrieving and evaluating information that has direct application to specific patient care problems Selecting resources that are current, valid and available at point-of-care Developing search strategies that are feasible within time constraints of clinical practice Learning Objectives At the end of the presentation, you will be able to: • Define evidence-based medicine (EBM) • Understand the Five Steps to practice EBM • Use the 6S hierarchy to conduct an efficient search for the best evidence • Access online pre-appraised resources • Locate print and online tools to assist in critical appraisal of individual studies • Practice the Five Steps in clinical settings What is EBM? www.cebm.net “Evidence-based medicine is the integration of best research evidence with clinical expertise and patient values” Patient Concerns EBMClinical Best research evidence Expertise Sackett DL, Rosenberg WMC, Gray JAM, Haynes RB, Richardson WS: Evidence based medicine: what it is and what it isn’t. BMJ 1996;312:71-2. Evolution of EBM in the Literature Term first appeared in the literature in a 1991 editorial in ACP Journal Club Volume 114, Mar-April 1991, pp A-16 Seminal article by the Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group published in JAMA Volume 268, No. 17, 1992, pp 2420-2425 Fundamentally new approach becomes widely recognized JAMA published a series of Users’ Guides to the Medical Literature that served as the first learning tools Courses were developed in residency training and medical school curricula The first handbook, Evidence-Based Medicine: How to practice and teach EBM, by Sackett, et al, was published in 1996. Fourth edition published in 2010. New York Times listed EBM as one of its ideas of the year in 2001 BMJ listed EBM as one of the 15 greatest medical milestones since 1840 Integration of EBM into medical school curricula patient-doctor courses EBM Process – 5 Steps 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. ASK: Convert need for information into answerable question ACQUIRE: Find best evidence to answer the question APPRAISE: Critically appraise evidence for validity, impact, and applicability APPLY: Integrate evidence with clinical expertise and patient values ASSESS: Evaluate own effectiveness New Approach Requires New Skills Clinical question formulation Search and retrieval of best evidence Critical appraisal of study methods to determine validity of results Background v Foreground Knowledge Both types of knowledge needed Varies over time Depends on experience with condition Point A: Student – limited experience Point B: Resident – growing clinical experience Point C: Attending – extensive experience Note: Diagonal line shows “we’re never too green to learn foreground knowledge, nor too experienced to outlive the need for background knowledge” Source: Evidence-based medicine: how to practice and teach it. 4th edition. By Straus, et. al. Churchill Livingstone Elsevier Answerable Questions Arise in patient care setting and are: Important to the patient’s well being Fill gaps in your clinical knowledge Feasible to answer in time available Clinical Questions Four Common Types Therapy/prevention Diagnosis Etiology Prognosis Therapy Question Example In patients with primary open angle glaucoma or ocular hypertension [Patient/Population], do topical medications to reduce intraocular pressure [Intervention] versus no treatment [Comparison Intervention], delay visual field defect progression [Outcome]? PICO Model PICO- Patient or population Intervention Comparison Intervention Outcome Possible Search Terms Primary open angle glaucoma, POAG, Ocular hypertension, OHT, topical medications, intraocular pressure, IOP, visual fields, VF Evidence Based Retrieval 1. Find the answer that is supported by valid studies appropriate to the type of question and that is available in a timely manner. 2. Requires search terms plus best study design for question plus highest level of evidence Best Study Design for Type of Question Type of Question Study Design Therapy/prevention Randomized controlled trials Diagnosis Prospective cohort, blind comparison to a gold standard Prognosis Cohort, Case Control, Case Series Etiology/Harm Cohort, Case Control, Case Series Is All Evidence Created Equal? Small portion of medical literature is immediately useful to answer clinical questions Understanding “wedge or pyramid of evidence” is helpful in finding highest level of evidence High levels of evidence may not exist for all questions due to nature of medical problems and research limitations As you move up the pyramid the amount of available literature decreases, but it increases in its relevance to the clinical setting. Source: Sackett, D.L., Richardson, W.S., Rosenberg, W.M.C., & Haynes, R.B. (1996). Evidence-Based Medicine: How to practice and teach EBM. London: Churchill-Livingstone. Levels of Evidence Grade the quality of evidence based on the design of the clinical study Variety of hierarchies in use American Academy of Family Physicians SORT Level A Systematic reviews of randomized controlled trials including metaanalyses Good-quality randomized controlled trials Level B Good-quality nonrandomized clinical trials Systematic reviews not in Level A Lower-quality randomized controlled trials not in Level A Other types of study: case control studies, clinical cohort studies, cross sectional studies, retrospective studies, and uncontrolled studies Level C Evidence-based consensus statements and expert guidelines DynaMed and FirstConsult Hierarchy of Published Evidence for Intervention Studies Level of Evidence Description Study Example 1 Randomized clinical trial with low study errors or a metaanalysis Optic neuritis treatment trial N Engl J Med. 1992; 326:581-588 2 Randomized clinical trial with high study errors Scatter laser photocoagulation for occult choroidal neovascularization Arch Ophthalmol. 