Weeks 1 and 2: Historical Background

advertisement

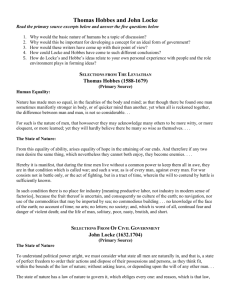

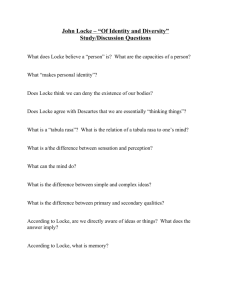

General Philosophy Dr Peter Millican, Hertford College Lectures 1 and 2: Historical Background What is “General Philosophy”? Some central issues of epistemology (“What can we know?”) and metaphysics (“What is the nature of things?”). Illustrates how philosophy is done: types of arguments, methods of enquiry etc. Historical focus: all but one of the topics (Knowledge) are introduced through the writings of “Classical” philosophers of the 17th and 18th centuries. 2 Why Study Philosophy Historically? How the agenda got set: when and why did these problems become important? Learning the labels: “Cartesian dualism”, “Lockean veil of perception”, “Berkeleian idealism”, “Berkeleian instrumentalism”, “Humean compatibilism”, “Cartesian” or “Humean” scepticism etc. Great original thinkers, writing for a general audience: so their ideas are profound, and they don’t take too much for granted. 3 The Value of Historical Perspective 4 Philosophical ideas tend to have broad and deep interconnections. Studying classic “battles of ideas” enables us to view these interconnections in context and with the perspective of history. Many classic themes recur throughout the history of thought, sometimes hidden under the surface of contemporary debate. Ignoring the past can make us slaves of fashion, and blinker us to other options. The Topics (1) Scepticism: Descartes’ evil genius, Locke’s veil of perception Knowledge: Responding to scepticism Perception: Locke’s representative theory of perception, Berkeley’s criticisms Primary and secondary qualities: Boyle and Locke’s theory, Berkeley’s criticisms Induction: Hume’s sceptical argument, and his denial that nature is “intelligible” 5 The Topics (2) Free Will: Hobbes’ and Hume’s compatibilism, and their naturalistic view of man as part of nature Mind and Body: Descartes’ dualism, various philosophers on the limited powers of matter and their religious implications Personal Identity: Locke’s attempt to ground this independently of “spiritual substance” 6 The Birth of Philosophy The ancient Greeks, distinctively, aimed for rational understanding independent of religious tradition. Many different philosophers and “schools”: – Various “Pre-Socratics” (c. 600 - 400 BC) – Plato and his Academy (387 BC -) – Aristotle (pictured) and his Lyceum (335 BC -) – Pyrrhonian sceptics (c. 320 BC -) – Epicureans (c. 307 BC -) – Stoics (c. 300 BC -) 7 The Institution of Scholasticism Roman Empire became Christianised: – Pagan temples and libraries destroyed 391 AD; – Non-Christian “schools” closed down 529 AD. Plato and Aristotle adopted: – Christian Platonism (e.g. Augustine 354-430) – Christian Aristotelianism (e.g. Aquinas 1225-74) The Christian Aristotelian worldview became dominant in the medieval monastic schools, hence “Scholasticism”. 8 Fixed Stars Saturn Jupiter Mars Sun Venus Mercury Moon Fire Air Water & Earth 9 4 Aristotle’s Universe Rediscovery of the Classics Ancient texts survived in the Byzantine Empire, or in the Arabic world. – Manuscripts brought West in flight from Ottoman Turks (Constantinople fell 1453), fostered the development of Humanism in Renaissance Italy. Printing (invented 1450) gave them much wider circulation, e.g.: – Lucretius (rediscovered 1417, printed 1486) – Sextus Empiricus (translated into Latin 1562) 10 Upheaval and Instability Many factors contributed to Western instability in the period 1500-1650, e.g.: – growth of population and trade; – discovery of the New World (America etc.); – consequent economic disruption; – realisation that ancient maps etc. were wrong; – suggestions of cultural relativity; – technology of gunpowder and consequent centralisation of power. 11 The Hereford “Mappa Mundi” (c. 1290) based on the writings of Orosius, a pupil of Saint Augustine, part of a compendium of knowledge to refute the pagans 12 The Reformation The Reformation added to this crisis: – Luther rebelled against the Church of Rome, starting in 1517; – Many parts of Europe (especially in the North) became Protestant; – Savage wars throughout Europe arising from religious differences (e.g. Thirty Years’ War 1618-48, English Civil War 1639-51); – Peace “of exhaustion” at Westphalia, 1648 led to greater religious toleration. 13 The Problem of the Criterion A sceptical problem raised by Sextus Empiricus in his Outlines of Pyrrhonism: How can any criterion of reliable knowledge be chosen, unless we already have some reliable criterion for making that choice? – Roman Catholics appeal to tradition (Church, Bible, Aristotle); Protestants appeal to the believer’s personal response to the Bible; – How to know who is right? (Maybe neither?!) 