cost for decision making

advertisement

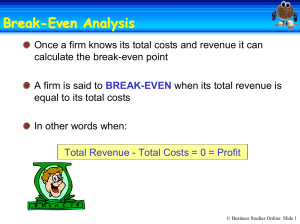

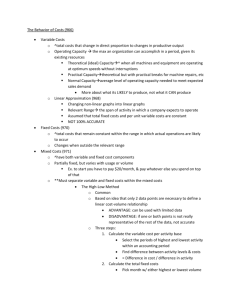

COST FOR DECISION MAKING 1.1 Definition of Decision Making Decision making is the essence of all management activity and naturally, accounting plays a role in informing decisions. Making correct decisions is one of the most important tasks of a successful manager. Every decision involves a choice between at least two alternatives. Decision making is a process of choosing among a set of alternative courses of action with a view to attain the firm’s objectives. The costing system of any organisation is integral in the decision making process. The costing system of the firm, for which the accountant is responsible, has to report on the cost of products and services from which decisions to discontinue redesign, make or buy, etc. have to be made. The quality of the decision generally reflects the quality of the information provided to management by the accountant. Decision making is a future oriented activity; it involves forecasting and planning. What has happened in the past is only of historical value. The function of decision making is to choose alternatives for the future. There two perquisites for making efficient and effective decisions. First, of all possible alternatives should be carefully delineated. A manager may choose a best alternative form among the alternatives considered by him; but he may fail to consider some other available alternatives which may be better than the chosen alternative. Second, the objective should be correctly set. A wrong objective can lead to the adoption of undesirable and unprofitable course of action. The decision process may be complicated by volumes of data, irrelevant data, incomplete information, an unlimited array of alternatives, etc. The role of the managerial accountant in this process is often that of a gatherer and summarizer of relevant information rather than the ultimate decision maker. In this regard, cost data are the most crucial quantitative factors needed for making decisions. A distinction between relevant and irrelevant cost data should be drawn. All costs are not relevant in decision making. A cost is relevant if it is pertinent to the decision under consideration. A relevant cost is also a cost that differs between alternatives. In other words, cost which varies as a consequence of the decision is a relevant cost. A relevant cost for a particular decision is one that changes if an alternative course of action is taken. Relevant costs are also called differential costs. Any cost that does not differ between alternatives is irrelevant and can be ignored in a decision. Sunk costs (costs already irrevocably incurred) are always irrelevant since they will be the same for any alternative. In addition, an avoidable cost which can be eliminated (in whole or in part) by choosing one alternative over another is a relevant cost. Relevant cost includes concepts such as differential cost and marginal cost and contrition approach. To identify which costs are relevant in a particular situation, take this three step approach: 1. Eliminate sunk costs 2. Eliminate costs that do not differ between alternatives 3. Compare the remaining costs and benefits that do differ between alternatives to make the proper decision 1.1.1 Decision Making Process A manager should take the following steps to make decision s intelligently and skilfully; 1. Definition of objectives/ Identification of problems: The first stage in decision making process should be to specify the goal and objectives of the organisation. The basic objective of most businesses is to maximise profit or shareholders’ wealth. Also, the firm should recognise the problems for which the decisions have to be made. 2. Search for Alternatives: The firm must search for a range of possible alternatives or courses of action that might help achieve the objectives of the firm or solve the problem on hand. For decision making be successful, the firm must be able to identify all available alternatives. It must have information in order to make a valid choice between the alternative courses of action. The search for alternatives involves information concerning future opportunities and environments 3. Evaluation of Alternatives: The firm should evaluate the alternatives by analysing the costs and benefits. All alternatives should be assessed on their own merits to ascertain their contribution to the attainment of the objectives of the firm. In this regard several techniques or methodologies can be used to evaluate the viability of the various courses of action available to the firm. 4. Selection of Alternative: Once alternative courses of action have been selected, they should be implemented. Implementation forms a crucial aspect of the decision making process in that no matter how good the decision is, if not implemented, it will not yield the necessary results. 5. Comparison of Actual to Planned Outcome: After the selected alternative courses of action have been implemented, the outcome of the implemented course of action is compared to the planned to ascertain whether the alternative has generated the desired results. 6. Taking Corrective Measures: The firm should take corrective actions to correct any deviations in the implemented courses of action. 1.2 Relevant Information for Decision Making Relevant costs are costs which are influenced by decisions taken. Therefore all other costs are irrelevant. The same distinction can apply to information concerning revenues. Costs generally fixed but variable for the period of the decision are relevant while all generally variable but fixed for the period of the decision are irrelevant. It is important to appreciate that all in all decision analysis economic values are used and not historical costs which mean that it will not be possible to extract this data directly from the financial accounts. Some values in the financial accounts will not be relevant. 1.2.1 Guidelines for Determining Relevant Costs 1. Materials: If raw materials has been acquired and held in the stock records at its purchase cost this will be the purposes of the financial accounting records. This purchase cost is not the relevant cost for material for any future decision. The relevant cost of the material will be determined by whatever courses of action are opened to the firm. If the material to be used in the production of a product is in regular use, the relevant cost is the future replacement cost, on the basis that once applied to the chosen decision a further material purchase will be needed to restore the company to its original state. If, on the other hand the company cannot conceive of a use for the material except for its use on the product then the relevant cost to be used is the anticipated disposal value of the material (realisable value)when evaluating and costing the product. To incorporate this disposal value into a costing of the product is to use it as an opportunity cost. Finally, if the material cannot be disposed of and the only option is to use it on the product then the relevant cost is zero, this material can be used for nothing. Incidentally, its use on the product saved the company from having to pay for disposal of the material. Notice in no case is the original acquisition cost used. If any of the future costs and benefits have applying to them some contractual obligation this is not relevant. In other words, the company is already committed to them, ay due to a past contract of some kind, then these committed future costs and benefits are not relevant to the decision at hand. 2. Labour: The principle here is if there is spare capacity then the labour cost will only be relevant if either extra hand were contracted or overtime work was done by the workers. If there is no spare capacity but the production of another product has to be