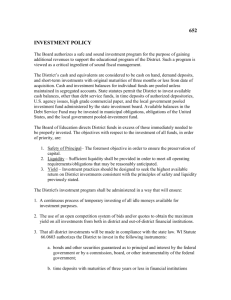

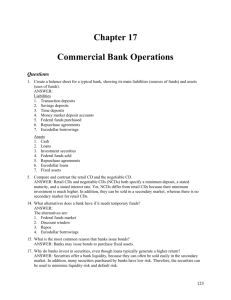

Capital

advertisement