14 Aristotelian Science Elements and Natural Motions – Four elements: fire, air, water, and earth. – Fire/air naturally move upwards, water/earth downwards, each seeking its natural place. – Heavier things fall faster, in proportion to weight. (Physics, IV 8) A Teleological Physics – Strivings, horror of a vacuum etc. – Everything strives towards the eternal, hence heavenly bodies move in circles, and must be made of a fifth element, aether. 15 Intelligibility, or Empty “Explanation”? “Why does water rise up a siphon pipe?” “Because Nature abhors a vacuum.” “Why does opium make one sleep?” “Because it contains a dormitive virtue, whose nature is to make the senses soporific.” Molière (1673) 16 Galileo’s Experiments Aristotle couldn’t explain: – the flight of a cannonball; – a sledge sliding on flat ice; – water dripping from a gutter. Galileo was reported (by Viviani) to have performed another critical experiment: – dropping a large and a small ball together from the Leaning Tower of Pisa. Contrary to Aristotle, they fell at similar speeds. 17 Galileo’s Telescope The telescope was invented in Holland in 1608, and Galileo made his own in 1609. What he saw with it refuted Aristotle’s cosmology: – Mountains and valleys on the moon; – Four moons orbiting around Jupiter; – Innumerable stars too dim for the naked eye; – Phases of Venus, sometimes “full” (implying that it is then on the opposite side of the Sun). 18 Venus as considered by Ptolemy Sun Venus Earth 14 From Final to Efficient Causes Aristotelian science was based on purposes, or “final” causation: – Things strive to reach their natural place, or to avoid abhorrent situations (e.g. a vacuum); Galileo preferred “efficient” causation: – The outcome depends on where the causal sequence happens to lead. – Matter doesn’t strive; it is inert, remaining in its state of motion or rest unless acted on. 20 The “Mechanical Philosophy” The paradigm of efficient causation is via mechanical contact: – Interaction between contiguous particles of matter by pressure and impact. Compared with pseudo-explanations involving “occult” qualities (horror of a vacuum, dormitive virtue etc.), this seems: – genuinely explanatory; – genuinely intelligible. 21 Inertia and the Orbiting Heavens Thus Galileo claimed, against Aristotle: – Matter does not “strive”. – Left to itself matter is “inert”: it continues in a uniform state of rest or motion until acted upon by a force (e.g. pushed along). – The heavenly bodies are not composed of a special “aether”, but of ordinary matter, and therefore subject to the same laws. BUT: why then does the Moon orbit the Earth, and the planets orbit the Sun? 22 The Father of Modern Philosophy Attacks Aristotelian tradition using the sceptical problem of the criterion; Builds on Galileo’s mechanical philosophy grounding it on a theory of matter’s “essence”; Makes room for mind 23 as an “essence” radically distinct from matter (thus effectively removing it from physical science). Descartes – Epistemology Seeks reliable anti-sceptical basis for knowledge, not appealing to authority: – “I think therefore I am”, provides a first example of something known, and reveals what is needed: clear and distinct perception. – Then prove clearly and distinctly that the idea of God implies a perfect cause: i.e. God. – A perfect God cannot deceive, so our faculties must be reliable if used properly. – Hence the importance of Descartes’ Method. 24 Descartes – Science Descartes was a major natural philosopher: – First to explain the rainbow in detail; – Discovered co-ordinate geometry; – Suggested circulation of the blood; – Concluded that the Earth orbits the Sun. His most important intellectual legacy: The ideal of a mechanistic science of the world, based on the simple mathematical properties of extended matter. 25 Descartes and Essences The real qualities of matter follow from its essence, simple geometrical extension. – This essence, known through God-given innate ideas, implies mathematical laws of motion. – Bodies are passive, remaining in the same state (inertia) until a force is applied. – Qualities perceived by the senses (Locke’s “secondary qualities”) are observer-dependent. Mind is a distinct, active immaterial substance, whose essence is thinking. 26 Descartes’ Physics Since matter’s essence is extension, nonmaterial extension is impossible. Thus: – The physical world is a plenum (no vacuum); – All motion must take the form of circuits of matter within the plenum. – This can be expected to give rise to vortices, circular motions like whirlpools. – A vortex can explain why the planets orbit the Sun without shooting off under inertia. 