abandoned to create space, then the relevant cost is the contribution from alternative products which must be abandoned to create spare capacity. This is against the backdrop that contracts of employment and acknowledged social responsibility of employers it is possible that reduction, removal or manipulation of a work force may not be easy or cost free. 3. Overheads: Only future costs and benefits are relevant. Hence only those overheads that vary as a direct result of the decision taken are relevant overheads. For instance, depreciation, an overhead cost is never relevant to a decision about its use or non-use. Short-term management decisions can be made using full costing, variable costing, or incremental analysis. Full costing often involves preparing side-by-side income statements and identifying the differences. Incremental analysis is most often the straightest forward, the shortest, the easiest, and the best approach to decision making because it helps managers focus on the relevant parts of a decision. A manager that uses full or variable costing wastes a lot of time capturing and listing costs that will not impact the decision at hand. This is because they do not differ between decisions. Two potential problems that should be avoided in relevant cost analysis are (i) Do not assume all variable costs are relevant and all fixed costs are irrelevant. (ii) Do not use unit cost data directly. It can mislead decision makers because a. it may include irrelevant costs, and b. comparisons of unit costs computed at different output levels lead to erroneous conclusions 1.3 Types of Decisions Relevant cost and revenue information can be used to make decisions with regards to; a. Make, lease or buy b. Make special orders c. Sell or process further d. Keep or drop products e. Multiple products and limited resources 1.3.1 Cost Analysis in Make, Lease or Buy Decisions Management sometimes may have to make a choice between manufacturing the component parts of a product, or buying them from outside. Such a situation of make or buy decision may arise whenever the firm has the idle plant capacity and the technical capacity of manufacturing the component parts. In a make or buy situation, the decision will hinge upon both qualitative and quantitative factors qualitative consideration include product quality and the necessity for long-run business relationships with subcontractors. The key quantitative factors are the differential costs of the make and buy alternatives and the consequences of the alternative uses of the idle facilities. These factors are best seen through the relevant cost approach. The relevant cost of the buying alternative will include the purchase price and the ordering costs. Costs relevant for the make alternative would include the variable costs, viz, direct material, direct labour and variable overheads and those fixed costs which are avoidable. If fixed costs are expected to remain unaltered, hey would be irrelevant in the make or buy decision. The firm should also consider the alternative uses of the idle facilities. If a more profitable use than manufacturing the parts exists, then the firm may procure the parts from outside and use facilities for the more profitable alternatives. Also, you can analyze the costs of the lease or buy problem through discounted cash flows analysis. This analysis compares the cost of each alternative by considering the timing of the payments, tax benefits, and interest rate on a loan, the lease rate, and other financial arrangements. To make t analysis you must first make certain assumptions about the economic life of the equipment, salvage value, and depreciation. A straight cash purchase using the firm’s existing funds will almost be more expensive than the lease or loan/buy options because of the loss of the use of funds. Reasons to Buy from Outside Flexibility to meet urgent demand of customers; Overcome limiting factor problem Concentrate on its own core competencies; Take advantage of the specialist skill and expertise of the outsiders; Overcome production bottleneck and Solve seasonal demand problem Illustration 1 Suppose a firm manufactures 1000 units of a part and has the following cost structure: Cost Per Unit Cost (GH¢) Cost of 1000 units (GH¢) Direct materials 2 2000 Direct labour 6 6000 Variable overheads 3 3000 Fixed Overheads 4 4000 Total 15 15000 An outside supplier offers to the firm to sell the parts for GH¢13 each. Should the company accept the offer? One may argue that the answer is obvious. The cost of buying the part GH¢1 is less than the cost of manufacturing the part (GH¢15), therefore, the part should be bought. The comparison is not correct. To decide correctly, the differential manufacturing cost of GH¢4000 should be considered, which may be unavoidable, that is, it will have to be incurred whether the part is made or bought from outside. Then those fixed costs are not relevant in making the comparison. The relevant cost of manufacturing part, thus, would be GH¢11 only. If we assume that the idle facilities cannot be put to an alternative use, then the firm should decide to me the part rather than buy it from outside. Illustration 2 For many years Lansing Company has purchased the starters that it installs in its standard line of garden tractors. Due to a reduction in output, the company has idle capacity that could be used to produce the starters. The chief engineer has recommended against this move, however, pointing out that the cost to produce the starters would be greater than the current GH¢10.00 per unit purchase price. The company’s unit product cost, based on a production level of 60,000 starters per year, is as follows: Cost Direct materials Make (GH¢) 4 Direct labour 2.75 Variable manufacturing overheads 0.5 Fixed manufacturing overheads, traceable (GH¢) 3 180,000 2.25 135,000 Fixed manufacturing overheads (allocated based on direct labour hours) 12.5 An outside supplier has offered to supply the starter to Lansing for only GH¢10.00 per starter. One-third of the traceable fixed manufacturing costs represent supervisory salaries and other costs that can be eliminated if the starters are purchased. The other two-thirds of the traceable fixed manufacturing costs is depreciation of special manufacturing equipment that has no resale value. The decision would have no effect on the common fixed costs of the company and the space being used to produce the parts would otherwise be idle. Required: Should the company make or buy the starters? Solution Relevant Cost Cost Direct materials Make (GH¢) Buy(GH¢) 4 Direct labour 2.75 Variable manufacturing overheads 0.5 Fixed manufacturing overheads, traceable 1 Purchase Price 0 10 8.25 10 Units produced 60,000 60,000 Total cost 495,000 600,000 Total relevant cost The two-thirds of the traceable fixed manufacturing overhead costs that cannot be eliminated, and all of the common fixed manufacturing overhead costs, are irrelevant. The company would save GH¢105,000 per year by continuing to make the parts itself. In other words, profits would decline by GH¢105,000 per year if the parts were purchased from the outside supplier. Illustration 3 Jackson Company is now making a small part that is used in one of its products. The company’s accounting department reports the following per unit costs of producing the part internally. Cost (GH¢) Direct materials 15 Direct labour 10 Variable manufacturing overheads 2 Fixed manufacturing overheads, traceable 4 Fixed manufacturing overheads(allocated) 5 Unit product cost 36 Depreciation of special equipment represents 75% of the traceable fixed manufacturing overhead cost with supervisory salaries representing the balance. The special equipment has no resale value and does not wear out through use. The supervisory salaries could be avoided if production of the part were discontinued. An outside supplier has offered to sell the part