Beyond Slavery, for Journal Of Southern History

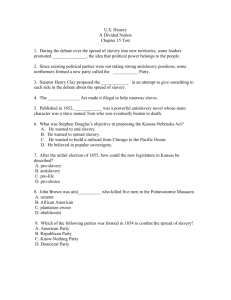

advertisement