27 The Monster of Malmesbury (and Magdalen Hall = Hertford College!) Hobbes denies – immaterial substance; – witchcraft; – reliance on revelation. Hobbes asserts – universal determinism; – obedience to sovereign in religion and morals. 28 Hobbes’ Leviathan (1651) In the state of nature, the life of man is ‘solitary, poore, nasty, brutish and short’. The only solution is absolute sovereignty. 29 Hobbes’ Materialism Hobbes, like Descartes, is a plenist, but he recognises only material substance, and does so on logical grounds: “When men make a name of two Names, whose significations are contradictory and inconsistent”, the result is “but insignificant sounds”, “as this name, an incorporeall body, or (which is all one) an incorporeall substance”. Leviathan ch. 4 So Descartes’ supposed mental “immaterial substance” is a contradiction in terms! 30 Hobbes’ Compatibilism Hobbes is the first classic compatibilist, who takes determinism (i.e. all that happens is completely determined by causal laws) to be fully compatible with genuine free will. “LIBERTY, or FREEDOME, signifieth (properly) the absence of Opposition (by Opposition, I mean externall Impediments of motion;) … A FREEMAN, is he, that in those things, which by his strength and wit he is able to do, is not hindred to doe what he has a will to.” 31 Leviathan ch. 21 Materialism and Atheism Hence for Hobbes, all that exists is material, even God, and everything is determined. Many took Hobbes to be an atheist. – In 1666 Parliament cited his “atheism” as probable cause of the plague and fire of London! – His “Pernicious” books were publicly burned in Oxford in 1683, because of their “Damnable Doctrines … false, seditious, and impious, and most of them … also Heretical and Blasphemous … and destructive of all Government”. 32 The Evils of “Hobbism” In 1668, Daniel Scargill of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge was expelled. In his public recantation, he confessed: “I have lately vented and publickly asserted … divers wicked, blasphemous, and Atheistical positions … professing that I gloried to be an Hobbist and an Atheist … Agreeably unto which principles I have lived in great licentiousness, swearing rashly, drinking intemperately … corrupting others …” 33 Opposing Materialism The main argument against Hobbist materialism was to insist on the limited powers of “brute matter”, which: – is necessarily passive or inert (as demonstrated by the phenomenon of inertia); – in particular, cannot possibly give rise to mental activity such as perception or thought. This point was pressed by Ward (1656), More (1659), Stillingfleet (1662), Tenison (1670), Cudworth (1678), Glanvill (1682), Locke (1690). 34 Boyle’s Corpuscularianism Though Hobbist materialism was anathema, physical mechanism thrived in England: – Robert Boyle, with an interest in chemistry and based in Oxford, speculated that material substances are composed of imperceptible “corpuscles” made of “universal matter”. His term “corpuscularianism” conveniently avoided the atheistic associations of ancient “atomism” 35 Atoms and the Void Boyle’s universal matter is both extended and impenetrable, so unlike Descartes he can draw a distinction between: – impenetrable extension (i.e. matter) – penetrable extension (i.e. empty space) He retains Descartes’ primary-secondary quality distinction: observable “secondary” qualities of substances flow from how the corpuscles are physically arranged. 36 Meanwhile, in the Heavens … In 1627 Johannes Kepler published tables enabling the calculation of planetary positions to an accuracy which turned out to be over 1000 times better than any previous method. Kepler’s method is based on the hypothesis that each planet moves in an ellipse around the Sun (which is at one “focus” of the ellipse). The method’s sheer accuracy led over time to general acceptance of that hypothesis. 37 Newtonian Physics Isaac Newton took Descartes’ concept of inertia, and Boyle’s theory of “atoms and the void”, but postulated a force of gravity acting through it. – If gravity acts in inverse proportion to the square of the distance between two objects, and bodies accelerate in proportion to the total force acting on them, then the elliptical motion of the planets around the Sun can be elegantly explained. 38 Refuting Aristotle and Descartes Newton’s theory could also predict – using the very same equations – the motion of cannonballs etc. on Earth. – Another nail in the coffin of the Aristotelian supposition that heavenly bodies act differently. In his Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica (1687), Newton also proved mathematical results indicating that a vortex could not possibly generate elliptical motion. – Descartes’ theory was thereby discredited. 