to Jackson Company for GH¢30 each, based on an order of 5,000 parts per year. Should Jackson Company accept this offer, or continue to make the parts internally? Solution Cost Make (GH¢) Buy (GH¢) Direct materials 15 Direct labour 10 Variable manufacturing overheads 2 Fixed manufacturing overheads, traceable 1 Purchase price 0 30 Unit product cost 28 30 5,000 5,000 140,000 150,000 Units produced Unit product cost Difference in favor of making: GH¢10,000. The depreciation on the equipment and common fixed overhead are not avoidable costs. Hence, they are not relevant in the decision making. Illustration 4 Moo Milk makes the 1-gallon plastic milk jugs used to package its premium goat’s milk. The company has been approached by a plastic molding company with an offer to produce the milk jugs at a cost of GH¢14.00 per thousand jugs. Moo’s president believes the company should continue to produce the jugs and the plant manager has recommended accepting the offer because the cost to produce the jugs is greater than the purchase price. The company’s cost to produce one thousand jugs is as follows: Cost (GH¢) Direct materials 4 Direct labour 2.75 Variable manufacturing overheads 3.5 Fixed manufacturing overheads, traceable 3 Fixed manufacturing overheads, common 2.25 Total Production Cost 15.75 One-half of the traceable fixed manufacturing costs represent supervisory salaries and other costs that can be eliminated if the milk jugs are purchased. The balance of the traceable fixed manufacturing costs is depreciation of manufacturing equipment that has no resale value. Some of the space being used to produce the milk jugs could be used to store empty jugs, eliminating a rented warehouse and reducing common fixed costs by 20%. The rest of the space could be rented to another company for GH¢30,000 per year. Moo Milk produces 10,000,000 milk jugs per year. Required: Should Moo Milk make or buy the milk jugs Solution Cost Direct materials Make (GH¢) 4 Direct labour 2.75 Variable manufacturing overheads 3.5 Fixed manufacturing overheads, traceable 1.5 Fixed manufacturing overheads, common 0.5 Purchase price Buy (GH¢) 0 14 Unit product cost 12.25 14 Units produced (in thousands) 10,000 10,000 Sub-total 125,500 140,000 Opportunity cost 30,000 0 Product cost 152,500 140,000 Difference in favour of buying: GH¢12,500. The opportunity cost changed the decision from making to buying the milk jugs. 1.3.2 Cost Analysis to Make Special Order Decisions Special order decisions involve determining whether a special order from a customer should be accepted. This type of decision is usually a one-time order that will not impact a company’s regular sales. Before considered a special order, the company must have idle capacity, i.e., it should have the ability to complete the special order without expanding its operations. In other words, it must have capacity that is sitting idle and not being currently used. The special order decision is based on the difference between the incremental revenue and the incremental costs. The profit from a special order equals the incremental revenue less the incremental costs. As long as the incremental revenue exceeds the incremental costs and present sales are unaffected, the special order should be accepted. Incremental revenues are the additional revenues generated from accepting the special order that generates additional sales of the product or service. It does not affect current sales as they will remain the same. Incremental costs are the additional costs incurred from accepting a special order. Variable product costs will always be incremental and cause profits to decline. Other variable costs of operations including selling costs like commissions and shipping costs will be relevant as well. Rarely will cost savings be a consideration in special order decisions. What Amounts Are Not Relevant in Special Order Decisions? All costs that will be incurred regardless if a special order decision is accepted or not are not relevant for special order decisions. Most often these will be fixed costs. Occasionally the acceptance of a special order could cause a change in some fixed costs. However this will be an obvious fact when you analyze the information concerning the special order. Sunk costs are not relevant with any special order decision process. When Should Special Orders Be Accepted? Special orders should be accepted only if: Incremental revenue exceeds incremental costs Present sales are unaffected The company has idle capacity to handle the order Special orders which do not meet these criteria should generally not be accepted. Of course, soft-benefits should be considered as well. Accept or Reject? If incremental revenues are less than incremental costs, reject the special order, unless qualitative characteristics overwhelmingly impact the decision. If incremental revenues are greater than incremental costs, accept the special order unless qualitative characteristics overwhelmingly impact the decision. If incremental revenues are equal to incremental costs, focus primarily on qualitative characteristics to assess the decision. Illustration 1 Tony’s T-shirts makes shirts for local soccer, baseball, basketball, and other sports teams. The owner, Tony, purchases the shirts and prints graphics on the shirts for each team. The graphics were designed several years ago, so design costs are no longer incurred. On average, Tony sells 1,000 shirts each month. Typical monthly financial data follow: Per Unit Total Monthly Data for 1000 (GH¢) Sales revenue shirts (GH¢) 20 20,000 Variable Costs: Direct materials 8 8,000 Direct labour 2 2,000 Manufacturing overhead 3 3,000 Total variable costs 13 13,000 Contribution margin 7 7,000 Fixed costs (rent, salaries etc) 4,000 Profit 3,000 The monthly information provided relates to the company’s routine monthly operations. A representative of the local high school recently approached Tony to ask about a one-time special order. The high school will be hosting a statewide track and field event and is willing to pay Tony’s T-shirts GH¢17 per shirt to make 200 custom T-shirts for the event. Because enough idle capacity exists to handle this order, it will not affect other sales. That is, Tony has the factory space and machinery available to produce more T-shirts. Tony incurs the same variable costs of GH¢13 per unit to produce the special order, and he will pay a firm GH¢600 to design the graphics that will be printed on the shirts. This special order will have no other effect on Tony’s monthly fixed costs. Should Tony accept the special order? Solution Reject Special Order Accept Special Order Differential GH¢ Sales revenue 20,000 23,400a - 3,400 Variable costs Contribution margin 13,000 7,000 15,600b 7,800 - 2,600 800 Fixed cost 4,000 4,600c - 600 Profit 3,000 3,200 - 200 a= GH¢ 23,400 = GH¢20,000 + (GH¢17 per shirt × 200 shirts). b= GH¢15,600 = GH¢13,000 + (GH¢13 × 200 shirts). c= GH¢ 4,600 = GH¢4,000 + GH¢600 cost for special order design. Result of Accepting Special Order Sales revenue increase 3,400 Variable costs increase Contribution margin increase -2,600 800 Fixed cost increase: graphics design -600 Profit increase from accepting special order 200 The table above shows the differential revenues and costs for the special order being considered. If Tony’s T-shirts accepts the special order, sales revenue will increase GH¢ 3,400 with a corresponding increase in variable costs of GH¢ 2,600. Fixed costs will increase by GH¢ 600 because design work is required for the special order. Thus profit will increase by GH¢ 200 (=GH¢ 3,400 − GH¢ 2,600 − GH¢ 600). Tony should therefore accept the special order offer. NB: In cases where the acceptance of the special order is going to affect the normal sales of the firm negatively, then the fall in sales as a result of the special order should be accounted for as opportunity cost. Salient points on