Some List of sewing occupations final

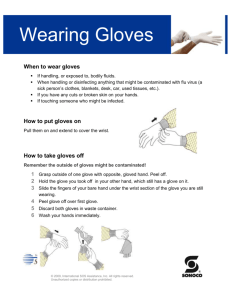

advertisement