39 Gravitation and Intelligibility Newtonian gravity acts at a distance with no intermediate mechanical connexion. – But this is deeply “unintelligible”. – Descartes had objected to the idea of gravity as “occult”: one body would have to “know” where the other was to move towards it. – Many Newtonians took the operation of gravity to be proof of divine action, a new resource against Hobbist materialism. – Newton took a more instrumentalist attitude. 40 Newton’s Methodological Instrumentalism Newton’s public response to the objection: “Hypotheses non fingo” – “I feign no hypotheses”: there’s no obligation to invent speculations about how gravity operates (at least until more evidence comes to light giving a basis for more than mere hypothesis). – If the gravitational equations (etc.) correctly describe the observed behaviour of objects, then that theory should be accepted whatever the unperceived underlying reality might be. 41 John Locke Established “British Empiricist” tradition; Hugely influential also in political philosophy; Christ Church, 1652-84; Essay concerning Human Understanding and Two Treatises of Government, 1690. 42 Locke and Corpuscularianism Locke’s Essay took Boyle’s “corpuscularian hypothesis” as the best available: – Boyle’s “universal matter” becomes “substance in general”; “impenetrability” becomes “solidity”. – Underlying substance has primary qualities: shape, size, movement etc., texture, solidity. – Secondary qualities (e.g. colour, smell, taste) are powers to cause ideas in us. – Primary qualities in objects resemble our ideas of them; secondary qualities do not. 43 Empiricism and Essences Locke is empiricist, and modest … 44 – All our ideas are derived from experience, so we can’t rely on Cartesian “innate ideas”. – (Virtually) all knowledge of the world comes from experience, and hence must be tentative. – We presume a “real essence”: an underlying structure giving rise to the observed properties of substances, and their similarity. – However we have to make do with relying on “nominal essence”: the observable properties by which we identify and sort things. Locke’s Probabilism Reason is a perceptual faculty: rational argument involves perceiving truths and inferential connexions. – Demonstration is when a sequence of intuitive connexions leads from premise to conclusion. But reason does not operate only through logical demonstration, yielding certainty: – Reason can also perceive probable connexions, which can be sequenced together to generate probable reasoning. 45 Locke’s Rationalism Despite his epistemological modesty, Locke seems committed to an ideal of intelligibility: – “if we could discover the … Texture [etc.] … of the minute Constituent parts of … Bodies, we should know without Trial several of their Operations …” (Essay IV iii 25) – The existence of God is provable with certainty, since “it is as impossible that incogitative Matter should produce a cogitative Being, as that nothing … should produce … Matter.” (IV x 11) 46 Thinking Matter and Inertness But Locke speculated that God could, if he wished, “superadd” thought to matter. – Provoked great hostility, opponents arguing that thought is an “active” power, requiring an immaterial soul rather than brute matter. – Matter only has primary qualities and what directly flows from them. – Matter is clearly “passive” or “inert”, as indicated by phenomenon of inertia. – If matter could think, what of immortality? 47 Locke on Personal Identity Agnosticism about substances gave Locke a particular problem with personal identity. – Our experience gives us no insight into the nature of mental “substance”, only its activity. – Analogy with plants suggests an organism’s identity is not tied to its constituent substance. – The notion of personal identity is “forensic”: vital in issues of morality and responsibility. Locke attempts to ground this vital notion in consciousness and memory. 48 The Powers of Matter Most were deeply unhappy with a view of man that was compatible with materialism, which they saw as atheistical and mortalist. Again, their main argument was that matter is passive and inert, so it cannot perceive or think (Descartes, Cudworth etc.), or attract gravitationally (various Newtonians); hence there must be a non-material substance with these effects. Occasionalism and Immaterialism pushed this line of thought much further … 49 Nicolas Malebranche The leading Cartesian of the late 17th century. Often now ignored, but influential in England as well as his native France. Built on the claim of matter’s inertness, developing the theory of occasionalism. Though considered a “rationalist”, he was a major influence on the “empiricist” Berkeley. 