Qualitative factor to consider: In the above case, we have assumed that there is spare capacity but it’s important to ensure that there is really sufficient capacity before agreeing on special order; ask whether there is any better alternative than accepting special order; by accepting special order, needs to ensure that this special order does not affect customer loyalty or affecting the status quo of the existing product, in the above case is product X. Basically, we should not endanger the existing products by wanting to utilize full production capacity. Illustration 2 Trojan Company produces a single product. The cost of producing and selling a single unit of this product at the company’s normal activity level of 8,000 units per year is: GH¢ Direct materials Direct labour 2.5 3 Variable manufacturing overheads 0.5 Fixed manufacturing overheads 4.25 Variable selling and administrative expense 1.5 Fixed selling and administrative expense 2 The normal selling price is GH¢15.00 per unit. The company’s capacity is 10,000 units per month. An order has been received from an overseas source for 2,000 units at the special price of GH¢12.00 per unit. This order would not affect regular sales. Required: a) If the order is accepted, how much will monthly profits increase or decrease? (The order will not change the company’s total fixed costs.) b) Assume the company has 500 units of this product left over from last year that are vastly inferior to the current model. The units must be sold through regular channels at reduced prices. What unit cost is relevant for establishing a minimum selling price for these units? Explain. Solution a. GH¢ Selling price Direct materials Direct labour GH¢ 12 2.5 3 Variable manufacturing overheads 0.5 Fixed manufacturing overheads 4.25 Variable selling and administrative expense 1.5 Total variable expenses 7.5 Contribution margin 4.5 Units sold 2000 Total Contribution margin 9000 b. The relevant cost is GH¢1.50 (the variable selling and administrative costs). All other variable costs are sunk, since the units have already been produced. The fixed costs would not be relevant, since they will not be affected by the sale of leftover units. 1.3.3 Cost Analysis in the Decision to Sell before or after Additional Processing In some manufacturing processes, several intermediate products are produced from a single input. A firm may manufacture and sell an intermediate product. If the facilities are available,, it may want to process the product further d sell it as completely processed product. To choose between sell and process further alternatives, the firm should see the impact of differential cost of further processing on contribution. If the firm obtains more contribution by selling the completed product, it should process further. In this sell or process further decision making, joint costs are considered irrelevant since the joint costs have already been incurred at the time of the decision and therefore represent sunk costs. The decision will rely exclusively on additional revenue compared to the additional costs incurred due to further processing. Additional processing decisions are based on the differences between the incremental revenues and the incremental costs. Incremental revenues represent the difference between the revenues generated from selling the product 'as is,' often partially complete, and the revenues generated after processing the product further to increase its saleability. Incremental costs are the additional costs incurred from further processing. Costs associated with producing the product up to the decision point are already incurred in the past and are considered sunk. All sunk costs are irrelevant. Evaluating the Decision If incremental revenues are less than incremental costs, the product should be sold 'as is.' If incremental revenues equal incremental costs, qualitative effects must be used to make the decision. If incremental revenues are greater than incremental costs, the product should be processed further. Regardless if the choice is to sell as-is or process further; a company should always consider the 'touchy-feely' aspects of decision making effects. These include employee morale, goodwill to the community, environmental effects, feasibility, resource availability, etc. A sell-or-process-further analysis can be carried out in three different ways: Incremental (or Differential) Approach calculates the difference between the additional revenues and the additional costs of further processing. If the difference is positive the product must be processed further, otherwise not. Opportunity Cost Approach calculates the difference between net revenue from further processed product and the opportunity cost of not selling the product at split-off point. If the difference is positive, further processing will increase profits. Total Project Approach (or the comparative statement approach) compares the profit statements of both options (i.e. selling or further processing) separately for each product. The option generating higher profit is chosen Illustration 1 Product A and B are produced in a joint process. At split-off point, Product A is complete whereas product B can be process further. The following additional information is available: Product Quantity in Units A B 5000 10000 10 2.5 Selling Price per Unit: At Split-Off If Processed further 5 Costs After Split-Off 20000 Fixed selling and administrative expense Perform sell-or-process-further analysis for product B. Solution Method 1 (Incremental Approach) GH¢ Incremental Revenue 25,000 Incremental Costs 20,000 Increase in Profits Due to Further Processing 5,000 Method 2 (Opportunity Cost Approach) GH¢ Sales in Case of Further Processing 50,000 Costs: Additional Costs 20,000 Opportunity Cost of Not Selling at Split-Off 25,000 Gain on Further Processing 5,000 Method 3 (Total Approach) Revenue Split-Off Further Point Processed GH¢25,000 50,000 0 20,000 25,000 30,000 Costs Net Revenue Gain from Further Processing 5,000 Illustration 2 A market decline for staplers has caused Sobo Company to drop its selling price per stapler from GH¢15 to GH¢12. There are 8,000 staplers in work in process (partially finished) that have costs of GH¢7.80 per unit associated with them. Sobo can sell these units in their current state for GH¢9.00 each. It will cost Sobo GH¢1.70 per unit to complete the staplers in process, so that they can be sold for GH¢12 each. a. How much is the incremental cost if processed further? b. Use your answer to part A to calculate incremental profit or loss. c. List any amounts given in the problem that Sobo should label as ‘sunk’ costs. Solution a. Incremental cost: 8,000 x GH¢1.70 = GH¢13,600 Incremental cost is the difference in cost if the staplers are 'processed further', i.e., completed. The costs incurred in the past, the GH¢7.80 per stapler is not relevant because it will be the same no matter if the staplers are processed further or sold as-is. This past cost is a sunk cost, and sunk costs are never relevant because the cost cannot be changed and is the same regardless if processed further or sold as-is. b. Incremental revenue (GH¢12 -9)*8,000 Incremental costs (part A) Incremental profit if processed further GH¢24,000 (13,600) 10,400 Because profits increase, the staplers should be processed further. Revenue will increase by GH¢3 per unit and costs will increase by GH¢1.70 per unit netting a profit increase of GH¢10,400. Because this is an incremental analysis, you must only consider the incremental costs and incremental revenue. c. List any amounts given in the problem that Sobo should label as ‘sunk’ costs. Only one amount is sunk, the GH¢7.80 cost of producing the products to their current state. This amount has already been incurred and won't change regardless of the decision made. 1.3.4 Joint Product Cost Decisions In some manufacturing processes, several end products