1996; 114:14561464 3 Clinical trial with a control group, with nonrandom treatment allocation Thrombolytic therapy for acute retinal arterial occlusion Am J Ophthalmol. 1992; 113:429-434 4 Intervention case series Macular translocation surgery for the treatment of CNVM and AMD Am J Ophthalmol. 1968; 66:597-603 5 Interventional case report Removal of a choroidal neovascular membrane Retina. 1994; 14:125-129 Key developments that streamlined the practice of EBM Advances in ease of accessing and understanding information Development of preprocessed (preappraised) tools Improvements in search interfaces to MEDLINE Collaboration between EBM Working Group and National Library of Medicine in development of hedges, “clinical queries” tool, that filters search results to specific study types and levels of evidence Dissemination of systematic reviews of primary studies and growth of the Cochrane Collaboration 4S Hierarchy Highest Level of Evidence - Critically Appraised Content Evidence Based Summaries Dynamed, Clinical Key, First Consult, UptoDate ACP Journal Club, DARE Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews Clinical Key & Ovid MEDLINE limited to Study Types and Clinical Queries SOURCE: Haynes, R. B. (2001). Of studies, syntheses, synopses, and systems: the “4S” evolution of services for finding current best evidence. Evidence-Based Medicine, 6 (2), 36-38. Retrieved 2-07-07 from http://ebm.bmj.com/cgi/reprint/6/2/36 6S Hierarchy • Summaries: • • • Clinical Key First Consult Dynamed New Resource – Clinical Key Full text access to 1,000 books and 500 journals in every medical and surgical specialty Ophthalmology – Over 60 full text books Includes 12 Content Types Access to information at all levels from topic overview to evidence-based data in one search Smart search engine matches first few letters of search word/words to relevant clinical content No complicated search strategies or Boolean connectors Easier than Google – but with reliable, evidence-based results Clinical Key includes 3 Levels Plus Books and Overviews Summaries, Synthesis, Studies Summaries • FirstConsult – Available through NSU subscription to Clinical Key for iPhone or iPad only – Create a personal account in Clinical Key – Download the app from the Apple app store – Login with your Clinical Key username and password – Summaries are detailed and include sections on Differential Diagnosis – Eyes and Vision topics well covered Summaries • DynaMed – Summaries for more than 3,000 topics – Monitors >500 medical journals and systematic review databases – Updated daily – Each article evaluated for clinical relevance and scientific validity – Includes “graded evidence” Glaucoma Summary Evidence-based answer found in 1 minute, 39 seconds Summaries • UptoDate – Evidence based summaries of over 9,500 topics in over 20 specialties, over 250,000 references, and drug database – Ophthalmology not one of the specialties – Good for information on systemic conditions – Updated continuously Clinical Question “In hypertensive patients older than 75 with atrial fibrillation (P), does the use of warfarin (I), compared to aspirin (C), result in fewer strokes (O)?” 1:54 Syntheses • Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (DSR) – Part of the Cochrane Library (1996) – 916 completed reviews, 1905 protocols – Among the highest level of evidence upon which to base treatment decisions – Includes Dx since 2008 – Eyes & Vision Research Group • Contains over 165 reviews Systematic Review Analyzes data from several primary studies to answer a specific clinical question Provides search strategies and resources used to locate studies Includes specific inclusion and exclusion criteria (results in less bias) Meta-Analysis (subclass) statistically summarizes results of several individual studies Access full text of Cochrane reviews in OVID Cochrane DSR Review found in 15 seconds Copyright: The Cochrane Library, Copyright 2009, The Cochrane Collaboration Appraisal Required by User Primary (Original) Studies Articles that report results of original research investigations Conclusions supported by data and reproducible methodology Require time to acquire and appraise Good Sources: Ovid MEDLINE and Clinical Key When to search for original studies If the other “S’s” don’t provide the answer, search for original studies “Do it yourself” appraisal territory You must appraise quality of the study or find analysis in evidence based summary Limit to “Study Type” in Clinical Key or “Clinical Queries” in Ovid MEDLINE Databases • MEDLINE – Premiere biomedical database from the NLM (National Library of Medicine) – Covers 1946-present – Indexes >4000 international biomedical journals – Full text available for many articles – Access through Ovid MEDLINE Indexing Search Query Boolean Connectors MEDLINE Search Limits • Limit search results to study type – Randomized controlled trials – Clinical trials • In OVID, limit by “Clinical Queries” • Appraise study for validity and relevance Ovid MEDLINE Clinical Queries Levels of Evidence in Ovid based on AAFP SORT Level A = “Specificity” in Ovid Clinical Queries Systematic reviews of randomized controlled trials including metaanalyses Good-quality randomized controlled trials Level B = “Sensitivity” in Ovid Clinical Queries Good-quality nonrandomized clinical trials Systematic reviews not in Level A Lower-quality randomized controlled trials not in Level A Other types of study: case control studies, clinical cohort studies, cross sectional studies, retrospective studies, and uncontrolled studies Level C Evidence-based consensus statements and expert guidelines Take Home Points Focused clinical question (PICO) reveals your search terms Start your search at top of 6S hierarchy and work down Be aware of the filter, i.e., levels of evidence, speed of updating Look at more than one resource in the hierarchy. Findings may differ Apply in clinical settings; Assess your progress