50 Malebranche and Causation Matter is inert, and has no causal impact on the world; the only cause is God. – A real cause must necessitate its effect, but we can conceive any physical “cause” occurring without its “effect”, so it can’t be a real cause. – Only the will of an omnipotent Being can truly necessitate an effect in this sense. – God sustains the world, in effect re-creating it from moment to moment (as Descartes taught), hence again He brings everything about. 51 Malebranche’s Occasionalism Malebranche’s theory implies that physical objects are not real causes. – Instead they are “occasional” causes: when one billiard ball hits another, this provides the occasion for God to cause the second to move (by re-creating it in a sequence of positions). – God also creates the visual perceptions in our mind corresponding to this physical reality. – But then why not do away with the physical reality entirely, as it seems to play no role? 52 George Berkeley Irish Anglican, 1685-1753, buried in Christ Church. “British empiricist”, but closer to Malebranche than to either Locke or Hume. Immaterialism: the only things that exist are (active) spirits and (passive) “ideas”. God orchestrates our ideas, so objects in the world appear in an orderly fashion. 53 Berkeley’s Immaterialism Berkeley’s immaterialism is essentially occasionalism without the material world. But he uses a different set of arguments, appealing to perception and meaningempiricism rather than to metaphysics: – Combines Lockean principle that only ideas are immediately perceived, with plain man’s belief that trees etc. are immediately perceived; – Denies intelligibility of perceived objects (or anything resembling them) existing unperceived. 54 Perception According to Locke Idea in the mind Material object (directly perceived) (cause of the idea) The “Veil of perception” problem: how can we know whether there is a real material object? 55 Perception According to Berkeley Idea in the mind = the tree (directly perceived; caused by God) No veil of perception problem, because what we directly perceive (i.e. the idea) is the tree. 56 Berkeley on Primary and Secondary Qualities We can be mistaken about PQs just as we can about SQs: they too are in the mind. All ideas are derived from experience, hence our ideas of PQs (e.g. shape) are infused with those of the sensory SQs by which we perceive them (e.g. a colour that fills the space). PQs without SQs are inconceivable. We cannot make any sense of something non-mental resembling an idea. 57 Berkeley’s Instrumentalism Immaterialism might seem to undermine physical science, but Berkeley (following Newton) advocated instrumentalism: – The aim of science is to discover “laws” that generate true predictions about phenomena. – It is irrelevant whether the theoretical entities (e.g. forces) invoked have any real existence. – God benevolently arranges the observed phenomena to follow these patterns, as “signs” to enable us to direct our lives. 58 David Hume, The Great Infidel Scottish, 1711-76 Treatise of Human Nature 1739 Essays (various) 1741Enquiries concerning Human Understanding 1748, and Principles of Morals 1751 Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion 1779 59 Building on Newton and Locke Newtonianism – Newton provides a model of good science, modestly aiming “to reduce the principles, productive of natural phenomena, to a greater simplicity, and to resolve the many particular effects into a few general causes”. (E 4.12) Probabilism – Locke is right to emphasise probability rather than demonstration as the basis for our discovery of truths about the world. BUT … 60 Hume on Mechanical Causation Suppose we see a white billiard ball moving towards a red one and colliding with it. Why do we expect the red one to move? Imagine Adam, newly created by God, trying to envisage what would happen: how could be possibly have any idea at all in advance of experience? The “intelligibility” of mechanical causation is just an illusion, engendered by familiarity. 61 Science and Intelligibility Methodological Instrumentalism – All causation is “unintelligible”: we don’t really understand why anything causes anything. – Malebranche and Berkeley had the right idea about natural causes: there is no intelligible connexion between cause and effect, so we must view all “natural laws” instrumentally (and not just Newton’s law of gravitation). – But in Hume’s universe there’s no role for God: it’s a sort of atheistic occasionalism! 62 Hume on Induction Does experience of impacting billiard balls give me a good reason for expecting the red ball to move after the collision? If so, I must have a good reason for taking my past experience as a guide to the future. But resemblance of the future to the past isn’t self-evident, and I can’t know it through the senses. Nor can it be proved logically, while appealing to experience to support it would be “begging the question”: arguing in a circle. 