are produced from a single input. Such end products are known as joint products. The costs associated with making these products up to the point where they can be recognized as separate products (the split-off point) are called joint product costs. Cost allocation problem Joint product costs are really common costs that are incurred to simultaneously produce a variety of end products. Unfortunately, these common costs are routinely allocated to the joint products. Allocated joint product costs are often misinterpreted as costs that could be avoided by producing less of one of the joint products. However, joint product costs can only be avoided by producing less of all of the joint products simultaneously. If any of the joint products is made, then all of the joint product costs up to the split-off point will have to be incurred. Therefore, in deciding on whether to produce or not produce a particular product that forms part of the joint products, we use only costs that are incurred in the production of that product and the revenue generated after the spilt-off point. In this case, the differential or incremental approach is widely used. Because the analysis is done by taking account of only increases in revenue and cost after the split-off point. 1.3.5 Cost Analysis in the Decision to Keep or Drop Products or Services Management is sometimes faced with the problem of dropping an unprofitable product or department. The decision to drop an old product line or add a new one must take into account both qualitative and quantitative factors. However, any final decision should be based primarily on the impact the decision would have on contribution margin or net income. Therefore the amount of common fixed costs typically continues regardless of the decision thus cannot be saved by dropping the product line to which it is distributed Just like other types of short term decisions, segment/product decisions can be made using either full costing or incremental analysis. Full costing often involves preparing two side-byside income statements and looking at the differences. Incremental analysis is most often the most straight-forward, the shortest, the easiest, and the best approach because it helps managers focus on the relevant parts of a decision. A manager that uses full costing wastes a lot of time looking at costs that will not differ between two decisions. We will focus primarily on whether a product line or segment should be dropped. Decisions If the decrease in revenue > decrease in costs, do not drop the product line/services. If the decrease in revenue < decrease in costs, drop the product line/services. If the decrease in revenue = decrease in costs, consider qualitative issues alone. Fixed Costs Fixed costs in total remain the same regardless of activity. The same is generally true regardless of how many product lines or segments a company has. Fixed costs fall into two types that can help decide if they are relevant or not for add or drop decisions: Common fixed costs Costs that are not traceable to a particular product or segment; Costs that benefit more than one product or segment; they are allocated/distributed amongst a number of product/segments. Not relevant because they continue whether the product or segment is dropped or not. If one product or segment is dropped, total common fixed costs must be reallocated to remaining products or segments. Direct fixed costs Costs that pertain specifically to one product or segment that are avoidable if that product/segment is dropped Relevant because they can be avoided if the product or segment is dropped Approaches Two basic approaches can be used to analyze data in this type of decision. 1. Compare contribution margins and fixed costs. A segment should be added only if the increase in total contribution margin is greater than the increase in fixed cost. A segment should be dropped only if the decrease in total contribution margin is less than the decrease in fixed cost. 2. Compare net incomes. A second approach is to calculate the total net income under each alternative. The alternative with the highest net income is preferred. This approach requires more information than the first approach since costs and revenues that don't differ between the alternatives must be included in the analysis when the net incomes are compared. Beware of allocated common costs. Allocated common costs can make a segment look unprofitable even though dropping the segment might result in a decrease in overall company net operating income. Allocated costs that would not be affected by a decision are irrelevant and should be ignored in a decision relating to adding or dropping a segment. Illustration 1 A company has three products: Product A, Product B and Product C. Income statements of the three product lines for the latest month are given below: Product Line A B C GH¢467,000 GH¢314,000 GH¢598,000 Variable Costs 241,000 169,000 321,000 Contribution Margin 226,000 145,000 277,000 Direct Fixed Costs 91,000 86,000 112,000 Allocated Fixed Costs 93,000 62,000 120,000 Net Income 42,000 − 3,000 45,000 Sales Use the incremental approach to determine if Product B should be dropped. Solution By dropping Product B, the company will lose the sale revenue from the product line. The company will also obtain gains in the form of avoided costs. But it can avoid only the variable costs and direct fixed costs of product B and not the allocated fixed costs. Hence: If Product B is Dropped Gains: Variable Costs Avoided GH¢169,000 Direct Fixed Costs Avoided GH¢86,000 255,000 Less: Sales Revenue Lost 314,000 Decrease in Net Income of the Company 59,000 Illustration 2 B & B Inc., a retailing company has two departments, X and Y. A recent monthly contribution format income state for the company follows. X (GH¢) Y (GH¢) Total(GH¢) Sales 3,000,000 1,000,000 4,000,000 Variable expenses 900,000 400,000 1,300,000 Contribution margin 2,100,000 600,000 2,700,000 Fixed expenses 1,400,000 800,000 2,200,000 Operating income(loss) 700,000 -200,000 500,000 A study indicates that GH¢340,000 of the fixed expenses being charged to Y are sunk costs or allocated costs that will continue even if Y is dropped. In addition the elimination of Y will result in a 10% decrease in the sales of X. Required: If Department Y is discontinued, will this be a positive move or a negative move for the company as a whole? Solution Contribution margin lost if Y is dropped: (GH¢) Department Y contribution margin lost -600,000 Department X contribution margin lost -210,000 Total contribution margin lost -810,000 Avoidable fixed costs 460,000 Decrease in operating income -350,000 1.3.6 Analyse Decision with Multiple Product and Limited Resources Managers frequently confront the short-run problem of making the best use of scarce resources that are essential to production activity or service provision but have limited availability. Scarce resources include machine hours, skilled labour hours, raw materials, production capacity, and Other inputs. Whenever demand exceeds productive capacity, a production constraint (bottleneck) exists. This means that the company is unable to fill all orders and some choices have to be made concerning which orders are filled and which are not filled. Determining the best use of a scarce resource requires management to identify company objectives. If an objective is to maximize company profits, a scarce resource is best used to produce and sell the product generating the highest contribution margin per unit of the scarce resource. This strategy assumes that the company must ration only one scarce resource. Total contribution margin will be maximized by promoting those products or accepting those orders that provide the highest unit contribution margin in relation to the constrained resource. Single Limiting Factor Where a limiting factor exists, instead of concentrating on those products, which maximise contribution, we do the following; (a) Contribution will be maximised by earning the biggest possible contribution per unit of scarce resource. Thus if Grade A labour is the limiting factor, contribution will be maximised by earning the biggest contribution per hour of Grade A labour worked. Similarly, if machine time is in short supply, profit will be maximised by earning the biggest contribution per machine hour worked. (b) The limiting factor decision therefore involves the determination of the contribution earned by each different product per unit of scarce resource. Steps Step 1: Identify the scarce resource (limiting factor) Step 2: Calculate the amount of the limiting factor needed by each product. Step 3: Confirm that the amount of the limiting factor is insufficient to allow all products to be produced. Step 4: Calculate the contribution earned per unit of each product. Step 5: Calculate the contribution of each product per unit of the limiting factor by dividing step 4 by step 2 Step 6: Establish production priority by ranking products according to the contribution per unit of the scarce resource. Step 7: Allocate the available scarce resource according to the ranking. Illustration A company manufactures three products (X, Y and Z). All direct operatives are the same grade and are paid at GH¢11 per hour. It is anticipated that there will be a shortage of direct operatives in the following period, which will prevent the company from achieving the following sales targets: Product X 3,600 units Product Y 8,000 units Product Z 5,700 units Selling prices and costs are shown below Product X, Y, and Z Selling Prices and Costs per unit Product X Product Y Product Z 100.00 69.00 85.00 Production* 51.60 35.00 42.40 Non-Production 5.00 3.95 4.25 Production 27.20 19.80 21.00 Non-Production 7.10 5.90 6.20 * includes the cost of direct operatives 24.20 16.50 17.60 Selling prices Variable cost: Fixed Costs: The fixed costs per unit are based on achieving the sales targets. There would not be any savings in fixed costs if production and sales are at a lower level Solution Step 1: Limiting factor if shortage of direct operatives Step 2: Calculate the amount of the limiting factor needed by each product. Product X GH¢24.20/unit ÷ GH¢11/hr = 2.2 hrs per unit × 3,600 units = 7,920 hrs Product Y GH¢16.50/unit ÷ GH¢11/hr = 1.5 hrs per unit × 8,000 units = 12,000 hrs Product Z GH¢17.60/unit ÷ GH¢11/hr = 1.6 hrs per unit × 5,700 units = 9,120 hrs Total hours needed = 29,040 hrs Step 3: Confirm that the amount of the limiting factor is insufficient to allow all products to be produced. Direct labour hours available are 2,640 less (26,400 - 29,040) than those required to achieve the sales targets. Step 4: Calculate the contribution earned per unit of each product. Contribution is sales revenue less variable costs (both production and non-production). Thus: Product X GH¢100.00 - GH¢56.60 (51.60 + 5.00) = GH¢43.40 per unit Product Y GH¢69.00 - GH¢38.95 (35.00 + 3.95) = GH¢30.05 per unit Product Z GH¢85.00 - GH¢46.65 (42.40 + 4.25) = GH¢38.35 per unit Step 5: Calculate the contribution of each product per unit of the limiting factor by dividing step 4 by step 2 The contribution per unit of scarce resource can be calculated either as a GH¢ contribution per hour of direct operative time or as a GH¢ contribution per GH¢ cost of direct operatives. Thus: Product X GH¢43.40/unit ÷ 2.2 hrs/unit = GH¢19.73 per direct operative hour Product Y GH¢30.05/unit ÷ 1.5 hrs/unit = GH¢20.03 per direct operative hour Product Z GH¢38.35/unit ÷ 1.6 hrs/unit = GH¢23.97 per direct operative hour Or Product X GH¢43.40/unit ÷ GH¢24.20/unit = GH¢1.793 per GH¢ cost of direct operatives Product Y GH¢30.05/unit ÷ GH¢16.50/unit = GH¢1.821 per GH¢ cost of direct operatives Product Z GH¢38.35/unit ÷ GH¢17.60/unit = GH¢2.179 per GH¢ cost of direct operatives Step 6: Establish production priority by ranking products according to the contribution per unit of the scarce resource. On the basis of the contribution per unit of the scarce resource, Product Z would be manufactured as the first priority (GH¢23.97/hr or GH¢2.179/GH¢ cost), followed by Product Y (GH¢20.03/hr or GH¢1.821/GH¢ cost) and finally Product X (GH¢19.73/hr or GH¢1.793/GH¢ cost). The same conclusion would be reached whichever of the calculations in stage 4 was used because the basis is the same. Step 7: Allocate the available scarce resource according to the ranking. The scarce resource of direct operative hours needs to be allocated according to the production priority established in stage 5 above. Product Z has first priority and so the direct operative hours will be allocated up to the limit required to achieve the sales target of 5,700 units. This was calculated in stage 1 to be 9,120 hours. The next priority is Product Y. The allocation of the 26,400 hours available can be set out as follows: Product Z= 9,120 hours 5,700 units Product Y =12,000 hours 8,000 units 21,120 hours Product X = 5,280 hours 2,400 units (26,400 - 21,120) (5,280 hours ÷ 2.2 hours/unit) 26,400 hours Multiple Limiting Factors-Linear Programming When the production process requires two or more production constraints, the choice of sales mix involves a more complex analysis, and in contrast to the case of one production constraint which solves for a single product, the solution can include both products when two constraints are involved. When there are more than one limiting factor, then a technique known as linear programming is used. In formulating a linear programming problem the steps involved are as follows; Define the unknowns, i.e. the variables that need to be determined Formulate the constraints, i.e. the limitation that must be placed on the variables Formulate the objective function that needs to be maximised or minimised Graph the constraints and objective functions Determine the optimal solution to the problem by reading the graph. Note that non-negativity constraints will be needed to ensure that there are no negative values. Linear programming problems could also be solved using algebra Illustration 1 John manufactures chairs and tables. Each product passes through a cutting process and an assembling process. One chair makes a contribution of GH¢50 and take 6 hours cutting time and 4 hours assembly time. One table makes a contribution of GH¢40 and takes 3 hours cutting time and 8 hours assembly time. There is a maximum of 36 cutting hours available each week and 48 assembly hours. Find the output that maximises contribution. Solution Let x = number of chairs produced each week and y= number of tables produced each week. Constraints are: 6x+3y = 36 4x+8y = 48 Solving for x and y simultaneously, x = 4 and y = 4 Thus maximum contribution = (4 * 50 ) + (4*40) = GH¢360 1.4 Behavioural, Implementation and Issues in Decision Making A well-known problem in business today is the tendency of managers to focus on short-term goals and neglect the long-term strategic goals because their compensation is based on short term accounting measures such as net income. Many critics of relevant cost analysis have raised this issue. As noted, it is critical that the relevant cost analysis be supplemented by a careful consideration of the firm’s long-term, strategic goals. Without strategic considerations, management could improperly use relevant cost analysis to achieve a shortterm benefit and potentially suffer a significant long-term loss. For example, a firm might choose to accept a special order because of a positive relevant cost analysis without properly considering that the nature of the special order could have a significant negative impact on the firm’s image in the marketplace and perhaps a negative effect on sales of the firm’s other products. The important message for managers is to keep the strategic objectives in the forefront in any decision situation. Further, people are affected by decisions. The people may be customers, or buyers for corporate customers. They may also be suppliers. However, employees will be most affected by decisions that a company takes. The decision would mean more overtime, redundancy or changed work procedures. They have to be paid and then they are no longer employees. This affects morale of the remaining employees. The morale of the employees affects the productivity of the shop floor, the reject rate and the rate of labour turnover. Trade union organisations may consider sending the company to court is the decision is to render some staff members redundant. This might dent the image of the company which could be translated into low demand for goods produced. Some customers regard certain goods as jointly demanded and so its withdrawal will lead to the reduction in demand for the other product. For instance, if the production of saucers is withdrawn, the demand for tea cups will reduce. 