63 Humean “Reason” Against Lockean “Rationalistic Probabilism” – Lack of “intelligibility” does not merely imply that our judgements about the world are uncertain; we cannot even claim to have any rational grasp of, or insight into, probable connexions. The Foundation of Induction – Scientific (like all empirical) reasoning is founded not on insight, but on a brute assumption that the future will resemble the past, for which no solid basis can be given. 64 Man’s Place in Nature Not “Made in God’s Image” – Our Reason is a natural faculty (rather than any sort of godlike insight). There’s no basis for thinking of man as supernaturally privileged; instead, he should be viewed as part of the natural world, alongside the beasts. A Subject of Empirical Study – The human world, like the natural world, can be known only through observation, experiment, systematisation and generalisation. 65 Hume on Free Will Hume, like Hobbes, is a compatibilist, seeing moral freedom as compatible with determinism. Human actions are necessary in the same sense as material interactions (indeed we can only understand necessity in one way, based on our own habits of prediction). Free will is simply having the power to act as our will dictates. This doesn’t undermine moral responsibility because morality is based on sentiment. 66 The Elephant in the Room Theological concerns underlie most philosophy over this period. In the Medieval picture, things operate through “natures” and purposes laid down by God. Moving from an Aristotelian to a mechanical model of nature removes the purposes, and threatens an atheistic universe. Religious disagreement also undermines appeal to traditional authority – encouraging a search for something to take its place. 67 A (Very Simplistic) “Big Picture” Medieval Early Modern 68 Physics Morals Politics Governed by natural motions Revealed truth and natural law King is divinely ordained Inert matter, Revelation? Natural right? mechanical Reason? Reason? causation, Moral sense? Contract? forces Feeling? Raw power? In the Wake of Mechanistic Science The world differs radically from how it appears: our best theory attributes primary qualities to bodies, with secondary qualities explained through a representative theory of perception. This invites scepticism: if we can’t trust our natural faculties to yield truth directly, then how can we know what things are really like? If the actions of body are explained mechanically, then how can mind fit in? The relation between them seems completely mysterious. 69 Moreover a completely mechanical account of the actions of body implies that our behaviour is determined. What then of free will, and how can divine punishment be justified? Reward or punishment relies on the premise of personal identity over time, and the afterlife requires this to withstand bodily dissolution. How can we make sense of this, so as to safeguard both religion and morality? If Hume is right, we can’t. And our attempts to make sense of the world are anyway doomed by the limits of our faculties, as shown by our inability to justify even basic induction. 70 Immanuel Kant (1783) Hume has to be wrong, because we have clear examples of “synthetic a priori” knowledge: truths about the world knowable independently of experience, that we see had to be that way: 71 – Metaphysical principles (e.g. universal causation) – Euclidean geometry (e.g. Pythagoras’ theorem) – Newtonian mechanics (e.g. conservation of momentum). Hume’s Triumph! Darwin’s On the Origin of Species (1859) – We are evolved from animals, part of nature. Einstein’s General Relativity (1915) – Space is gravitationally “curved”. – So Euclid’s axioms probably aren’t true, and they’re certainly not knowable a priori. Quantum Mechanics (1925) 72 – Fundamental particles don’t work at all as we (or Newton) would have expected: their behaviour is describable, but not “intelligible”. A Note from our Sponsors … The Introduction to my Oxford World’s Classics edition of Hume’s Enquiry gives more detail on all of this, together with reference material summarising philosophers’ views etc. All profits to Oxford University Press, which is a department of the University! 73 A Note from our Sponsors … The Introduction to my Oxford World’s Classics edition of Hume’s Enquiry gives more detail on all of this, together with reference material summarising philosophers’ views etc. All profits to Oxford University Press, which is a department of the University! 74 A Note from our Sponsors … The Introduction to my Oxford World’s Classics edition of Hume’s Enquiry gives more detail on all of this, together with reference material summarising philosophers’ views etc. All profits to Oxford University Press, which is a department of the University! 75