1.5 Cost-Volume-Profit (CVP) Analysis In any business, or, indeed, in life in general, hindsight is a beautiful thing. If only we could look into a crystal ball and find out exactly how many customers were going to buy our product, we would be able to make perfect business decisions and maximise profits. One of the most important decisions that needs to be made before any business even starts is ‘how much do we need to sell in order to break even?’ By ‘break even’ we mean simply covering all our costs without making a profit. CVP analysis is designed to illustrate the effects of changes in volume or output of work done or sales made upon sales revenue and costs. As a consequence the effect upon profit is shown as the difference between total revenue and total costs. CVP analysis looks primarily at the effects of differing levels of activity on the financial results of a business. In performing this analysis, there are several assumptions made, including: Sales price per unit is constant. Variable costs per unit are constant. Total fixed costs are constant. Everything produced is sold. Costs are only affected because activity changes. If a company sells more than one product, they are sold in the same mix. The time scale necessary to implement any decision based upon the analysis is relatively short. Cost and revenue are linear The contribution relationships are valid and constant Either one product is made or a combination is made in the same proportion throughout. All costs behave in the manner assumed and can be split into fixed or variable. Useful relationships 1. Profit = Revenue- Costs 2. Total Cost= Variable costs- Fixed costs 3. Profit = (Revenue – Variable costs)- Fixed costs 4. Contribution= Revenue – Variable costs 5. Total contribution = Quantity of sales * Contribution per unit 6. At Break-Even: Revenue =Total Costs 7. At Break-Even: Total contribution = Fixed costs and 8. Break-Even quantity = Fixed costs/Contribution per unit Contribution margin and contribution margin ratio Key calculations when using CVP analysis are the contribution margin and the contribution margin ratio. The contribution margin represents the amount of income or profit the company made before deducting its fixed costs. Said another way, it is the amount of sales dollars available to cover (or contribute to) fixed costs. When calculated as a ratio, it is the percent of sales dollars available to cover fixed costs. Once fixed costs are covered, the next dollar of sales results in the company having income. The contribution margin is sales revenue minus all variable costs. It may be calculated using dollars or on a per unit basis. If The Three M's, Inc., has sales of GH¢750,000 and total variable costs of GH¢450,000, its contribution margin is GH¢300,000. Assuming the company sold 250,000 units during the year, the per unit sales price is GH¢3 and the total variable cost per unit is GH¢1.80. The contribution margin per unit is GH¢1.20. The contribution margin ratio is 40%. It can be calculated using either the contribution margin in dollars or the contribution margin per unit. To calculate the contribution margin ratio, the contribution margin is divided by the sales or revenues amount. Contribution Margin GH¢ 750,000 450,000 300,000 Sales Variable Costs 𝐶𝑜𝑛𝑡𝑟𝑖𝑏𝑢𝑡𝑖𝑜𝑛 𝑚𝑎𝑟𝑔𝑖𝑛 𝑟𝑎𝑡𝑖𝑜 = 𝐶𝑜𝑛𝑡𝑟𝑖𝑏𝑢𝑡𝑖𝑜𝑛 𝑚𝑎𝑟𝑔𝑖𝑛 𝑆𝑎𝑙𝑒𝑠 = 300,000 750,000 40% 𝑜𝑟 Per Unit (GH¢) 3 1.8 1.2 1.2 3 = 40% Break-even point The break-even point represents the level of sales where net income equals zero. In other words, the point where sales revenue equals total variable costs plus total fixed costs, and total contribution margin equals fixed costs. 𝐼𝑛 𝑡𝑒𝑟𝑚𝑠 𝑜𝑓 𝑠𝑎𝑙𝑒𝑠 𝑢𝑛𝑖𝑡𝑠 (𝑏𝑟𝑒𝑎𝑘 − 𝑒𝑣𝑒𝑛 𝑝𝑜𝑖𝑛𝑡 𝑖𝑛 𝑢𝑛𝑖𝑡𝑠) = 𝐹𝑖𝑥𝑒𝑑 𝑐𝑜𝑠𝑡 𝐶𝑜𝑛𝑡𝑟𝑖𝑏𝑢𝑡𝑖𝑜𝑛 𝑝𝑒𝑟 𝑢𝑛𝑖𝑡 𝐼𝑛 𝑡𝑒𝑟𝑚𝑠 𝑜𝑓 𝑠𝑎𝑙𝑒𝑠 𝑟𝑒𝑣𝑒𝑛𝑢𝑒 (𝑏𝑟𝑒𝑎𝑘 − 𝑒𝑣𝑒𝑛 𝑝𝑜𝑖𝑛𝑡 𝑖𝑛 𝑠𝑎𝑙𝑒𝑠) = 𝐹𝑖𝑥𝑒𝑑 𝑐𝑜𝑠𝑡 𝐶𝑜𝑛𝑡𝑟𝑖𝑏𝑢𝑡𝑖𝑜𝑛 𝑟𝑎𝑡𝑖𝑜 Using the previous information and given that the company has fixed costs of GH¢300,000. Break-even point in dollars: The break-even point in sales dollars of GH¢750,000 is calculated by dividing total fixed costs of $300,000 by the contribution margin ratio of 40%. 𝐼𝑛 𝑡𝑒𝑟𝑚𝑠 𝑜𝑓 𝑠𝑎𝑙𝑒𝑠 𝑟𝑒𝑣𝑒𝑛𝑢𝑒 (𝑏𝑟𝑒𝑎𝑘 − 𝑒𝑣𝑒𝑛 𝑝𝑜𝑖𝑛𝑡 𝑖𝑛 𝑠𝑎𝑙𝑒𝑠) = 300,000 0.4 = GH¢750,000 Break-even point in units: The break-even point in units of 250,000 is calculated by dividing fixed costs of GH¢300,000 by contribution margin per unit of GH¢1.20. 𝐼𝑛 𝑡𝑒𝑟𝑚𝑠 𝑜𝑓 𝑠𝑎𝑙𝑒𝑠 𝑢𝑛𝑖𝑡𝑠 (𝑏𝑟𝑒𝑎𝑘 − 𝑒𝑣𝑒𝑛 𝑝𝑜𝑖𝑛𝑡 𝑖𝑛 𝑢𝑛𝑖𝑡𝑠) 300,000 = 250,000 𝑢𝑛𝑖𝑡𝑠 1.2 Targeted income CVP analysis is also used when a company is trying to determine what level of sales is necessary to reach a specific level of income, also called targeted income. To calculate the required sales level, the targeted income is added to fixed costs, and the total is divided by the contribution margin ratio to determine required sales dollars, or the total is divided by contribution margin per unit to determine the required sales level in units. 𝑅𝑒𝑞𝑢𝑖𝑟𝑒𝑑 𝑠𝑎𝑙𝑒𝑠 𝑖𝑛 GH¢ = Fixed Cost + Targeted Income Contribuion margin ratio 𝑅𝑒𝑞𝑢𝑖𝑟𝑒𝑑 𝑠𝑎𝑙𝑒𝑠 𝑖𝑛 units = Fixed Cost + Targeted Income Contribuion margin per unit Using the data from the previous example, what level of sales would be required if the company wanted GH¢ 60,000 of income? The GH¢60,000 required is called the targeted income. The required sales level is GH¢900,000 and the required number of units is 300,000. Remember that there are additional variable costs incurred every time an additional unit is sold, and these costs reduce the extra revenues when calculating income. 𝑅𝑒𝑞𝑢𝑖𝑟𝑒𝑑 𝑠𝑎𝑙𝑒𝑠 𝑖𝑛 GH¢ = 300,000 + 60,000 = GH¢900,000 0.4 𝑅𝑒𝑞𝑢𝑖𝑟𝑒𝑑 𝑠𝑎𝑙𝑒𝑠 𝑖𝑛 units = 300,000 + 60,000 = 300,000 units 1.2 Note that this calculation of targeted income assumes it is being calculated for a division as it ignores income taxes. If a targeted net income (income after taxes) is being calculated, then income taxes would also be added to fixed costs along with targeted net income. Margin of Safety This is the amount by which the sales in units or a percentage of budgeted sales can fall below before a loss is made. 𝑀𝑎𝑟𝑔𝑖𝑛 𝑜𝑓 𝑠𝑎𝑓𝑒𝑡𝑦 𝑖𝑛 units = Budgeted sales − Break − even sales 𝑀𝑎𝑟𝑔𝑖𝑛 𝑜𝑓 𝑠𝑎𝑓𝑒𝑡𝑦 𝑎𝑠 𝑎 % 𝑜𝑓 𝑠𝑎𝑙𝑒𝑠 = Budgeted sales − Break − even sales ∗ 100% = Budgeted sales Using the data from the above example with additional information of budgeted sales for the period of 350,000 units, calculate the margin of safety in units and calculate the margin of safety as a % of budgeted sales. 𝑀𝑎𝑟𝑔𝑖𝑛 𝑜𝑓 𝑠𝑎𝑓𝑒𝑡𝑦 𝑖𝑛 units = 350,000 − 250,000 = 100,000 units 𝑀𝑎𝑟𝑔𝑖𝑛 𝑜𝑓 𝑠𝑎𝑓𝑒𝑡𝑦 𝑎𝑠 𝑎 % 𝑜𝑓 𝑠𝑎𝑙𝑒𝑠 = 350,000 − 250,000 ∗ 100% = 40% 250,000 Sensitivity Analysis A business environment can change quickly, so a business should understand how sensitive its sales, costs, and income are to changes. Sensitivity analysis is a “what if” technique that managers use to examine how an outcome will change if the original predicted data are not achieved or if an underlying assumption changes. In the context of CVP analysis, sensitivity analysis examines how operating income (or the breakeven point) changes if the predicted data for selling price, variable cost per unit, fixed costs, or units sold are not achieved. The sensitivity to various possible outcomes broadens managers’ perspectives as to what might actually occur before they make cost commitments. CVP analysis using the break-even formula is often used for this analysis. For example, marketing suggests a higher quality product would allow The Three M’s Inc, to raise its selling price 10%, from GH¢ 3.00 to GH¢ 3.30. To increase the quality would increase variable costs to GH¢ 2.00 per unit and fixed costs to GH¢ 350,000. If The Three M's, Inc., followed this scenario, its break-even in units would be 269,231. 𝐵𝑟𝑒𝑎𝑘 − 𝑒𝑣𝑒𝑛 𝑠𝑎𝑙𝑒𝑠 𝑢𝑛𝑖𝑡𝑠 = 𝐹𝑖𝑥𝑒𝑑 𝑐𝑜𝑠𝑡 350,000 = = 269,231 𝑢𝑛𝑖𝑡𝑠 𝐶𝑜𝑛𝑡𝑟𝑖𝑏𝑢𝑡𝑖𝑜𝑛 𝑝𝑒𝑟 𝑢𝑛𝑖𝑡 (3.30 − 2) These changes in variable costs and sales result in a higher break-even point in units than the 250,000 break-even units calculated with the original assumptions. The critical question is, “Will the customers continue to purchase, and are new or existing customers identified that will purchase the additional 19,231 units of the product required to break even at the higher sales price?” CVP with Multiple Product Mix In cases where a company deals in multiple products, the analysis is similar to the single product in that the concepts and formulae remain the unchanged. The only modification however is that the analysis is performed by using weighted averages components. For example, instead of contribution, weighted contribution margins and selling prices are used. Limitation of CVP Analysis 1. Profits are calculated on a variable cost basis or, if absorption costing is used, it is assumed that production volumes are equal to sales volumes. 2. Fixed costs remain constant over the ‘relevant range’ – levels of activity in which the business has experience and can therefore perform a degree of accurate analysis. It will either have operated at those activity levels before or studied them carefully so that it can, for example, make accurate predictions of fixed costs in that range. 3. Costs can be divided into a component that is fixed and a component that is variable. In reality, some costs may be semi-fixed, such as telephone charges, whereby there may be a fixed monthly rental charge and a variable charge for calls made. 4. The total cost and total revenue functions are linear. This is only likely to hold true within a short-run, restricted level of activity. 5. All other variables, apart from volume, remain constant, ie volume is the only factor that causes revenues and costs to change. In reality, this assumption may not hold true as, for example, economies of scale may be achieved as volumes increase. Similarly, if there is a change in sales mix, revenues will change. Furthermore, it is often found that if sales volumes are to increase, sales price must fall. These are only a few reasons why the assumption may not hold true; there are many others. Illustration 1 Ababio Plastic Company produces plastic buckets which are distributed all over the country. During the years 2009 and 2010, the following data were extracted: Sales (GHC) Profits (GHC) Year 2009 1,200,000 80,000 Year 2010 1,400,000 130,000 You are required to calculate the following: i. Profit –Volume Ratio (P/V Ratio) ii. Break – Even Point in Sales value iii. Profit when the sales value is GHC1,800,000 iv. The Sales Value required to make a profit of GHC120,000 v. The Margin of Safety in the Year 2010 Solution Year 2009 Year 2010 Difference (i) P/V Ratio = 50,000 x 100 200,000 Less Profit Fixed Cost (iii) (iv) (v) Profit (GHC) 1,200,000 1,400,000 200,000 80,000 130,000 50,000 = 25% Contribution in 2009 (1,200,000 x 25%) (ii) Sales (GHC) Break-even point in sales value: Fixed Cost = 220,000 P/V Ratio 25% 300,000 80,000 220,000 = GHC880,000 Profit when sales is GHC1,800,000: Contribution (GHC1,800,000 x 25%) GHC 450,000 Less Fixed Cost 220,000 Profit 230,000 Sales to earn a profit of GHC120,000: Fixed Cost + Target Profit = P/V Ratio = Margin of safety in 2010: Actual sales - Break-en sales 1,400,000 - 880,000 = 220,000 + 120,000 25% GHC1,360,000 GHC520,000 Practice Questions 1. Dolow produces computer component A for sale at GH¢47 per unit to a Manufacturer of computers. The company currently produces 15,000 units of the component per annum. Total cost of production and unit cost are as follows: Production Cost (GH¢) Unit Cost (GH¢) Direct Materials 210,000 14 Direct labour 180,000 12 Variable production cost 30,000 2 Fixed manufacturing overhead 150,000 10 Share of non-production overhead 105,000 7 675,000 45 A supplier has offered to supply 15,000 units of the components per annum at a price of GH¢39 per unit over a four-year period without any change in price. If Dolow accepts the offer, the following are the effects on current operation. (1) Direct labour will be redundant but at a redundancy cost of GH¢5,000. (2) Direct materials and variable production cost will be avoidable (3) Fixed manufacturing cost will be reduced by GH¢18,750 per annum (4) Share of non-production overhead cost will stay as it is. Assuming further that, the extra capacity for accepting the contract offer from the supplier can be used to produce and sell 15,000 units of component Z at a price of GH¢43 per unit with the following assumptions: (1) All of the labour force required to manufacture component A will be used to make component Z. (2) Variable manufacturing overhead will remain same. (3) The fixed manufacturing overhead will remain same. (4) Non-manufacturing overhead will be the same. (5) The materials for component A will not be needed but additional materials at a cost of GH¢15 per unit will be required for production. Required: (a) Should Dolow make or buy component A? (b) Should Dolow accept the offer and use the available space to manufacture component Z? 2. Xexe Ltd produces 4 products and is planning its production mix for the next period. Estimated cost, sales and production data are shown below: A B C D Selling price/unit (GH¢) 50 70 80 100 Materials @GH¢4/kg 12 36 20 24 Direct labour@GH¢2/hr 6 4 14 10 Maximum demand( units) 3000 3000 3000 3000 Required: (i) Assuming labour hours is a limiting factor in the period, advise management on the most appropriate mix if labour hours is limited to 45,000 hours. (ii) Assuming, materials is a limiting factor in the period, advise management on the most appropriate mix if materials is limited to 55,000 kgs in the period. 3. A Sports Kit manufacturer, in conjunction with a Software house, is considering the launch of a new sporting simulator based on video-tapes that enables greater realism to be achieved. Two proposals are being considered. Both use the same production facilities and, as these are limited, only one product can be launched. The following data are the best estimates the firm has been able to obtain: Football Simulator Cricket Simulator Annual volume (units) 40,000 30,000 Selling price (per unit) GH¢65 GH¢100 Variable cost of production GH¢40 GH¢50 Fixed production cost GH¢300,000 GH¢300,000 Fixed selling and administrative cost GH¢225,000 GH¢675,000 The higher selling and administrative costs for the cricket simulator reflect the additional advertising and promotion costs expected to be necessary to sell the more expensive cricket system. The firm has a minimum target of GH¢100,000 profit per year for new products. The management recognizes the uncertainty in the above estimates and wishes to explore the sensitivity of the profit on each product to changes in the values of the variables (volume, price, variable cost per unit and fixed costs). You are required to calculate for each of the products: (a) The expected profit from each product (b) (i) The units to be produced if the targeted profit is GH¢100,000 (ii) The unit selling price per product, if the expected profit per year is GH¢100,000